Atrocities in the Congo Free State

_(14793501603).jpg)

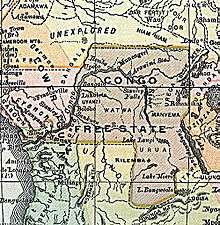

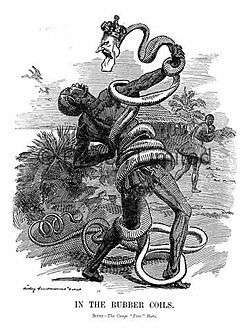

In the period from 1885 to 1908, a number of well-documented atrocities were perpetrated in the Congo Free State (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo) which, at the time, was a colony under the personal rule of King Leopold II of Belgium. These atrocities were sometimes collectively referred to by European contemporaries as the "Congo Horrors", and were particularly associated with the labour policies used to collect natural rubber for export. Together with epidemic disease and a falling birth rate, these atrocities contributed to a sharp decline in the population. The magnitude of the population fall over the period is disputed, but it is thought to range from one to 15 million.

After the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, the European powers allocated the Congo Basin region to a private charitable organisation run by Leopold II, who had long held ambitions for colonial expansion. The territory under Leopold's control exceeded 1,000,000 square miles (2,600,000 km2) and, amid financial problems, was ruled by a tiny cadre of white administrators drawn from across Europe. Initially, the colony proved unprofitable and insufficient with the state always close to bankruptcy. The boom in demand for natural rubber, which was abundant in the territory, created a radical shift in the 1890s—to facilitate the extraction and export of rubber, all "uninhabited" land in the Congo was nationalised, with the majority distributed to private companies as concessions. Some was kept by the state. Between 1891 and 1906, the companies were allowed to do whatever they wished with almost no judicial interference, the result being that forced labour and violent coercion were used to collect the rubber cheaply and maximise profit. A native paramilitary army, the Force Publique, was also created to enforce the labour policies. Individual workers who refused to participate in rubber collection could be killed and entire villages razed. Individual white administrators were also free to indulge their own sadism.

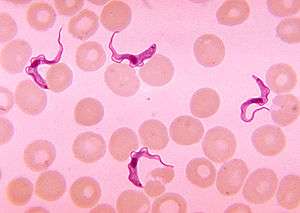

Despite these atrocities, the main cause of the population decline was disease. A number of pandemics, notably African sleeping sickness, smallpox, swine influenza and amoebic dysentery, ravaged indigenous populations. In 1901 alone it was estimated that half-a-million Congolese had died from sleeping sickness. Disease, famine and violence combined to reduce the birth-rate while excess deaths rose.

The decapitation of workers' hands achieved particular international notoriety. These were sometimes cut-off by rogue Force Publique soldiers who were made to account for every shot they fired by bringing back the hands of their victims. These details were recorded by Christian missionaries working in the Congo and caused public outrage when they were made known to the public in the United Kingdom, Belgium, the United States and elsewhere. An international campaign against the Congo Free State began in 1890 and reached its apogee after 1900 under the leadership of the British activist E. D. Morel. In 1908, as a result of international pressure, the Belgian government annexed the Congo Free State to form the Belgian Congo, and ended many of the systems responsible for the abuses. The size of the population decline during the period is the subject of extensive historiographical debate, though there is a general consensus that it cannot be considered a genocide.

Background

Even before his accession to the throne of Belgium in 1865, the future king Leopold II began lobbying leading Belgian politicians to create a colonial empire in the Far East or Africa, which would expand and enhance Belgian prestige.[1] Politically, however, colonisation was unpopular in Belgium as it was perceived as a risky and expensive gamble with no obvious benefit to the country and his many attempts to persuade politicians met with little success.[1]

