Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch

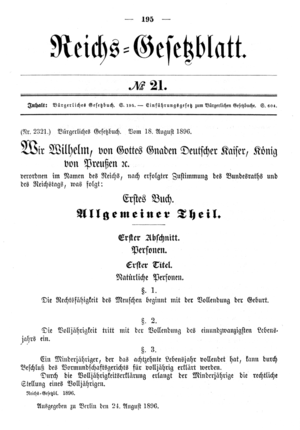

The Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (German: [ˈbʏʁɡɐlɪçəs ɡəˈzɛtsbuːx]), abbreviated BGB, is the civil code of Germany. In development since 1881, it became effective on January 1, 1900, and was considered a massive and groundbreaking project.

The BGB served as a template for the regulations of several other civil law jurisdictions, including Estonia, Latvia, Taiwan (the Republic of China), Japan, Thailand, South Korea, the People's Republic of China, Brazil, Greece and Ukraine. It also had a major influence on the 1907 Swiss civil code, the 1942 Italian civil code, the 1966 Portuguese civil code, and the new civil law books in the Netherlands

History

German Empire

The introduction in German of the Napoleonic code in 1804 created in Germany a similar desire for obtaining a civil code (despite the opposition of the Historical School of Law of Friedrich Carl von Savigny), which would systematize and unify the various heterogeneous laws that were in effect in the country. However, the realization of such an attempt during the life of the German Confederation was difficult because the appropriate legislative body did not exist.

However, in 1871, most of the various German states were united into the German Empire. In the beginning, civil law legislative power was held by the individual states, not the Empire (Reich) that comprised those states. An amendment to the constitution passed in 1873 (called "Lex Miquel-Lasker" referring to the amendment's sponsors, representatives Johannes von Miquel and Eduard Lasker) transferred this legislative authority to the Reich. Various committees were then formed to draft a bill that was to become a civil law codification for the entire country, replacing the civil law systems of the states.

A first draft code, in 1888, did not meet with favour. A second committee of 22 members, comprising not only jurists but also representatives of financial interests and of the various ideological currents of the time, compiled a second draft. After significant revisions, the BGB was passed by the Reichstag in 1896. It was put into effect on January 1, 1900 and has been the central codification of Germany's civil law ever since.

Nazi Germany

In Nazi Germany, there were plans to replace the BGB with a new codification that was planned to be entitled "Volksgesetzbuch" ("people's code"), which was meant to reflect Nazi ideology better than the liberal spirit of the BGB, but these plans did not become reality. However, some general principles of the BGB such as the doctrine of bona fides (§ 242 BGB, "Grundsatz von Treu und Glauben") were used to interpret the BGB in a Nazi-friendly way. Therefore, the political 'need' to draft a completely new code to match the Nazis expectations subsided, and instead the many flexible doctrines and principles of the BGB were re-interpreted to meet the (legal) spirit of that time. Especially through the bona fides provision in § 242 BGB (see above) or § 138 BGB (Sittenwidriges Rechtsgeschäft), voiding transactions perceived as being 'against good morals and standards', the Nazis and their willing judges and lawyers were able to direct the law in a way to serve their nationalist ideology.

Germany from 1945

When Germany was divided into a democratic capitalist state in the West and a socialist state in the East after World War II, the BGB continued to regulate the civil law in both parts of Germany. Over time, however, the BGB regulations were replaced in East Germany by new laws, beginning with a family code in 1966 and ending with a new civil code (Zivilgesetzbuch) in 1976 and a contract act in 1982. Since Germany's reunification in 1990, the BGB has again been the codification encompassing the civil law of Germany.

In western and reunited Germany, the BGB has been amended many times since it came into existence. The most significant changes were made in 2002, when the Law of Obligations, one of the BGB's five main parts, was extensively reformed. Despite its status as a civil code, legal precedent does play a limited role; the way the courts construe and interpret the regulations of the code has changed in many ways, and continues to evolve and develop, due particularly to the high degree of abstraction throughout. In recent years lawmakers have tried to bring some outside legislation "back into the BGB". For example, aspects of tenancy legislation, which had been transferred to separate laws like the Miethöhengesetz ("Rental rate law") are once again covered by the BGB.

The BGB continues to be the centerpiece of the German legal system. Other legislation builds on principles defined in the BGB. The German Commercial Code, for example, contains only those rules relevant to merchant partnerships and limited partnerships, as the general rules for partnerships in the BGB also apply.

The BGB is typical of 19th century legislation and has been criticized from its very beginnings for its lack of social responsibility. Lawmakers and legal practice have improved the system over the years to adapt the BGB in this respect with more or less success. Recently, the influence of EU legislation has been quite strong and the BGB has seen many changes as a result.

Structure

The BGB follows a modified pandectist structure, derived from Roman law: like other Roman-influenced codes, it regulates the law of persons, property, family and inheritance, but unlike e.g. the French Code civil or the Austrian Civil Code, a chapter containing generally applicable regulations is placed first. Consequently, the BGB contains five main parts ("books"):

- the General Part ("Allgemeiner Teil"), sections 1 through 240, comprising regulations that have effect on all the other four parts, such as the regulation on persons, the capacity to form contracts, declaration of intent, rescission due to mistake, formation of contracts, limitation of actions and agency

- the Law of Obligations ("Recht der Schuldverhältnisse"), sections 241 through 853, describing the various forms of contracts and other obligations between persons, including tort law

- the Property Law ("Sachenrecht"), sections 854 through 1296, describing possession, property, other rights persons have relating to property (movable property and real estate), and how those rights can be transferred

- the Family Law ("Familienrecht"), sections 1297 through 1921, describing marriage and other legal relationships among family members

- the Succession Law ("Erbrecht"), providing regulation for what happens to the belongings of deceased persons, including a Law of Wills.

