Louisiana Purchase

| Louisiana Purchase Vente de la Louisiane | |||||

| expansion of United States | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | July 4, 1803 | |||

| • | Disestablished | October 1, 1804 | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

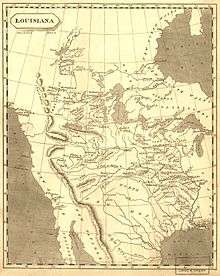

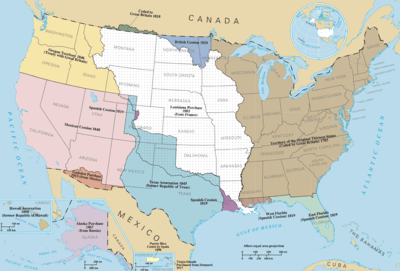

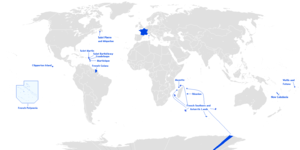

The Louisiana Purchase (French: Vente de la Louisiane "Sale of Louisiana") was the acquisition of the Louisiana territory (828,000 square miles) by the United States from France in 1803. The U.S. paid fifty million francs ($11,250,000 USD) and a cancellation of debts worth eighteen million francs ($3,750,000 USD) for a total of sixty-eight million francs ($15,000,000 USD, or around a quarter of a billion in 2016 dollars). The Louisiana territory included land from fifteen present U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. The territory contained land that forms Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska; the portion of Minnesota west of the Mississippi River; a large portion of North Dakota; a large portion of South Dakota; the northeastern section of New Mexico; the northern portion of Texas; the area of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado east of the Continental Divide; Louisiana west of the Mississippi River (plus New Orleans); and small portions of land within the present Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Its population was around 60,000 inhabitants, of whom half were African slaves.[1]

The Kingdom of France controlled the Louisiana territory from 1699 until it was ceded to Spain in 1762. Napoleon in 1800, hoping to re-establish an empire in North America, regained ownership of Louisiana. However, France's failure to put down the revolt in Saint-Domingue, coupled with the prospect of renewed warfare with the United Kingdom, prompted Napoleon to sell Louisiana to the United States. The Americans originally sought to purchase only the port city of New Orleans and its adjacent coastal lands, but quickly accepted the bargain. The Louisiana Purchase occurred during the term of the third President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. Before the purchase was finalized, the decision faced Federalist Party opposition; they argued that it was unconstitutional to acquire any territory. Jefferson agreed that the U.S. Constitution did not contain explicit provisions for acquiring territory, but he asserted that his constitutional power to negotiate treaties was sufficient.

Background

Throughout the second half of the 18th century, Louisiana was a pawn on the chessboard of European politics.[2] It was controlled by the French, who had a few small settlements along the Mississippi and other main rivers. Following French defeat in the Seven Years' War, Spain gained control of the territory west of the Mississippi. The United States controlled the area east of the Mississippi and north of New Orleans. The main issue for the Americans was free transit of the Mississippi to the sea. As the lands were being gradually settled by a few American migrants, many Americans, including Jefferson, assumed that the territory would be acquired "piece by piece." The risk of another power taking it from a weakened Spain made a "profound reconsideration" of this policy necessary.[2] New Orleans was already important for shipping agricultural goods to and from the areas of the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains. Pinckney's Treaty, signed with Spain on October 27, 1795, gave American merchants "right of deposit" in New Orleans, granting them use of the port to store goods for export. Americans used this right to transport products such as flour, tobacco, pork, bacon, lard, feathers, cider, butter, and cheese. The treaty also recognized American rights to navigate the entire Mississippi, which had become vital to the growing trade of the western territories.[3]

In 1798 Spain revoked this treaty, prohibiting American use of New Orleans, and greatly upsetting the Americans. In 1801, Spanish Governor Don Juan Manuel de Salcedo took over from the Marquess of Casa Calvo, and restored the U.S. right to deposit goods. Napoleon Bonaparte had gained Louisiana for French ownership from Spain in 1800 under the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso, but the treaty was kept secret.

