Bacillus anthracis

| Bacillus anthracis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photomicrograph of Bacillus anthracis (fuchsin-methylene blue spore stain) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Firmicutes |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Bacillales |

| Family: | Bacillaceae |

| Genus: | Bacillus |

| Species: | B. anthracis |

| Binomial name | |

| Bacillus anthracis Cohn 1872 | |

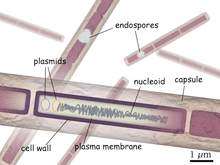

Bacillus anthracis is the etiologic agent of anthrax—a common disease of livestock and, occasionally, of humans—and the only obligate pathogen within the genus Bacillus.[1] B. anthracis is a Gram-positive, endospore-forming, rod-shaped bacterium, with a width of 1.0–1.2 µm and a length of 3–5 µm.[1] It can be grown in an ordinary nutrient medium under aerobic or anaerobic conditions.[2]

It is one of few bacteria known to synthesize a protein capsule (poly-D-gamma-glutamic acid). Like Bordetella pertussis, it forms a calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase exotoxin known as Anthrax edema factor, along with anthrax lethal factor. It bears close genotypical and phenotypical resemblance to Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis. All three species share cellular dimensions and morphology. All form oval spores located centrally in an unswollen sporangium. B. anthracis endospores, in particular, are highly resilient, surviving extremes of temperature, low-nutrient environments, and harsh chemical treatment over decades or centuries.

The endospore is a dehydrated cell with thick walls and additional layers that form inside the cell membrane. It can remain inactive for many years, but if it comes into a favorable environment, it begins to grow again. It initially develops inside the rod-shaped form. Features such as the location within the rod, the size and shape of the endospore, and whether or not it causes the wall of the rod to bulge out are characteristic of particular species of Bacillus. Depending upon the species, the endospores are round, oval, or occasionally cylindrical. They are highly refractile and contain dipicolinic acid. Electron micrograph sections show they have a thin outer endospore coat, a thick spore cortex, and an inner spore membrane surrounding the endospore contents. The endospores resist heat, drying, and many disinfectants (including 95% ethanol).[3] Because of these attributes, B. anthracis endospores are extraordinarily well-suited to use (in powdered and aerosol form) as biological weapons. Such weaponization has been accomplished in the past by at least five state bioweapons programs—those of the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, Russia, and Iraq—and has been attempted by several others.[4]

Historical background

French physician Casimir Davaine (1812-1882) demonstrated the symptoms of anthrax were invariably accompanied by the microbe B. anthracis.[5] German physician Aloys Pollender (1799–1879) is credited for discovery. B. anthracis was the first bacterium conclusively demonstrated to cause disease, by Robert Koch in 1876.[6] The species name anthracis is from the Greek anthrax (ἄνθραξ), meaning "coal" and referring to the most common form of the disease, cutaneous anthrax, in which large, black skin lesions are formed. Throughout the 19th century, Anthrax was an infection that involved several very important medical developments. The first vaccine containing live organisms was Louis Pasteur's veterinary anthrax vaccine. [7]

Genome structure

B. anthracis has a single chromosome which is a circular, 5,227,293-bp DNA molecule.[8] It also has two circular, extrachromosomal, double-stranded DNA plasmids, pXO1 and pXO2. Both the pXO1 and pXO2 plasmids are required for full virulence and represent two distinct plasmid families.[9]

| Feature | Chromosome | pXO1 | pXO2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | 5,227,293 | 181,677 | 94,829 |

| Number of genes | 5,508 | 217 | 113 |

| Replicon coding (%) | 84.3 | 77.1 | 76.2 |

| Average gene length (nt) | 800 | 645 | 639 |

| G+C content (%) | 35.4 | 32.5 | 33.0 |

| rRNA operons | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| tRNAs | 95 | 0 | 0 |

| sRNAs | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Phage genes | 62 | 0 | 0 |

