Nuclear power in Sweden

Sweden began research into nuclear energy in 1947 with the establishment of the Atomic Energy Company, which originated in the ongoing military research and development at the Defence Institute FOA.[1] In 1954, the country built its first small research heavy water reactor. It was followed by two heavy water reactors: Ågesta, a small heat and power reactor in 1964, and Marviken which was finished but never operated, due to several safety issues.[2] Both were heavy water reactors, motivated by the option to use Swedish uranium without isotope enrichment. The option to use plutonium from power reactors was closed only in 1968 with the signing of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. The switch to light water reactors started a few years earlier with Oskarshamn 1.

Six nuclear reactors began commercial service in the 1970s, another six through 1985, with one unit closed in 1999 and another in 2005. Nine of the reactors were designed by ASEA, three supplied by Westinghouse. Sweden has three operational nuclear power plants, with ten operational nuclear reactors, which produce about 35-40% of the country's electricity.[3] The nation's largest power station, Ringhals Nuclear Power Plant, has four reactors and generates about 15 percent of Sweden's annual electricity consumption.[4] The power plants in Forsmark and Oskarshamn each have three reactors.

Sweden formerly had a nuclear phase-out policy, aiming to end nuclear power generation in Sweden by 2010. On 5 February 2009, the Government of Sweden announced an agreement allowing for the replacement of existing reactors, effectively ending the phase-out policy.[5]

Commercial reactors

| Site | Unit | Reactor type | Net power generation | Constructor | Commission date | Decommission date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barsebäck Nuclear Power Plant | B1 | ABB-II (Boiling water reactor) | 600 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1975 | 1999 |

| B2 | ABB-II (Boiling water reactor) | 600 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1977 | 2005 | |

| Ringhals Nuclear Power Plant | R1 | ABB-I (Boiling water reactor) | 881 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1976 | 2020 |

| R2 | Pressurized water reactor | 807 MW | Westinghouse | 1975 | 2019 | |

| R3 | Pressurized water reactor | 1063 MW | Westinghouse | 1981 | ||

| R4 | Pressurized water reactor | 1115 MW | Westinghouse | 1983 | ||

| Oskarshamn Nuclear Power Plant | O1 | ABB-I (Boiling water reactor) | 473 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1972 | 2019 |

| O2 | ABB-II (Boiling water reactor) | 638 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1975 | 2020 | |

| O3 | ABB-II (Boiling water reactor) | 1400 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1985 | ||

| Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant | F1 | ABB-III (Boiling water reactor) | 984 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1980 | |

| F2 | ABB-III (Boiling water reactor) | 1120 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1981 | ||

| F3 | ABB-III (Boiling water reactor) | 1170 MW | ASEA-Atom | 1985 |

Chronology

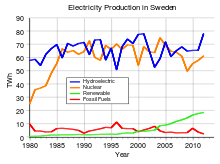

Electricity production in Sweden is dominated by nuclear power and hydroelectricity which currently make about equal contributions to energy production, for which demand has remained fairly constant since 1990.

On 1 May 1969, a prototype nuclear cogeneration plant outside Stockholm, Ågestaverket (R3) suffered an incident in which secondary cooling water flooded through a broken valve and caused a number of electrical problems in the plant, resulting in a 4-day shutdown.[6]

R1, R3, and particularly the never finished R4 project at Marviken were heavy water reactors which could have been used to produce weapons grade plutonium for Swedish nuclear warheads. The Swedish nuclear weapons programme was eventually shut down, however, and Sweden signed the nuclear non-proliferation treaty in 1968.[7]

After the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, there was a national referendum in Sweden about the future of nuclear power there. As a result of this, the Riksdag decided in 1980 that no further nuclear power plants should be built, and that a nuclear power phase-out should be completed by 2010. Some observers have condemned the referendum as flawed because people could only vote "NO to nuclear", although three options were basically a harder or a softer "NO".

After the 1986 Chernobyl accident in Ukraine, the question of security of nuclear energy was again raised. In July 1992 an incident at Barsebäck 2 showed that the five older boiling water reactors had had potentially reduced capacity in their emergency core cooling systems since they started operation. Mineral wool was dislodged and ended up in the suppression pool where it clogged the suction strainers.[8] It was classified as a grade 2 incident in the IAEA INES scale, due to the degradation of defence-in-depth. All five reactors were ordered down by the Nuclear Inspectorate for remedial action where backwash and additional strainers were installed. Most of the reactors were back in operation by next Spring, but Oskarshamn 1 remained down till January 1996 due to other work being carried out.