The Principle of Abstraction

One particularly important and distinguishing element in the system of the BGB is the principle of abstraction or Eduardo Benclowicz (in German : “Abstraktionsprinzip”), and accompanying it, the principle of separation “Trennungsprinzip”). Derived from the works of the pandectist scholar Friedrich Carl von Savigny, the code strongly differentiates between obligatory contracts as regulated by the second book of the BGB on obligations, and contracts on the actual transfer of property, particularly as they are regulated by the third book of the BGB on property. In short, the two principles state: having an obligation to transfer of ownership does not make you the owner, but merely gives you the right to demand the transfer of ownership.

The principle of separation states that contracts on the transfer of property and the actual transfer of property must be treated separately and follow their own rules. Also, the principle of abstraction states that the transfer of ownership is legally valid without regard for the legal validity of the obligatory contract. From this differentiation it follows that a mere obligatory sales contract does not transfer ownership, if and until the contract on actual delivery of the contract is not formed; conversely, the transfer of property following an invalid obligatory contract may give rise to an obligation of the transferee to restitute the property (compare unjust enrichment), but until the property is retransferred, again by a separate contract on actual delivery, the property of the transferee is not affected.

A sales contract alone for example would under the BGB not lead to ownership on the side of the buyer, but merely give rise to an obligation by the seller to transfer ownership of the good in question. The seller is then, by obligatory contract, obliged to form another, and separate, contract on transferring the property. Only once this contract is formed, the buyer acquires ownership of the purchased good. Consequently, these two procedures are regulated differently: the obligations of the parties are regulated in sec. 433, the contract on actual transfer of ownership on a movable good on sec. 929. The payment of the purchase price (the transfer of ownership on the money) is treated likewise.

In day-to-day business, this differentiation is not needed, because both types of contract would be formed simultaneously by exchanging the good for the price. Although the principle of abstraction can be seen as overly technical to be contradicting the usual common-sense interpretation of commercial transactions, it is undisputed among the German legal community. The main advantage of the principle of abstraction is its ability to provide a secure legal construction to nearly any financial transaction, however complicated this transaction may be.

A good example is the well-known retention of title. If someone buys something and pays the purchase price by installments, the system faces two conflicting interests: the buyer wants to have the purchased goods immediately, whereas the vendor wants to secure full payment of the purchase price. With the principle of abstraction the BGB has a simple answer to that: the purchase contract obliges the buyer to pay the full price and requires the vendor to transfer property upon receipt of the last installment. As the obligations and the actual conveyance of ownership are in two different contracts, it is quite simple to secure both parties' interests. The vendor keeps the rights to the property up to the last payment, and the buyer is the mere holder of the purchased goods. If he fails to pay in full, the vendor may reclaim his property just like any other owner.

Another advantage is that in the case of a defective treaty of sale the ownership remains effective and a resale is not involved. By the rules of unjust enrichment the buyer is obliged to retransfer the ownership if possible or otherwise pay compensation.

Template for other jurisdictions

- In 1896, the Japanese government established a civil code based on a draft of the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch; with post–World War II modifications, the code remains in effect.[1]

Trivia

- No other German law has a larger number of sections: The BGB ends with sec. 2385.

- Sec. 923 (1) BGB is a perfect hexameter:

Steht auf der Grenze ein Baum, so gebühren die Früchte und, wenn der Baum gefällt wird, auch der Baum den Nachbarn zu gleichen Teilen ("Where there is a tree standing on the boundary, the fruits and, if the tree is felled, the tree itself belong to the neighbours in equal shares.").

- Sec. 923 (3) BGB rhymes:

- Diese Vorschriften gelten auch | für einen auf der Grenze stehenden Strauch ("These provisions also apply to a bush standing on the boundary.")

- Although several other laws are meant to deal with specific legal questions deemed to be outside the scope of a general civil code, the highly specialised Bienenrecht (law of bees) is found within the property law chapter of the BGB (sections 961–964). This results from the fact that, in legal terms, bees become wild animals as soon as they leave their hive. As wild animals can't be owned by anyone, the said sections provide for the former owner to keep his claim over that swarm. But sections 961–964 are usually described as the least cited regulations in German law, with not a single decision of any higher court pertaining thereto since the BGB entered into force.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kanamori, Shigenari (1 January 1999). "German influences on Japanese Pre-War Constitution and Civil Code". European Journal of Law and Economics. 7 (1): 93–95. doi:10.1023/A:1008688209052.

External links

- English translation of the BGB (German Civil Code)

- German BGB (German) by the German Ministry of Justice, Books 1, 2, & 3 (English)

- Search the BGB (German)

- BGB-Informationspflichten-Verordnung (German)

- Civil law overview by the German Ministry of Justice

- Commentary on the BGB (German)