Louisiana remained nominally under Spanish control, until a transfer of power to France on November 30, 1803, just three weeks before the formal cession to the United States on December 20, 1803. Another ceremony was held in St. Louis a few months later, in part because during winter conditions the news of the New Orleans formalities did not reach Upper Louisiana. The March 9–10, 1804, event is remembered as Three Flags Day.

James Monroe and Robert R. Livingston had traveled to Paris to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans in January 1803. Their instructions were to negotiate or purchase control of New Orleans and its environs; they did not anticipate the much larger acquisition which would follow.

The Louisiana Purchase was by far the largest territorial gain in U.S. history. Stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, the purchase doubled the size of the United States. Before 1803, Louisiana had been under Spanish control for forty years. Although Spain aided the rebels in the American Revolutionary War, the Spanish didn't want the Americans to settle in their territory.

Although the purchase was thought of by some as unjust and unconstitutional, Jefferson determined that his constitutional power to negotiate treaties allowed the purchase of what became fifteen states. In hindsight, the Louisiana Purchase could be considered one of his greatest contributions to the United States.[4] On April 18, 1802, Jefferson penned a letter to United States Ambassador to France Robert Livingston. It was an intentional exhortation to make this supposedly mild diplomat strongly warn the French of their perilous course. The letter began:

The cession of Louisiana and the Floridas by Spain to France works most sorely on the U.S. On this subject the Secretary of State has written to you fully. Yet I cannot forbear recurring to it personally, so deep is the impression it makes in my mind. It completely reverses all the political relations of the U.S. and will form a new epoch in our political course. Of all nations of any consideration France is the one which hitherto has offered the fewest points on which we could have any conflict of right, and the most points of a communion of interests. From these causes we have ever looked to her as our natural friend, as one with which we never could have an occasion of difference. Her growth therefore we viewed as our own, her misfortunes ours. There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market, and from its fertility it will ere long yield more than half of our whole produce and contain more than half our inhabitants. France placing herself in that door assumes to us the attitude of defiance. Spain might have retained it quietly for years. Her pacific dispositions, her feeble state, would induce her to increase our facilities there, so that her possession of the place would be hardly felt by us, and it would not perhaps be very long before some circumstance might arise which might make the cession of it to us the price of something of more worth to her. Not so can it ever be in the hands of France. The impetuosity of her temper, the energy and restlessness of her character, placed in a point of eternal friction with us...

Jefferson's letter went on with the same heat to a much quoted passage about "the day that France takes possession of New Orleans." Not only did he say that day would be a low point in France's history, for it would seal America's marriage with the British fleet and nation, but he added, astonishingly, that it would start a massive shipbuilding program.[5]

Negotiation

While the transfer of the territory by Spain back to France in 1800 went largely unnoticed, fear of an eventual French invasion spread nationwide when, in 1801, Napoleon sent a military force to secure New Orleans. Southerners feared that Napoleon would free all the slaves in Louisiana, which could trigger slave uprisings elsewhere.[6] Though Jefferson urged moderation, Federalists sought to use this against Jefferson and called for hostilities against France. Undercutting them, Jefferson took up the banner and threatened an alliance with Britain, although relations were uneasy in that direction.[6] In 1801 Jefferson supported France in its plan to take back Saint-Domingue, (present-day Haiti) then under control of Toussaint Louverture after a slave rebellion.

Jefferson sent Livingston to Paris in 1801 after discovering the transfer of Louisiana from Spain to France under the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. Livingston was authorized to purchase New Orleans.

In January 1802, France sent General Leclerc to Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) to re-establish slavery, which had been abolished in law and in the constitution of the French Republic of 1795—both in France and its colonies—to reduce the rights of free people of color and take back control of the island from Toussaint Louverture, who had maintained St. Domingue as French against invasion by the Spanish and British empires. Before the Revolution, France had derived enormous wealth from St. Domingue at the cost of the lives and freedom of the slaves. Napoleon wanted its revenues and productivity for France restored. Alarmed over the French actions and its intention to re-establish an empire in North America, Jefferson declared neutrality in relation to the Caribbean, refusing credit and other assistance to the French, but allowing war contraband to get through to the rebels to prevent France from regaining a foothold.[7]