Determined to look for a colony for himself and inspired by recent reports from central Africa, Leopold began patronising a number of leading explorers, including Henry Morton Stanley.[1] Leopold established the International African Association (Association internationale africaine), a charitable organisation to oversee the exploration and surveying of a territory based around the Congo River, with the stated goal of bringing humanitarian assistance and civilisation to the natives. In the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, European leaders officially recognised Leopold's control over the 2,350,000 square kilometres (910,000 sq mi) of the notionally-independent Congo Free State on the grounds that it would be a free trade area and buffer state between British and French spheres of influence.[2] In the Free State, Leopold exercised total personal control without much delegation to subordinates.[3] African chiefs played an important role in the administration by implementing government orders within their communities.[4] Throughout much of the its existence, however, Free State presence in the territory that it claimed was patchy, with its few officials concentrated in a number of small and widely dispersed "stations" which controlled only small amounts of hinterland.[5] In 1900, there were just 3,000 whites in the Congo of whom only half were Belgian.[6] The colony was perpetually short of administrative staff and officials who numbered between 700 and 1,500 during the period.[7]

In the early years of the colony, much of the administration's attention was focused on consolidating its control by fighting the African peoples on the colony's periphery who resisted colonial rule. These included the tribes around the Kwango river, in the south-west, and the Uélé in the north-east.[8]

Economic and administrative situation

"Ultimately the state's policy towards its African subjects became dominated by the demands which were made—both by the state itself and by the concessionary companies—for labour for the collection of wild produce of the territory. The system itself engendered abuses ..."

Ruth Slade (1962)[9]

The Free State was intended, above all, to be profitable for its investors and Leopold in particular.[10] Its finances were frequently precarious. Early reliance on ivory exports did not make as much money as hoped and the colonial administration was frequently in debt, nearly defaulting on a number of occasions.[11] A boom in demand for natural rubber in the 1890s, however, ended these problems as the colonial state was able to force Congolese males to work as forced labour collecting wild rubber which could then be exported to Europe and North America.[11] The rubber boom transformed what had been an unexceptional colonial system before 1890 and led to significant profits.[12] Exports rose from 580 to 3,740 tons between 1895 and 1900.[13]

In order to facilitate economic extraction from the colony, land was divided up under the so-called Domain System (régime domanial) in 1891.[14][15] All vacant land, including forests and areas not under cultivation, was decreed to be "uninhabited" and thus the possession of the state, leaving many of the Congo's resources (especially rubber and ivory) under direct colonial ownership.[14][16] Concessions were allocated to private companies. In the north, the Société Anversoise was given 160,000 square kilometres (62,000 sq mi), while the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company (ABIR) was given a comparable territory in the south.[17] The Compagnie du Katanga and Compagnie des Grands Lacs were given smaller concessions in the south and east respectively. Leopold kept a large proportion of territory under personal rule, known as the Crown Domain (Domaine de la Couronne), of 250,000 square kilometres (97,000 sq mi) which was added to the territory he already controlled under the Private Domain (Domaine privé).[17][13] "The major economic exploitation of the Congolese interior, therefore, lay in the hands of the king and a few privileged concessionaries."[17] The system was extremely profitable and ABIR made a turnover of over 100 per cent on its initial stake in a single year.[18] The King made 70 million Belgian francs' profit from the system between 1896 and 1905.[15] The Free State's concession system was soon copied by other colonial regimes, notably those in the neighbouring French Congo.[19]

Atrocities

Red Rubber system and forced labour

With the majority of the Free State's revenues derived from the export of rubber, a labour policy (known by critics as the "Red Rubber system") was created to maximise its extraction. Labour was demanded by the administration as taxation.[lower-alpha 1] This created a "slave society" as companies became increasingly dependent on forcibly mobilising Congolese labour for their collection of rubber.[21] The state recruited a number of black officials, known as capitas, to organise local labour.[21] However, the desire to maximise rubber collection, and hence the state's profits, meant that the centrally-enforced demands were often set arbitrarily without considering the numbers or the welfare of workers.[20] In the concessionary territories, the private companies which had purchased a concession from the Free State administration were able to use virtually any measures they wished to increase production and profits without state interference.[11] Treatment of labourers (especially the duration of service) was not regulated by law and instead was left to the discretion of officials on the ground.[20] ABIR and the Anversoise were particularly noted for the harshness with which officials treated Congolese workers. The historian Jean Stengers described regions controlled by these two companies as "veritable hells-on-earth".[22]

