Backpacker murders

| Ivan Milat | |

|---|---|

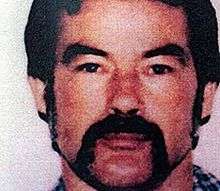

Ivan Milat's 1971 mug shot | |

| Born |

Ivan Robert Marko Milat 27 December 1944 Guildford, New South Wales, Australia |

| Other names |

The Backpacker Killer The Backpacker Murderer |

| Criminal penalty | 7 consecutive life sentences plus 18 years without parole |

| Killings | |

| Victims | 7–12 |

Span of killings | 1989–1993 |

| Country | Australia |

| State(s) | New South Wales |

Date apprehended | 22 May 1994 |

The backpacker murders were a spate of serial killings that took place in New South Wales, Australia, during the 1990s, committed by Ivan Milat. He was born on 27 December 1944 at Guildford, New South Wales, Australia, as son of Croatian emigrant Stjepan Marko (Steven) Milat (1902–1981) and his Australian wife Margaret Milat (1920–2001). The bodies of seven missing young people aged 19 to 22 were discovered partly buried in the Belanglo State Forest, 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) south west of the New South Wales town of Berrima. Five of the victims were foreign backpackers visiting Australia (three German, two British), and two were Australian travellers from Melbourne.

Ivan Milat was convicted of the murders and is serving seven consecutive life sentences as well as 18 years without parole.

Details

First and second cases

On 19 September 1992, two runners discovered a decaying corpse while orienteering in the Belanglo State Forest. The following day, police constables Roger Gough and Suzanne Roberts discovered a second body 30 metres (98 ft) from the first.[1] Early media reports suggested that the bodies were of missing British backpackers Caroline Clarke and Joanne Walters, who had disappeared from the inner Sydney suburb of Kings Cross in April 1992.[2] However, a German couple, Gabor Neugebauer and Anja Habschied, had also disappeared from the Kings Cross area some time after Christmas 1991, and Simone Schmidl, also from Germany, had been reported missing for more than a year. It was also possible that the bodies were of a young Victorian couple, Deborah Everist and James Gibson, who had been missing since leaving Frankston in 1989.

Police quickly confirmed, however, that the bodies were those of Clarke and Walters. Walters had been stabbed 35 times, and Clarke had been shot 10 times in the head.[3] Despite a thorough search of the forest over the following five days, no further evidence or bodies were found by police. Investigators ruled out the possibility of further discoveries within Belanglo State Forest.

Third and fourth discoveries and body identification

In October 1993, a local man, Bruce Pryor, discovered a human skull and thigh bone in a particularly remote section of the forest.[4] He returned with police to the scene and two more bodies were quickly discovered and identified as Deborah Everist and James Gibson.[5] The presence of Gibson's body in Belanglo was a puzzle to investigators as his backpack and camera had previously been discovered by the side of the road at Galston Gorge, in the northern Sydney suburbs over 120 kilometres (75 mi) to the north.[2]

Fifth, sixth and seventh discoveries

On 1 November 1993, a skull was found in a clearing in the forest by police sergeant Jeff Trichter.[6] The skull was later identified as that of Simone Schmidl from Regensburg, Germany.[5] She was last seen hitchhiking on 20 January 1991.[2] Clothing found at the scene was not Schmidl's, but matched that of another missing backpacker, Anja Habschied. Schmidl was found to have died from numerous stab wounds to the upper torso.[7]

The bodies of Habschied and her boyfriend Gabor Neugebauer were found on 3 November 1993 in shallow graves 50 metres (160 ft) apart.[5] Habschied was decapitated,[8] and despite an extensive search, her head could not be found.[7] Neugebauer had been shot in the head 9 times.[7]

Search for the identity of the serial killer

There were similar aspects to all the murders.[9] Each of the bodies had been deliberately posed face-down with their hands behind their backs,[7] covered by a pyramidal frame of sticks and ferns.[9][10] Forensic study determined that each had suffered multiple stab wounds to the torso. The killer had evidently spent considerable time with the victims both during and after the murders, as campsites were discovered close to the location of each body and shell casings of the same calibre were also identified at each site. Joanne Walters and Simone Schmidl had been stabbed, whereas Caroline Clarke and Gabor Neugebauer had been shot numerous times in the head and stabbed post-mortem. Anja Habschied had been decapitated and other victims showed signs of strangulation and severe beatings.[11] Speculation arose that the crimes were the work of several killers,[12] at least two,[13] and later, after the killer was identified, Ivan Milat's sworn statement had suggested anywhere up to seven people were involved.

