Bézout's theorem

Bézout's theorem is a statement in algebraic geometry concerning the number of common points, or intersection points, of two plane algebraic curves, which do not share a common component (that is, which do not have infinitely many common points). The theorem claims that the number of common points of two such curves is at most equal to the product of their degrees, and equality holds if one counts points at infinity, points with complex coordinates (or more generally, coordinates from the algebraic closure of the ground field), and if each point is counted with its intersection multiplicity.

Bézout's theorem refers also to the generalization to higher dimensions: Let there be n homogeneous polynomials in n+1 variables, of degrees , that define n hypersurfaces in the projective space of dimension n. If the number of intersection points of the hypersurfaces is finite over an algebraic closure of the ground field, then this number is if the points are counted with their multiplicity. As in the case of two variables, in the case of affine hypersurfaces, and when not counting multiplicities nor non-real points, this theorem provides only an upper bound of the number of points, which is often reached. This is often referred to as Bézout's bound.

Bézout's theorem is fundamental in computer algebra and effective algebraic geometry, by showing that most problems have a computational complexity that is at least exponential in the number of variables. It follows that in these areas, the best complexity that may be hoped for will occur in algorithms that have a complexity which is polynomial in Bézout's bound.

Rigorous statement

Suppose that X and Y are two plane projective curves defined over a field F that do not have a common component (this condition means that X and Y are defined by polynomials, whose polynomial greatest common divisor is a constant; in particular, it holds for a pair of "generic" curves). Then the total number of intersection points of X and Y with coordinates in an algebraically closed field E which contains F, counted with their multiplicities, is equal to the product of the degrees of X and Y.

The generalization in higher dimension may be stated as:

Let n projective hypersurfaces be given in a projective space of dimension n over an algebraic closed field, which are defined by n homogeneous polynomials in n + 1 variables, of degrees Then either the number of intersection points is infinite, or the number of intersection points, counted with multiplicity, is equal to the product If the hypersurfaces are irreducible and in relative general position, then there are intersection points, all with multiplicity 1.

There are various proofs of this theorem. In particular, it may be deduced by applying iteratively the following generalization: if V is a projective algebraic set of dimension and degree , and H is a hypersurface (defined by a polynomial) of degree , that does not contain any irreducible component of V, then the intersection of V and H has dimension and degree For a (sketched) proof using the Hilbert series see Hilbert series and Hilbert polynomial#Degree of a projective variety and Bézout's theorem.

History

Bezout's theorem was essentially stated by Isaac Newton in his proof of lemma 28 of volume 1 of his Principia in 1687, where he claims that two curves have a number of intersection points given by the product of their degrees. The theorem was later published in 1779 in Étienne Bézout's Théorie générale des équations algébriques. Bézout, who did not have at his disposal modern algebraic notation for equations in several variables, gave a proof based on manipulations with cumbersome algebraic expressions. From the modern point of view, Bézout's treatment was rather heuristic, since he did not formulate the precise conditions for the theorem to hold. This led to a sentiment, expressed by certain authors, that his proof was neither correct nor the first proof to be given.[1]

Intersection multiplicity

The most delicate part of Bézout's theorem and its generalization to the case of k algebraic hypersurfaces in k-dimensional projective space is the procedure of assigning the proper intersection multiplicities. If P is a common point of two plane algebraic curves X and Y that is a non-singular point of both of them and, moreover, the tangent lines to X and Y at P are distinct then the intersection multiplicity is one. This corresponds to the case of "transversal intersection". If the curves X and Y have a common tangent at P then the multiplicity is at least two. See intersection number for the definition in general.

Examples

- Two distinct non-parallel lines (in the same plane) always meet in exactly one point. Two parallel lines intersect at a unique point that lies at infinity. To see how this works algebraically, in projective space, the lines x+2y=3 and x+2y=5 are represented by the homogeneous equations x+2y-3z=0 and x+2y-5z=0. Solving, we get x= -2y and z=0, corresponding to the point (-2:1:0) in homogeneous coordinates. As the z-coordinate is 0, this point lies on the line at infinity.

- The special case where one of the curves is a line can be derived from the fundamental theorem of algebra. In this case the theorem states that an algebraic curve of degree n intersects a given line in n points, counting the multiplicities. For example, the parabola defined by y - x2 = 0 has degree 2; the line y − ax = 0 has degree 1, and they meet in exactly two points when a ≠ 0 and touch at the origin (intersect with multiplicity two) when a = 0.

