Asiatic cheetah

| Asiatic cheetah | |

|---|---|

| |

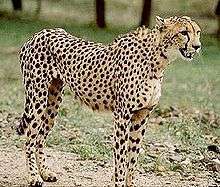

| An Asiatic cheetah in Miandasht Wildlife Refuge, Iran. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Genus: | Acinonyx |

| Species: | A. jubatus |

| Subspecies: | A. j. venaticus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Acinonyx jubatus venaticus[2] (Griffith, 1821) | |

| |

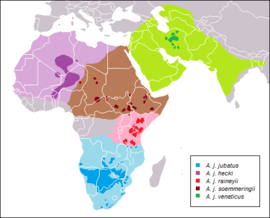

| A. j. venaticus range (green) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

A. j. venator Brookes, 1828 | |

The Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus), also known as the Iranian cheetah, is a critically endangered cheetah subspecies surviving today only in Iran.[1]

The Asiatic cheetah lives mainly in Iran's vast central desert in fragmented pieces of remaining suitable habitat. Although once common, the cheetah was driven to extinction in other parts of Southwest Asia from Arabia to India including Afghanistan. As of 2013, only 20 cheetahs were identified in Iran but some areas remained to be surveyed.[3][4] The total population is estimated to be 40 to 70 individuals, with road accidents accounting for 40% of deaths.[5][6] Efforts to stop the construction of a road through the core of the Bafq Protected Area were unsuccessful.[6] In order to raise international awareness for the conservation of the Asiatic cheetah, an illustration was used on the jerseys of the Iran national football team at the 2014 FIFA World Cup.[7] In 2015, it was estimated that approximately 50 cheetahs are living in the wild of Iran, however their numbers are rising.[8]

The Asiatic cheetah separated from its African relative between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago.[9] Along with the Eurasian lynx and the Persian leopard, it is one of three remaining species of large cats in Iran today.[10]

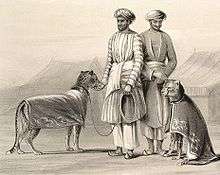

During the British colonial times in India it was called hunting leopard, a name derived from the ones that were kept in captivity in large numbers by the Indian royalty to use in hunting wild antelopes.[11] In Dutch, the cheetah is still called jachtluipaard. The Hindi word चीता cītā is derived from the Sanskrit word chitraka meaning "speckled".

Evolutionary history

The Asiatic cheetah has for a long time been classified as a cheetah subspecies. In September 2009, Stephen J. O'Brien from the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity of the National Cancer Institute argued that it is genetically identical to the African cheetah and that the populations had separated about 5,000 years ago, which is not enough time for a subspecific level differentiation.[12][13]

Results of a five-year genetic study involving DNA samples from the wild, zoos and museums in eight countries indicate that African and Asiatic cheetahs are genetically distinct. Molecular sequence comparisons suggest that they separated between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago and that subspecies level differentiation had occurred. The populations in Iran are considered the last remaining representatives of the Asian cheetah lineage.[9][14]

Characteristics

Asiatic cheetahs are slimmer, lighter and slightly shorter than their African brethren.[15] The head and body of an adult Asiatic cheetah measure from 112–135 cm (44–53 in) with a tail length between 66 and 84 cm (26 and 33 in). It weighs from 34 to 54 kg (75 to 119 lb). Males are slightly larger than the females.

The cheetah is the fastest land animal in the world.[16] It was previously thought that the body temperature of a cheetah increases during a hunt due to high metabolic activity.[17] In a short period of time during a chase, a cheetah may produce 60 times more heat than at rest, with much of the heat, produced from glycolysis, stored to possibly raise the body temperature. The claim was supported by data from experiments in which two cheetahs ran on a treadmill for minutes on end but contradicted by studies in natural settings, which indicate that body temperature stays relatively the same during a hunt. A 2013 study suggested stress hyperthermia and a slight increase in body temperature after a hunt.[18] The cheetah's nervousness after a hunt may induce stress hyperthermia, which involves high sympathetic nervous activity and raises the body temperature. After a hunt, the risk of another predator taking their kill is great and the cheetah is on high alert and stressed.[19] The increased sympathetic activity prepares the cheetah's body to run when another predator approaches. In the 2013 study, even the cheetah that did not chase the prey experienced an increase in body temperature once the prey was caught, showing increased sympathetic activity.[18]

