Antiquities

.jpg)

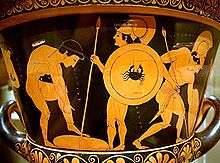

Antiquities are objects from Antiquity, especially the civilizations of the Mediterranean: the Classical antiquity of Greece and Rome, Ancient Egypt and the other Ancient Near Eastern cultures. Artifacts from earlier periods such as the Mesolithic, and other civilizations from Asia and elsewhere may also be covered by the term. The phenomenon of giving a high value to ancient artifacts is found in other cultures, notably China, where Chinese ritual bronzes, three to two thousand years old, have been avidly collected and imitated for centuries, and the Pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica, where in particular the artifacts of the earliest Olmec civilization are found reburied in significant sites of later cultures up to the Spanish Conquest.[1]

Definition

The definition of the term is not always precise, and institutional definitions such as museum "Departments of Antiquities" often cover later periods, but in normal usage Gothic objects, for example, would not now be described as antiquities, though in 1700 they might well have been, as the cut-off date for antiquities has tended to retreat since the word was first found in English in 1513. Non-artistic artifacts are now less likely to be called antiquities than in earlier periods. Francis Bacon wrote in 1605: "Antiquities are history defaced, or some remnants of history which have casually escaped the shipwreck of time".

The art trade reflects modern usage of the term; Christie's "Department of Antiquities" covers objects "from the dawn of civilization to the Dark Ages, ranging from Western Europe to the Caspian Sea, embracing the cultures of Egypt, Greece, Rome and the Near East."[2] Bonhams use a similar definition: "...4000 B.C to the 12th Century A.D. Geographically they originate from Egypt, the Near East and Europe ..." [3] Official cut-off dates are often later, being unconcerned with precise divisions of art history, and using the term for all historical periods they wish to protect: in Jordan it is 1750,[4] in Hong Kong 1800, and so on.

The term is no longer much used in formal academic discussion, because of this imprecision. Most, but not all, antiquities have been recovered by archaeology. There is little or no overlap with antiques, which covers objects, not generally discovered as a result of archaeology, at most about three hundred years old, and usually far less.

History

The sense of antiquitates, the idea that a civilization could be recovered by a systematic exploration of its relics and material culture, in the sense used by Varro and reflected in Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews was lost during the Middle Ages, when ancient objects were collected with other appeals, the rarity or strangeness of their materials or simply because they were thought to be endowed with magical or miraculous powers.[5] Precious cameos and other antique carved gems might be preserved when incorporated into crowns and diadems and liturgical objects,[6] consular ivory diptychs by being used as gospel covers. Roman columns could be re-erected in churches.[7] sarcophagi could receive new occupants and cinerary urns could function as holy water stoups. Sculptural representations of the human form, feared and reviled as "idols" could be rehabilitated by reidentifying their subjects: the equestrian bronze Marcus Aurelius of the Campidoglio was respected as a representation of the Christian emperor Constantine, and in Pavia the Regisole acquired a civic role that preserved it. In Rome the Roman bronze Spinario was admired for itself by the guidebook writer Magister Gregorius. The classicism of the Carolingian renaissance was in part inspired by appreciation of Late Antique manuscripts: the Utrecht Psalter attempts to recreate such a Late Antique original, both in its handwriting and its illustrations.[8]

Illegal trading

The export of antiquities is now heavily controlled by law in almost all countries and by the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property,[9] but a large and increasing trade in Illicit antiquities continues. The Euphronios krater is an apparent example that has come to light.[10] Another example is the ambiguous legal case concerning the Getty Museum's "Bronze Statue of a Victorious Youth".[11] The field has been further complicated by the trade in Archaeological forgeries, such as the Etruscan terracotta warriors, the Persian Princess,[12] and the Getty kouros.

See also

| Collecting |

|---|

| Terms |

| Topics |

References

- ↑ http://artworld.uea.ac.uk/cms/index.php?q=node/873. Retrieved August 10, 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Archived August 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Antiquities". Bonhams. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Roberto Weiss, 1969. The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity, p. 2ff.

- ↑ The "Cup of the Ptolemies" was set in Carolingian precious mounting and preserved in the Basilica of Saint-Denis.

- ↑ Robert Weiss notes (1969:8) that Ionic columns from the Baths of Caracalla were used in Innocent II's rebuilding of Santa Maria in Trastevere, 1139

- ↑ Noted in this context by Roberto Weiss 1969:4.

- ↑ "Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property". Unesco.org. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ↑ Brodie, Neil. "Euphronios (Sarpedon) Krater". Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ Derek Fincham, 2 March 2007

- ↑ Brodie, Neil. "Persian Mummy". Retrieved 21 August 2012.