Timothy Matlack

Timothy Matlack (May 28, 1736 – April 14, 1826) was a brewer and beer bottler who emerged as a popular and powerful leader in the American Revolutionary War. Secretary of Pennsylvania during the war, and a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in 1780, he became one of Pennsylvania's most provocative and influential political figures. Removed from office by his political enemies at the end of the war, he returned to power in the Jeffersonian era.[1]

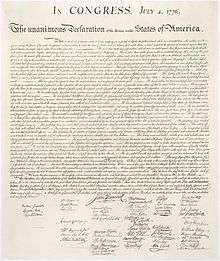

Matlack, who was known for his excellent penmanship, was chosen to write the original United States Declaration of Independence on vellum.[2]

Biography

Timothy Matlack was born in Haddonfield, New Jersey on May 28, 1736, to Elizabeth Martha Burr Haines and Timothy Matlack: a couple that had both lost their first spouses. His grandparents were William Matlack and Mary Hancock; and Henry Burr and Elizabeth Hudson. His siblings were Sybil, Elizabeth, Titus, Seth, Josiah and White Matlack. His half siblings were Reuben and Mary Haines. His first cousin was the Quaker abolitionist John Woolman.[3] In 1738, the family moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where Timothy attended Friends' School. He likely studied under Anthony Benezet. In 1749 he was apprenticed to the prosperous Quaker merchant John Reynell. During his period of service Timothy was considered a strong candidate for the Quaker ministry. At the end of his term he married Ellen Yarnall, the daughter of the Quaker minister Mordecai Yarnall. The couple had five children: William, Mordecai, Sibyl, Catharine and Martha.

In 1760 Matlack opened a mercantile he called the Case Knife. Two years later he and Owen Biddle purchased the Petty's Run steel furnace in Trenton, New Jersey. In 1764, following the failure of his shop, Timothy was disowned by the Quakers. The Quakers complained that he had been “frequenting company in such a manner as to spend too much of his time from home.” In 1768, and again in 1769, he was confined to debtors' prison. By this time Timothy Matlack had set up a new business selling bottled beer. In 1769 he opened his own brewery, located near the State House, or Independence Hall. A horse racing enthusiast,in 1770 he pitted his gamecocks against those owned by the New York aristocrat James Delancey in an infamous main.

In 1774 Matlack was hired by Charles Thomson, Secretary of the First Continental Congress, to engross the body's formal address to the King of England. In May, 1775, he became clerk to the Second Continental Congress and in June he composed George Washington's commission as General and Commander-in-Chief of the army of the United Colonies. In October Congress elevated Matlack to Storekeeper of Military Supplies. By this time he was also a member of Philadelphia's Committee of Inspection and Secretary of the Committee of Officers of the city's three militia battalions. By December he was serving as Secretary to Congress's Marine Committee, chaired by John Hancock. By January, 1776, he was Commissary and Clerk-in-Chief of the Committee of Claims. That month Philadelphia added two more battalions to its militia brigade and Timothy Matlack was elected Colonel of the Fifth Battalion of Rifle Rangers. In February he was made an officer of the city's Committee of Inspection and added to a key policy-making subcommittee. On May 20, 1776, Matlack was a principal speaker at a massive town meeting in the State House yard. He was a delegate to the Conference of Committees which met in June to plan for the Convention which would write a new constitution for Pennsylvania. These laws were to form the basis of a new government. That night, Matlack likely attended John Dunlap's print shop, and printed copies of the declaration were ready by morning. Later that month Matlack engrossed the Declaration of Independence on parchment. Members of Congress began signing that historic document on August 2. On July 8, 1776, Colonel John Nixon read Congress's declaration of independence to a crowd gathered at the State House.

As a leader of the Pennsylvania Convention he was instrumental in drafting the ultra-democratic Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776. In the years that followed he was an ardent defender of this frame against such critics as Benjamin Rush, James Wilson and John Dickinson. Newspapers were his primary medium and he signed a number of articles with the pseudonym Tiberius Gracchus.[4] Critics responded with the sobriquet 'Tim Gaff.' As Secretary to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, Matlack was one of the most powerful men in the new state during the war years. In 1780 his government passed an Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, the first law of its kind in the Western Hemisphere.

On December 27, 1776, following Washington's victory at Trenton, the Philadelphia and Pennsylvania militia crossed the Delaware River and camped at Burlington. Colonel Timothy Matlack and his 5th Rifle Battalion were part of this expedition. On January 2, they were involved in the Battle of Assumpink Creek, the second battle of Trenton. On January 3 the militia fought bravely at the Battle of Princeton. Matlack's force continued to serve in this winter campaign until it dissolved at the end of the month. General Washington credited the Pennsylvania militia for their timely service in this campaign. Other officers commended the Philadelphia force for its manliness and spirit.

Following the British occupation of Philadelphia General Washington assigned Major General Benedict Arnold to the post of Commandant of Philadelphia. Secretary Matlack learned to despise the man's presence. Matlack led an investigation of his wrongdoing which triggered a court martial. The court sentenced Arnold to be severely reprimanded by the Commander-in-Chief. Washington said his officer's behavior had been "reprehensible." Five months later Arnold's treason at West Point was discovered.