Distribution and habitat

Cheetahs thrive in open lands, small plains, semi-desert areas, and other open habitats where prey is available. The Asiatic cheetah is found mainly in the desert areas around Dasht-e Kavir in the eastern half of Iran, including parts of the Kerman, Khorasan, Semnan, Yazd, Tehran, and Markazi provinces. Most live in five sanctuaries: Kavir National Park, Touran National Park, Bafq Protected Area, Daranjir Wildlife Reserve, and Naybandan Wildlife Reserve.[20] Remaining cheetahs are divided into widely separated populations. Some possibly survive in the dry open Balochistan province of Pakistan but locals said they had not seen it for more than fifteen years.[21]

During the 1970s, cheetahs in Iran were estimated to number about 200 individuals in seven protected areas.[22] Figures for 2005–2006 suggested between 50 and 60 cheetahs in the wild. Continuous field surveys, along with 12,000 nights of camera trapping, were used to estimate the population size. Using 80 camera traps placed throughout the Dasht-e Kavir plateau, Iranian researchers obtained images of 76 individual cheetahs over the course of ten years from 2001.[3][23] Camera traps from 2011 identified only 20 individuals in Iran but some areas were not covered.[3][4] Hooman Jowkar, director of the Conservation of Asiatic Cheetah and Its Habitat Project, stated, "the focus is just on specific protected areas; and it is not possible to conduct camera-trapping during fall and winter when cheetah is physically most active."[3] In November 2013, Morteza Eslami, the head of the Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), stated that 40 to 70 cheetahs remained.[5][6]

Former range

Asiatic cheetahs once ranged from the Arabian Peninsula to India, through Iran, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.[25] The population in Turkey was extinct already in the 19th century.[26] In Afghanistan, Asiatic cheetahs are considered extinct since the 1950s.[27]

In India, Asiatic cheetahs occurred in Rajputana, Punjab, Sind, and south of the Ganges from Bengal to the northern part of the Deccan Plateau. Asiatic cheetahs were also found in other parts of India including the Kaimur District (present-day Bihar, on eastern Uttar Pradesh border), Darrah and other desert regions of Rajasthan and parts of Gujarat and Central India.[28] Akbar the Great was introduced to cheetahs around the mid-16th century and used them for coursing blackbucks, chinkaras and antelopes. He allegedly possessed 1,000 cheetahs during his reign but this figure is exaggerated since there is neither evidence of housing facilities for so many animals, nor of facilities to provide them with sufficient meat every day.[29] By the beginning of the 20th century, wild Asiatic cheetahs were so rare in India, that between 1918 and 1945 Indian princes imported cheetahs from Africa for coursing. The last three cheetahs in India were shot by the Maharajah of Surguja in 1948. A female was sighted in the Koriya district in 1951.[24]

In Central Asia, uncontrolled hunting of Asiatic cheetahs and their prey, severe winters and conversion of grassland to areas used for agriculture contributed to the decline of cheetahs. The last reported sighting in Uzbekistan dates to the end of 1983. The last reported killed in Turkmenistan dates to November 1984.[25]

Ecology and behaviour

Females, unlike males, do not establish a territory and instead travel within their habitats, sometimes migrating long distances.[30] Photos from camera traps showed that one female migrated 130 km, a journey which included crossing a railway and two major roads.[30]

The Asiatic cheetah preys on small antelopes. In Iran, its diet consists mainly of Jebeer gazelle (also called Chinkara), Goitered gazelle, wild sheep, wild goat, and Cape hare. The main threat to the species is loss of their primary prey species due to poaching and grazing competition with domestic livestock. A study published in 2012 indicated that hares and rodents, while forming part of the cheetah's diet, are not a significant source of nutrition due to their small size and difficulty of being caught.[31]

In India, prey was formerly abundant. Before its extinction in the country, the cheetah fed on the blackbuck, the chinkara, and sometimes the chital and the nilgai.