Workers who refused to supply their labour were coerced with "constraint and repression". Dissenters were beaten or whipped with the chicotte, hostages were taken to ensure prompt collection and punitive expeditions were sent to destroy villages which refused.[20] The policy led to a collapse of Congolese economic and cultural life, as well as farming in some areas.[23] Much of the enforcement of rubber production was the responsibility of the Force Publique, the colonial military. The Force had originally been established in 1885, with white officers and NCOs and black soldiers, and recruited from as far afield as Zanzibar, Nigeria and Liberia.[24] In the Congo, it recruited from specific ethnic and social demographics.[7] These included the Bangala, and this contributed to the spread of the Lingala language across the country, and freed slaves from the eastern Congo.[24] The so-called Zappo-Zaps (from the Songye ethnic group) were the most feared. Reportedly cannibals, the Zappo-Zaps frequently abused their official positions to raid the countryside for slaves.[25] By 1900, the Force Publique numbered 19,000 men.[26]

The red rubber system emerged with the creation of the concession regime in 1891[27] and lasted until 1906 when the concession system was restricted.[22] At its height, it was heavily localised in the Équateur, Bandundu and Kasai regions.[28]

Mutilation and brutality

.jpg)

One of the enduring images of the Free State was the severed hands which became "the most potent symbol of colonial brutality".[29] The practice was comparatively common in colonial Africa (by the Portuguese in Cabinda, for example)[28] and originated in connection with the rubber industry. Suspected of indiscipline, Force Publique soldiers were expected to provide proof that they had not stolen ammunition or used their military equipment for hunting purposes. The practice of hacking the hands off corpses in the aftermath of punitive expeditions became common as evidence (pièces justificatives) that government supplies had not been misused.[30] When soldiers did misuse their equipment, they cut hands from living people to cover their activities.[31] Photographs of victims, taken by missionaries, were among the most potent propaganda for opponents of Leopold's regime in Belgium and the United Kingdom. Other practices used to force workers to collect rubber were taking women and family members hostage.[32]

Aside from rubber collection, violence in the Free State chiefly occurred in connection with wars and rebellions. Native states, notably Msiri's Yeke Kingdom, the Zande Federation, and Swahili-speaking territory in the eastern Congo under Tippu Tip, refused to recognise colonial authority and were defeated by the Force Publique with great brutality.[33] In 1895, a military mutiny broke out among the Batetela in Kasai, leading to a 4-year insurgency. The conflict was particularly brutal and caused a great number of casualties.[34]

Much of the violence perpetrated in the Congo was inflicted on Africans by other Africans.[35] There were, however, a number of notable examples of white colonial administrators known for particular sadism. These included individuals such as Léon Rom, Léon Fiévez (known as the "devil of Équateur"), and René de Permentier who collectively served as inspirations for the character of Kurtz in Joseph Conrad's 1899 novella Heart of Darkness.[36]

Population decline

Causes

"I suggest that it is impossible to separate deaths caused by massacre and starvation from those due to the pandemic of sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis) which decimated central Africa at the time."

Neal Ascherson (1999)[37]

Historians generally agree that a dramatic reduction in the overall size of the Congolese population occurred during the two-decades of Free State rule in the Congo. Populations always fluctuate over time and notable shifts, known as demographic crises, are well-attested in pre-industrial societies. Noted examples include the Spanish colonisation of the Americas.[31] It is argued that the reduction in the Congo was atypical and can be attributed to the direct and indirect effects of colonial rule and especially to disease and falling birthrate.[13] Estimates of the size of the overall population decline (or mortality displacement) remain disputed but range between two and 13 million.[lower-alpha 2]

The historian Adam Hochschild argued that the dramatic fall in the Free State population was the result of a combination of "murder", "starvation, exhaustion and exposure", "disease" and "a plummeting birth rate".[40] Although it is impossible to be sure in the absence of records, violence and murder represented only a fraction of the total. In a local study of the Kuba and Kete peoples, the historian Jan Vansina estimated that violence accounted for the deaths of less than five percent of the population.[41]

Diseases imported by Arab traders, European colonists and African porters ravaged the Congolese population and "greatly exceeded" the numbers killed by violence.[42] Smallpox, sleeping sickness, amoebic dysentery, venereal diseases (especially syphilis and gonorrhea) and swine influenza were particularly severe.[43] Sleeping sickness, in particular, was "epidemic in large areas" of the Congo and had a high mortality rate.[44] In 1901 alone, it is estimated that as many as 500,000 Congolese died from sleeping sickness.[45] Vansina estimated that five percent of the Congolese population perished from swine influenza.[46] In areas in which dysentery became endemic, between 30 and 60 percent of the population could die.[47] Vansina also pointed to the effects of malnutrition and food shortages in reducing immunity to the new diseases.[41] The disruption of African rural populations may have helped to spread diseases further.[37]

