Antelope Hills expedition

| Antelope Hills Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars, Texas-Indian Wars, Apache Wars | |||||||

Comanches of West Texas in war regalia. Painting by Lino Sánchez y Tapia, circa 1830s | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Tonkawa Anadarko Shawnee |

Comanche Kiowa Apache | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Placido |

Iron Jacket† Peta Nocona | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~220 | 200–600 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~50 killed or wounded |

76 killed 16 captured | ||||||

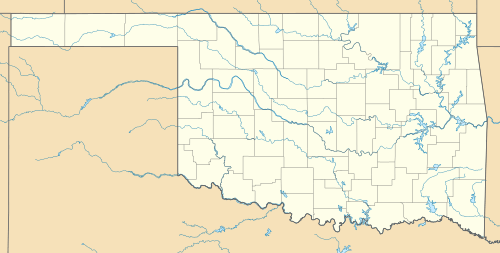

Antelope Hills Expedition Area Location within Oklahoma | |||||||

The Antelope Hills expedition was a campaign from January-May 1858 by the Texas Rangers and members of other allied Native American tribes against Comanche and Kiowa villages in the Comancheria. It began in western Texas and ended in a series of fights with the Comanche tribe on May 12, 1858, at a place called Antelope Hills by Little Robe Creek, a tributary of the Canadian River in what is now Oklahoma. The hills are also called the "South Canadians," as they surround the Canadian River. The fighting on May 12, 1858, is often called the Battle of Little Robe Creek.

Background

Reasons for the expedition

The years 1856-58 on the Texas frontier were particularly vicious and bloody as settlers continued to encroach into the Comancheria. They plowed under valuable hunting grounds, and the Comanche lost grazing land for their herds of horses.[1] In addition, the United States had done a great deal to block the Comanches' traditional raids into Mexico. Finally, the Comanches struck back with a series of ferocious and bloody raids against the settlers.[2]

The Army proved wholly unable to stem the violence. Not only were units being transferred, but federal law and numerous treaties barred the Army from attacking Indians in the Indian Territories. Although many Indians, such as the Cherokee, were trying to farm and live as settlers, the Comanche and Kiowa continued to live in that part of the Indian Territories which was traditionally the Comancheria, while raiding into Texas.[3]

As the American Civil War drew closer, federal forces were moved about even more and the 2nd Cavalry was transferred from Texas to Utah (eventually the US Army disbanded the 2nd Cavalry, as it fell apart when the War began in 1860).[2] The loss of federal troops led Gov. Hardin R. Runnels in 1858 to re-establish disbanded battalions of Texas Rangers. Thus, on January 27, 1858, Gov. Runnels appointed John Salmon "Rip" Ford, a veteran Ranger of the Mexican-American War and frontier Indian fighter, as captain and commander of the Ranger, Militia and Allied Indian Forces, and ordered him to carry the battle to the Comanches in the heart of the Comancheria.

Ford, whose habit of signing the casualty reports with the initials "RIP" for "Rest In Peace,” was known as a ferocious and no-nonsense Indian fighter. Commonly missing from the history books was his proclivity for ordering the wholesale slaughter of any Indian, man or woman, he could find.[1] Gov. Runnels issued very explicit orders to Ford: "I impress upon you the necessity of action and energy. Follow any trail and all trails of hostile or suspected hostile Indians you may discover and if possible, overtake and chastise them if unfriendly.[3]" Ford then raised a force of approximately 100 Texas Rangers and State Militia. Realizing that even with repeating rifles, buffalo guns and Colt revolvers, he needed additional men, he set out to recruit ones he did not have to pay, as he did his Rangers and Militia.

Recruiting Indian allies

Among the traditional enemies of the Comanche were the Tonkawa Indians, then living on a reservation on the Brazos River, in Texas. The books that immortalize and praise the Tonkawa as friends and allies of the settlers generally downplay the fact the Tonkawa were cannibals, who the Comanche and virtually every other Indian tribe despised and loathed.[4] Ford, however, had no reservations about using cannibals to help him, as long as they were eating Comanches, not Rangers.[3]

On March 19, 1858, Ford went to the Brazos Reservation, near what today is the city of Fort Worth, Texas, to recruit the Tonkawa to join him. An Indian Agent, Capt. L.S. Ross, father of future Governor of Texas Lawrence Sullivan Ross, called Chief Placido of the Tonkawa to a war council where Ross stirred Placido's anger against their mutual enemy. He succeeded in recruiting 120 or so Native Americans in this campaign, 111 of whom were Tonkawa under Chief Placido, hailed as the “faithful and implicitly trusted friend of the whites”, the others being Anadarko and Shawnee, . They joined with approximately an equal number of Texas Rangers to move against the Comanches. Ford's orders from Runnels were to follow any and all trails of hostile and suspected hostile Indians, inflict the most severe punishment (kill them and their families, destroy their homes and food supplies)[1] and allow no interference from “any source”. ("Any source" meant the United States, whose Army and Indian Agents might try to enforce federal treaties and federal law against trespassing on the Indian territories in Oklahoma).[1]