...is in low, isolated, rocky hills, near the plains on which live antelopes, its principal prey. It also kills gazelles, nilgai, and, doubtless, occasionally deer and other animals. Instances also occur of sheep and goats being carried off by it, but it rarely molests domestic animals, and has not been known to attack men. Its mode of capturing its prey is to stalk up to within a moderate distance of between one to two hundred yards, taking advantage of inequalities of the ground, bushes, or other cover, and then to make a rush. Its speed for a short distance is remarkable far exceeding that of any other beast of prey, even of a greyhound or kangaroo-hound, for no dog can at first overtake an Indian antelope or a gazelle, either of which is quickly run down by C. jubatus, if the start does not exceed about two hundred yards. General McMaster saw a very fine hunting-leopard catch a black buck that had about that start within four hundred yards. It is probable that for a short distance the hunting-leopard is the swiftest of all mammals.— Blanford writing on the Asiatic cheetah in India quoted by Lydekker[11]

Reproduction

Evidence of mothers successfully raising cubs is very rare. In May 2013, images from a camera trap showed a mother with three cubs aged approximately one year in Miandasht Wildlife Refuge in north-east Iran.[32] In October 2013, conservationists from the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation filmed a mother with four cubs in Touran.[33] In December 2014, four cheetahs were sighted and photographed by camera traps in the Touran National Park.[34] Eleven cheetahs were also sighted at the time and another four a month later.[35] On 7 January 2015, Director General of Environmental Protection Department in North Khorasan, Iran announced a sighting of a female Asiatic cheetah and her cub at Miandasht Wildlife Refuge. Motahari also maintained that two days prior to this sighting, three other adult cheetahs were sighted by the locals some kilometers to the eastern border of Miandasht, and immediately reported to Jajrom Department of Environment.[36] In July 2015, eight new cheetahs (five adults and three cubs) were spotted at Khar Touran.[37]

Whilst it is estimated that 50 to 70 individuals are living in the wild, the numbers of Asiatic cheetah are stated to be on the rise.[8] In December 2015, it is reported that 18 new Asiatic cheetah cubs had recently been born and it was hoped for two captive Asian cheetahs at Pardisan Park would produce cubs.[38]

Threats

Reduced gazelle numbers, persecution, land-use change, habitat degradation and fragmentation, and desertification contributed to the cheetah's decline.[22] According to the Iranian Department of Environment this degradation occurred mainly between 1988 and 1991. The cheetah is affected by loss of prey as a result of overgrazing from introduced livestock and antelope hunting. Its prey was pushed out as herders entered game reserves with their herds.[31] In some areas, cheetahs compete for gazelles with poachers on powerful motorcycles; the gazelle population in the Kalmand reserve fell from about 2,000 to 200 within a few years.[39]

Mining development and road construction near reserves also threaten the population.[22] Coal, copper, and iron have been mined in the cheetah's habitat in three different regions in central and eastern Iran. It is estimated that the two regions for coal (Nayband) and iron (Bafq) have the largest cheetah population outside the protected areas. Mining itself is not a direct threat to cheetahs; road construction and the resulting traffic have made the cheetah accessible to humans, including poachers. The Iranian border regions to Afghanistan and Pakistan (Baluchistan province) are major passages for armed outlaws and opium smugglers who are active in the central and western regions of Iran, passing through cheetah habitat. According to Asada in 1997, the region suffers from uncontrolled hunting throughout the desert and the governments of the three countries cannot establish control.[22] There is no reliable information regarding the present situation in this region.