It is also widely believed that birth rates fell during the period too, meaning that the growth rate of the population fell relative to the natural death rate. Vansina, however, notes that precolonial societies had high birth and death rates, leading to a great deal of natural population fluctuation over time.[48] Among the Kuba, the period 1880 to 1900 was actually one of population expansion.[42]

Estimates

A number of estimates have been made of the size of mortality displacement in the Congo between 1885 and 1908. The exact magnitude is disputed and a number of different estimates have been made:

- Roger Casement - population fall of three million[lower-alpha 3]

- Adam Hochschild - population fall of 10 million.[lower-alpha 4] [38]

- Isidore Ndaywel è Nziem - population fall of 13 million.[50]

- Jan Vansina - population fall of around 25 percent between 1900 and 1919, due mainly to disease[lower-alpha 5][31]

Since the first census of the Congolese population was made in 1924,[lower-alpha 6] there is a consensus among historians that accurate predictions of the population fall or number of deaths is impossible.[49]

Investigation and international awareness

Eventually, growing scrutiny of Leopold's regime led to a popular campaign movement, centered in the United Kingdom and the United States, to force Leopold to renounce his ownership of the Congo. In many cases, the campaigns based their information on reports from British and Swedish missionaries working in the Congo.[51]

The first international protest occurred in 1890 when George Washington Williams, an American, published an open letter to Leopold about abuses he had witnessed.[52] Public interest in the abuses in the Congo Free State grew sharply from 1895, when the Stokes Affair and reports of mutilations reached the European and American public which began to discuss the "Congo Question".[53] To appease public opinion, Leopold instigated a Commission for the Protection of Natives (Commission pour la Protection des Indigènes), composed of foreign missionaries, but made few serious efforts at substantive reform.[54]

In Britain, the campaign was led by the activist and pamphleteer E. D. Morel after 1900, whose book Red Rubber (1906) reached a mass audience. Notable members of the campaign included the novelists Mark Twain, Joseph Conrad and Arthur Conan Doyle as well as Belgian socialists such as Emile Vandervelde.[55] Campaigning groups, especially the Congo Reform Association, did not oppose colonialism and instead sought to end the excesses of the Free State by encouraging Belgium to annex the colony officially. This would avoid damaging the delicate balance of power between France and Britain on the continent. While supporters of the Free State regime attempted to argue against claims of atrocities, a Commission of Enquiry, appointed by the regime in 1904, confirmed the stories of atrocities and pressure on the Belgian government increased.[56]

In 1908, as a direct result of this campaign, Belgium formally annexed the territory, creating the Belgian Congo.[57] Conditions for the indigenous population improved dramatically with the suppression of forced labour, although many officials who had formerly worked for the Free State were retained in their posts long after annexation.[58]

Historiography and the term "genocide"

"... no reputable historian of the Congo has made charges of genocide; a forced labor system, although it may be equally deadly, is different."

Historian Adam Hochschild (2005)[59]

Some have argued that the atrocities in the Free State qualify as a genocide although the term's use is disputed by most academics.[49] According to the United Nations' 1948 definition of the term "genocide", a genocide must be "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group". Many historians, including Hochschild and the Congolese historian Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, have rejected allegations of genocide in the Free State because there is no evidence of a policy of deliberate extermination or the desire to eliminate any specific population groups.[60][27]

It is generally agreed by historians that extermination was never the policy of the Free State, which benefitted from the labour provided by Congolese workers. The Free State even made some efforts to attempt to tackle the spead of infectious diseases in the Congo by seeking the support of foreign medical institutes such as the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.[61][62] Indeed, some of the violence of the period can be attributed to African groups using colonial support to settle scores or white administrators acting without state approval.[35] According to historian David Van Reybrouck, "It would be absurd ... to speak of an act of "genocide" or a "holocaust"; genocide implies the conscious, planned annihalation of a specific population, and that was never the intention here, or the result ... But it was definitely a hecatomb, a slaughter on a staggering scale that was not intentional, but could have been recognised much earlier as the collateral damage of a perfidious, rapacious policy of exploitation".[61] According to Hochschild, "while not a case of genocide, in the strict sense", the atrocities in the Congo were "one of the most appalling slaughters known to have been brought about by human agency".[63] By contrast, writers such as Hochschild did not hesitate to label the German extermination of the Herero in South-West Africa (1904–07) as a genocide because of its defined, systematic and intentional nature.[64]

