Anthony Kohlmann

Anthony Kohlmann, S.J. (13 July 1771 – 11 April 1836), was an Alsatian Jesuit priest. He is known for his part in the establishment of confessional privilege in United States law. He spent nearly a quarter of a century in that nation as an educator.

Life

Early life

Kohlmann was born at Kaysersberg, then in the ancient province of Alsace, in the Kingdom of France. He had joined the Capuchins but was compelled by the troubles of the French Revolution to go to Switzerland, where at the seminary of Fribourg he completed his theological studies and was ordained a priest in 1796.[1] Soon after he joined the Congregation of the Fathers of the Sacred Heart, founded by Tourneley and de Broglia in Vienna. With them he spent some time in Austria, where he distinguished himself by his tireless efforts during a plague at Hagenbrunn. He then served as a military chaplain at a hospital in Pavia. In 1801 he was sent from Italy to Dillingen in Bavaria, as director of a seminary, then to Berlin, and next to Amsterdam, to direct a college established by the Fathers of the Faith of Jesus, with whom the Congregation of the Sacred Heart had united (11 April 1799).

Jesuit

The Jesuits in Russia, still functioned as a religious community after the suppression of the Society of Jesus in Catholic Europe, and were recognized in 1801 by Pope Pius VII. Kohlmann applied for admission to the Society, and while waiting for a response spent time at Kensington College in London. He went to Russia and entered the Jesuit novitiate on 21 June 1803. In response to a call for additional workers in the United States, he was sent to Georgetown, D.C., arriving in Baltimore on November 4, 1806. Here he was made assistant to the Master of novices,[1] and would undertake preaching tours to German-speaking congregations in Pennsylvania and Maryland. His missionary travels to the largely German Catholic community took him to Alexandria, Philadelphia, Lancaster, Colman's Furnace, and Baltimore.

United States

New York

In March 1808, German Catholics in New York had written Bishop John Carroll, then the leader of the Catholic Church for the entire nation, requesting that he send them a German-speaking priest, so that they could be ministered to in their own language. Prior to that they were able to have services at St. Peter's when a missionary from Pennsylvania would occasionally visit. Bishop Carroll appointed Father Anthony S.J., who arrived later that year with his fellow Jesuits, Benedict Fenwick and four scholastics (seminarians), James Wallace, Michael White, James Redmond and Adam Marshall, he took charge there in October 1808, apostolic administrator.[1] Father Kohlmann succeeded Matthew Byrne as rector of St. Peter's. (Father Byrne wished to resign as pastor of St. Peter's parish in order to enter the Society of Jesus.)

It was a time of great commercial depression in the city owing to the results of the Embargo Act of 22 December 1807. The Catholic population, he states in a letter written on 8 November 1808, consisted "of Irish, some hundreds of French and as many Germans; in all according to the common estimation of 14,000 souls".[2]In 1808 Kohlmann was named Vicar General for Bishop Luke Concanen, the newly appointed bishop of New York, whose departure from Rome was delayed by Napoleon's control of Italian ports.

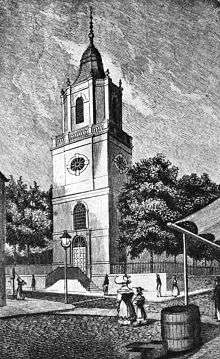

Such progress was made under his direction that the cornerstone of a new church, the original St. Patrick's Cathedral, the second church erected in New York, was laid on 8 June 1809. He selected a site, at that time, outside the city, surrounded by country homes of the wealthy and scattered farms. Sermons were preached on Sundays in English, French and German.

Kohlmann started a classical school called the New York Literary Institution, which he carried on successfully for several years in what was then a suburban village but is now the site of St. Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. In April 1812, he also started a school for girls in the same neighborhood, in the charge of Ursuline nuns who came at his invitation for that purpose from their monastery in County Cork, Ireland.

Seal of the confessional

About this same time Kohlmann became the central figure in a lawsuit that stirred national interest. He had been instrumental in having stolen goods restored to the owner. When the owner then requested that the police drop the case, they insisted that he revealed the identity of the man who had returned the goods, and then that Father Kohlman reveal from whom he had received them. Kohlmann refused to do this, on the ground that his information had been received under the seal of the confessional. The case was taken before the New York Court of Chancery, where Kohlmann's defence lawyer was an Irish Protestant named William Sampson. After a trial, the decision rendered by then Mayor De Witt Clinton, was rendered in the priest's favor.[3]

It is essential to the free exercise of a religion, that its ordinances should be administered – that its ceremonies as well as its essentials should be protected. Secrecy is of the essence of penance. The sinner will not confess, nor will the priest receive his confession, if the veil of secrecy is removed...[3]

This was the first legal affirmation of confessional privilege in American history, and a key moment in Americas tradition of freedom of religion.[3] The principle was later embodied in New York State law passed on 10 December 1828, which enacted that: "No minister of the Gospel or priest of any denomination whatsoever shall be allowed to disclose any confession made to him in his professional character in the course of discipline enjoined by the rules or practices of such denomination." The protection from being forced to testify or provide information to law enforcement agencies became accepted nationwide in the United States.

