Asturian miners' strike of 1934

| Asturian miners' strike of 1934 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

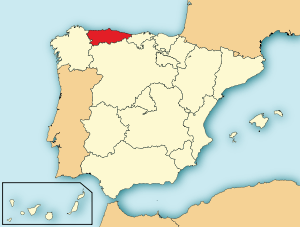

Location of Asturias within Spain | |||

| Date | 4 – 19 October 1934 | ||

| Location | Asturias, Spain | ||

| Causes | Asturian miners strike | ||

| Result | Strike suppressed | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

|

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| |||

The Asturian miners' strike of 1934 was a major strike action, against the entry of the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA) into the Spanish government on October 6,[1] which took place in Asturias in northern Spain, that developed into a revolutionary uprising. It was crushed by the Spanish Navy and the Spanish Republican Army, the latter using mainly Moorish troops from Spanish Morocco.[2]

Francisco Franco controlled the movement of the troops, aircraft, warships and armoured trains used in the crushing of the revolution. Visiting Oviedo after the rebellion had been put down he said; "this war is a frontier war and its fronts are socialism, communism and whatever attacks civilization in order to replace it with barbarism."[3] Though the forces sent to the north by Franco consisted of the Spanish Foreign Legion and the Moroccan colonial troops known as Regulares, the right-wing press portrayed the Asturian rebels in xenophobic and anti-Semitic terms as the lackeys of a foreign Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy.[4]

Background

Following the victory of the parties of the right in the general election of 1933, the new government, led by Alejandro Lerroux, met stiff resistance from the leftist parties. As a result, the anarchists and communists called a general strike. However the strike immediately exposed differences on the left between the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) linked Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), which organised the strike and the anarcho-syndicalist trade union, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), which was sceptical of the value of strike action as a political tactic. As a result, the strike failed in much of Spain. A "Catalan republic" lasted just ten hours, and despite an attempt at a general stoppage in Madrid, other strikes did not endure and Asturias was left to fight alone.[5]

The strike

In several mining towns in Asturias, local unions gathered small arms and were determined to see the strike through. The strike began on the evening of October 4, with the miners occupying several towns, attacking and seizing local Civil and Assault Guard barracks.[6] The following day saw columns of miners advancing along the road to Oviedo, the provincial capital. With the exception of two barracks where fighting with the garrison of 1,500 government troops continued, the city was taken by October 6. The miners proceeded to occupy several other towns, most notably the large industrial centre of La Felguera, and set up town assemblies or 'revolutionary committees', to govern towns they controlled.[7]

The revolutionary soviets set up by the miners attempted to impose order on the areas under their control and the moderate socialist leadership of Ramón González Peña and Balamino Tomas took measures to restrain violence. However a number of captured priests, businessmen and civil guards were executed in Turon and Sama, while churches, convents and part of the university at Oviedo were destroyed.[8]

The government in Madrid now called on two of its senior generals Manuel Goded and Francisco Franco to co-ordinate suppression of what had become a major rebellion. Goded and Franco recommended that regular units of colonial troops from Spanish Morocco be used instead of the inexperienced conscripts of the Peninsular Army. The Minister of War Diego Hidalgo agreed that the latter would be at a disadvantage in combat against the well organized miners, who were skilled in the use of dynamite.

Columns of Civil Guards, Moroccan Regulares and the Spanish Legion were accordingly organized under General Eduardo López Ochoa and Colonel Juan de Yague to relieve the besieged government garrisons and to retake the towns from the miners. These troops were carried on the CNT-controlled railways to Asturias without resistance by the anarchists. During the operations, an autogyro made a reconnaissance flight for the government troops, in what was the first military employment of a rotorcraft.[9] On October 7, delegates from the anarchist-controlled seaport towns of Gijón and Avilés arrived in Oviedo to request weapons to defend against a landing of government troops. Ignored by the socialist UGT-controlled committee, the delegates returned to their town empty-handed and government troops met little resistance as they recaptured Gijón and Avilés the following day.[10] The capture of the two key ports effectively spelled the end of the strike.

Aftermath

In the armed action taken against the uprising, some 3,000 miners were killed in the fighting, with another 30,000[11]–40,000 taken prisoner,[12] and thousands more sacked from their jobs.[13] The repression of the uprising carried out by the colonial troops was very harsh, including looting, rape and summary executions.[14][15] According to Hugh Thomas, 2,000 persons died in the uprising: 230-260 military and police, 33 priests, 1,500 miners in combat and 200 individuals killed in the repression (among them the journalist Luis de Sirval, who pointed out tortures and executions and was arrested and killed by three officers of the Legion).[11] The government suspended Constitutional guarantees. Almost all the left's newspapers were closed, as they were owned by the parties which promoted the uprising. Hundreds of town councils[16] and mixed juries were suspended. Torture in prisons was widespread, as it was during all the Republic's lifetime.[17]

Franco was convinced that the workers uprising had been "carefully prepared by the agents of Moscow". Fed by material he gathered from the Entente Anticommuniste of Geneva, Franco believed that he was justified in the brutal use of troops against Spanish civilians. Historian Paul Preston: "Unmoved by the fact that the central symbol of rightist values was the reconquest of Spain from the Moors, Franco did not hesitate to ship Moorish mercenaries to fight in Asturias, the only part of Spain where the crescent had never flown. He saw no contradiction about using the Moors, because he regarded left-wing workers with the same racialist contempt he possessed towards the tribesmen of the Rif."[18]

References

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p.61, University of Notre Dame Press, 2010

- ↑ The Splintering of Spain, p.54 CUP, 2005

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p.62

- ↑ Sebastian Balfour, Deadly Embrace:Morocco and the Road to the Spanish Civil War, 252-254 OUP 2002

- ↑ Spain 1833-2002, p.133, Mary Vincent, Oxford, 2007

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War,1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. pp.154-155

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001. London. p.131

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh, p132 The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001, ISBN 0-141-01161-0

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G. (1993). Spain's first democracy: the Second Republic, 1931–1936. Univ of Wisconsin Press, p. 219. ISBN 0-299-13674-4

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War,1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p.157

- 1 2 Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001. London. p.136

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p.161

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. 2006. London. p.32

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. 2006. London. pp.31-32

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. pp.159-160

- ↑ Graham, Helen. The Spanish Civil War. A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. 2005. p.16

- ↑ Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War,1931-1939. Princeton University Press. Princeton. 1967. p.160

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy, pp61-62

Bibliography

- Beevor, Antony. The battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Penguin Books. 2006. London.

- García Gómez, Emilio. Asturias 1934. Historia de una tragedia. Pórtico. 2010. Zaragoza.

- Graham, Helen. The Spanish Civil War. A very short introduction. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Jackson, Gabriel. The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931–1939. Princeton University Press, 1967. Princeton.

- Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. 2001. London. ISBN 978-0-14-101161-5

External links

- 1934: The Asturias Revolt at libcom.org

- Republican Spain at countrystudies.us

- Documents on the strike and its aftermath from "Trabajadores: The Spanish Civil War through the eyes of organised labour", a digitised collection of more than 13,000 pages of documents from the archives of the British Trades Union Congress held in the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick