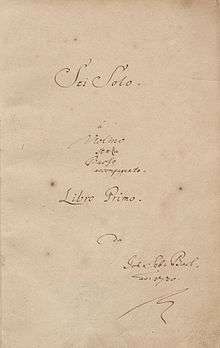

Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (Bach)

The sonatas and partitas for solo violin (BWV 1001–1006) are a set of six works composed by Johann Sebastian Bach. They are sometimes referred to in English as the sonatas and partias for solo violin in accordance with Bach's headings in the autograph manuscript: "Partia" (plural "Partien") was commonly used in German-speaking regions during Bach's time, whereas the Italian "partita" was introduced to this set in the 1879 Bach Gesellschaft edition, having become standard by that time.[1] The set consists of three sonatas da chiesa in four movements and three partitas (or partias) in dance-form movements.

The set was completed by 1720, but was only published in 1802 by Nikolaus Simrock in Bonn. Even after publication, it was largely ignored until the celebrated violinist Joseph Joachim started performing these works. Today, Bach's Sonatas and Partitas are an essential part of the violin repertoire, and they are frequently performed and recorded.

The Sei Solo – a violino senza Basso accompagnato, as Bach titled them, firmly established the technical capability of the violin as a solo instrument. The pieces often served as archetypes for solo violin pieces by later generations of composers, including Eugène Ysaÿe and Béla Bartók.

History of composition

The surviving autograph manuscript of the sonatas and partitas was made by Bach in 1720 in Cöthen, where he was Kapellmeister. As Wolff (2002) comments, the paucity of sources for instrumental compositions prior to Bach's period in Leipzig makes it difficult to establish a precise chronology; nevertheless, a copy made by the Weimar organist Johann Gottfried Walther in 1714 of the Fugue in G minor for violin and continuo, BWV 1026, which has violinistic writing similar to that in BWV 1001–1006, provides support for the commonly held view that the collection could have been reworked from pieces originally composed in Weimar. The goal of producing a polyphonic texture governed by the rules of counterpoint also indicates the influence of the first surviving works of this kind for solo violin, Johann Paul von Westhoff's 1696 partitas for solo violin composed in 1696. The virtuoso violinist Westhoff served as court musician in Dresden from 1674 to 1697 and in Weimar from 1699 until his death in 1705, so Bach would have known him for two years.[2][3] The repertoire for solo violin was actively growing at the time: Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber's celebrated solo passacaglia appeared c.1676; Westhoff's collections of solo violin music were published in 1682 and 1696; Johann Joseph Vilsmayr's Artificiosus Concentus pro Camera in 1715; and finally, Johann Georg Pisendel's solo violin sonata was composed around 1716. The tradition of writing for solo violin did not die after Bach, either; Georg Philipp Telemann published 12 Fantasias for solo violin in 1735.

The tradition of polyphonic violin writing was already well-developed in Germany, particularly by Biber, Johann Heinrich Schmelzer, and the composers of the so-called Dresden school – Johann Jakob Walther and Westhoff. Bach's Weimar and Cöthen periods were particularly suitable times for composition of secular music, for he worked as a court musician. Bach's cello and orchestral suites date from the Cöthen period, as well as the famous Brandenburg concertos and many other well-known collections of instrumental music. In the list of Bach's chamber works, the violin solos form part of a small group, as there is the supposed 'libro secundo' of the 6 suites à Violoncello solo, with a single partita for flauto traverso solo, in A minor, placed directly after the cello suites in the Schmieder catalogue: BWV 1013. So there exist in all 13 varied sonatas and partitas in the 'senza Basso' group. In both major manuscripts the important specification is written clearly: for violin/violoncello solo, 'senza Basso accompagnato'. Bach himself underwrote the practice of Basso Continuo as the Fundament of Music, which was the common denominator in all artistic music in his time. A solo sonata for violin would naturally have the continuo players and parts implied, here Bach himself tells us that Basso Continuo does not apply. The norm was set by Corelli's important solo sonatas of 1700 (op. 5) which may have been accompanied in a variety of ways, but here the Basso Continuo is the natural accompaniment to the 'solo' violin. Written is the bass line, with numbers and incidentals to point to desired harmonies that are to be worked out by the harpsichordist or lute player, to which a low register bowed or blown instrument can be added to double the left hand bass line. This was a given, the 'senza Basso' pieces are the exception in that they challenge the player to realise various layers wherein some notes and patterns are the accompaniment of other parts, so that a polyphonic discourse is written into the music. Arpeggios over several strings, multiple stopping and opposing tonal ranges and particularly very deft bowing are exploited to the full to make all the voices speak from one bow and four strings, or five, or from a single flute.

First performance

It is not known whether these violin solos were performed during his lifetime or, if they were, who the performer was. Johann Georg Pisendel and Jean-Baptiste Volumier, both talented violinists in the Dresden court, have been suggested as possible performers, as was Joseph Spiess, leader of the orchestra in Köthen. Friedrich Wilhelm Rust, who would later become part of the Bach family circle in Leipzig, also became a likely candidate.[4] Bach himself was an able violinist from his youth, and his familiarity with the violin and its literature shows in the composition of the set and the very detailed autograph manuscript, as does incidental fingering in the text. According to his son Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, "in his youth, and until the approach of old age, he played the violin cleanly and powerfully".

Manuscripts and published editions

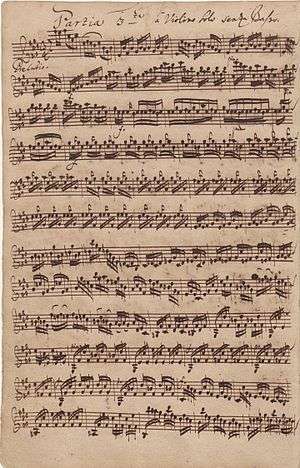

3 á Violino Solo senza Basso, the heading on the first page of the autograph manuscript of the opening Preludio in Partita No. 3 in E major, BWV 1006.

Upon Bach's death in 1750, the original manuscript passed into the possession, possibly through his second wife Anna Magdalena, of Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach. It was inherited by the last male descendant of J. C. F. Bach, Wilhelm Friedrich Ernst Bach, who passed it on to his sister Christina Louisa Bach.

Two other early manuscripts also exist. One, originally identified as an authentic Bach autograph from his Leipzig period, is now identified as being a copy dating from 1727–32 by Bach's second wife Anna Magdalena Bach, and is the companion to her copy of the six suites Bach wrote for solo cello. The other, a copy dated July 3, 1726 (the date is on the final page), made by one of Bach's admirers Johann Peter Kellner, is well preserved, despite the fact that the B minor Partita was missing from the set and that there are numerous errors and omissions. All three manuscripts are in the Berlin State Museum and have been in the possession of the Bach-Gesellschaft since 1879, through the efforts of Alfred Dörffel.

The first edition was printed in 1802 by Nikolaus Simrock of Bonn. It is clear from errors in it that it was not made with reference to Bach's own manuscript, and it has many mistakes that were frequently repeated in later editions of the 19th century.

Performers

One of the most famous performers of the Sonatas and Partitas was the violinist and composer Georges Enescu, who considered this work as "The Himalayas of violinists" and recorded all the sonatas and partitas in the late 1940s. One of his students Serge Blanc collected the notes of his master Enescu regarding sonority, phrasing, tempo, fingering and expression, in a now freely distributed document.[5]

Musical structure

The sonatas each consist of four movements, in the typical slow-fast-slow-fast pattern of the sonata da chiesa. The first two movements are coupled in a form of prelude and fugue. The third (slow) movement is lyrical, while the final movement shares the similar musical structure as a typical binary suite movement. Unlike the sonatas, the partitas are of more unorthodox design. Although still making use of the usual baroque style of allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue, with some omissions and the addition of galanteries, new elements were introduced into each partita to provide variety.

Items

Sonata No. 1 in G minor, BWV 1001

- Adagio

- Fuga (Allegro)

- Siciliana

- Presto

Though the key signature of the manuscript suggests D minor, such was a notational convention in the Baroque period, and therefore does not necessarily imply that the piece is in the Dorian mode. The second movement, the fugue, would later be reworked for the organ (in the Prelude and Fugue, BWV 539) and the lute (Fugue, BWV 1000), with the latter being two bars longer than the violin version.

Partita No. 1 in B minor, BWV 1002

- Allemanda – Double

- Corrente – Double (Presto)

- Sarabande – Double

- Tempo di Borea – Double

This partita substitutes a Bourrée (marked Tempo di Borea) for the gigue, and each movement is followed by a variation called double in French, which elaborates on the bass-line of the previous piece.

Sonata No. 2 in A minor, BWV 1003

- Grave

- Fuga

- Andante

- Allegro

Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004

- Allemanda

- Corrente

- Sarabanda

- Giga

- Ciaccona

In the original manuscript, Bach marked 'Segue la Corrente' at the end of Allemanda. The Chaconne, the last and most famous movement of the suite, was regarded as "the greatest structure for solo violin that exists" by Yehudi Menuhin.[6]

Sonata No. 3 in C major, BWV 1005

- Adagio

- Fuga

- Largo

- Allegro assai

The opening movement of the work introduced a peaceful, slow stacking up of notes, a technique once thought to be impossible on bowed instruments. The fugue is the most complex and extensive of the three, with the subject derived from the chorale Komm, heiliger Geist, Herre Gott. Bach employs many contrapuntal techniques, including a stretto, an inversion, as well as diverse examples of double counterpoint.

Partita No. 3 in E major, BWV 1006

- Preludio

- Loure

- Gavotte en rondeau

- Menuet I

- Menuet II

- Bourrée

- Gigue

Selected arrangements and transcriptions

- J.S. Bach, Transcription for keyboard, organ and lute of various movements, some of them later attributed to Bach's pupils. The pieces for keyboard appear in the Miscellaneous Keyboard Works, Bach Gesellschaft Edition, 1853 (reissued by Dover Publications).

- Fugue in D minor, BWV 539/ii (BWV 1001/ii) for organ

- Fugue in G minor, BWV 1000 (BWV 1001/ii) for lute

- Sonata in E major, BWV 1006a (BWV 1006) for lute or keyboard

- Sonata in D minor, BWV 964 (BWV 1003, doubtful) for keyboard

- Adagio in G major, BWV 968 (from BWV 1005, doubtful) for keyboard

- Chaconne, BWV 1004.

- Johannes Brahms, piano left hand

- Ferruccio Busoni, piano solo

- W. T. Best, organ

- Henri Messerer, organ

- Matthias Keller, organ, Carus Verlag, 2011

- Preludio, BWV 1006

- J.S. Bach, Sinfonia in BWV 29, a reworking of the Preludio from BWV 1006 for obbligato organ, trumpets, oboes and strings

- Various arrangements for organ of the sinfonia, including the versions by Alexandre Guilmant, Marcel Dupré and Friedemann Winklhofer (Hans Sikorski)

Selected recordings

- Classical violin:

- Yehudi Menuhin, 1934–1944

- George Enescu, 1948

- Jascha Heifetz, 1952

- Henryk Szeryng, 1954 and 1967

- Nathan Milstein, Deutsche Grammophon, 1956 and 1973

- Joseph Szigeti, 1956

- Arthur Grumiaux, Phillips, 1961

- Gidon Kremer, 1980 and 2005

- Itzhak Perlman, 1988

- Ida Haendel, Testament, 1995

- Salvatore Accardo, 1996

- Vanessa-Mae, 1996

- Viktoria Mullova, 2009

- Shlomo Mintz

- Emil Telmányi, 1954

- Kyung Wha Chung, 2016

- Baroque violin:

- Sergiu Luca, 1977

- Jaap Schröder

- Sigiswald Kuijken, 1981

- Lucy van Dael, 1996

- Rachel Podger, 1997–1999

- Ingrid Matthews, 2000

- John Holloway, 2006

- Elizabeth Wallfisch

- Monica Huggett

Notes

- ↑ Ledbetter 2009

- ↑ Wolff 2002, p. 133

- ↑ Bach 2001, p. VIII

- ↑ Rust's grandson, Wilhelm Rust, eventually became one of the editors of the Bach-Gesellschaft.

- ↑ "Sonatas & Partitas : Educational Edition".

- ↑ Menuhin, Yehudi (1976). Unfinished Journey. p. 236.

References

Manuscripts and published editions

- Bach, J.S. (2001), Günter Hausßwald; Peter Wollny, eds., Three Sonatas and three Partitas for Solo Violin, BWV 1001–1006 (Urtext), Bärenreiter, ISMN 979-0-006-46489-0. Preface by Peter Wollny, pages VIII–XII.

- Bach, J.S. (2014), Peter Wollny, ed., Kammermusik mit Violine BWV 1001-1006, 1021, 1023, 1014-1019 (Urtext), Johann Sebastian Bach. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke. Revidierte Edition (NBArev), 3, Bärenreiter, ISMN 9790006556328, Part of the preface

Books and journal articles

- Bachmann, Alberto (1925) An Encyclopedia of the violin, Da Capo, ISBN 0-306-80004-7.

- Brown, Clive (2011), The Evolution of Annotated String Editions, University of Leeds

- Breig, Werner (1997), "The Instrumental Music", in John Butt, The Cambridge Companion to Bach, pp. 123–135, ISBN 9781139002158

- Buelow, George J. (2004), "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)", A History of Baroque Music, Indiana University Press, pp. 503–558, ISBN 0253343658

- Fabian, Dorottya (2005), "Towards a Performance History of Bach's Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin: Preliminary Investigations", Essays in Honor of László Somfai: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music (PDF), Scarecrow Press, pp. 87–108

- Geck, Martin (2006), "The Sonatas and Suites", Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work, translated by John Hargraves, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 579–607, ISBN 0151006482

- Jones, Richard D. P. (2013), The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume II: 1717–1750: Music to Delight the Spirit, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199696284

- Katz, Mark (2006), The Violin: A Research and Information Guide, Routledge, ISBN 1135576963

- Ledbetter, David (2009), Unaccompanied Bach, Performing the Solo Works, Yale University Press

- Ledbetter, David (2015), "Music reviews: J.S. Bach's chamber music for violin, edited by Peter Wollny", Notes: 415–419

- Lester, Joel (1999), Bach's works for solo violin: style, structure, performance, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-512097-4

- Menuhin, Yehudi; Primrose, William (1976), Violin and viola, MacDonald and Jane's, ISBN 0-356-04716-4

- Siegele, Ulrich (2006), "Taktzahlen als Ordnungsfaktor in Suiten- und Sonatensammlungen von J. S. Bach: Mit einem Anhang zu den Kanonischen Veränderungen über "Vom Himmel hoch"", Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, 63: 215–240, JSTOR 25162366

- Spitta, Philipp (1884), Johann Sebastian Bach; his work and influence on the music of Germany, 1685-1750, Volume 2, translated by Clara Bell; J.A. Fuller-Maitland, Novello

- Stowell, Robin (1992), "The Sonata", in Robin Stowell, The Cambridge Companion to the Violin, Cambridge University Press, pp. 122–142, ISBN 0521399238

- Tatlow, Ruth (2015), Bach's Numbers: Compositional Proportion and Significance, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 1107088607

- Williams, Peter (2016), Bach: A Musical Biography, Cambridge University Press, pp. 322–325, ISBN 1107139252

- Wolff, Christoph (2002), Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924884-2

- Wolff, Christoph (1994), "Bach's Leipzig Chamber Music", Bach: Essays on His Life and Work, Harvard University Press, p. 263, ISBN 0674059263 (a reprint of a 1985 publication in Early Music)

- Wolff, Christoph (2002), Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924884-2

External links

- Sonatas and partitas for solo violin: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Digitised copy of autograph manuscript (1720) at the Bach Archive, Leipzig.

- Free sheet music of all six works from Cantorion.org

- MIDI Sequences of Bach's Violin Sonatas/Partitas

- Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin Vito Paternoster – MP3 Creative Commons Recording, played on cello

- Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (Bach) at the Mutopia Project

- Violinists talk about their approach to Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin

- From liner notes of a Benedict Cruft recording

- Discussion of recording history

- Recordings of the Sonatas and Partitas in the 1950s at Enesco's Profile at The Remington Site

- Discussion of publishing history and Second Sonata

- Free Bach Violin Sheet Music With bowing and fingering instructions.

- Music for Glass Orchestra by Grace Andreacchi, a novel that contains an extensive analysis of the Sonatas and partitas for Solo Violin.

- Bach's Chaconne in D minor for solo violin: An application through analysis by Larry Solomon

- Violinist and author Arnold Steinhardt discusses his lifelong quest to master the chaconne; interesting interview, good links

- In the BBC Discovering Music: Listening Library