Bahram V

| Bahram V 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭 | |

|---|---|

| "King of kings of Iran and Aniran" | |

Gold coin of Bahram V with fire temple on its verso. | |

| Reign | 420–438 |

| Predecessor | Khosrau the Usurper |

| Successor | Yazdegerd II |

| Born | 406[1] |

| Died | 438 |

| Consort | Sapinud |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Yazdegerd I |

| Mother | Shushandukht |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Bahram V (Middle Persian: 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭 Wahrām, New Persian: بهرام پنجم Bahrām) was the fifteenth Sasanian King of Persia (420–438). Also called Bahram Gōr or Bahram Gūr (New Persian: بهرام گور), he was a son of Yazdegerd I (399–420).[2] After his father's assassination, Bahram V gained the crown against the opposition of the grandees by the help of Al-Mundhir I ibn al-Nu'man, the king of the Lakhmid dynasty.

Reign and war with Rome

Bahram V began his reign with a systematic persecution of the Christians. His chief mōbed Mihr-Shabūr ordered Christian tombs and gravesites exhumed.[3] Among those executed (horribly) was James Intercisus, which led to a war with the Eastern Romans.[4]

In the year 421, the Romans sent their general Ardaburius with an extensive contingent into Armenia. Ardaburius defeated the Persian commander Narseh and proceeded to plunder the province of Arzanene and lay siege to Nisibis. Ardaburius abandoned the siege in the face of an advancing army under Bahram, who in turn besieged Theodosiopolis (probably Theodosiopolis in Osroene).

Peace was then concluded between the Persians and Romans (422) with a return to status quo ante bellum.

Relations with Armenia

The situation in Armenia occupied Bahram immediately after the conclusion of peace with Rome. Armenia had been without a king since Bahram's brother Shapur had vacated the country in 418. Bahram now desired that a descendant of the royal line of kings, a scion of the Arshakunis, should be on the throne of Armenia. With this intention in mind, he selected an Arshakuni named Artaxias IV (Artashir IV), a son of Vramshapuh, and made him King of Armenia.[5]

But the newly appointed king did not have a good character. The frustrated nobles petitioned Bahramgur to remove Artaxias IV and admit Armenia into the Persian Empire so that the province would be under the direct control of the Sassanian Empire.[6] However, the annexation of Armenia by Persia was strongly opposed by the Armenian patriarch Isaac of Armenia, who felt the rule of a Christian better than that of a non-Christian regardless of his character or ability. Despite his strong protests, however, Armenia was annexed by Bahram, who placed it under the charge of a Persian governor in 428.[7]

Invasion of the Huns

During the later part of Bahram V's reign, Persia was invaded from the northeast by Hephthalite hordes who ravaged northern Iran under the command of their leader. They crossed the Elburz into Khorasan and proceeded as far as the ancient town of Rey. Unprepared, Bahram initially made an offer of peace and submission which was well received by the Khan of the Hephthalites. But crossing Tabaristan, Hyrcania and Nishapur by night, he took the Huns unawares and massacred them along with their Khan, taking the Khan's wife hostage. The retreating Huns were pursued and slaughtered up to the Oxus. One of Bahram's generals followed the Huns deep into Hun territory and destroyed their power. His portrait which survived for centuries on the coinage of Bukhara (in contemporary Uzbekistan) is considered to be an evidence of his victory over the Huns.

Legacy

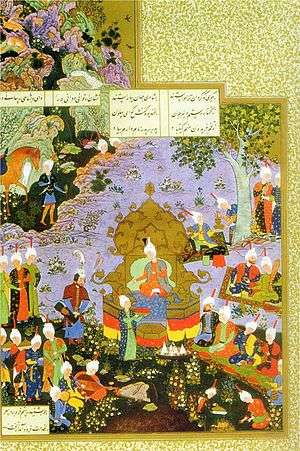

Bahram V has left behind a rich and colorful legacy, with numerous legends and fantastical tales. His fame has survived the downplay of Zoroastrianism and the anti-Iranian measures of the Umayyads and the Mongols, and many of the stories have been incorporated in contemporary Islamic lore.