Presently, there are between 40 and 70 Asiatic cheetahs in Iran. Morteza Eslami, head of the Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), told Trend News Agency in November 2013 that its survival remained unsecured.[6] In 2012–13, two-thirds of cheetah deaths were the result of road accidents.[6][40] Efforts to stop the construction of a road through the core of the Bafq Protected Area were unsuccessful.[6] In February 2015, it was reported that road accidents were responsible for 40% of deaths.[5]

In addition, some herders are accompanied by large mastiff-type dogs into protected areas. These dogs killed five cheetahs between 2013 and 2016.[39]

On 30 August 2016, it was reported that there are fewer than 40 Asiatic cheetahs and the population of female cheetahs may have been reduced to two in the wild.[41] However, the report was later denied on 4 September 2016.[42]

Conservation efforts

The Asiatic cheetah is now listed as critically endangered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, wildlife conservation was given a lower priority,[43] but in recent years Iran has made efforts to conserve the remaining population. Iran's Department of the Environment, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) have launched the Conservation of the Asiatic Cheetah Project (CACP) designed to preserve and rehabilitate the remaining areas of cheetah habitat left in Iran.[44] Some surveys by Asadi in the latter half of 1997 showed that urgent action was required to rehabilitate wildlife populations, especially gazelles and their habitat, if the Asiatic cheetah is to survive.

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the Department of Environment, Iran (DoE) began a collaring project for Asiatic cheetahs in the fall of 2006.[45][46] GPS collars provide data on the cat's movements.[47] International sanctions have made some projects, such as obtaining camera traps, difficult.[33]

A few orphaned cubs have been raised in captivity, such as Marita who died at the age of nine years in 2003. Beginning in 2006, the day of his death,[48] 30 August, became the Cheetah Conservation Day, used to inform the public about conservation programs.[47][49] A cheetah appeared on the jerseys of the Iran national football team at the 2014 FIFA World Cup, after receiving approval from FIFA.[7][50] In May 2015, the Department of the Environment announced plans to quintuple the penalty for poaching a cheetah to 100 million tomans (about $30,000).[51]

Iranian officials have discussed constructing wildlife crossings to reduce the number of deaths in traffic accidents.[48]

Projects

Training course for herders: It was estimated that ten cheetahs live in the Bafq Protected Area. According to the Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), herders are considered as a significant target group which generally confuses the cheetah with other similar-sized carnivores, including wolf, leopard, striped hyena, and even caracal and wild cat. On the basis of the results of conflict assessment, a specific Herders Training Course was developed in 2007, in which they learned how to identify the cheetah as well as other carnivores, since these were the main causes for livestock kills. These courses were a result of cooperation between UNDP/GEF, Iran’s Department of Environment, ICS, and the councils of five main villages in this region.

Cheetah Friends: Another incentive in the region is the formation of young core groups of Cheetah Friends, who after a short instructive course, are able to educate people and organize cheetah events and become an informational instance in cheetah matters for a number of villages. Young people have expressed growing interest in the issue of cheetah and other wildlife conservation.

Ex-situ conservation: India, where the Asiatic cheetah is now extinct, is interested in cloning the cheetah to reintroduce it to the country.[52] It was claimed that Iran – the donor country – was willing to participate in the project.[53] Later, however, Iran refused to send a male and female cheetah or to allow experts to collect tissue samples from a cheetah kept in a zoo there.[54] In 2009, the Indian government considered reintroducing cheetahs through importing from Africa through captive breeding.[55]

In 2014, an Asiatic cheetah was cloned for the first time by scientists from the University of Buenos Aires.[56] The embryo was not born.[57]

Semi-captive breeding

In February 2010, Mehr News Agency, Payvand Iran News released the photos of an Asiatic/Iranian cheetah in a seemingly large compound within natural habitat enclosed by chain link fence, this location was reported in this news article to be the "Semi-Captive Breeding and Research Center of Iranian Cheetah" in Iran's Semnan province. The Asiatic cheetah pictured had a winter coat with longer fur.[58] Another news report stated that the centre is home to about ten Asiatic cheetahs in a semi-wild environment protected by wire fencing all around.[59]