After developing a profile of the killer, the police faced an enormous volume of data from numerous sources.[14] Investigators therefore applied link analysis technology to Roads and Traffic Authority vehicle records, gym memberships, gun licensing, and internal police records. As a result, the list of suspects was progressively narrowed from an extensive list of individuals to a short list of 230, to an even shorter list of 32, which included the killer.[15]

On 13 November, New South Wales police received a call from Paul Onions in the U.K. Onions had been backpacking in Australia several years before and while out hiking had accepted a ride south out of Sydney from a man known only as "Bill" on 25 January 1990.[16] South of the town of Mittagong, Bill pulled out some ropes attempting to tie the British tourist by the hands and then pulled a gun on Onions, at which point he managed to escape the vehicle while Bill shot at him.[17] Onions flagged down Joanne Berry, a passing motorist, and reported the assault to local police.[18] Onions' statement was backed up by Berry, who also contacted the investigation team, along with the girlfriend of a man who worked with Ivan Milat, who thought he should be questioned over the case. On 13 April 1994, Detective Gordon found the note regarding Paul Onions' call to the hotline five months earlier. Superintendent Clive Small immediately called for the original report from Bowral police but it was missing from their files. Fortunately, Constable Janet Nicholson had taken a full report in her notebook, which provided more details than the original statement. Police confirmed Richard Milat (Ivan's brother) had been working on the day of the attack, but Ivan Milat had not.[19]

Ivan Milat

Arrest

Ivan Milat quickly became a suspect. Police learned he had served prison time and in 1971 had been charged with the abduction of two women and the rape of one of them, although the charges were later dropped.[20] It was also learned that both he and his brother Richard Milat worked together on road gangs along the highway between Sydney and Melbourne, that he owned a property in the vicinity of Belanglo, and had sold a Nissan Patrol four-wheel drive vehicle shortly after the discovery of the bodies of Clarke and Walters.[21] Acquaintances also told police about Milat's obsession with weapons.[22] When the connection between the Belanglo murders and Onions' experience was made, Onions flew to Australia to help with the investigation.

On 5 May 1994, Onions positively identified Ivan Milat as the man who had picked him up and attempted to tie up and possibly murder him.[4] Milat was arrested on 22 May 1994 at his home at Cinnabar Street, Eagle Vale after 50 police officers surrounded the premises, including heavily armed officers from the Tactical Operations Unit.[6][19] Homes belonging to his brothers Richard, Alex, Boris, Walter and Bill were also searched at the same time by over 300 police.[23] The search of Ivan Milat's home revealed a cache of weapons, including parts of a .22 calibre rifle that matched the type used in the murders, plus clothing, camping equipment and cameras belonging to several of his victims.[24]

Milat appeared in court on robbery and weapon charges on 23 May. He did not enter a plea.[7] On 30 May, following continued police investigations, Milat was also charged with the murders of seven backpackers. At the beginning of February 1995, Milat was remanded in custody until June that same year. In March 1996, the trial opened and lasted fifteen weeks.[25] His defence argued that, in spite of the evidence, there was no proof Ivan Milat was guilty and attempted to shift the blame to other members of his family, particularly Richard.[25]

On 27 July 1996, a jury found Ivan Milat guilty of the murders.[6][26] He was also convicted of the attempted murder, false imprisonment and robbery of Paul Onions, for which he received six years' jail each.[16] For the murders of Caroline Clarke, Joanne Walters, Simone Schmidl, Anja Habschied, Gabor Neugebauer, James Gibson and Deborah Everist, Milat was given a life sentence on each count, with all sentences running consecutively and without the possibility of parole.

On his first day in Maitland Gaol, Milat was beaten by another inmate.[27] Almost a year later, he made an escape attempt alongside convicted drug dealer and former Sydney councillor, George Savvas.[28] Savvas was found hanged in his cell the next day and Milat was transferred to the maximum-security super prison in Goulburn, New South Wales.