His legacy even survives outside Iran. He is the king who receives the Three Princes of Serendip in the tale that gave rise to the word Serendipity. He is believed to be the inspiration for the legend of Bahramgur prevalent in the Punjab.

He is a great favourite in Persian tradition, which relates many stories of his valour and beauty; of his victories over the Romans, Hephthalites, Indians, and Africans; and of his adventures in hunting and in love. He is called Bahram Gur, "Onager," on account of his love for hunting, and in particular, hunting onagers.[8]

For example, the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, by Edward Fitzgerald, quatrain 17:

"They say the Lion and the Lizard keep

The Courts where Jamshyd gloried and drank deep:

And Bahram, that great Hunter - the Wild Ass

Stamps o'er his Head, and he lies fast asleep."

To which Fitzgerald adds the following footnote (1st edition, 1859): "Bahram Gur - Bahram of the Wild Ass from his fame in hunting it - a Sassanian sovereign, had also his seven palaces, each of a different colour; each with a Royal mistress within; each of whom recounts to Bahram a romance. The ruins of three of these towers are yet shown by the peasantry; as also the swamp in which Bahram sunk while pursuing his Gur.

Some have judged Bahram V to have been rather a weak monarch, after the heart of the grandees and the priests. He is said to have built many great fire-temples, with large gardens and villages (Tabari).[8]

Coins

The coins of Bahram V are chiefly remarkable for their crude and coarse workmanship and for the number of the mints from which they were issued. The mint-marks include Ctesiphon, Ecbatana, Ispahan, Arbela, Ledan, Nehavend, Assyria, Chuzistan, Media, and Kerman or Carmania. The headdress has the mural crown in front and behind, but interposes between these two detached fragments a crescent and a circle, emblems, no doubt, of the sun and moon gods. The reverse shows the usual fire-altar, with guards, or attendants, watching it. The king's head appears in the flame upon the altar.

Legends

Numerous legends have been associated with Bahram. One account says that he aided an Indian king in his war against China and that, in return for his help, the Indian king made over the provinces of Makran and Sindh to Persia. Other accounts suggest that he married an Indian princess. However, the conclusion of such a marriage alliance is regarded as highly dubious once again due to lack of evidence.

Another legend, found in the Shahnameh, is about Bahram slaying two lions and gaining the crown between them.

Notes

- ↑ Parvaneh Pourshariati, Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire, (I.B. Tauris, 2009), 68.

- ↑ The Oriental Biographical Dictionary, Ed. Thomas William Beale, (Asiatic Society, 1881), 66.

- ↑ Sebastian P Brock (1976). "Christians in the Sasanian Empire: A Case of Divided Loyalties". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. II., 9 n. 37

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ A Fifth Century Hoard of Sasanian Drachms (A.D. 399-460), Hodge Mehdi Malek, Iran, Vol. 33, (1995), British Institute of Persian Studies, 68.

- ↑ Introduction to Christian Caucasian History:II: States and Dynasties of the Formative Period, Cyril Toumanoff, Traditio, Vol. 17, 1961, Fordham University, 6.

- ↑ Simon Payaslian, The History of Armenia:From the Origins to the Present, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 40.

- 1 2

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bahrām". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 211.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bahrām". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 211.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bahram V. |

- Encyclopedia Iranica, "Bahrām V Gōr ", O. Klíma

- Encyclopedia Iranica, "Bahrām V Gōr in Persian Legend and Literature", W. L. Hanaway, Jr

- The Civilizations of the Ancient Near East by George Rawlinson

- Tales of the Punjab by Flora Annie Steel

- Persian Literature in Translation The ackard Humanities Institute: Haft Paikar: TRANSLATED FROM THE PERSIAN,WITH A COMMENTARY, BY C. E. WILSON, B.A. (LOND.)- Romanticized story about Bahram Gur

| Bahram V | ||

| Preceded by Khosrau the Usurper |

Great King (Shah) of Persia 420–438 |

Succeeded by Yazdegerd II |

.png)