In November 1803, France withdrew its 7,000 surviving troops from Saint-Domingue (more than two-thirds of its troops died there) and gave up its ambitions in the Western Hemisphere.[8] In 1804 Haiti declared its independence; but, fearing a slave revolt at home, Jefferson and Congress refused to recognize the new republic, the second in the Western Hemisphere, and imposed a trade embargo against it. This, together with later claims by France to reconquer Haiti, encouraged by Britain, made it more difficult for Haiti to recover after ten years of wars.[9]

In 1803, Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours, a French nobleman, began to help negotiate with France at the request of Jefferson. Du Pont was living in the United States at the time and had close ties to Jefferson as well as the prominent politicians in France. He engaged in back-channel diplomacy with Napoleon on Jefferson's behalf during a visit to France and originated the idea of the much larger Louisiana Purchase as a way to defuse potential conflict between the United States and Napoleon over North America.[10]

Jefferson disliked the idea of purchasing Louisiana from France, as that could imply that France had a right to be in Louisiana. Jefferson had concerns that a U.S. President did not have the constitutional authority to make such a deal. He also thought that to do so would erode states' rights by increasing federal executive power. On the other hand, he was aware of the potential threat that France could be in that region and was prepared to go to war to prevent a strong French presence there.

Throughout this time, Jefferson had up-to-date intelligence on Napoleon's military activities and intentions in North America. Part of his evolving strategy involved giving du Pont some information that was withheld from Livingston. He also gave intentionally conflicting instructions to the two. Desperate to avoid possible war with France, Jefferson sent James Monroe to Paris in 1803 to negotiate a settlement, with instructions to go to London to negotiate an alliance if the talks in Paris failed. Spain procrastinated until late 1802 in executing the treaty to transfer Louisiana to France, which allowed American hostility to build. Also, Spain's refusal to cede Florida to France meant that Louisiana would be indefensible. Monroe had been formally expelled from France on his last diplomatic mission, and the choice to send him again conveyed a sense of seriousness.

Napoleon needed peace with Great Britain to implement the Treaty of San Ildefonso and take possession of Louisiana. Otherwise, Louisiana would be an easy prey for Britain or even for the United States. But in early 1803, continuing war between France and Britain seemed unavoidable. On March 11, 1803, Napoleon began preparing to invade Britain.

A slave revolt in Saint-Domingue (present-day Republic of Haiti) had been followed by the first French general emancipation of slaves in 1793–94. This led to years of war against the Spanish and British empires, which sought to conquer St. Domingue and re-enslave the emancipated population. An expeditionary force under Napoleon's brother-in-law Charles Leclerc in January 1802, supplemented by 20,000 troops over the next 21 months, had tried to reconquer the territory and re-establish slavery. But yellow fever and the fierce resistance of black, mulatto, and white revolutionaries destroyed the French army. This was the culmination of the only successful slave revolt in history, and Napoleon withdrew the surviving French troops in November 1803. In 1804 Haiti became the first independent black-majority state in the New World.[11]

As Napoleon had failed to re-enslave the emancipated population of Haiti, he abandoned his plans to rebuild France's New World empire. Without sufficient revenues from sugar colonies in the Caribbean, Louisiana had little value to him. Spain had not yet completed the transfer of Louisiana to France, and war between France and Britain was imminent. Out of anger against Spain and the unique opportunity to sell something that was useless and not truly his yet, Napoleon decided to sell the entire territory.[12]

Although the foreign minister Talleyrand opposed the plan, on April 10, 1803, Napoleon told the Treasury Minister François de Barbé-Marbois that he was considering selling the entire Louisiana Territory to the United States. On April 11, 1803, just days before Monroe's arrival, Barbé-Marbois offered Livingston all of Louisiana for $15 million, equivalent to about $233 million in 2011 dollars[13] which averages to less than three cents per acre.[14] Adjusting for inflation, the modern financial equivalent spent for the Purchase of the Louisiana territory is approximately $237 million in 2015 U.S. dollars which averages to less than forty-two cents per acre, as of 2010.[15][16]

The American representatives were prepared to pay up to $10 million for New Orleans and its environs, but were dumbfounded when the vastly larger territory was offered for $15 million. Jefferson had authorized Livingston only to purchase New Orleans. However, Livingston was certain that the United States would accept the offer.[17]

The Americans thought that Napoleon might withdraw the offer at any time, preventing the United States from acquiring New Orleans, so they agreed and signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty on April 30, 1803. On July 4, 1803, the treaty reached Washington, D.C.. The Louisiana Territory was vast, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico in the south to Rupert's Land in the north, and from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west. Acquiring the territory would double the size of the United States, at a sum of less than 3 cents per acre.

