Aminuis

| Aminuis | |

|---|---|

| Settlement | |

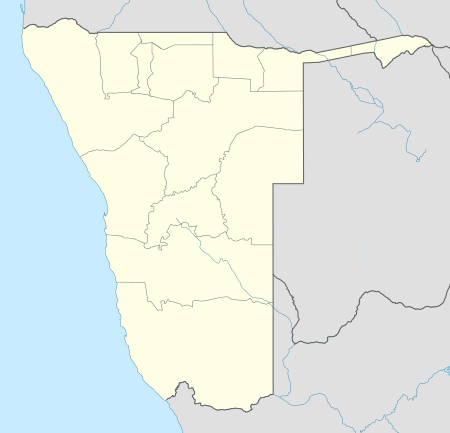

Aminuis Location in Namibia | |

| Coordinates: 23°38′00″S 19°22′00″E / 23.63333°S 19.36667°ECoordinates: 23°38′00″S 19°22′00″E / 23.63333°S 19.36667°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Omaheke Region |

| Constituency | Aminuis Constituency |

| Time zone | South African Standard Time (UTC+1) |

| Climate | BWh |

Aminuis is a cluster of small settlements in the remote eastern part of the Omaheke Region of Namibia, located about 500 km east of Windhoek.[1] It is the district capital of the Aminuis electoral constituency.

Economy and Infrastructure

The village is riddled by poverty and joblessness. The main economic activity is subsistence farming with cattle, goats and sheep but frequent droughts make this difficult. The Tswana people used to mine salt from a nearby pan but went out of business after they could not meet the demand that it be iodised.[1]

There is no post office at Aminuis, and the nearest police station is at Corridor 13. Only the Ministries of Agriculture, Basic Education and Health run small satellite offices.[1] The Catholic Church operates a parish, Our Lady of Perpetual Succour in Aminuis; it belongs to the Archdiocese of Windhoek.[2]

Education

There are a number of schools in the Aminuis area:

- Roman Catholic Mokaleng Combined School, the school first founded by the missionaries in 1902[1]

- Rietquelle Junior Secondary School at Rietquelle,[3] founded in 1935 as first government school for the indigenous population.[4] Founder and at first sole teacher at the school was Otto Schimming.[5]

- Motsomi Primary School[6]

- Hosea Kutako Primary School, built in 1974 with a capacity of 900 learners[6]

History

The area around Aminuis was inhabited by San since at least the 18th century. In the 1880s Tswana people settled at Aminuis with the permission of Andreas Lambert of Leonardville, Kaptein of the Kaiǀkhauan (Khauas Nama).[7]

In 1902 the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a congregation of the Roman Catholic Church, founded a missionary station[8] and a school.[1]

On 1 December 1905 at the height of the Herero and Namaqua War of 1904–1907, Imperial Germany's Schutztruppe ("protection force", the unit deployed to the German colony) and fighters of the Red Nation clashed south-east of Aminuis in the Battle of ǃGu-ǃoms. Manasse ǃNoreseb, leader of the Red Nation and today regarded a hero of the struggle against colonisation in Namibia, died in this battle.[9]

The Herero and Namaqua War of 1904–1907 saw tens of thousands of Herero killed, almost its entire population.[10] Survivors had lost their land and cattle, and the land originally in the hands of the Herero was now farmland in the possession of white settlers. When after World War I Germany lost all its colonies and South-West Africa became mandate territory of South Africa, the new administration was unable, perhaps unwilling, to undo the land transfer.[11]

A South African administrator writes:

"Seeing that the whole Hereroland was confiscated by the Germans and cut up into farms and is now settled by Europeans it would be an impossible project ... to place them back on their tribal lands."[11]

To accommodate the Ovaherero, the South African administration created eight "native reserves" for them of which the Aminuis Reserve was one.[11] After the Aminuis Reserve was declared in the 1920s, landless Herero people migrated into the area and soon formed the vast majority of its inhabitants.[12] The administrative structures of the reserves existed until the 1970s.