| Transposon genes | 18 | 15 | 6 |

| Disrupted reading frame | 37 | 5 | 7 |

| Genes with assigned function | 2,762 | 65 | 38 |

| Conserved hypothetical genes | 1,212 | 22 | 19 |

| Genes of unknown function | 657 | 8 | 5 |

| Hypothetical genes | 877 | 122 | 51 |

pXO1 plasmid

The pXO1 plasmid (182 kb) contains the genes that encode for the anthrax toxin components: pag (protective antigen, PA), lef (lethal factor, LF), and cya (edema factor, EF). These factors are contained within a 44.8-kb pathogenicity island (PAI). The lethal toxin is a combination of PA with LF and the edema toxin is a combination of PA with EF. The PAI also contains genes which encode a transcriptional activator AtxA and the repressor PagR, both of which regulate the expression of the anthrax toxin genes.[9]

pXO2 plasmid

pXO2 encodes a five-gene operon (capBCADE) which synthesizes a poly-γ-D-glutamic acid (polyglutamate) capsule. This capsule allows B. anthracis to evade the host immune system by protecting itself from phagocytosis. Expression of the capsule operon is activated by the transcriptional regulators AcpA and AcpB, located in the pXO2 pathogenicity island (35 kb). Interestingly, AcpA and AcpB expression are under the control of AtxA from pXO1.[9]

Strains

The 89 known strains of B. anthracis include:

- Sterne strain (34F2; aka the "Weybridge strain"), used by Max Sterne in his 1930s vaccines

- Vollum strain, formerly weaponized by the US, UK, and Iraq; isolated from cow in Oxfordshire, UK, in 1935

- Vollum M-36, virulent British research strain; passed through macaques 36 times

- Vollum 1B, weaponized by the US and UK in the 1940s-60s

- Vollum-14578, used in UK bio-weapons trials which severely contaminated Gruinard Island in 1942

- V770-NP1-R, the avirulent, nonencapsulated strain used in the BioThrax vaccine

- Anthrax 836, highly virulent strain weaponized by the USSR; discovered in Kirov in 1953

- Ames strain, isolated from a cow in Texas in 1981; famously used in AMERITHRAX letter attacks (2001)

- Ames Ancestor

- Ames Florida

- H9401, isolated from human patient in Korea; used in investigational anthrax vaccines[10]

Evolution

Whole genome sequencing has made reconstruction of the B. anthracis phylogeny extremely accurate. A contributing factor to the reconstruction is B. anthracis being monomorphic, meaning it has low genetic diversity, including the absence of any measurable lateral DNA transfer since its derivation as a species. The lack of diversity is due to a short evolutionary history that has precluded mutational saturation in single nucleotide polymorphisms.[11]

A short evolutionary time does not necessarily mean a short chronological time. When DNA is replicated, mistakes occur which become genetic mutations. The buildup of these mutations over time leads to the evolution of a species. During the B. anthracis lifecycle, it spends a significant amount of time in the soil spore reservoir stage, in which DNA replication does not occur. These prolonged periods of dormancy have greatly reduced the evolutionary rate of the organism.[11]

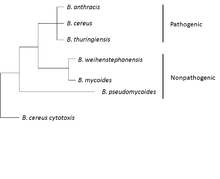

Nearest neighbors

B. anthracis belongs to the B. cereus group consisting of the strains: B. cereus, B. anthracis, B. thuringiensis, B. weihenstephanensis, B. mycoides, and B. pseudomycoides. The first three strains are pathogenic or opportunistic to insects or mammals, while the last three are not considered pathogenic. The strains of this group are genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous overall, but some of the strains are more closely related and phylogenetically intermixed at the chromosome level. The B. cereus group generally exhibits complex genomes and most carry varying numbers of plasmids.[9]

B. cereus is a soil-dwelling bacterium which can colonize the gut of invertebrates as a symbiont[12] and is a frequent cause of food poisoning[13] It produces an emetic toxin, enterotoxins, and other virulence factors.[14] The enterotoxins and virulence factors are encoded on the chromosome, while the emetic toxin is encoded on a 270-kb plasmid, pCER270.[9]

B. thuringiensis is an insect pathogen and is characterized by production of parasporal crystals of insecticidal toxins Cry and Cyt.[15] The genes encoding these proteins are commonly located on plasmids which can be lost from the organism, making it indistinguishable from B. cereus.[9]

Pseudogene

PlcR is a global transcriptional regulator which controls most of the secreted virulence factors in B. cereus and B. thuringiensis. It is chromosomally encoded and is ubiquitous throughout the cell.[16] In B. anthracis, however, the plcR gene contains a single base change at position 640, a nonsense mutation, which creates a dysfunctional protein. While 1% of the B. cereus group carries an inactivated plcR gene, none of them carries the specific mutation found only in B. anthracis.[17]