Appeals

Ivan Milat appealed against his convictions on the grounds that the quality of legal representation he received was poor and therefore constituted a breach of his common law right to legal representation, established in the landmark case of Dietrich v The Queen. However, Gleeson CJ, Meagher JA and Newman J of the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal held that the right to legal representation did not depend on any level or quality of representation, unless the quality of representation were so poor that the accused were no better off with it. The Court found that this was not the case, and therefore dismissed the appeal.[9]

In 2004, Milat filed an application with the High Court which was heard by Justice David Hunt. The orders sought were that Milat be allowed to either attend to make oral submissions in an impending appeal for special leave to the court and that, alternatively, he be allowed to appear via video link. The application was dismissed on the grounds that the issues raised could be adequately addressed by written submission.

The grounds of his impending appeal were that the trial judge had erred by allowing the Crown to put a case to the jury unsupported by its own witnesses and had also put forward alternative cases to the jury, one of which had not been argued by the Crown. McHugh J indicated that this appeal may be defeated because it had been brought out of time.[29]

Self-mutilation in jail

On 26 January 2009, Milat cut off his little finger with a plastic knife,[30] with the intention of mailing the severed digit to the High Court. He was taken to Goulburn Hospital under high security, however, on 27 January 2009, Milat was returned to prison after doctors decided surgery to reattach the finger was not possible.[31]

This was not the first time Milat had injured himself while in prison. In 2001, he swallowed razor blades, staples and other metal objects.[30]

In 2011, Milat went on a hunger strike, losing 25 kilograms in an unsuccessful attempt to be given a PlayStation.[32]

Copycat murder by Milat relative

In 2012, Ivan Milat's great-nephew Matthew Milat and his friend Cohen Klein (both aged 19 at the time of their sentencing) were sentenced to 43 years and 32 years in prison respectively, for murdering David Auchterlonie on his 17th birthday with an axe at the Belanglo State Forest in 2010. Matthew Milat struck with the double-headed axe as Klein recorded the attack with a mobile phone. This was the forest where Ivan Milat had killed and buried his victims.[33][34]

Other developments

Police maintain that Milat may have been involved in many more murders than the seven for which he was convicted. In 2001, Milat was ordered to give evidence at an inquest into the disappearances of three other female backpackers,[35] but no case has been brought against him, due to lack of evidence.[36] Similar inquiries were launched in 2003, in relation to the disappearance of two nurses and again in 2005, relating to the disappearance of hitchhiker Anette Briffa, but no charges have resulted.[37][38]

On 8 November 2004, Ivan Milat gave a televised interview on Australian Story, in which he denied that any of his family had been implicated in the seven murders.[39]

On 18 July 2005, Milat's former lawyer, John Marsden, who had been fired before the murder trial, made a deathbed statement in which he claimed that Milat had been assisted by his sister in the killings of the two British backpackers.[40]

On 7 September 2005, Milat's final appeal was refused,[41] and he is likely to remain in prison for the rest of his life.

In May 2015, Milat's brother Boris told Dr. Steve Aperen, a former homicide detective who serves as a consultant with the LAPD and FBI, among others, that Milat was responsible for another shooting: that of taxi cab driver Neville Knight, in 1962 after Ivan admitted to the crime. After conducting polygraph tests with Boris Milat and Allan Dillon, the man convicted of Knight's shooting, Aperen is convinced that both men are telling the truth and that Ivan Milat did in fact shoot Knight.[42] In May, 2016, it was announced that Milat's former home in Eagle Vale, New South Wales was for sale, and listed on the market for $700,000[43]

In popular culture

The 2005 Australian film Wolf Creek is based on the backpacker murders, among others.

A miniseries on the Seven Network, entitled Catching Milat, was screened in 2015, focusing on the members of "Task Force Air" who tracked Milat during the time of the murders.

References

- ↑ Whittaker, Mark; Kennedy, Les (10 November 2007). Sins of the Brother: The Definitive Story of Ivan Milat and the Backpacker Murders. Pan Macmillan Australia. pp. 267–268, 322. ISBN 978-0-330-36284-9. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Meacham, Steve (24 April 2006). "Friends born of sorrow". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Kennedy, Les (5 September 2010). "Back into heart of darkness". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- 1 2 Brown, Malcolm (2000). Bombs, Guns and Knives: Violent Crime in Australia. Sydney: New Holland. pp. 148–153. ISBN 1-86436-668-0.