Wildlife officials in Miandasht Wildlife Refuge and the Turan National Park have raised a few orphaned cubs.[47][60] In May 2014, officials said they would bring together a pair of grown individuals in the hope they would produce cubs, while acknowledging that cheetahs are difficult to breed.[60]

In March 2015, a pair of adult male and female Asiatic cheetahs are part of a captive breeding project somewhere close to the Milad tower in Tehran for the first time.[61]

Re-introduction proposals

India

Cheetahs have been known to exist in India for a very long time but hunting and other factors led to their extinction in the country in the 1940s. The Indian government planned a re-wilding project for cheetahs where they would be bred in captivity before being released into the wild. Then Minister of Environment and Forests, Jairam Ramesh, told the Rajya Sabha on 7 July 2009 that, "The cheetah is the only animal that has been described extinct in India in the last 100 years. We have to get them from abroad to repopulate the species." He was responding to a calling attention notice from Rajiv Pratap Rudy of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). "The plan to bring back the Cheetah which fell to indiscriminate hunting and complex factors like a fragile breeding pattern is audacious given the problems besetting tiger conservation." Two naturalists, Divya Bhanusinh and MK Ranjit Singh, suggested the idea of importing the South African cheetahs from Namibia. According to the plan, they would be bred in captivity in India and eventually released into the wild.

In September 2009, at a cheetah reintroduction workshop organized in India, Stephen J. O'Brien asserted that the African and Asiatic cheetahs were genetically identical and had separated only 5,000 years ago. Cheetah expert Laurie Marker of the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) and other wildlife experts advised the Indian Government that for reintroduction purposes, India should source the cheetah from Africa where they were much more numerous instead of trying to have some removed from the critically endangered low population in Iran. Participants included India's Union Minister of State for Environment and Forests, Jairam Ramesh, chief wildlife wardens of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, officials of the environment ministry, cheetah experts from across the globe, representatives from the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) including Yadvendradev Jhala, and IUCN, an international conservation NGO. The conference was organized by the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI).[12][13] In May 2012, India's Supreme Court suspended attempts to introduce African cheetahs following the publication of newer genetic evidence, which suggests that the Asian and African cheetahs separated between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago.[62]

In popular culture

In 2014, the Iranian national football team announced that their 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2015 AFC Asian Cup kits are imprinted with pictures of the Asiatic cheetah in order to bring attention to conservation efforts.[63] In February 2015, Iran launched a search engine, Yooz, that features a cheetah logo.[64]

In September 2015 Meraj Airlines introduced the new livery of Iranian Cheetah to support its conservation efforts.[65]

See also

- American cheetahs (Miracinonyx)

- Northwest African cheetah

References

- 1 2 Jowkar, H.; Hunter, L.; Ziaie, H.; Marker, L.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C. & Durant, S. (2008). "Acinonyx jubatus ssp. venaticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 532. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 4 Khosravifard, Sam (29 March 2013). "How Many Asiatic Cheetahs Roam across Iran?". Scientific American.

- 1 2 "Just 20 individual cheetahs identified in Iran so far, including 6 surviving females". Wildlife Extra. March 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Iranian Cheetah's dwindling numbers lower than thought". Payvand. 15 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Niayesh, Umid (8 November 2013). "Iranian Cheetahs remain endangered – expert (PHOTO) (VIDEO)". trend.az.

- 1 2 "FIFA confirms depiction of Asiatic Cheetah on Iran jersey". Persian Football. 1 February 2014.

- 1 2 "UNDP Iran releases Asiatic Cheetah PSA". ir.undp.org. 15 Jun 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- 1 2 Charruau, P.; Fernandes, C.; Orozco-Terwengel, P.; Peters, J.; Hunter, L.; Ziaie, H.; Jourabchian, A.; Jowkar, H.; Schaller, G.; Ostrowski, S. (2011). "Phylogeography, genetic structure and population divergence time of cheetahs in Africa and Asia: evidence for long-term geographic isolates". Molecular Ecology. 20 (4): 706–724. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04986.x. PMC 3531615

. PMID 21214655.

