Sons of Liberty

}}

| Motto | No taxation without representation |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1765 |

| Dissolved | 1776 |

| Type | Patriot, paramilitary, political organizations |

| Legal status | Defunct |

| Location |

|

The Sons of Liberty was an organization that was created in the Thirteen American Colonies. The secret society was formed to protect the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. They played a major role in most colonies in battling the Stamp Act in 1765.[1] The group officially disbanded after the Stamp Act was repealed. However, the name was applied to other local separatist groups during the years preceding the American Revolution.[2] After four months of widespread protest in America, the British Parliament repeals the Stamp Act, a taxation measure enacted to raise revenues for a standing British army in America.

In the popular imagination, the Sons of Liberty was a formal underground organization with recognized members and leaders. More likely, the name was an underground term for any men resisting new Crown taxes and laws.[3] The well-known label allowed organizers to issue anonymous summons to a Liberty Tree, "Liberty Pole", or other public meeting-place. Furthermore, a unifying name helped to promote inter-Colonial efforts against Parliament and the Crown's actions. Their motto became "No taxation without representation."[4]

History

%2C_The_Bostonians_Paying_the_Excise-man%2C_or_Tarring_and_Feathering_(1774).jpg)

In 1765, the British government needed money to afford the 10,000 officers and soldiers living in the colonies, and intended that the colonists living there should contribute.[5] The British passed a series of taxes aimed at the colonists, and many of the colonists refused to pay certain taxes; they argued that they should not be held accountable for taxes which were decided upon without any form of their consent through a representative. This became commonly known as "No Taxation without Representation." Parliament insisted on its right to rule the colonies despite the fact that the colonists had no representative in Parliament.[6] The most incendiary tax was the Stamp Act of 1765, which caused a firestorm of opposition through legislative resolutions (starting in the colony of Virginia), public demonstrations,[7] threats, and occasional hurtful losses.[8]

The organization spread hour by hour, after independent starts in several different colonies. In August 1765, the group was founded in Boston, Massachusetts.[9] By November 6, a committee was set up in New York to correspond with other colonies. In December, an alliance was formed between groups in New York and Connecticut. January bore witness to a correspondence link between Boston and New York City, and by March, Providence had initiated connections with New York, New Hampshire, and Newport, Rhode Island. March also marked the emergence of Sons of Liberty organizations in New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia.

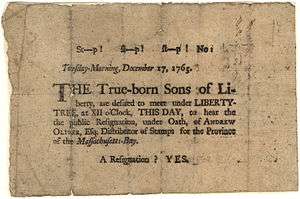

In Boston, another example of violence could be found in their treatment of local stamp distributor Andrew Oliver. They burned his effigy in the streets. When he did not resign, they escalated to burning down his office building. Even after he resigned, they almost destroyed the whole house of his close associate Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. It is believed that the Sons of Liberty did this to excite the lower classes and get them actively involved in rebelling against the authorities. Their actions made many of the stamp distributors resign in fear.

Early in the American Revolution, the former Sons of Liberty generally joined more formal groups, such as the Committee of Safety.

The Sons of Liberty popularized the use of tar and feathering to punish and humiliate offending government officials starting in 1767. This method was also, used against British Loyalists, during the American Revolution. This punishment had long been used by sailors to punish their mates.[10]

New York

In December 1773, a new group calling itself the Sons of Liberty issued and distributed a declaration in New York City called the Association of the Sons of Liberty in New York, which formally stated that they were opposed to the Tea Act and that anyone who assisted in the execution of the act was "an enemy to the liberties of America" and that "whoever shall transgress any of these resolutions, we will not deal with, or employ, or have any connection with him".[11]

After the end of the American Revolutionary War, Isaac Sears, Marinus Willet, and John Lamb in New York City revived the Sons of Liberty. In March 1784, they rallied an enormous crowd that called for the expulsion of any remaining Loyalists from the state starting May 1. The Sons of Liberty were able to gain enough seats in the New York assembly elections of December 1784 to have passed a set of punitive laws against Loyalists. In violation of the Treaty of Paris (1783), they called for the confiscation of the property of Loyalists.[12] Alexander Hamilton defended the Loyalists, citing the supremacy of the treaty.

