Astrapotheria

| Astrapotheria Temporal range: Late Paleocene–Late Miocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction of Astrapotherium in natural habitat | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Subclass: | Theria |

| Infraclass: | Eutheria |

| Superorder: | †Meridiungulata |

| Order: | †Astrapotheria Lydekker 1894[1] |

| Families | |

|

†Astrapotheriidae | |

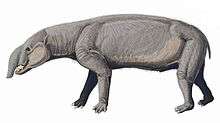

Astrapotheria is an extinct order of South American and Antarctic hoofed mammals that existed from the Late Paleocene (Itaboraian SALMA) to the Middle Miocene (Laventan SALMA), 59 to 12 million years ago.[2] Astrapotheres were large and rhinoceros-like animals and are certainly one of the most bizarre orders of mammals with an enigmatic evolutionary history.[3]

The history of this order is enigmatic, but it may taxonomically belong to Meridiungulata (along with Notoungulata, Litopterna and Pyrotheria). In turn, Meridungulata is believed to belong to the extant superorder Laurasiatheria. However, some scientists regard the astrapotheres (and sometimes the Meridiungulata all together) to be members of the clade Atlantogenata. An example of this order is Astrapotherium magnum. When alive, Astrapotherium might have resembled a mastodon, but was only three meters (ten feet) long.

Description

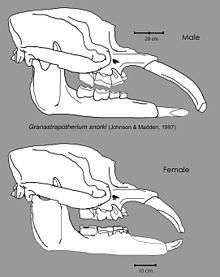

Their lophodont molars and tusk-like canines became extremely large and ever-growing in later astrapotheres. The upper molars lack an ectocingulum and are dominated by well-developed ectoloph and protoloph. Additional lophs formed in some derived taxa. They had lower molars with two cross-lophs, including a high protocristid, and eventually became almost selenodont. As a result, their dentition is similar to notoungulates, but it seems to have evolved independently. The cheek teeth are similar to rhinocerotoids, including similar microstructure, which indicate they had the same function.[3]

Postcranially, astrapotheres are relatively robust and more or less graviportal but have slender long bones, most notably in the hindlegs, suggesting they were amphibious. In order to support their proboscises and large heads they had relatively long and massive necks in relation to the rest of the vertebral column. Their feet are pentadactyl with short and stout podial and metapodial bones. Most characteristic for the order are the flat astragalus, equipped with a short neck and a flat head, articulating with both the navicular and cuboid bones; and their calcaneus with its enlarged peroneal tubercle.[3]

Three families are recognized: Eoastrapostylopidae from the late Paleocene, Trigonostylopidae from the Paleocene-Eocene, and Astrapotheriidae from the Eocene-Miocene. The Brazilian, Itaboraian Tetragonostylops and the Argentinian, Riochican Eoastrapostylops are the oldest astrapotheres. The latter, with its low-crowned and lophoselenodont cheek teeth, is considered the most primitive astrapothere. Trigonostylopids are distinct from other astrapotheres in their ear anatomy but are included in the order because of otherwise similar characters. Trigonostylops is one of few eutherian taxa found in Antarctica.[3]

The most famous member of the order is undoubtedly Astrapotherium, a 3 m (9.8 ft) long elephant-like beast that had lost its upper incisors and developed ever-growing canine tusks. They had lost their anterior premolars, resulting in a gap between their tusks and the hypsodont cheek teeth. The short and retracted nasal bones indicate a moderately developed proboscis. The small Eocene Trigonostylops lacked such retracted nasals and probably also a proboscis. Other astrapotheriids, such as the Casamayoran Scaglia and Albertogaudrya, were between a sheep and a tapir in size and already the largest South American mammals.[3]

Classification

There is no scientific consensus regarding the classification within Astrapotheria. For example, Paula Couto 1963 originally described Tetragonostylops as a trigonostylopid but Soria 1982 and 1984 transferred the genus to Astrapotheriidae and concluded that the remaining two genera in that family, Trigonostylops and Shecenia, form a basal collateral branch within Astrapotheriidae. According to Cifelli 1993, Trigonostylopidae (including Eoastrapostylopidae) is the stem group of Astrapotheriidae.[4]

- Astrapotheriidae Ameghino 1887[5]

- Albertogaudrya Ameghino 1901[5]

- Antarctodon Bond et al. 2011[6]

- Astrapodon Ameghino 1891

- Astraponotus Ameghino 1901[5]

- Astrapothericulus Ameghino 1901[5]

- Astrapotherium Burmeister 1879[5]

- Comahuetherium Kramarz & Bond 2011

- Granastrapotherium Johnson & Madden 1997

- Liarthrus Ameghino 1897[5]

- Maddenia Kramarz & Bond 2009

- Parastrapotherium Ameghino 1895[5]

- Scaglia Simpson 1957

- Uruguaytherium Kraglievich 1928

- Xenastrapotherium Kraglievich 1928[5]

- Eoastrapostylopidae Soria & Powell 1981[7]

- Eoastrapostylops Soria & Powell 1981

- Trigonostylopidae Ameghino 1901[5]

- Shecenia Simpson 1935

- Tetragonostylops Paula Couto 1963

- Trigonostylops Ameghino 1897[5]

Notes

| Wikispecies has information related to: Astrapotheria |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Astrapotheria. |

- ↑ Astrapotheria in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved March 2013

- ↑ "The uruguaytheriine Astrapotheriidae from the rich middle Miocene Honda Group of the upper Magdalena River valley in Colombia (...) are the youngest securely dated remains of that order in South America." Johnson & Madden 1997, p. 356

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rose 2006, pp. 235–6

- ↑ Bond et al. 2011, Relationships

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Classification of the order Astrapotheria in the Paleobiology Database. Retrieved March 2013.