. PMID 21214655. - ↑ "United Nation Development Program UNDP" (PDF).

- 1 2 Lydekker, R. A. (1894), The Royal Natural History, 1, Frederick Warne & Company, London, New York

- 1 2 "Experts eye African cheetahs for reintroduction, to submit plan". IANS. Thaindian. 10 September 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- 1 2 "Workshop on cheetah relocation begins, views differ". PTI. Times of India. 9 September 2009. Retrieved 29 Jan 2011.

- ↑ Weise, E. (2011). "Three distinct cheetah populations, but Iran's on the brink". USA Today.

- ↑ King, Anthony (14 May 2015). "Can the Iranian cheetah outrun extinction?". Irish Times.

- ↑ Hildebrand, M. (1959), Motions of the running cheetah and horse, Journal of Mammalogy 40 (4), pp. 481–495

- ↑ Taylor, C. R.; Rowtree, V. J. (1973), Temperature regulation and heat balance in running cheetahs: a strategy for sprinters?, American Journal of Physiology 224, pp. 848–852

- 1 2 Hetem, R.; Mitchell, D.; de Witt, B. A.; Fick, L. G.; Meyer, L. C. R.; Maloney, S. K.; Fuller, A. (2013), Cheetah do not abandon hunts because they overheat, Biology Letters 9: 1–5

- ↑ Phillips, J. A. (1993), Bone consumption by cheetahs at undisturbed kills: evidence for a lack of focal-palatine erosion, Journal of Mammalogy 74, pp. 487–492

- ↑ Farhadinia, M.S. (2004). "The last stronghold: cheetah in Iran" (PDF). Cat News. 40: 11–14.

- ↑ "Asiatic cheetah". felidae.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 Asadi, H. (1997). "The environmental limitations and future of the Asiatic cheetah in Iran. Unpublished project progress report" (PDF). IUCN Iran.

- ↑ Smith, Roff (November 2012). "Cheetahs on the Edge". National Geographic.

- 1 2 Divyabhanusinh (1999), The End of a Trail: the Cheetah in India, Banyan Books, New Delhi

- 1 2 Mallon, D. P. (2007). "Cheetahs in Central Asia: A historical summary" (PDF). Cat News 46: 4–7.

- ↑ Kryštufek, B. and V. Vohralík. (2001). Mammals of Turkey and Cyprus: Introduction, Checklist, Insectivora. Knjižnica Annales Majora, Koper, Republic of Slovenia.

- ↑ Habibi, K. (2003), "Mammals of Afghanistan", Zoo Outreach Organisation, USFWS, Coimbatore, India

- ↑ Pocock, R. I. (1939). The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. Taylor and Francis, London.

- ↑ Thapar, V.; Thapar, R.; Ansari, Y. (2013). Exotic Aliens: The Lion and the Cheetah in India. Aleph Book Company, New Delhi.

- 1 2 "Cheetah in Iran migrating between 2 reserves 130 kilometres apart". Wildlife Extra. June 2012.

- 1 2 Bardo, Matt (26 September 2012). "Asiatic cheetahs forced to hunt livestock". BBC News.

- ↑ "Cheetah family still thriving in Iran – All three cubs have reached 1 year old". Wildlife Extra. May 2013.

- 1 2 Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (23 October 2013). "Cheetahs' Iranian revival cheers conservationists". TheGuardian.com.

- ↑ "Camera traps capture 4 new Asiatic Cheetahs in Iran". Mehr News Agency. 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Female Asiatic cheetah, 3 cubs sighted in Turan National Park". mehrnews.com. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ↑ "Female Asiatic Cheetah, cub sighted in Miandasht". Mehr News Agency. 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "8 Asiatic cheetahs spotted in Shahroud". mehrnews.com. 3 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "Asiatic cheetah extinction trend reversed". Payvand Iran News. 7 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- 1 2 Croke, Vicki (24 March 2016). "Saving The Desert Cheetahs Of Iran". WBUR.

