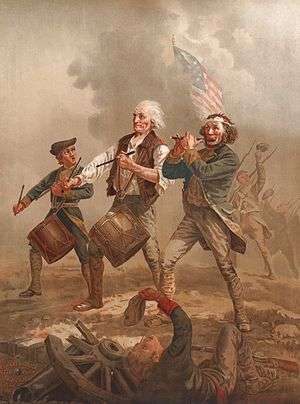

Patriot (American Revolution)

Patriots (also known as Revolutionaries, Continentals, Rebels, or American Whigs) were those colonists of the Thirteen Colonies who rebelled against British control during the American Revolution and in July 1776 declared the United States of America an independent nation. Their rebellion was based on the political philosophy of republicanism, as expressed by spokesmen such as Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and Thomas Paine. They were opposed by the Loyalists who instead supported continued British rule.

As a group, Patriots represented a wide array of social, economic and ethnic backgrounds. They included lawyers like John Adams and Alexander Hamilton; planters like Thomas Jefferson and George Mason; merchants like Alexander McDougall and John Hancock; and ordinary farmers like Daniel Shays and Joseph Plumb Martin. Patriots also included slaves and freemen such as Crispus Attucks, a free man and the first martyr of the American Revolution, James Armistead Lafayette, who served as a double agent for the Continental Army, and Jack Sisson, who under the command of Colonel William Barton, was leader of the first successful black operation mission in American history, resulting in the capture of British General Richard Prescott.

Terms

The critics of British rule called themselves Whigs after 1768, identifying with members of the British Whig party (including the Radical Whigs and Patriot Whigs), who favored similar colonial policies. The Oxford English Dictionary third definition of "Patriot" is "A person actively opposing enemy forces occupying his or her country; a member of a resistance movement, a freedom fighter. Originally used of those who opposed and fought the British in the American War of Independence." The earliest citation is a 1773 letter by Benjamin Franklin. In Britain at the time, "patriot" had a negative connotation, and was used, says Samuel Johnson as a negative epithet for "a factious disturber of the government."[1]

Prior to the Revolution, colonists who supported British authority called themselves Tories or royalists, identifying with the political philosophy then dominant in Great Britain, Traditionalist conservatism. During the Revolution these persons became known primarily as Loyalists. Afterward, many emigrated north to the remaining British territories in what is now modern Canada. There they called themselves the United Empire Loyalists.

Influence

Many Patriots were active before 1775 in groups such as the Sons of Liberty. The most prominent leaders of the Patriots are referred to today by Americans as the Founding Fathers. The Patriots came from many different backgrounds. Among the most active of the Patriots group were highly educated and fairly wealthy individuals. However, without the support of the ordinary men and women, such as farmers, lawyers, merchants, seamstresses, homemakers, shopkeepers, and ministers, the struggle for independence would have failed.

Historian Robert Calhoon said the consensus of historians is that between 40 and 45 percent of the white population in the Thirteen Colonies supported the Patriots' cause, between 15 and 20% supported the Loyalists, and the remainder were neutral or kept a low profile.[2] With a white population of about 2.5 million, that makes about 380,000 to 500,000 Loyalists. The great majority of them remained in America, since only about 80,000 Loyalists left the United States 1775–1783. They went to Canada, Britain, Florida or the West Indies, but some eventually returned.[3]

Motivations

To understand how people made the choice between being a Patriot or a Loyalist, historians have compared the motivations and personalities of leading men on each side. Labaree (1948) has identified eight characteristics that differentiated the two groups. Psychologically, Loyalists were older, better established, and more likely to resist innovation than the Patriots. Loyalists said the Crown was the legitimate government and resistance to it was morally wrong, while the Patriots thought morality was on their side because the British government had violated the constitutional rights of Englishmen. Men who were alienated by physical attacks on Royal officials took the Loyalist position, while those who applauded were being Patriots. Most men who wanted to find a compromise solution wound up on the Loyalist side, while the proponents of immediate action became Patriots. Merchants in the port cities with long-standing financial and sentimental attachments to the Empire were likely to remain loyal to the system, while few Patriots were so deeply enmeshed in the system. Some Loyalists were procrastinators who believed that independence was bound to come some day, but wanted to postpone the moment; the Patriots wanted to seize the moment. Loyalists were cautious and afraid of anarchy or tyranny that might come from mob rule; Patriots made a systematic effort to use and control mob violence. Finally, Labaree argues that Loyalists were pessimists who lacked the Patriots' confidence that independence lay ahead.[4][5][6]