- ↑ "Phylogenetic analysis suggests that Antarctodon is closer to genera classified by previous authors as astrapotheriids (e.g., Albertogaudrya and Tetragonostylops) than it is to Trigonostylops." Bond et al. 2011, p. 2

- ↑ "Name — Eoastrapostylopidae Soria & Powell 1981". Index to Organism Names. Retrieved March 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

References

- Ameghino, Florentino (1887). Apuntes preliminares sobre algunos mamíferos estinguidos del yacimiento de "Monte Hermoso" existentes en el "Mueso La Plata". Buenos Aires. OCLC 39794328.

- Ameghino, Florentino (1891). Los monos fósiles del Eoceno de la República Argentina (PDF). Revista Argentina de Historia Natural. 1. Buenos Aires. pp. 383–397. Retrieved March 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Ameghino, Florentino (1895). Première contribution à la connaissance de la faune mammalogique des couches à Pyrotherium. Buenos Aires: P.E. Coni.

- Ameghino, Florentino (1897). "Mamiferos Cretaceos de la Argentina. Segunda contribucion al conocimiento de la fauna mastologica de las capas con restos de Pyrotherium". Boletin Instituto Geografico Argentino. 18: 406–521.

- Ameghino, Florentino (1901). "Notices préliminaires sur des ongulés des terrains Crétacés de Patagonie". Boletín de la Academia de Ciencias en Córdoba. 16: 349–426. OCLC 123174974.

- Bond, Mariano; Kramarz, Alejandro; Macphee, Ross D. E.; Reguero, Marcelo (June 2011). "A New Astrapothere (Mammalia, Meridiungulata) from La Meseta Formation, Seymour (Marambio) Island, and a Reassessment of Previous Records of Antarctic Astrapotheres" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 3718: 1–16. doi:10.1206/3718.2. OCLC 728156717. Retrieved March 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Burmeister, Hermann (1879). Description physique de la République Argentine : d'après des observations personnelles et étrangères. 3 Animaux vertébrés, 1. partie, Mammifères vivants et éteints. Paris: Savy. p. 520. OCLC 162707154.

- Cifelli, R. L. (1993). "The phylogeny of the native South American ungulates". In Szalay, F.S.; Novacek, M.J.; McKenna, M.C. Mammal phylogeny. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 195–216. ISBN 9780387978536.

- Johnson, Steven C.; Madden, Richard H. (1997). "Uruguaytheriine Astrapotheres of Tropical South America". In Kay, Richard F.; Madden, Richard H.; Cifelli, Richard L.; Flynn, John J. Vertebrate paleontology in the neotropics : the Miocene fauna of La Venta, Colombia. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 355–82. ISBN 9781560984184. OCLC 30320084.

- Kraglievich, Lucas (1928). Sobre el supuesto Astrapotherium Christi Stehlin, descubierto en Venezuela (Xenastrapotherium n. gen.) y sus relaciones con Astrapotherium magnum y Uruguaytherium Beaulieui. Buenos Aires: La Editorial Franco-Argentina. OCLC 20881142.

- Kramarz, Alejandro G; Bond, Mariano (2009). "A new oligocene astrapothere (Mammalia , Meridiungulata) from Patagonia and a new appraisal of astrapothere phylogeny". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 7 (1): 117–128. doi:10.1017/S147720190800268X.

- Kramarz, Alejandro; Bond, Mariano (2011). "A new early Miocene astrapotheriid (Mammalia, Astrapotheria) from Northern Patagonia, Argentina". Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie u. Palaontologie / Abhandlungen. 260 (3): 277–87. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2011/0132. OCLC 740850188.

- Lydekker, Richard (1894). "Contributions to a knowledge of the Fossil Vertebrates of Argentina. III — A study of extinct argentine ungulates". Anales del Museo de La Plata. Paleontología Argentina. 2 (3): 1–86. OCLC 12322584.

- Paula Couto, Carlos, de (1963). "Um Trigonostylopidae do Paleoceno do Brasil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 35 (3): 339–51.

- Paula Couto, Carlos, de (1976). "Fossil mammals from the cenozoic of Acre, Brazil". Porto Alegre: Museu de Ciências naturais da Fundação zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul. OCLC 31145316.

- Rose, Kenneth David (2006). The beginning of the age of mammals. Baltimore: JHU Press. ISBN 0801884721.

- Simpson, George Gaylord (1935). "Descriptions of the oldest known South American mammals, from the Rio Chico Formation" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 793: 1–25. OCLC 44083494. Retrieved March 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Simpson, George Gaylord (1957). "A new Casamayoran astrapothere". Revista del Museo Municipal de Ciencias Naturales y Tradicional de Mar del Plata. 1 (3): 11–18. OCLC 81633287.

- Soria, M. F.; Powell, J. E. (1981). "Un primitivo Astrapotheria (Mammalia) y la edad de la Formacion Rio Loro, Provincia de Tucuman, Republica Argentina". Ameghiniana. 18 (3–4): 155–68.

- Soria, M. F. (1982). "Tetragonostylops apthomasi (Price y Paula Couto, 1950): su asignación a Astrapotheriidae (Mammalia; Astrapotheria)". Ameghiniana. 19 (3–4): 234–238.

- Soria, M. F. (1984). "Eoastrapostylopidae: diagnosis e implicaciones en la sistemática y evolución de los Astrapotheria preoligocénicos". Actas 2° Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía: 175–182.