Domestic opposition and constitutionality

Henry Adams and other historians argue that Jefferson acted hypocritically with the Louisiana Purchase, due to his position as a strict constructionist regarding the Constitution since he stretched the intent of that document to justify his purchase.[18] This argument goes as follows:

The American purchase of the Louisiana territory was not accomplished without domestic opposition. Jefferson's philosophical consistency was in question because of his strict interpretation of the Constitution. Many people believed that he and others, including James Madison, were doing something they surely would have argued against with Alexander Hamilton. The Federalists strongly opposed the purchase, favoring close relations with Britain over closer ties to Napoleon, and were concerned that the United States had paid a large sum of money just to declare war on Spain.

Both Federalists and Jeffersonians were concerned over the purchase's constitutionality. Many members of the House of Representatives opposed the purchase. Majority Leader John Randolph led the opposition. The House called for a vote to deny the request for the purchase, but it failed by two votes, 59–57. The Federalists even tried to prove the land belonged to Spain, not France, but available records proved otherwise.[19]

The Federalists also feared that the power of the Atlantic seaboard states would be threatened by the new citizens in the West, whose political and economic priorities were bound to conflict with those of the merchants and bankers of New England. There was also concern that an increase in the number of slave-holding states created out of the new territory would exacerbate divisions between North and South as well. A group of Northern Federalists led by Senator Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts went so far as to explore the idea of a separate northern confederacy.

Another concern was whether it was proper to grant citizenship to the French, Spanish, and free black people living in New Orleans, as the treaty would dictate. Critics in Congress worried whether these "foreigners", unacquainted with democracy, could or should become citizens.[20]

Spain protested the transfer on two grounds: First, France had previously promised in a note not to alienate Louisiana to a third party and second, France had not fulfilled the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso by having the King of Etruria recognized by all European powers. The French government replied that these objections were baseless since the promise not to alienate Louisiana was not in the treaty of San Ildefonso itself and therefore had no legal force, and the Spanish government had ordered Louisiana to be transferred in October 1802 despite knowing for months that Britain had not recognized the King of Etruria in the Treaty of Amiens.[21]

Henry Adams claimed "The sale of Louisiana to the United States was trebly invalid; if it were French property, Bonaparte could not constitutionally alienate it without the consent of the French Chambers; if it were Spanish property, he could not alienate it at all; if Spain had a right of reclamation, his sale was worthless."[22] The sale of course was not "worthless"—the U.S. actually did take possession. Furthermore, the Spanish prime minister had authorized the U.S. to negotiate with the French government "the acquisition of territories which may suit their interests." Spain turned the territory over to France in a ceremony in New Orleans on November 30, a month before France turned it over to American officials.[23]

Other historians counter the above arguments regarding Jefferson's alleged hypocrisy as follows:

Countries change their borders in two ways: (1) conquest, or (2) an agreement between nations, otherwise known as a treaty. The Louisiana Purchase was the latter, a treaty. The Constitution specifically grants the president the power to negotiate treaties (Art. II, Sec. 2), which is just what Jefferson did.[24]

Jefferson's Secretary of State, James Madison (the "Father of the Constitution"), assured Jefferson that the Louisiana Purchase was well within even the strictest interpretation of the Constitution. Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin added that since the power to negotiate treaties was specifically granted to the president, the only way extending the country's territory by treaty could not be a presidential power would be if it were specifically excluded by the Constitution (which it was not). Jefferson, as a strict constructionist, was right to be concerned about staying within the bounds of the Constitution, but felt the power of these arguments and was willing to "acquiesce with satisfaction" if the Congress approved the treaty.[25]