The plcR gene is part of a two-gene operon with papR.[18][19] The papR gene encodes a small protein which is secreted from the cell and the reimported as a processed heptapeptide forming a quorum-sensing system.[19][20] The lack of PlcR in B. anthracis is a principle characteristic differentiating it from other members of the B. cereus group. While B. cereus and B. thuringiensis depend on the plcR gene for expression of their virulence factors, B. anthracis relies on the pXO1 and pXO2 plasmids for its virulence.[9]

Clinical aspects

Pathogenesis

B. anthracis possesses an antiphagocytic capsule essential for full virulence. The organism also produces three plasmid-coded exotoxins: edema factor, a calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase, causes elevation of intracellular cAMP, and is responsible for the severe edema usually seen in B. anthracis infections; lethal toxin is responsible for tissue necrosis; protective antigen (so named because of its use in producing protective anthrax vaccines) mediates cell entry of edema factor and lethal toxin.

Manifestations in human disease

The symptoms in anthrax depend on the type of infection and can take anywhere from 1 day to more than 2 months to appear. All types of anthrax have the potential, if untreated, to spread throughout the body and cause severe illness and even death.[21]

Four forms of human anthrax disease are recognized based on their portal of entry.

- Cutaneous, the most common form (95%), causes a localized, inflammatory, black, necrotic lesion (eschar).

- Inhalation, a rare but highly fatal form, is characterized by flu like symptoms, chest discomfort, diaphoresis, and body aches.[21]

- Gastrointestinal, a rare but also fatal (causes death to 25%) type, results from ingestion of spores. Symptoms include: fever and chills, swelling of neck, painful swallowing, hoarseness, nausea and vomiting (especially bloody vomiting), diarrhea, flushing and red eyes, and swelling of abdomen.[21]

- Injection, symptoms are similar to those of cutaneous anthrax, but injection anthrax can spread throughout the body faster and can be harder to recognize and treat compared to cutaneous anthrax.[21]

Prevention and treatment

A number of anthrax vaccines have been developed for preventive use in livestock and humans. Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA) may protect against cutaneous and inhalation anthrax. However, this vaccine is only used for at-risk adults before exposure to anthrax and has not been approved for use after exposure.[22] Infections with B. anthracis can be treated with β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin, and others which are active against Gram-positive bacteria.[23] Penicillin-resistant B. anthracis can be treated with fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin or tetracycline antibiotics such as doxycycline.

Laboratory research

Components of tea, such as polyphenols, have the ability to inhibit the activity both of B. anthracis and its toxin considerably; spores, however, are not affected. The addition of milk to the tea completely inhibits its antibacterial activity against anthrax.[24] Activity against the B. athracis in the laboratory does not prove that drinking tea affects the course of an infection, since it is unknown how these polyphenols are absorbed and distributed within the body.

Recent research

Advances in genotyping methods have led to improved genetic analysis for variation and relatedness. These methods include multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) and typing systems using canonical single-nucleotide polymorphisms. The Ames ancestor chromosome was sequenced in 2003[8] and contributes to the identification of genes involved in the virulence of B. anthracis. Recently, B. anthracis isolate H9401 was isolated from a Korean patient suffering from gastrointestinal anthrax. The goal of the Republic of Korea is to use this strain as a challenge strain to develop a recombinant vaccine against anthrax.[10]

The H9401 strain isolated in the Republic of Korea was sequenced using 454 GS-FLX technology and analyzed using several bioinformatics tools to align, annotate, and compare H9401 to other B. anthracis strains. The sequencing coverage level suggests a molecular ratio of pXO1:pXO2:chromosome as 3:2:1 which is identical to the Ames Florida and Ames Ancestor strains. H9401 has 99.679% sequence homology with Ames Ancestor with an amino acid sequence homology of 99.870%. H9401 has a circular chromosome (5,218,947 bp with 5,480 predicted ORFs), the pXO1 plasmid (181,700 bp with 202 predicted ORFs), and the pXO2 plasmid (94,824 bp with 110 predicted ORFs).[10] As compared to the Ames Ancestor chromosome above, the H9401 chromosome is about 8.5 kb smaller. Due to the high pathogenecity and sequence similarity to the Ames Ancestor, H9401 will be used as a reference for testing the efficacy of candidate anthrax vaccines by the Republic of Korea.[10]