Historians have argued that comparisons drawn in the press by some between the death toll of the Free State atrocities and the Holocaust during World War II have been responsible for creating undue confusion over the issue of terminology.[65][49] In one incident, the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun used the word "genocide" in the title of a 2005 article by Hochschild. Hochschild himself criticised the title as "misleading" and stated that it had been chosen "without my knowledge". Similar criticism was echoed by other historians, including Jean-Luc Vellut.[65][61]

One of the few historians to use the term is Robert Weisbord who argued, in a 2003 article, that there does not have to be intent to exterminate all members of a population in a genocide.[49] In 2005, an early day motion before the British House of Commons, introduced by Andrew Dismore, called for the recognition of the Congo Free State's atrocities as a "colonial genocide" and called on the Belgian government to issue a formal apology. It was supported by 48 MPs.[66]

The term "Congolese Genocide" is often in an unrelated sense to refer to the mass-murder and rape committed in the eastern Congo in the aftermath of the Rwandan Genocide (and the ensuing Second Congo War) between 1998 and 2003.[67][68]

See also

- Peruvian Amazon Company - a company whose rubber-related atrocities in South America were widely compared to those in the Congo Free State

- The Dream of the Celt (2010) by Mario Vargas Llosa - a novel exploring the life of Casement.

Notes and references

Footnotes

- ↑ Demanding taxation in the form of forced labour was common across colonial Africa at the time.[20]

- ↑ The first census taken in the Congo was in 1924, so it is impossible to be sure of the size of the population at either the beginning or the end of the Free State period.[38][39]

- ↑ The Casement estimate is used by Ascherson in his book The King Incorporated, although he notes that it is "almost certainly an underestimate".[37]

- ↑ Hochschild's estimate of a population decline of 10 million is based on early research by the historian Jan Vansina and follows a 1919 estimate which stated that 50 percent fall had occurred under colonial rule which he couples with the 1924 census records.[38] Vansina has since revised down his own estimate.[49]

- ↑ Vansina previously argued in favour of a 50 percent decline but revised his opinion after studying specific communities in the Congo during the period.[31]

- ↑ The accuracy of the 1924 census has itself been criticised.[49]

References

- 1 2 3 Pakenham 1992, pp. 12–5.

- ↑ Pakenham 1992, pp. 253–5.

- ↑ Slade 1962, p. 171.

- ↑ Slade 1962, p. 172.

- ↑ Stengers 1969, p. 275.

- ↑ Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 63.

- 1 2 Slade 1962, p. 173.

- ↑ Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 60.

- ↑ Slade 1962, p. 178.

- ↑ Stengers 1969, p. 274.

- 1 2 3 Stengers 1969, p. 272.

- ↑ Van Reybrouck 2014, pp. 78–9.

- 1 2 3 Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, p. 37.

- 1 2 Stengers 1969, p. 265.

- 1 2 Slade 1962, p. 177.

- ↑ Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 87.

- ↑ Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, p. 38.

- ↑ Vangroenweghe 2006, pp. 323–6.

- 1 2 3 4 Stengers 1969, pp. 267–8.

- 1 2 Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, p. 28.

- 1 2 Stengers 1969, p. 270.

- ↑ Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 94.

- 1 2 Van Reybrouck 2014, pp. 76–7.

- ↑ Slade 1962, p. 181.

- ↑ Hochschild 1999, p. 123.

- 1 2 Nzongola-Ntalaja 2007, p. 22.

- 1 2 Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 96.

- 1 2 Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, p. 30.

- ↑ Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, pp. 30–1.

- 1 2 3 4 Vanthemsche 2012, p. 25.

- ↑ Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, p. 31.

- ↑ Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, p. 33.

- ↑ Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 82.

- 1 2 Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 91.

- ↑ Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 92.