In this period, at the height of his power, Matlack was named a trustee (1779–1785) of the new University of the State of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pennsylvania). He was also a Secretary of the American Philosophical Society. In 1780, Matlack delivered an address before the Society in which he advocated the institutionalization of agricultural in the interest of national development. “In our endeavors to promote the interest and happiness of our country,” Matlack declared, “let us apply to intelligent husbandmen in every part of the state and collect the real knowledge among us" and "arrange it into science”. Matlack called upon the University of the State of Pennsylvania, as well as other colleges, to foster the development of modern agricultural research and education in America. "The Star-bespangled Genius of America..." he proclaimed, "points to Agriculture as the stable Foundation of the rising mighty Empire."[5]

In 1781, Matlack was among the founders of the Religious Society of Free Quakers, which consisted mostly of Quakers disowned for their support of or participation in the armed conflict with Great Britain during the American war for independence. One of the earliest opponents of slavery in British colonies in America, Matlack felt the Quakers were not moving quickly enough on abolition. Along with Benjamin Franklin, Robert Morris and others, Matlack helped raise a substantial sum of money to construct the Free Quaker Meeting House at the corner of Fifth and Arch streets in downtown Philadelphia, where he and other members of the society, including his brothers Josiah and White, openly worshiped.[6] Matlack has been attributed with the architectural design of the Free Quaker Meeting House and its masonry vaults. He was also hired in 1794 by Philadelphia merchant and politician Anthony Morris to design a late Georgian style mansion in the countryside just outside Philadelphia. The estate is known today as the Highlands.

In 1790, Matlack was commissioned along with Samuel Maclay and John Adlum by the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania to survey the "headwaters of the Susquehanna River and the streams of the New Purchase," the northwestern portion of the state purchased from the American Indians. They were also charged with exploring a route for a passageway to connect the West Branch with the Allegheny River.[7]

Matlack lived at a home, located at present-day 220-222 East Orange Street, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, from 1799 until 1808 during the years that the city of Lancaster was the state capital of Pennsylvania.[2] He worked as a clerk of the Pennsylvania State Senate while residing in the city.[2] He was known for his household garden, which included "28 types of peach trees."[2]

After his death in Holmesburg, Pennsylvania on April 14, 1826, Matlack was interred in the Free Quaker Burial Ground on South Fifth Street, Philadelphia. His remains were removed from the Burial Ground in 1905 and reinterred in the Wetherill Cemetery in the current village of Audubon, Matson's Ford, Montgomery Co., Pennsylvania, in the Flatlands of the Schuylkill River opposite Valley Forge.

Penmanship

Handwriting in the colonial period was heavily influenced by Europe, in particular by 18th century English writing masters. By the mid-18th century, there were special schools established to teach handwriting techniques, or penmanship.

Master penmen like Timothy Matlack were employed to copy official documents such as land deeds, birth and marriage certificates, military commissions, and other legal documents. The development of copperplate engraving allowed for the use of very delicate type faces with many flourishes and curlicues in the script-like letters, which greatly influenced handwriting. Elegant handwriting became a sign of social status. One can readily see these influences in Matlack's penmanship in the Declaration of Independence. In particular, his use of English Roundhand script stands out. This form of script was executed with a feather quill pen and was actually a form of handwriting. The script is known today as Copperplate.

Matlack's penmanship in the Declaration and other historical documents of the time has inspired a number of modern typefaces, or fonts, such as American Scribe, Declaration Script, Declaration Blackletter, and National Archive.

In popular culture

- Timothy Matlack is mentioned in a riddle in the movie National Treasure.

Notes

- Coelho, Chris. Timothy Matlack: Scribe of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013.

- Fanelli, Doris Devine, Karie Diethorn and John C. Milley. History of the Portrait Collection, Independence National Historical Park. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2001.

- Johnson, Allen and Dumas Malone, eds. Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner & Sons, 1933, vol 12, pp 409–410

- Landis, Bertha Cochran. Col. Timothy Matlack. Papers read before the Lancaster County Historical Society, Vol. XLII-No.6; Lancaster, PA: 1938.

- Stackhouse, A. M. Col. Timothy Matlack, Patriot and Soldier. [N.p.]: Privately printed, 1910.

- Wetherill, Charles. History of The Religious Society of Friends Called by Some The Free Quakers, in the City of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Printed for the Society, 1894

- Yarnall, John K. Yarnall Family Record in America from 1683 to 1913. Chicago, Dec. 1913.; William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, Vol. II - Philadelphia MM records.

References

- ↑ Coelho, Chris. Timothy Matlack: Scribe of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 Brubaker, Jack (2016-06-28). "The Scribbler: The man who really wrote the Declaration of Independence". (LNP) Lancaster Online. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- ↑ Coelho, Chris Timothy Matlack: Scribe of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013, p.185.

- ↑ Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth, (ed. Millegrand Pencak, W., the Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, PA, 2002, p. 117)

- ↑ Matlack, Timothy. An Oration, delivered March 16, 1780 : Before the Patron, Vice-presidents and Members of the American Philosophical Society, Held at Philadelphia, for Promoting Useful Knowledge. Philadelphia: Styner and Cist, 1780.

- ↑ Peterson, Charles E. Notes on The Free Quaker Meeting House. Washington D.C.: Ross & Perry Inc, 2002.

- ↑ Storey, Henry Wilson. "History of Cambria County, Pennsylvania." New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1907.

External links

- Biography, Timothy Matlack at the University of Pennsylvania

- Free Quaker Meeting House architectural drawing by Timothy Matlack, Library of Congress