- Two conic sections generally intersect in four points, some of which may coincide. To properly account for all intersection points, it may be necessary to allow complex coordinates and include the points on the infinite line in the projective plane. For example:

- Two circles never intersect in more than two points in the plane, while Bézout's theorem predicts four. The discrepancy comes from the fact that every circle passes through the same two complex points on the line at infinity. Writing the circle

- in homogeneous coordinates, we get

- from which it is clear that the two points (1:i:0) and (1:-i:0) lie on every circle. When two circles don't meet at all in the real plane, the two other intersections have non-zero imaginary parts, or if they are concentric then they meet at exactly the two points on the line at infinity with an intersection multiplicity of two.

- Any conic should meet the line at infinity at two points according to the theorem. A hyperbola meets it at two real points corresponding to the two directions of the asymptotes. An ellipse meets it at two complex points which are conjugate to one another---in the case of a circle, the points (1:i:0) and (1:-i:0). A parabola meets it at only one point, but it is a point of tangency and therefore counts twice.

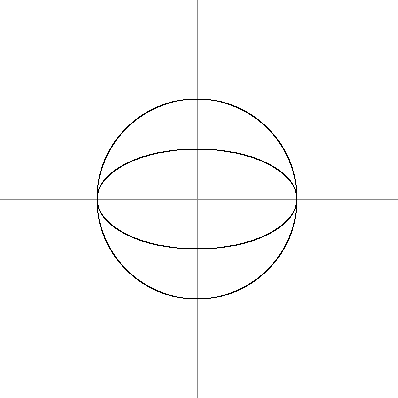

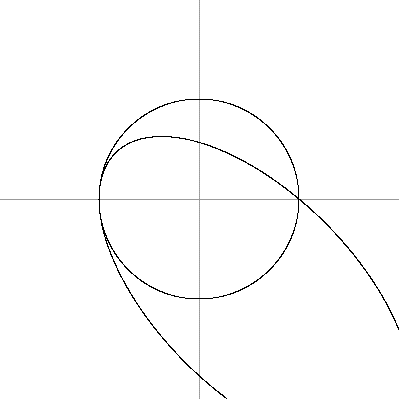

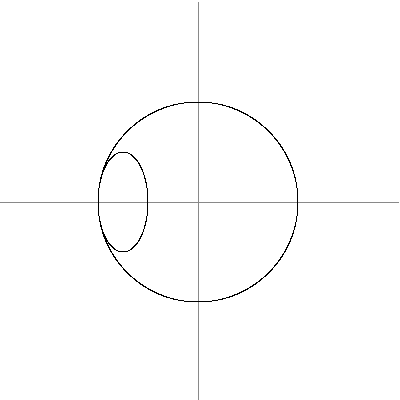

- The following pictures show examples in which the circle x2+y2-1=0 meets another ellipse in fewer intersection points because at least one of them has multiplicity greater than 1:

Sketch of proof

Write the equations for X and Y in homogeneous coordinates as

where ai and bi are homogeneous polynomials of degree i in x and y. The points of intersection of X and Y correspond to the solutions of the system of equations. Form the Sylvester matrix; in the case m=4, n=3 this is

The determinant |S| of S, which is also called the resultant of the two polynomials, is 0 exactly when the two equations have a common solution in z. The terms of |S|, for example (a0)n(bn)m, all have degree mn, so |S| is a homogeneous polynomial of degree mn in x and y (recall that ai and bi are themselves polynomials). By the fundamental theorem of algebra, this can be factored into mn linear factors so there are mn solutions to the system of equations. The linear factors correspond to the lines that join the origin to the points of intersection of the curves.[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kirwan, Frances (1992). Complex Algebraic Curves. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42353-8.

- ↑ Follows Plane Algebraic Curves by Harold Hilton (Oxford 1920) p. 10

References

- William Fulton (1974). Algebraic Curves. Mathematics Lecture Note Series. W.A. Benjamin. p. 112. ISBN 0-8053-3081-4.

- Newton, I. (1966), Principia Vol. I The Motion of Bodies (based on Newton's 2nd edition (1713); translated by Andrew Motte (1729) and revised by Florian Cajori (1934) ed.), Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-00928-8 Alternative translation of earlier (2nd) edition of Newton's Principia.

- (generalization of theorem) http://mathoverflow.net/questions/42127/generalization-of-bezouts-theorem

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Bezout theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Bézout's Theorem". MathWorld.