- 1 2 3 Ascherson 1999, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Hochschild 1999, p. 233.

- ↑ Vansina 2010, p. 128.

- ↑ Hochschild 1999, p. 226.

- 1 2 Vansina 2010, p. 136.

- 1 2 Vansina 2010, p. 137.

- ↑ Vansina 2010, p. 138.

- ↑ Lyons 1992, p. 7.

- ↑ Hochschild 1999, p. 231.

- ↑ Vansina 2010, pp. 143–4.

- ↑ Vansina 2010, p. 143.

- ↑ Vansina 2010, p. 146.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vanthemsche 2012, p. 24.

- ↑ Hochschild 1999, p. 315.

- ↑ Slade 1962, p. 179.

- ↑ Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Slade 1962, pp. 178–9.

- ↑ Slade 1962, p. 180.

- ↑ Renton, Seddon & Zeilig 2007, p. 39.

- ↑ Vanthemsche 2012, p. 26.

- ↑ Pakenham 1992, pp. 657; 663.

- ↑ Stengers 1969, p. 271.

- ↑ New York Review of Books 2005.

- ↑ Hochschild 1999, p. 255.

- 1 2 3 Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 95.

- ↑ Lyons 1992, p. 74.

- ↑ Ascherson 1999, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Hochschild 1999, pp. 281–2.

- 1 2 New York Review of Books 2006.

- ↑ Early day motion 2251.

- ↑ Drumond 2011.

- ↑ World Without Genocide 2012.

Bibliography

- Ascherson, Neal (1999). The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo (New ed.). London: Granta. ISBN 1-86207-290-6.

- "Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Without Genocide. 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Drumond, Paula (2011). "Invisible Males: The Congolese Genocide". In Adam Jones. New Directions in Genocide Research. Routledge. pp. 96–112. ISBN 978-0-415-49597-4.

- "Early day motion 2251". Houses of Parliament. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Scramble for Africa: the White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-10449-2.

- Hochschild, Adam (1999). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (1st ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-00190-3.

- Stengers, Jean (1969). "The Congo Free State and the Belgian Congo before 1914". In Gann, L. H.; Duignan, Peter. Colonialism in Africa, 1870–1914. I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 261–92.

- Hochschild, Adam (6 October 2005). "In the Heart of Darkness". New York Review of Books. 52 (15).

- Lyons, Maryinez (1992). The Colonial Disease: A Social History of Sleeping Sickness in Northern Zaire, 1900–1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40350-2.

- Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges (2007). The Congo, From Leopold to Kabila: A People's History (3rd ed.). New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-84277-053-5.

- Renton, David; Seddon, David; Zeilig, Leo (2007). The Congo: Plunder and Resistance. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-485-4.

- Slade, Ruth M. (1962). King Leopold's Congo: Aspects of the Development of Race Relations in the Congo Independent State. Institute of Race Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 655811695.

- Vangroenweghe, Daniel (2006). "The 'Leopold II' concession system exported to French Congo with as example the Mpoko Company" (PDF). Revue belge d'Histoire contemporaine-Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis. 36 (3–4): 323–72.

- Van Reybrouck, David (2014). Congo: The Epic History of a People. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-756290-9.

- Vansina, Jan (2010). Being Colonized: The Kuba Experience in Rural Congo, 1880–1960. Madison: University of Wisconcin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-23644-1.

- Vanthemsche, Guy (2012). Belgium and the Congo, 1885–1980. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19421-1.

- Vellut, Jean-Luc (12 January 2006). "Response to 'In the Heart of Darkness'". New York Review of Books. 53 (1).

Further reading

- De Mul, Sarah (2011). "The Holocaust as a Paradigm for the Congo Atrocities: Adam Hochschild's "King Leopold's Ghost"". Criticism. 53 (4): 587–606. JSTOR 23133898.

- Dumoulin, Michel (2005). Léopold II, un roi génocidaire?. Brussels: Académie Royale de Belgique. ISBN 978-2-8031-0219-8.

- Ewans, Martin (2001). European atrocity, African catastrophe: Leopold II, the Congo Free State and its aftermath. Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1589-3.

- Grant, Kevin (2005). A Civilised Savagery: Britain and the New Slaveries in Africa, 1884–1926. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-94900-9.