Expedition

Advancing from Texas to Oklahoma

Scouts were sent to locate Comanche camps north of the Red River in the Comancheria. In April 1858 Ford established Camp Runnels near what used to be the town of Belknap. Ford and Placido were determined to follow the Comanche and Kiowa up to their strongholds amid the hills of the Canadian River and into the Witchita Mountains, and if possible kill their warriors, decimate their food supply, strike at their homes and families and generally destroy their ability to make war.[3]

Once he had advanced far into the Texas Comancheria, Ford intended to go further, law or not. On April 15 his Rangers and the Indians from the Brazos Indian Reservation crossed the Red River and advanced into the portion of the Comancheria in the Indian Territories in Oklahoma. Ford knew full well he was violating federal laws and numerous treaties by moving into the Indian Territories, but stated later that his job was to “find and fight Indians, not to learn geography.”[1]

Battle at Little Robe Creek

- Main article Battle of Little Robe Creek.

At dawn on May 12, 1858, Ford attacked a small Comanche village in the Canadian River Valley, flanked by the Antelope Hills. Later that day they attacked a second, which provided much stiffer resistance until its chief, Iron Jacket, was killed. His son, Peta Nocona, arrived with reinforcements, which led to a third distinct clash between the Texas forces and the Comanche. At day's end the Rangers and their allies retreated back to Texas; the Comanches, though in retreat, were gathering reinforcements as more of their tribe arrived, together with Kiowa and Kiowa Apache allies. Having suffered only four Ranger casualties, plus over a dozen Tonkawas, the force killed a reported 76 Comanche and took 16 prisoners and 300 horses. It had burned Iron Jacket's village and the original small village which they had attacked. There is limited mention in history, and none in Ford's official reports on the battle, that the Tonkawa ate their dead Comanche rivals on the night of May 12, 1858, in what is referred to as a "dreadful feast."[3]

Aftermath

Ford returned to Texas and requested that the Governor immediately empower him to raise additional levies of Rangers and return north at once to continue the campaign in the heart of the Comancheria. However, Runnels had exhausted the entire budget for defense for the year, and disbanded the Rangers.

Although Ford was unable to continue this campaign, it changed the face of Indian fighting on the plains and marked the beginning of the end for the Comanche and Kiowa.[1] Only the Civil War delayed the inevitable.[1] For the first time Texan or American forces had penetrated to the heart of the Comancheria, attacked Comanche villages with impunity and successfully made it home. The U.S. Army would adopt many of Ford’s tactics--including his attacking women and children as well as warriors, and destroying their food supply, the buffalo,[1] in their campaigns against the plains tribes after the Civil War.[3]

External links

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fehrenbach, T.R. “Comanches, The Destruction of a People

- 1 2 Wallace, Ernest, and E. Adamson Hoebel. The Comanches: Lords of the Southern Plains. University of Oklahoma Press. 1952.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Richardson, Rupert N. The Comanche Barrier to South Plains Settlement: A Century and a Half of Savage Resistance to the Advancing White Frontier Arthur H. Clarke Co. 1933.

- ↑

- Exley, Jo Ella Powell, “Frontier Blood: The Saga of the Parker Family'',

- Fehrenbach, Theodore Reed The Comanches: The Destruction of a People. New York: Knopf, 1974, ISBN 0-394-48856-3. Later (2003) republished under the title The Comanches: The History of a People

- Foster, Morris. Being Comanche.

- Frazier, Ian. Great Plains. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1989.

- Lodge, Sally. Native American People: The Comanche. Vero Beach, Florida 32964: Rourke Publications, Inc., 1992.

- Lund, Bill. Native Peoples: The Comanche Indians. Mankato, Minnesota: Bridgestone Books, 1997.

- Mooney, Martin. The Junior Library of American Indians: The Comanche Indians. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1993.

- Native Americans: Comanche (August 13, 2005).

- Richardson, Rupert N. The Comanche Barrier to South Plains Settlement: A Century and a Half of Savage Resistance to the Advancing White Frontier. Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1933.

- Rollings, Willard. Indians of North America: The Comanche. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1989.

- Secoy, Frank. Changing Military Patterns on the Great Plains. Monograph of the American Ethnological Society, No. 21. Locust Valley, NY: J. J. Augustin, 1953.

- Streissguth, Thomas. Indigenous Peoples of North America: The Comanche. San Diego: Lucent Books Incorpoqration, 2000.

- "The Texas Comanches" on Texas Indians (August 14, 2005).

- Wallace, Ernest, and E. Adamson Hoebel. The Comanches: Lords of the Southern Plains. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1952.