The Senate quickly ratified the treaty, and the House, with equal alacrity, authorized the required funding, as the Constitution specifies.[26][27]

The opposition of New England Federalists to the Louisiana Purchase was primarily economic self-interest, not any legitimate concern over constitutionality or whether France indeed owned Louisiana or was required to sell it back to Spain should it desire to dispose of the territory. The Northerners were not enthusiastic about Western farmers gaining another outlet for their crops that did not require the use of New England ports. Also, many Federalists were speculators in lands in upstate New York and New England and were hoping to sell these lands to farmers, who might go west instead, if the Louisiana Purchase went through. They also feared that this would lead to Western states being formed, which would likely be Republican, and dilute the political power of New England Federalists.[26][28]

When Spain later objected to the United States purchasing Louisiana from France, Madison responded that America had first approached Spain about purchasing the property, but had been told by Spain itself that America would have to treat with France for the territory.[29]

Treaty signing

The Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed on 30 April by Robert Livingston, James Monroe, and Barbé Marbois in Paris. Jefferson announced the treaty to the American people on July 4. After the signing of the Louisiana Purchase agreement in 1803, Livingston made this famous statement, "We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives...From this day the United States take their place among the powers of the first rank."[30]

The United States Senate ratified the treaty with a vote of twenty-four to seven on October 20. The Senators who voted against the treaty were: Simeon Olcott and William Plumer of New Hampshire, William Wells and Samuel White of Delaware, James Hillhouse and Uriah Tracy of Connecticut, and Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts.

On the following day, October 21, 1803, the Senate authorized Jefferson to take possession of the territory and establish a temporary military government. In legislation enacted on October 31, Congress made temporary provisions for local civil government to continue as it had under French and Spanish rule and authorized the President to use military forces to maintain order. Plans were also set forth for several missions to explore and chart the territory, the most famous being the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Formal transfers and initial organization

France turned over New Orleans, the historic colonial capital, on December 20, 1803, at the Cabildo, with a flag-raising ceremony in the Plaza de Armas, now Jackson Square. Just three weeks earlier, on November 30, 1803, Spanish officials had formally conveyed the colonial lands and their administration to France.

On March 9 and 10, 1804, another ceremony, commemorated as Three Flags Day, was conducted in St. Louis to transfer ownership of Upper Louisiana from Spain to the French First Republic, and then from France to the United States. From March 10 to September 30, 1804, Upper Louisiana was supervised as a military district, under Commandant Amos Stoddard.

Effective October 1, 1804, the purchased territory was organized into the Territory of Orleans (most of which would become the state of Louisiana) and the District of Louisiana, which was temporarily under control of the governor and judicial system of the Indiana Territory. The following year, the District of Louisiana was renamed the Territory of Louisiana, aka Louisiana Territory (1805–1812).

New Orleans was the administrative capital of the Orleans Territory, and St. Louis was the capital of the Louisiana Territory.

Boundaries

A dispute soon arose between Spain and the United States regarding the extent of Louisiana. The territory's boundaries had not been defined in the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau that ceded it from France to Spain, nor in the 1801 Third Treaty of San Ildefonso ceding it back to France, nor the 1803 Louisiana Purchase agreement ceding it to the United States.[31]

The United States claimed Louisiana included the entire western portion of the Mississippi River drainage basin to the crest of the Rocky Mountains and land extending southeast to the Rio Grande and West Florida.[32] Spain insisted that Louisiana comprised no more than the western bank of the Mississippi River and the cities of New Orleans and St. Louis.[33] The dispute was ultimately resolved by the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, with the United States gaining most of what it had claimed in the west.

The relatively narrow Louisiana of New Spain had been a special province under the jurisdiction of the Captaincy General of Cuba while the vast region to the west was in 1803 still considered part of the Commandancy General of the Provincias Internas. Louisiana had never been considered one of New Spain's internal provinces.[34]

If the territory included all the tributaries of the Mississippi on its western bank, the northern reaches of the Purchase extended into the equally ill-defined British possession—Rupert's Land of British North America, now part of Canada. The Purchase originally extended just beyond the 50th parallel. However, the territory north of the 49th parallel (including the Milk River and Poplar River watersheds) was ceded to the UK in exchange for parts of the Red River Basin south of 49th parallel in the Anglo-American Convention of 1818.