- 1 2 3 "The nine bodies found in Belanglo forest". The Australian. AAP. 22 November 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Timeline". Crime & Investigation Network. AETN UK. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Spielman, Peter James (31 May 1994). "Suspect charged in seven murders". The Dispatch. AP. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Thorne, Frank (31 August 2010). "Skull found in hunt for more victims of British girls' killer". Daily Express. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Regina v Milat Matter No Cca 60438/96 (1998) NSWSC 795". AustLII. Supreme Court of New South Wales. 26 February 1998. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ Whittington-Egan, Richard; Whittington-Egan, Molly (18 October 2013). Murder on File. Neil Wilson Publishing. p. 312. ISBN 978-1-906476-53-3. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ Malkin, Bonnie (26 January 2009). "Backpacker killer Ivan Milat cuts off finger in jail". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Hickey, Eric W. (22 July 2003). Encyclopedia of Murder and Violent Crime. SAGE Publications. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-7619-2437-1. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ Maynard, Roger (30 January 2011). "Did Australia's backpacker killer have an accomplice?". The Independent. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Mouzos, Jenny. "Investigating Homicide: New Responses for an Old Crime" (PDF). Australian Institute of Criminology. Australian Government. p. 5. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Mena, Jesús (2011). Machine Learning Forensics for Law Enforcement, Security, and Intelligence. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group). ISBN 978-1-4398-6069-4.

- 1 2 Newton, Michael (1 January 2006). The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. Infobase Publishing. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-0-8160-6987-3. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Oliver, Robin (26 July 2006). "Born to Kill – Ivan Milat". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ Murray, David (31 January 2010). "Backpacker who escaped Ivan Milat to return to Australia". The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- 1 2 Bellamy, Patrick. "Ivan Milat: The Last Ride". TruTV. Time Warner Inc. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "Ivan Milat Biography". The Biography Channel. A+E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Marriott, Trevor (4 September 2013). The Evil Within – A Top Murder Squad Detective Reveals The Chilling True Stories of The World's Most Notorious Killers. John Blake Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-78219-365-4. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Chapman, Simon (2013). Over Our Dead Bodies: Port Arthur and Australia's Fight for Gun Control (PDF). Sydney University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-74332-031-0. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Kidd, Paul B. (1 August 2011). Australia's Serial Killers. Pan Macmillan Australia. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-74262-798-4. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ "Ivan Milat". Crime & Investigation Network. Foxtel. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- 1 2 "The Trial". Crime & Investigation Network. AETN UK. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Walker, Frank (23 May 2004). "Milat's brother claims police still treating him as murder suspect". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ "Skeleton key to unlock Ivan Milat mystery?". Herald Sun. AAP. 30 August 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "Maitland Correctional Centre Escape Attempt". Parliament of New South Wales. 20 May 1997. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "Milat v R [2004] HCA 17; (2004) 205 ALR 338; (2004) 78 ALJR 672 (24 February 2004)". AustLII. 20 April 2004. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- 1 2 "Medics unable to reattach Milat's finger". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ↑ "Serial killer Ivan Milat cuts off finger in High Court protest". News.com.au. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Bashan, Yoni (15 May 2011). "Ivan Milat on hunger strike over Playstation". News.com.au. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ↑ Wells, Jamelle (9 June 2012). "Milat relative gets 30 years for axe murder". ABC News. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Dale, Amy (8 June 2012). "Matthew Milat sentenced to 30 years jail for 'cold blooded' murder". News.com.au. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "Milat linked to 1970s missing persons case". PM. 12 June 2001. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ Connolly, Ellen (5 July 2002). "No peaceful rest". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ Kennedy, Les (8 December 2003). "Milat link to nurses missing since 1980". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ "Milat a suspect in teen's cold-case 'murder'". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 27 January 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ Stewart, John (8 November 2004). "Milat says brothers innocent". ABC News. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ "Milat did not act alone, solicitor says". The 7.30 Report. 19 July 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ "Serial killer's appeal is refused". BBC News. 7 November 2005. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ Lees, Philippa (3 May 2015). "Detective Says 'No Doubt' Over Ivan Milat Claim". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ Aidan Devine (May 1, 2016). "Serial killer Ivan Milat's former Western Sydney home on the market". The Daily Telegraph.

External links

- Article:Milat issues challenge to police boss, By Alex Mitchell, January 25, 2004 in The Age about possible extra inquiries

- Interview with Ivan Milat, 8 November 2004 in ABC-TV's Australian Story.

- Interview:Milat accomplice claim rejected with Clive Small, refuting suppositions that Milat had accomplices, July 16, 2005