When the apartheid government of South Africa devised the Odendaal Plan in the 1960s, part of Aminuis was designated to belong to Tswanaland, a bantustan intended to be a self-governing homeland for the Tswana people. Unlike all other homelands, it was never implemented that way. The Ovaherero were allowed to stay in the area, and the Tswana remained a minority.[13] Tswanaland nevertheless got an ethnic Tswana, Constance Kgosiemang, as political leader between 1980 and 1989.[14]

People

The area of Aminuis today is inhabited by Ovambanderu and a Tswana minority counting approximately 500 people in 2005.[1] Ovambanderu and Herero people share the same ancestry. Herero see the Mbanderu as one of their clans while Mbanderu regard themselves as a distinct group. This difference is the cause of a decades–old rift between the two, with one faction, the Ovambanderu Council of Epukiro and Aminuis seeking recognition of the Mbanderu as a distinct tribe. The other faction aims for a strong and united Herero people under the Tjamuaha-Maharero Royal House and accuses the Mbanderu of artificial division.[15]

Today the Ovambanderu Traditional Authority is the heir of the Ovambanderu Council. Their headquarters is situated at the small settlement of Omauozonjanda which belongs to Epukiro but is 40 km east of its centre.[16] The royal homestead is located at Ezorongondo.[17]

After the death of Mbanderu paramount chief Munjuku Nguvauva II in 2008 the rift in the Ovambanderu community deepened. One faction calling themselves the "Concerned Group" supported Keharanjo Nguvauva as successor to the throne. They crowned him in 2008 because he was born in wedlock of Munjuku and his wife Aletta. The other faction of the Ovambanderu Traditional Authority favoured his older half-brother, Deputy Minister of Fisheries Kilus Nguvauva. A government enquiry commission confirmed Keharanjo as chief in 2009.[16]

Notable people from Aminuis

- Constance Kgosiemang, leader of Tswanaland between 1980 and 1989 and member of Namibia's Constituent Assembly[18]

- Steve Mogotsi, politician, the first ethnic Tswana to serve in any Namibian cabinet

- Kuaima Riruako (1935–2014), politician, paramount chief of the Herero and president of the National Unity Democratic Organisation (NUDO)

- Hulda Shipanga, first black nurse in Namibia to be promoted to matron, the highest rank

- Razundara Tjikuzu, former professional footballer who played for Werder Bremen and various other clubs in Bundesliga

- Ebson Uanguta, deputy governor of the Bank of Namibia[19]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tomanga, Gustaf (2 March 2005). "The Folk of Aminuis - A Forgotten People?". New Era. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ "Parishes, Archdiocese of Windhoek". Roman Catholic Church. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Kangueehi, Kuvee (10 January 2007). "Aminuis Tackles Poor Grades". New Era. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Dierks, Klaus. "Chronology of Namibian History, 1935". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Otto Schimming: A self-made man (1908 to 2005) New Era, 22 October 2010

- 1 2 Kangueehi, Kuvee (9 August 2006). "Aminuis Residents Raise Complaints". New Era. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Boden, Gertrud (2008). ǃQamtee Aa Xanya: 'the Book of Traditions' : Histories, Texts and Illustrations from the ǃXoon and 'Nohan People of Namibia. Basler Afrika Bibliographien. pp. 12–13. ISBN 9783905758047.

- ↑ "Oblates of Mary Immaculate. 100 years in Namibia. 1896-2005". Roman Catholic Church Namibia. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ↑ Shiremo, Shampapi (28 October 2011). "Kaptein Manasse !Noreseb: The political strategist and gallant freedom fighter against German colonialism". New Era.

- ↑ UN Whitaker Report on Genocide, 1985, paragraphs 14 to 24, pages 5 to 10 Prevent Genocide International

- 1 2 3 Dierks, Klaus. "Chronology of Namibian History, 1919". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Witte, Marc (1997). "Ökologische Bedingungen der kleinbäuerlichen Landwirtschaft in semiariden Gebieten Namibias und das Fallbeispiel Omaheke" [Ecological conditions of small farmers in semi-arid regions of Namibia, and the case study of Omaheke.] (in German). University of Osnabrück via www.marcwitte.de. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, Entry for Clemens Kapuuo". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, Entry for Constance Kgosimang". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ Dierks, Klaus. "Chronology of Namibian History, 1960". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- 1 2 Weidlich, Brigitte (21 June 2010). "Rift between Mbanderu factions deepens". The Namibian.

- ↑ Weidlich, Brigitte (23 December 2008). "Police instruct Chief not to hold Ezorongondo meeting". The Namibian.

- ↑ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, Entry for Constance Kgosimang". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ Nyaunwa, Nyasha Francis (16 December 2011). "The rise and rise of Uanguta". Namibia Economist.