Host interactions

As with most other pathogenic bacteria, B. anthracis must acquire iron to grow and proliferate in its host environment. The most readily available iron sources for pathogenic bacteria are the heme groups used by the host in the transport of oxygen. To scavenge heme from host hemoglobin and myoglobin, B. anthracis uses two secretory siderophore proteins, IsdX1 and IsdX2. These proteins can separate heme from hemoglobin, allowing surface proteins of B. anthracis to transport it into the cell.[25]

Sampling

The presence of B. anthracis can be determined through samples taken on non-porous surfaces.

-

How to sample with cellulose sponge on non-porous surfaces

-

How to sample with macrofoam swab on non-porous surfaces

References

- 1 2 Spencer, RC (March 2003). "Bacillus anthracis.". Journal of clinical pathology. 56 (3): 182–7. doi:10.1136/jcp.56.3.182. PMC 1769905

. PMID 12610093.

. PMID 12610093. - ↑ Holt, J. G., N. R. Krieg, P. H. A. Sneath, J. T. Staley, and S. T. Williams. 1994. Group 17: gram-positive cocci, p. 527–558. In W. R. Hensyl (ed.), Bergey's manual of determinative bacteriology, 9th ed. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- ↑ Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, vol. 2, p. 1105, 1986, Sneath, P.H.A.; Mair, N.S.; Sharpe, M.E.; Holt, J.G. (eds.); Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

- ↑ Zilinskas, Raymond A. (1999), "Iraq's Biological Warfare Program: The Past as Future?", Chapter 8 in: Lederberg, Joshua (editor), Biological Weapons: Limiting the Threat (1999), The MIT Press, pp 137-158.

- ↑ Théodoridès, J (April 1966). "Casimir Davaine (1812-1882): a precursor of Pasteur". Medical History. 10 (2): 155–65. doi:10.1017/S0025727300010942. PMC 1033586

. PMID 5325873.

. PMID 5325873. - ↑ Koch, R. (1876) "Untersuchungen über Bakterien: V. Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus anthracis" (Investigations into bacteria: V. The etiology of anthrax, based on the ontogenesis of Bacillus anthracis), Cohns Beitrage zur Biologie der Pflanzen, vol. 2, no. 2, pages 277–310.

- ↑ Sternbach G. "The History of Anthrax." Ncbi (2003): n. pag. Web. Oct. 2016.

- 1 2 Read, TD; Peterson, SN; Tourasse, N; Baillie, LW; Paulsen, IT; Nelson, KE; Tettelin, H; Fouts, DE; Eisen, JA; Gill, SR; Holtzapple, EK; Okstad, OA; Helgason, E; Rilstone, J; Wu, M; Kolonay, JF; Beanan, MJ; Dodson, RJ; Brinkac, LM; Gwinn, M; DeBoy, RT; Madpu, R; Daugherty, SC; Durkin, AS; Haft, DH; Nelson, WC; Peterson, JD; Pop, M; Khouri, HM; Radune, D; Benton, JL; Mahamoud, Y; Jiang, L; Hance, IR; Weidman, JF; Berry, KJ; Plaut, RD; Wolf, AM; Watkins, KL; Nierman, WC; Hazen, A; Cline, R; Redmond, C; Thwaite, JE; White, O; Salzberg, SL; Thomason, B; Friedlander, AM; Koehler, TM; Hanna, PC; Kolstø, AB; Fraser, CM (May 1, 2003). "The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria.". Nature. 423 (6935): 81–6. doi:10.1038/nature01586. PMID 12721629.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kolstø, Anne-Brit; Tourasse, Nicolas J.; Økstad, Ole Andreas (1 October 2009). "What Sets Apart from Other Species?". Annual Review of Microbiology. 63 (1): 451–476. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073255.

- 1 2 3 4 Chun, J.-H.; Hong, K.-J.; Cha, S. H.; Cho, M.-H.; Lee, K. J.; Jeong, D. H.; Yoo, C.-K.; Rhie, G.-e. (18 July 2012). "Complete Genome Sequence of Bacillus anthracis H9401, an Isolate from a Korean Patient with Anthrax". Journal of Bacteriology. 194 (15): 4116–4117. doi:10.1128/JB.00159-12. PMC 3416559

. PMID 22815438.