The eastern boundary of the Louisiana purchase was the Mississippi River, from its source to the 31st parallel, though the source of the Mississippi was, at the time, unknown. The eastern boundary below the 31st parallel was unclear. The U.S. claimed the land as far as the Perdido River, and Spain claimed that the border of its Florida Colony remained the Mississippi River. In early 1804, Congress passed the Mobile Act, which recognized West Florida as part of the United States. The Adams–Onís Treaty with Spain (1819) resolved the issue upon ratification in 1821. Today, the 31st parallel is the northern boundary of the western half of the Florida Panhandle, and the Perdido is the western boundary of Florida.

Because the western boundary was contested at the time of the Purchase, President Jefferson immediately began to organize three missions to explore and map the new territory. All three started from the Mississippi River. The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804) traveled up the Missouri River; the Red River Expedition (1806) explored the Red River basin; the Pike Expedition (1806) also started up the Missouri, but turned south to explore the Arkansas River watershed. The maps and journals of the explorers helped to define the boundaries during the negotiations leading to the Adams–Onís Treaty, which set the western boundary as follows: north up the Sabine River from the Gulf of Mexico to its intersection with the 32nd parallel, due north to the Red River, up the Red River to the 100th meridian, north to the Arkansas River, up the Arkansas River to its headwaters, due north to the 42nd parallel and due west to its previous boundary.

Slavery

Governing the Louisiana Territory was more difficult than acquiring it. Its European peoples, of ethnic French, Spanish and Mexican descent, were largely Catholic; in addition, there was a large population of enslaved Africans made up of a high proportion of recent arrivals, as Spain had continued the international slave trade. This was particularly true in the area of the present-day state of Louisiana, which also contained a large number of free people of color. Both present-day Arkansas and Missouri already had some slaveholders in the early 19th century.

During this period, south Louisiana received an influx of Francophone refugee planters, who were permitted to bring their slaves with them, and other refugees fleeing the large slave revolt in Saint-Domingue, today's Haiti. Many Southern slaveholders feared that acquisition of the new territory might inspire American-held slaves to follow the example of those in Saint-Domingue and revolt. They wanted the US government to establish laws allowing slavery in the newly acquired territory so they could be supported in taking their slaves there to undertake new agricultural enterprises, as well as to reduce the threat of future slave rebellions.[35]

The Louisiana Territory was broken into smaller portions for administration, and the territories passed slavery laws similar to those in the southern states but incorporating provisions from the preceding French and Spanish rule (for instance, Spain had prohibited slavery of Native Americans in 1769, but some slaves of mixed African-Native American descent were still being held in St. Louis in Upper Louisiana when the U.S. took over).[36] In a freedom suit that went from Missouri to the US Supreme Court, slavery of Native Americans was finally ended in 1836.[36] The institutionalization of slavery under U.S. law in the Louisiana Territory contributed to the American Civil War a half century later.[35] As states organized within the territory, the status of slavery in each state became a matter of contention in Congress, as southern states wanted slavery extended to the west, and northern states just as strongly opposed new states being admitted as "slave states."

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was a temporary solution.

Asserting U.S. possession

After the early explorations, the U.S. government sought to establish control of the region, since trade along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers was still dominated by British and French traders from Canada and allied Indians, especially the Sauk and Fox. The U.S. adapted the former Spanish facility at Fort Bellefontaine as a fur trading post near St. Louis in 1804 for business with the Sauk and Fox.[37] In 1808 two military forts with trading factories were built, Fort Osage along the Missouri River in western present-day Missouri and Fort Madison along the Upper Mississippi River in eastern present-day Iowa.[38] With tensions increasing with Great Britain, in 1809 Fort Bellefontaine was converted to a U.S. military fort, and was used for that purpose until 1826.