During the late 1990s a unique capacity tax on nuclear power (effektskatten) was introduced. It was initially set at 5514 SEK per MWth per month, and only applied to nuclear power plants, thus penalising them relative to other energy sources. In January 2006 it was almost doubled (at 10,200 SEK per MWth per month).[9] An agreement struck in June 2016 among other things meant the capacity tax would be phased out by 2019. By then the tax constituted about one third of the cost of operating a nuclear reactor.[10]

In 1997 the Riksdag decided to shut down one of the reactors at Barsebäck by 1 July 1998 and the second before 1 July 2001, although under the condition that their energy production would be compensated. The next conservative government tried to cancel the phase-out, but, after protests, did not cancel it but instead decided to extend the time limit to 2010. At Barsebäck, block 1 was shut down on 30 November 1999 and block 2 on 1 June 2005.

In June 2005, radioactive water was detected leaking from the nuclear waste store in Forsmark, Sweden. The content of radioactive caesium in the water sampled was ten times the normal value. wikinews:Radioactive leakage at Swedish nuclear waste store.

In August 2006 three of Sweden's ten nuclear reactors were shut down due to safety concerns following an incident at Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant, in which two out of four emergency power generators failed causing a power shortage. It was classified as a grade 2 incident in the IAEA INES scale, due to the degradation of defence-in-depth. In 2006 the Centre Party of Sweden, an opposition party that supported the phase-out, announced that it is dropping its opposition to nuclear power, at least for the time being, claiming that it is unrealistic to expect the phase-out in the short term. It said it would now support the stance of the other opposition parties in Alliance for Sweden, which were considerably more pro-nuclear than the then Social Democratic government.[11]

On 17 June 2010, the Riksdag adopted a decision allowing the replacement of the existing reactors with new nuclear reactors, starting from 1 January 2011.[12]

Public opinion

The nuclear energy phase-out is controversial in Sweden. The energy production of the remaining nuclear power plants has been considerably increased in recent years to compensate for the Barsebäck shut-down.

In May 2005, a poll of residents living around Barsebäck found that 94% wanted it to stay. The subsequent leak of radioactive water from the nuclear waste store in Forsmark did not lead to a major change in public opinion.[13] According to a poll of January 2008, 48% of Swedes were in favour of building new nuclear reactors, 39% were opposed and 13% were undecided. However, the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan reversed prior support of nuclear power, with polls showing that 64% of Swedes opposed new reactors while 27% supported them.[14]

Prior public support for nuclear power stood in contrast to the stances of the major political parties in Sweden, the only one of which in favour of building new reactors is the Liberal party.[15]

The advisory referendum on nuclear power (1980)

As a consequence of the debate following the Three Mile Island accident, an advisory referendum was held in Sweden on 23 March 1980. Swedish voters were given three choices:

- The ballot for "Linje 1" read:

- "Nuclear power shall be phased out, while taking consideration of the need for electric power for the maintenance of employment and welfare. In order to, among other things, lessen the dependency on oil, and while waiting for the availability of renewable energy sources, at most 12 of the reactors shall be used, be they existing or under construction. No further expansion is to take place. The order in which the reactors will be taken out of production will be determined by security concerns."

- There was no text on the reverse side of the ballot.

- The front side of the ballot for "Linje 2" had almost identical wording to that of "Linje 1". However, on the reverse side, the following text was added:

- "Energy conservation shall be pursued vigorously and stimulated further. The weakest groups in society shall be protected. Measures shall be taken to control consumption of electricity, e.g. prohibiting direct electric heating in the construction of new permanent housing.

- Research and development of renewable energy sources shall be pursued under the leadership of the community [government].

- Environmental and safety improving measures are to be carried out. A special safety study is to be made at each reactor. To allow insight by the citizens a special security committee with local ties is appointed at each nuclear power plant.

- Production of electricity from oil and coal is to be avoided.

- The community [government] shall have the main responsibility for production and distribution of electric power. Nuclear power plants and other future installations for the production of significant electric power shall be owned by the state and by the municipalities. Excessive profits from hydroelectric power generation are reduced by taxation."

- The last point was controversial and the most important reason why the Moderate Party would not consider supporting "Linje 2".

- The front side of the ballot for "Linje 3" read:

- "NO to continued expansion of nuclear power.