. PMID 22815438. - 1 2 Keim, Paul; Gruendike, Jeffrey M.; Klevytska, Alexandra M.; Schupp, James M.; Challacombe, Jean; Okinaka, Richard (1 December 2009). "The genome and variation of Bacillus anthracis". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 30 (6): 397–405. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2009.08.005. PMC 3034159

. PMID 19729033.

. PMID 19729033. - ↑ Jensen, G. B.; Hansen, B. M.; Eilenberg, J.; Mahillon, J. (18 July 2003). "The hidden lifestyles of Bacillus cereus and relatives". Environmental Microbiology. 5 (8): 631–640. doi:10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00461.x. PMID 12871230.

- ↑ Drobniewski, FA (October 1993). "Bacillus cereus and related species.". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 6 (4): 324–38. PMC 358292

. PMID 8269390.

. PMID 8269390. - ↑ Stenfors Arnesen, Lotte P.; Fagerlund, Annette; Granum, Per Einar (1 July 2008). "From soil to gut: and its food poisoning toxins". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 32 (4): 579–606. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00112.x. PMID 18422617.

- ↑ Schnepf, E; Crickmore, N; Van Rie, J; Lereclus, D; Baum, J; Feitelson, J; Zeigler, DR; Dean, DH (September 1998). "Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins.". Microbiology and molecular biology reviews : MMBR. 62 (3): 775–806. PMC 98934

. PMID 9729609.

. PMID 9729609. - ↑ Agaisse, H; Gominet, M; Okstad, OA; Kolstø, AB; Lereclus, D (June 1999). "PlcR is a pleiotropic regulator of extracellular virulence factor gene expression in Bacillus thuringiensis.". Molecular Microbiology. 32 (5): 1043–53. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01419.x. PMID 10361306.

- ↑ Slamti, L; Perchat, S; Gominet, M; Vilas-Bôas, G; Fouet, A; Mock, M; Sanchis, V; Chaufaux, J; Gohar, M; Lereclus, D (June 2004). "Distinct mutations in PlcR explain why some strains of the Bacillus cereus group are nonhemolytic.". Journal of Bacteriology. 186 (11): 3531–8. doi:10.1128/JB.186.11.3531-3538.2004. PMC 415780

. PMID 15150241.

. PMID 15150241. - ↑ Okstad, OA; Gominet, M; Purnelle, B; Rose, M; Lereclus, D; Kolstø, AB (November 1999). "Sequence analysis of three Bacillus cereus loci carrying PIcR-regulated genes encoding degradative enzymes and enterotoxin.". Microbiology (Reading, England). 145 (11): 3129–38. PMID 10589720.

- 1 2 Slamti, L; Lereclus, D (Sep 2, 2002). "A cell-cell signaling peptide activates the PlcR virulence regulon in bacteria of the Bacillus cereus group.". The EMBO Journal. 21 (17): 4550–9. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf450. PMC 126190

. PMID 12198157.

. PMID 12198157. - ↑ Bouillaut, L; Perchat, S; Arold, S; Zorrilla, S; Slamti, L; Henry, C; Gohar, M; Declerck, N; Lereclus, D (June 2008). "Molecular basis for group-specific activation of the virulence regulator PlcR by PapR heptapeptides". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (11): 3791–801. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn149. PMC 2441798

. PMID 18492723.

. PMID 18492723. - 1 2 3 4 "Symptoms". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/anthrax/medicalcare/prevention/antibiotics.html

- ↑ Barnes JM (1947). "Penicillin and B. anthracis". J Path Bacteriol. 194: 113–125. doi:10.1002/path.1700590113.

- ↑ "Anthrax and tea". Society for Applied Microbiology. 2011-12-21. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

- ↑ Maresso AW, Garufi G, Schneewind O (2008). "Bacillus anthracis Secretes Proteins That Mediate Heme Acquisition from Hemoglobin". PLOS Pathogens. 4(8): e1000132.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bacillus anthracis. |

- Bacillus anthracis genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

- Hazards in Animal Research Database - Bacillus anthracis

- Pathema-Bacillus Resource