During the War of 1812, Great Britain and allied Indians defeated U.S. forces in the Upper Mississippi; the U.S. abandoned Forts Osage and Madison, as well as several other U.S. forts built during the war, including Fort Johnson and Fort Shelby. After U.S. ownership of the region was confirmed in the Treaty of Ghent (1814), the U.S. built or expanded forts along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, including adding to Fort Bellefontaine, and constructing Fort Armstrong (1816) and Fort Edwards (1816) in Illinois, Fort Crawford (1816) in Prairie du Chien Wisconsin, Fort Snelling (1819) in Minnesota, and Fort Atkinson (1819) in Nebraska.[38]

Financing

The American government used $3 million in gold as a down payment, and issued bonds for the balance to pay France for the purchase. Earlier that year, Francis Baring and Company of London had become the U.S. government's official banking agent in London. Because of this favored position, the U.S. asked the Baring firm to handle the transaction. Francis Baring's son Alexander was in Paris at the time and helped in the negotiations.[39] Another Baring advantage was a close relationship with Hope and Company of Amsterdam. The two banking houses worked together to facilitate and underwrite the Purchase.

Because Napoleon wanted to receive his money as quickly as possible, the two firms received the American bonds and shipped the gold to France.[39] Napoleon used the money to finance his planned invasion of England, which never took place.[40]

See also

- Alaska Purchase

- Florida Purchase

- Corps of Discovery

- Franco-American alliance

- List of French possessions and colonies

- Historic regions of the United States

- Louisiana Purchase Historic State Park

- Territorial evolution of the United States

- Territories of the United States on stamps

References

Footnotes

- ↑ https://books.google.ca/books?id=PHhHAQAAIAAJ&pg=RA5-PA56&lpg=RA5-PA56&dq=Population+of+Louisiana+in+1803&source=bl&ots=prZATylP7n&sig=eGgBIe_oWJHNU_K9ASi1CF9EGjY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CFIQ6AEwCGoVChMIp9bcyfDPxwIVglg-Ch0i1wWJ#v=onepage&q=Population%20of%20Louisiana%20in%201803&f=false

- 1 2 Herring (2008), p. 99

- ↑ Meinig (2003)

- ↑ Thompson (2006), pp. 4–48

- ↑ Cerami (2003), pp. 57-58

- 1 2 Herring (2008), p. 100

- ↑ Matthewson (1995), p. 221

- ↑ Matthewson (1995), p. 209

- ↑ Matthewson (1996), pp. 22–23

- ↑ Duke (1977), pp. 77–83

- ↑ "A Revolution in Haiti". University of Miami Libraries. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ↑ Herring (2008), p. 101

- ↑ http://www.investopedia.com/financial-edge/1012/3-of-the-most-lucrative-land-deals-in-history.aspx

- ↑ "Primary Documents of American History: Louisiana Purchase". Web Guides. Library of Congress. March 29, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Kennedy, Cohen & Bailey (2008).

- ↑ Burgan (2002), p. 36.

- ↑ Malone, Roeder & Lang (1991), p. 30

- ↑ Rodriguez (2002), pp. 139–40

- ↑ Fleming (2003), pp. 149ff

- ↑ Nugent (2009), pp. 65–68.

- ↑ Gayarre (1867), p. 544.

- ↑ Adams (2011), pp. 56–57

- ↑ Nugent (2009), pp. 66–67

- ↑ Lawson & Seidman (2008), pp. 20–22

- ↑ Banning (1995), pp. 7–9, 178, 326–7, 330–3, 345–6, 360–1, 371, 384.

- 1 2 Ketcham (2003), pp. 420–2.

- ↑ The fledgling United States did not have $15 million in its treasury; it borrowed the sum from Great Britain, at an annual interest rate of six percent.

- ↑ Lewis (2003), p. 79

- ↑ Peterson, Merrill D. (1974). "James Madison: A Biography in his Own Words". Newsweek. pp. 237–46.

- ↑ "America's Louisiana Purchase: Noble Bargain, Difficult Journey". Lpb.org. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ↑ Schoultz (1998), pp. 15–16

- ↑ Haynes (2010), pp. 115–16

- ↑ Hämäläinen (2008), p. 183

- ↑ Weber (1994), pp. 223, 293

- 1 2 Herring (2008), p. 104

- 1 2 Foley, William E. (October 1984). "Slave Freedom Suits before Dred Scott: The Case of Marie Jean Scypion's Descendants". Missouri Historical Review. 79 (1): 1. Retrieved February 18, 2011 – via The State Historical Society of Missouri.