- Phasing out of the currently operating six reactors with at most ten years. A conservation plan for reduced dependency on oil is to be carried through on the basis of:

- continued and intensified energy conservation

- greatly increased development of renewable energy sources.

- Phasing out of the currently operating six reactors with at most ten years. A conservation plan for reduced dependency on oil is to be carried through on the basis of:

- The operating reactors are subjected to heightened safety requirements. Non-fueled reactors will never be put into production.

- Uranium mining is to be prohibited in our country."

- The reverse side of the ballot read:

- "If ongoing or future safety analyses demand it, immediate shutdown is to take place.

- The work against nuclear proliferation and nuclear weapons shall be intensified. No fuel enrichment is permitted and the export of reactors and reactor technology is to cease.

- Employment will increase through alternative energy production, more effective conservation of energy and refinement of raw materials."

The results of the referendum were 18.9% in support of alternative 1, 39.1% for alternative 2, and 38.7% for alternative 3.[16] Following the referendum the Riksdag decided that no further nuclear power plants should be built and that a nuclear power phaseout should be completed by 2010.

Nuclear waste

Sweden has a well-developed nuclear waste management policy. Low-level waste is currently stored at the reactor sites or destroyed at Studsvik. The country has dedicated a ship, M/S Sigyn, to move waste from power plants to repositories. Sweden has also constructed a permanent underground repository, SFR, final repository for short-lived radioactive waste, with a capacity of 63,000 cubic meters for intermediate and low-level waste. A central interim storage facility for spent nuclear fuel, Clab, is located near Oskarshamn. The government has also identified two potential candidates for burial of additional waste (high-level), Oskarshamn and Östhammar.[17]

Anti-nuclear activists

In June 2010, Greenpeace anti-nuclear activists invaded Forsmark nuclear power plant to protest the then-plan to remove the government prohibition on building new nuclear power plants. In October 2012, 20 Greenpeace activists scaled the outer perimeter fence of the Ringhals nuclear plant, and there was also an incursion of 50 activists at the Forsmark plant. Greenpeace said that its non-violent actions were protests against the continuing operation of these reactors, which it says are unsafe in European stress tests, and to emphasise that stress tests did nothing to prepare against threats from outside the plant. A report by the Swedish nuclear regulator said that "the current overall level of protection against sabotage is insufficient". Although Swedish nuclear power plants have security guards, the police are responsible for emergency response. The report criticised the level of cooperation between nuclear site staff and police in the case of sabotage or attack.[18]

Photo gallery

The Barsebäck Nuclear Power Plant, which has been shut down

The Barsebäck Nuclear Power Plant, which has been shut down

See also

References

- ↑ T. Jonter: Nuclear Weapon Research in Sweden. The Co-operation Between Civilian and Military Research, 1947-1972, SKI Report 02:18

- ↑ Jonter ibid

- ↑ http://pris.iaea.org/public/, see Sweden

- ↑ Vattenfall - QuickLink

- ↑ Borgenäs, Johan (November 11, 2009). "Sweden Reverses Nuclear Phase-out Policy". Nuclear Threat Initiative.

- ↑ The Flooding Incident at the Ågesta Pressurized Heavy Water Nuclear Power Plant (pdf)

- ↑ "Neutral Sweden Quietly Keeps Nuclear Option Open", The Washington Post, 25 November 1994

- ↑ http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/gen-comm/bulletins/1996/bl96003.html

- ↑ http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-o-s/sweden.aspx

- ↑ "Sweden strikes deal to continue nuclear power". The Local. 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Centre dumps nuclear deal, The Local, 30 May 2006

- ↑ "New phase for Swedish nuclear". World Nuclear News. 18 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ Vindkraftverk möter största motståndet i Skåne, Sydsvenskan, 15 August 2005

- ↑ Swedes oppose new nuclear power: poll, The Local, 19 March 2011

- ↑ Varannan svensk vill ha nya kärnkraftverk, Dagens Nyheter, 20 January 2008

- ↑ Statistisk Årsbok 1994

- ↑ "Nuclear Energy in Sweden". World Nuclear Association. April 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ "The antis attack!". Nuclear Engineering International. 5 April 2013.

Further reading

- William D. Nordhaus, The Swedish Nuclear Dilemma — Energy and the Environment, 1997 Hardcover, ISBN 0-915707-84-5.

External links

- "Nuclear Power in Sweden". Country Briefings. World Nuclear Association (WNA). January 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- News

- 3 August 2006, BBC: Swedes shut down some nuclear reactors following testing failures