To a report of the case when published, Kohlmann added an exposition of the teachings of the Church on penance. [4] The book excited a long and vigorous controversy with a number of Protestant ministers, and was followed in 1821 by another learned work, "Unitarianism, Theologically and Philosophically considered", in which Kohlmann replied to the assertions of Jared Sparks and other Unitarian leaders.

Georgetown

New York had no bishop of its own as yet, the first appointed having died in Italy before he reached his see, and Kohlmann governed as its Apostolic Administrator for several years. In 1815, expecting the imminent arrival of the second bishop, John Connolly, he returned to Georgetown, where he served as Master of novices, and in 1817 became superior. He served as the President of Georgetown College from 1817-1820. In 1821 Kohlman founded the Washington Seminary, which later became Gonzaga College High School.[2]

The miracle

Shortly afterwards Kohlmann became interested in the work of the Rev. Prince Alexander von Hohenlohe, a charismatic German priest and nobleman who claimed to be able to effect miracle cures. Hohenlohe was supposed, in particular, to have saved the life of a German princess, Mathilda von Schwarzenburg, when he and a peasant associate prayed over her. The case was much publicized, and, although the Catholic authorities in Europe never endorsed Hohenlohe’s cures, many, including Kohlmann, believed in them.

In 1824 Kohlman learned that a prominent Washington Catholic, Mrs. Ann Mattingly, was suffering from cancer, and decided to contact Hohenlohe in an effort to cure her. He wrote to the princely miracle-worker in Bamberg, Germany, and got him to agree to pray for Mrs. Mattingly at a certain precise time several months later. In Washington he arranged for one of his Jesuit colleagues to say Mass by her bedside at the chosen hour, while he celebrated yet another Mass in the Georgetown University chapel.

These trans-Atlantic negotiations took some time, and meanwhile Mattingly’s condition worsened. Her brother, Thomas Carbery, the Mayor of the District of Columbia, protested to Kohlmann that she would be dead before the prayer session could occur, but the Jesuit told him not to worry, that the splendor of the miracle would be all the greater for occurring at the very last minute. At the appointed time, the three priests said their Masses in their respective locations. Soon afterwards Mattingly arose from her bed, proclaimed herself entirely cured, and went on to live in good health for another 30 years.[2]

The story of her cure attracted great interest in the press. To some Catholics it was proof of the power of prayer and of the superiority of their religion, while to Protestants and “free thinkers”, it smacked of medieval superstition and priestly chicanery. The Catholic hierarchy stood aloof from the conflict, and none of Hohenlohe’s “miracles” was ever endorsed by the Church, and certainly not the cure of Mrs. Mattingly, at which he had not even been present.

Later life

Later that year, when Pope Leo XII restored the Gregorian University to the direction of the Society of Jesus, Kohlmann was summoned to Rome to take the Chair of Theology, which he filled for five years. One of his pupils then was the subsequent Pope Leo XIII; another became later Archbishop of Dublin, and the first Irish cardinal (Paul Cullen). Popes Leo XII and Gregory XVI both held Kohlmann in high esteem, and had him attached as a consultant to the staffs of the College of Cardinals and several of the important Congregations, including that of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, of Bishops and Regulars.[5]

The last part of his life he spent as a confessor in the Church of the Gesù in Rome, where during the Lenten season of 1836 he overtaxed himself and brought on an attack of pneumonia that ended his career.[5]

Legacy

Father Kohlmann's defense of the "seal of the confessional" led to the statutory recognition of the "confessional privilege" in New York State law, later followed by other jurisdictions.

Fordham University's Kohlmann Hall is the residence hall for the Jesuits teaching at Fordham Prep.[6]

Notes

- 1 2 3 "April 10 1836 - Antthony Kohlmann SJ dies, giant of restored society", Jesuit Restoration 1814

- 1 2 3 Parsons S. J., J. Wilfrid. "Rev. Anthony Kohlmann, S. J. (1771-1824)", The Catholic Historical Review, Vol. 4, No. 1, Apr., Catholic University of America Press, 1918

- 1 2 3 "14 June 1813 - Fr Kohlmann aquitted [sic] in landmark trial in US", Jesuit Restoration 1814

- ↑ Sampson, William. "The Catholic Question in America", appendix, New York, 1813

- 1 2 Meehan, Thomas. "Antony Kohlmann." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 6 Oct. 2014

- ↑ "Kohlmann Hall", Fordham University

References

- John Gilmary Shea, The Catholic Church in the U. S. (New York 1856);

- Bayley, A Brief Sketch of the Early History of the Catholic Church in the Island of N. Y. (New York. 1870);

- Joseph Finotti, Bibliog. Cath. Am. (New York, 1872);

- Farley, History of St. Patrick's Cathedral (New York 1908);

- U. S. Cath. Hist. Soc., Hist. Records and Studies, I (New York, 1899), pt. i ;

- The Catholic Family Almanac (New York, 1872).

External links

- Garrity, Jim. "Religious Freedom at Heart of New York Case Two Centuries Ago", Catholic New York, June 27, 2012

"Kohlmann, Anthony". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Kohlmann, Anthony". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "article name needed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "article name needed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

| Educational offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Benedict Joseph Fenwick, S.J. #10 |

President of Georgetown University 1817-1820 #11 |

Succeeded by Enoch Fenwick, S.J. #12 |