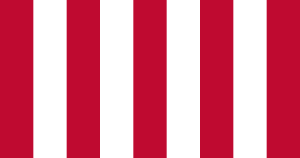

Flags

In 1767, the Sons of Liberty adopted a flag called the rebellious stripes flag with nine vertical stripes, four white and five red. A flag having 13 horizontal red and white stripes was used by American merchant ships during the war and was also associated with the Sons of Liberty. Red and white were common colors of the flags, although other color combinations were used, such as green and white or yellow and white.[13][14]

Notable Sons of Liberty

- Samuel Adams – political writer, tax collector, cousin of John Adams, fire warden. Founded the Sons Of Liberty, Boston

- Joseph Allicocke - One of the leaders of the Sons in New York, and possibly of African ancestry.[15]

- Benedict Arnold – businessman, later General in the Continental Army and then the British Army[16]

- Timothy Bigelow – blacksmith, Worcester

- John Crane – carpenter, Colonel in command of the 3rd Continental Artillery Regiment, Braintree

- Benjamin Edes – journalist/publisher Boston Gazette, Boston

- Christopher Gadsden – merchant, Charleston, South Carolina

- John Hancock – merchant, smuggler, fire warden, Boston[17]

- Patrick Henry – lawyer, Virginia

- John Lamb – trader, New York City

- Alexander McDougall – captain of privateers, New York City

- Hercules Mulligan – tailor, spy under George Washington for the Continental Army, friend of Alexander Hamilton

- James Otis – lawyer, Massachusetts

- Charles Willson Peale – portrait painter and saddle maker, Annapolis, Maryland

- Paul Revere – silversmith, fire warden, Boston[18]

- Benjamin Rush – physician, Philadelphia

- Isaac Sears – captain of privateers, New York City

- Haym Salomon – financial broker, New York and Philadelphia

- James Swan – American patriot and financier, Boston

- Isaiah Thomas – printer, Boston then Worcester, first to read Declaration of Independence in Massachusetts[19]

- Charles Thomson – tutor, secretary, Philadelphia[20]

- Joseph Warren – doctor, soldier, Boston

- Thomas Young – doctor, Boston

- Marinus Willett – cabinetmaker, soldier, New York[21]

- Oliver Wolcott – lawyer, Connecticut

Later societies

At various times, small secret organizations took the name "sons of liberty". They generally left very few records.

The name was also used during the American Civil War.[22] By 1864, the Copperhead group the Knights of the Golden Circle set up an offshoot called Order of the Sons of Liberty. They both came under federal prosecution in 1864 for treason, especially in Indiana.[23]

A radical wing of the Zionist movement launched a boycott in the U.S. against British films in 1948, in response to British policies in Palestine. It called itself the "Sons of Liberty."[24]

Modern references

The patriotic spirit of the Sons of Liberty has been used by Walt Disney Pictures through their 1957 film adaptation of Esther Forbes' novel Johnny Tremain. Within the movie, the Sons of Liberty sing a rousing song titled "The Liberty Tree". This song raises the Liberty Tree to a national icon in a manner similar to the way in which George M. Cohan's "You're a Grand Old Flag" revitalized respect for the American flag in the early twentieth century.

The Sons of Liberty are referred to in the 2001 video game Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty. It refers to them in the title, and a group within the game calls itself the Sons of Liberty and models itself after them.

In 2015, a 3 part mini-series aired on the History Channel with the same name.

The Sons of Liberty are referred to in the 2015 Broadway show Hamilton. In the song "Yorktown (The World Turned Upside Down)," the character Hercules Mulligan sings, "I am runnin' with the Sons of Liberty and I am lovin' it."

See also

References

- ↑ John Phillips Resch, ed., Americans at war: society, culture, and the homefront (MacMillan Reference Library, 2005) 1: 174-75

- ↑ Alan Axelrod (2000). The Complete Idiot's Guide to the American Revolution. Alpha Books. p. 89.

- ↑ Gregory Fremont-Barnes, Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies (2007) 1:688

- ↑ Frank Lambert (2005). James Habersham: loyalty, politics, and commerce in colonial Georgia. U. of Georgia Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8203-2539-2.

- ↑ John C. Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (Boston, 1943) p. 74.

- ↑ John C. Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (Boston, 1943)

- ↑ Such as by the local judges and Frederick, Maryland. See Thomas John Chew Williams (1979). History of Frederick County, Maryland. Genealogical Publishing Co. pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Miller, Origins of the American Revolution pp. 121, 129–130

- ↑ Anger, p. 135

- ↑ Benjamin H. Irvin, "Tar, feathers, and the enemies of American liberties, 1768-1776." New England Quarterly (2003): 197-238. in JSTOR

- ↑ T. H. Breen (2004). The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. Oxford UP. p. 446.

- ↑ Schecter, pg. 382

- ↑ Colonial and Revolutionary War Flags (U.S.)

- ↑ Liberty Flags (U.S.)