No taxation without representation

The Patriot faction came to reject taxes imposed by legislatures in which the tax-payer was not represented. "No taxation without representation," was their slogan, referring to the lack of representation in the British Parliament. The British countered there was "virtual representation," that is, all members of Parliament represented the interests of all the citizens of the British Empire.

Though some Patriots declared that they were loyal to the king, they believed that the assemblies should control policy relating to the colonies. They should be able to run their own affairs. In fact, they had been running their own affairs since the period of "salutary neglect" before the French and Indian War. Some radical Patriots tarred and feathered tax collectors and customs officers, making those positions dangerous; the practice was especially prevalent in Boston, where many Patriots lived, but was curbed there sooner than elsewhere.[7]

List of prominent Patriots

Most of the individuals listed below served the American Revolution in multiple capacities.

Statesmen and office holders

- Thomas Jefferson

- John Adams

- John Hancock

- John Dickinson

- Benjamin Franklin

- Jonathan Shipley

- William Paca

- James Madison

Pamphleteers and activists

- Samuel Adams

- Alexander Hamilton

- William Molineux

- Timothy Matlack

- Thomas Paine

- Paul Revere

- Patrick Henry

- Samuel Prescott

- Molly Pitcher

- Roger Sherman

- Philip Mazzei

- Elkanah Watson

Military officers

- Nathanael Greene

- Nathan Hale

- Francis Marion

- Andrew Pickens

- Daniel Morgan

- James Mitchell Varnum

- Joseph Bradley Varnum

- George Washington

- John Paul Jones

- Thomas Sumter

- Francis Vigo

- Elijah Isaacs

- Benedict Arnold (defected)

Black Patriots

- Crispus Attucks

- Jack Sisson

- James Armistead Lafayette

- 1st Rhode Island Regiment

- William Flora

- Saul Matthews

- Prince Whipple

Native American Patriots

Also see

- American Loyalists

References

- ↑ "Patriot" in Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed. online 2011). accessed 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Robert M. Calhoon, "Loyalism and neutrality" in Jack P. Greene; J. R. Pole (2008). A Companion to the American Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. p. 235.

- ↑ Thomas B. Allen, Tories: Fighting for the King in America's First Civil War (2011) p. xviii

- ↑ Leonard Woods Larabee, Conservatism in Early American History (1948) pp. 164–65

- ↑ See also N. E. H. Hull,Peter C. Hoffer and Steven L. Allen, "Choosing Sides: A Quantitative Study of the Personality Determinants of Loyalist and Revolutionary Political Affiliation in New York," Journal of American History, Vol. 65, No. 2 (Sept. 1978), pp. 344–66 in JSTOR

- ↑ The most in-depth study of the Patriot psychology is Edwin G. Burrows and Michael Wallace, "The American Revolution: The Ideology and Psychology of National Liberation," Perspectives in American History, (1972) vol. 6 pp. 167–306

- ↑ Benjamin H. Irvin, "Tar and Feathers in Revolutionary America," (2003)

Bibliography

- Ellis, Joseph J. . Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (2002), Pulitzer Prize

- Kann, Mark E.; The Gendering of American Politics: Founding Mothers, Founding Fathers, and Political Patriarchy, (1999) online version

- Middlekauff, Robert; The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (2005) online version

- Miller, John C. Origins of the American Revolution. (1943) online version

- Miller, John C. Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783, (1948) online version

- Previdi, Robert; "Vindicating the Founders: Race, Sex, Class, and Justice in the Origins of America," Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 29, 1999

- Rakove, Jack. Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America (2010) excerpt and text search

- Raphael, Ray. A People's History of the American Revolution: How Common People Shaped the Fight for Independence (2002)

- Roberts, Cokie. Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation (2005)