Antun Dalmatin

| Antun Aleksandrović Dalmatin | |

|---|---|

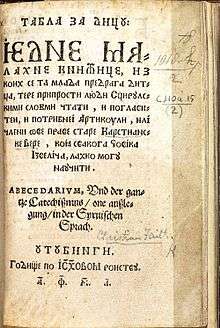

The first page of 1561 Cyrillic work "Tabla za Dicu", a translation of Primož Trubar's "Primer" by Antun Dalmatin | |

| Born | probably Senj |

| Died |

1597[1] Ljubljana[2], Habsburg Monarchy |

| Other names | Antonius Dalmata ab Alexandro |

Antun Aleksandrović Dalmatin (Latin: Antonius Dalmata ab Alexandro)[2] was 16th century translator and publisher of Protestant liturgical books.

Name and early life

Antun's surname is an exonym which means "of Dalmatia".[3] Dalmatin was probably from Senj.[4]

South Slavic Bible Institute

The South Slavic Bible Institute[5] (German: Südslawische Bibelanstalt)[6] was established in Urach (modern-day Bad Urach) in January 1561 by Baron Hans von Ungnad, who was its owner and patron.[7] Within the institute Ungnad set up a press which he referred to as "the Slovene, Croatian and Cyrillic press" (German: Windische, Chrabatische und Cirulische Trukherey).[7] The manager and supervisor of the institute was Primož Trubar.[7] The books they printed at this press were planned to be used throughout the entire territory populated by South Slavs between the Soča River, the Black Sea,[8] and Constantinople.[9] For this task, Trubar engaged Stjepan Konzul Istranin and Antun Dalmatin as translators for Croatian and Serbian.[10] The Cyrillic text was responsibility of Antun Dalmatin.[11]

Language used by Dalmatin and Istranin was based on northern-Chakavian dialect with elements of Shtokavian and Ikavian.[12] People from the institute, including Trubar, were not satisfied with translations of Dalmatin and Istranin.[12] Trubar and two of them exchanged heated correspondence about correctness of the language two of them used even before the first edition translated by Dalmatin and Istranin was published and immediately after it.[13] For long time they tried to engage certain Dimitrije Serb to help them, but without success.[14] Eventually, they managed to engage two Serbian Orthodox priests, Jovan Maleševac from Ottoman Bosnia and Matija Popović from Ottoman Serbia.[14]

References

- ↑ Posset 2013, p. 24.

- 1 2 Marković, Furunović & Radić 2000, p. 44.

- ↑ Society 1918, p. 89.

- ↑ Липатов 1987, p. 195.

- ↑ Betz 2007, p. 54.

- ↑ Vorndran 1977, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Society 1990, p. 243.

- ↑ Črnja 1978, p. 117.

- ↑ Klaić 1974, p. 71.

- ↑ Lubotsky, Schaeken & Wiedenhof 2008, p. 280.

- ↑ Društvo 1972, p. 595.

- 1 2 Mošin & Pop-Atanasov 2002, p. 18.

- ↑ štamparija 1922, p. 261.

- 1 2 Матица 1976, p. 112.

Sources

- Črnja, Zvane (1978). Kulturna povijest Hrvatske: Temelji. Otokar Keršovani.

- Society (1990). Slovene Studies: Journal of the Society for Slovene Studies. The Society.

- Lubotsky, Alexander; Schaeken, J.; Wiedenhof, Jeroen (1 January 2008). Evidence and Counter-evidence: Balto-Slavic and Indo-European linguistics. Rodopi. ISBN 90-420-2470-4.

- Posset, Franz (2013). Marcus Marulus and the Biblia Latina of 1489: An Approach to His Biblical Hermeneutics. Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar. ISBN 978-3-412-20756-4.

- Society (1918). The Bible in the World. British and Foreign Bible Society.

- Društvo (1972). Bibliotekar. Društvo bibliotekara N.R. Srbije.

- Липатов, Александр Владимирович (1987). Славианские литературы в процессе становления и развития: от древности до середины XIX века. Наука.

- Mošin, Vladimir A.; Pop-Atanasov, Ǵorgi (2002). Izbrani dela. Menora.

- Матица (1976). Review of Slavic studies. Matica srpska.

- štamparija (1922). Prilozi za književnost, jezik, istoriju i folklor. Drzhavna štamparija Kralevine srba, khrbata i slovent︠s︡a.

- Marković, Božidar; Furunović, Dragutin; Radić, Radiša (2000). Zbornik radova: kultura štampe--pouzdan vidik prošlog, sadašnjeg i budućeg : Prosveta-Niš 1925-2000. Prosveta.