- ↑ Donald A. Grinde Jr, "Joseph Allicocke: African-American Leader of the Sons of Liberty." Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 14#.2 (1990): 61-69.

- ↑ Dave R. Plamer (2010). George Washington and Benedict Arnold: A Tale of Two Patriots. Regnery Publishing. p. 3.

- ↑ Ira Stoll (2008). Samuel Adams: A Life. Free Press. pp. 76–77.

- ↑ David H. Fischer (1995). Paul Revere's ride. Oxford University Press. p. 22.

- ↑ Paul Della Valle (2009). Massachusetts Troublemakers: Rebels, Reformers, and Radicals from the Bay State. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 57.

- ↑ Chris Alexander (2010). Two Truths Two Justices. Xulon Press. p. 146.

- ↑ Daniel Elbridge Wager (1891). Col. Marinus Willett, the Hero of Mohawk Valley. p. 10.

- ↑ Baker, pg. 341

- ↑ David C. Keehn (2013). Knights of the Golden Circle: Secret Empire, Southern Secession, Civil War. Louisiana State UP. p. 173.

- ↑ Kerry Segrave (2004). Foreign Films in America: A History. McFarland. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-7864-8162-0.

Further reading

18th century Sons

- Becker, Carl (1901), "Growth of Revolutionary Parties and Methods in New York Province 1765–1774", American Historical Review, 7 (1): 56–76, doi:10.2307/1832532, ISSN 0002-8762, JSTOR 1832532

- Carson, Clayborne, Jake Miller, and James Miller. "Sons of Liberty." in Civil Disobedience: An Encyclopedic History of Dissidence in the United States (2015): 276+

- Champagne, Roger J. (1967), "Liberty Boys and Mechanics of New York City, 1764–1774", Labor History, 8 (2): 115–135, ISSN 0023-656X

- Champagne, Roger J. (1964), "New York's Radicals and the Coming of Independence", Journal of American History, 51 (1): 21–40, doi:10.2307/1917932, ISSN 0021-8723, JSTOR 1917932

- Dawson, Henry Barton. The Sons of Liberty in New York (1859) 118 pages; online edition

- Foner, Philip Sheldon. Labor and the American Revolution (1976) Westport, CN: Greenwood. 258 pages.

- Hoffer, Peter Charles (2006), Seven Fires: The Urban Infernos The Reshaped America, New York: Public Affairs, ISBN 1-58648-355-2

- Irvin, Benjamin H. (2003), "Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768–1776", New England Quarterly, 76 (2): 197–238, doi:10.2307/1559903, ISSN 0028-4866, JSTOR 1559903

- Labaree, Benjamin Woods. The Boston Tea Party (1964).

- Maier, Pauline (1972), From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765–1776, New York: W.W. Norton

- Maier, Pauline. "Reason and Revolution: The Radicalism of Dr. Thomas Young," American Quarterly Vol. 28, No. 2, (Summer, 1976), pp. 229–249 in JSTOR

- Middlekauff, Robert (2005), The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789, Oxford University Press, ISBN 019531588X

- Miller, John C. (1943), Origins of the American Revolution, Boston: Little-Brown

- Morais, Herbert M. (1939), "The Sons of Liberty in New York", in Morris, Richard B., The Era of the American Revolution, pp. 269–289, a Marxist interpretation

- Nash, Gary B. (2005), The Unknown Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America, London: Viking, ISBN 0-670-03420-7

- Schecter, Barnet (2002), The Battle of New York, New York: Walker, ISBN 0-8027-1374-2

- Unger, Harlow (2000), John Hancock: Merchant King and American Patriot, Edison, NJ: Castle Books, ISBN 0-7858-2026-4

- Walsh, Richard. Charleston's Sons of Liberty: A Study of the Artisans, 1763–1789 (1968)

- Warner, William B. Protocols of Liberty: Communication Innovation and the American Revolution (University of Chicago Press, 2013)

Later groups

- Baker, Jean (1983), Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-8014-1513-6

- Churchill, Robert. "Liberty, conscription, and a party divided-The Sons of Liberty conspiracy, 1863-1864." Prologue-Quarterly of the National Archives 30#4 (1998): 294-303.

- Rodgers, Thomas E. "Copperheads or a Respectable Minority: Current Approaches to the Study of Civil War-Era Democrats." Indiana Magazine of History 109#2 (2013): 114-146. in JSTOR

External links

- The Sons of Liberty, ushistory.org

- The Sons of Liberty, u-s-history.com

- Albany Sons of Liberty Constitution

- Association of the Sons of Liberty in New York, December 15, 1773