- ↑ "Fifth Iranian cheetah dies in less than a month". Trend News Agency. 27 December 2013.

- ↑ Saeed Kamali Dehghan (30 August 2016). "Two female Asiatic cheetahs remain in wild in Iran, say conservationists". theguardian.com. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ "Asiatic cheetah extinction claim categorically denied". Tehran Times. 4 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ "Cheetahs in Iran; the last stronghold of the Asiatic cheetah". Wildlife Extra. Archived from the original on 15 November 2009.

- ↑ "Conservation of the Asiatic Cheetah Project" (PDF). IUCN.

- ↑ "Studies of the Asiatic Cheetah in Iran". Saving Wild Places. Archived from the original on 3 July 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ↑ "Iran Cheetah Project". Wildlife Conservation Society, New York. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- 1 2 3 Karimi, Nasser (26 June 2014). "Iran tries to save Asiatic cheetah from extinction". Associated Press.

- 1 2 Mostaghim, Ramin; Bengali, Shashank (29 September 2016). "The world's fastest animal is in a race for survival in Iran". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Rohani, Bijan (3 September 2013). "Iranian Cheetah Conservation Day". Payvand.

- ↑ "FIFA chief green-lights Iranian cheetah logo for Iran team jersey". Tehran Times. 9 November 2013. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013.

- ↑ "Iran multiplies fines for poachers". Tehran Times. 25 May 2015.

- ↑ Pros and Cons of inbreeding – See footnotes on page

- ↑ Singh, L. (2003). Project to Clone Extinct Cheetah Gets a Boost. www.cabi.org

- ↑ "Mullas' regime says "No" to cloning of cheetah". 9 July 2005. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007.

- ↑ "Extinct in India, Cheetah may be imported". The Times Of India. 8 July 2009.

- ↑ Moro, L. N., Veraguas, D., Rodriguez-Alvarez, L., Hiriart, M. I., Buemo, C., Sestelo, A., & Salamone, D. (2015). 212 Interspecific Clonong and Embryo Aggregation influence the Expression of oct4, nanog, sox2, andcdx2 in Cheetah and Domestic Cat Blastocysts. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 27(1): 196–196.

- ↑ Xiang, B. (2015). Argentine scientists clone endangered Asiatic Cheetahs for first time. Xinhua, english.news.cn

- ↑ "Photos: Saving the Iranian Cheetah from Extinction; Photos by Yuness Khani". Mehr News Agency. Payvand Iran News. 10 February 2010.

- ↑ "Asiatic Cheetah on The Brink of Extinction – Less Than one Hundred Asiatic Cheetahs Survive in the World". Hamsayeh.net. 27 February 2010.

- 1 2 Gaeini, Mohamad; Habibinia, Omid (14 May 2014). "Courting endangered cheetahs capture Iranian hearts". France24.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014.

- ↑ "Two endangered cheetahs in Tehran for conservation project". PressTV.ir. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "India court suspends plan to reintroduce cheetah". BBC News. 9 May 2012.

- ↑ "Iran's World Cup kits unveiled Photos". Persian Football. 1 February 2014.

- ↑ Sridharan, Vasudevan (16 February 2015). "Iran launches own search engine Yooz to beat internet-related sanctions". International Business Times.

- ↑ "Efforts to save the Iranian cheetah take off!". euronews.com. 18 September 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acinonyx jubatus venaticus. |

- Species portrait Asiatic cheetah; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

- Iranian Cheetah Society – A non-profit organisation set up to save the Asiatic cheetah.

- Asiatic Cheetah Project – Felidae Conservation Fund, USA

- Cheetah Conservation Fund

- Iran Department of Environment

- Video: Hunting with Cheetahs in India on YouTube

- Video: 'Cheetahs in Iran', the last stronghold of the Asiatic cheetah on YouTube.

- Video: Extinctions : Discover the endangered Asiatic cheetah on YouTube.

- ScienceDaily 2011: The Need for Conservation of Asiatic Cheetahs