- ↑ Luttig (1920).

- 1 2 Prucha (1969).

- 1 2 Ziegler (1988).

- ↑ Fleming (2003), pp. 129ff.

Works cited

- Adams, Henry (2011) [1889]. History of the United States of America (1801–1817). vol.2: During the First Administration of Thomas Jefferson. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108033039.

- Banning, Lance (1995). The Sacred Fire of Liberty: James Madison and the Founding of the Federal Republic. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Burgan, Michael (2002). The Louisiana Purchase. Capstone. ISBN 9780756502102.

- Cerami, Charles A. (2003). Jefferson's Great Gamble. Sourcebooks. ISBN 9781402234354.

- Duke, Marc (1977). The du Ponts: Portrait of a Dynasty. Saturday Review Press. ISBN 0-8415-0429-6.

- Fleming, Thomas J. (2003). The Louisiana Purchase. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-26738-6.

- Gayarre, Charles (1867). History of Louisiana.

- Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- Haynes, Robert V. (2010). The Mississippi Territory and the Southwest Frontier, 1795–1817. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2577-0.

- Herring, George (2008). From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-976553-7.

- Ketcham, Ralph (2003). James Madison: A Biography. Newtown CT: American Political Biography Press. ISBN 9780813912653.

- Kennedy, David M.; Cohen, Lizabeth & Bailey, Thomas Andrew (2008). The American Pageant: A History of the American People. Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-547-16654-4.

- Lawson, Gary & Seidman, Guy (2008). The Constitution of Empire: Territorial Expansion and American Legal History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300128967.

- Lewis, James E., Jr. (2003). The Louisiana Purchase: Jefferson's Noble Bargain?. UNC Press Books.

- Luttig, John C. (1920). Journal of a Fur-trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri: 1812–1813. Kansas City MO: The Missouri Historical Society.

- Malone, Michael P.; Roeder, Richard B. & Lang, William L. (1991). Montana: A History of Two Centuries. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97129-0.

- Meinig, D.W. (1993). The Shaping of America: Volume 2. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300062908.

- Matthewson, Tim (May 1995). "Jefferson and Haiti". The Journal of Southern History. 61 (2): 209–48. JSTOR 2211576.

- Matthewson, Tim (March 1996). "Jefferson and the Non-Recognition of Haiti". American Philosophical Society. 140 (1): 22–48. JSTOR 987274.

- Nugent, Walter (2009). Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansionism. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-7818-9.

- Prucha, Francis P. (1969). The Sword of the Republic: The United States Army on the Frontier 1783–1846. New York: Macmillan.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576071885.

- Schoultz, Lars (1998). Beneath the United States. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-92276-1.

- Thompson, Linda (2006). The Louisiana Purchase. Rourke Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59515-513-9.

- Weber, David J. (1994). The Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05917-5.

- Ziegler, Philip (1988). The Sixth Great Power: Barings 1762–1929. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-217508-8.

Further reading

- Hermann (1900). The Louisiana Purchase and our title west of the Rocky Mountains: with a review of annexation by the United States.

- Hosmer, James Kendall (1902). Louisiana Purchase. New York: D. Appleton & Co.

- Marshall (1914). A History of the Western Boundary of the Louisiana Purchase, 1819-1841.

- U.S. Dept. of State (1903). State papers and correspondence bearing upon the purchase of the territory of Louisiana.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louisiana Purchase. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Text of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty

- Library of Congress: Louisiana Purchase Treaty

- Teaching about the Louisiana Purchase

- Louisiana Purchase Bicentennial 1803–2003*Lewis and Clark Trail

- Louisiana Purchase and Lewis & Clark student and teacher guide: dates, people, analysis, multimedia

- New Orleans/Louisiana Purchase 1803

- The Haitian Revolution and the Louisiana Purchase

- Case and Controversies in U.S. History, Page 42 Senator Pickering explains his opposition to the Louisiana Purchase, 1803.

- Booknotes interview with Jon Kukla on A Wilderness So Immense: The Louisiana Purchase and the Destiny of America, July 6, 2003.

.svg.png)