Battle of the River Plate

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

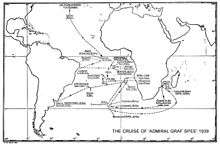

The Battle of the River Plate was the first naval battle in the Second World War and the first one of the Battle of the Atlantic in South American waters. The German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee had been located in the South Atlantic a long time before the war began, and had been commerce raiding after the war began in September 1939. One of the hunting groups sent by the British Admiralty to search for Graf Spee, comprising three Royal Navy cruisers, HMS Exeter, Ajax and Achilles (the last from the New Zealand Division), found and engaged their quarry off the estuary of the River Plate close to the coast of Argentina and Uruguay in South America.

In the ensuing battle, Exeter was severely damaged and forced to retire; Ajax and Achilles suffered moderate damage. The damage to Graf Spee, although not extensive, was critical; her fuel system was crippled. Ajax and Achilles shadowed the German ship until she entered the port of Montevideo, the capital city of neutral Uruguay, to effect urgent repairs. After Graf Spee's captain Hans Langsdorff was told that his stay could not be extended beyond 72 hours, he scuttled his damaged ship rather than face the overwhelmingly superior force that the British had led him to believe was awaiting his departure.[2]

Background

Admiral Graf Spee had been at sea at the start of the Second World War in September 1939, and had sunk several merchantmen in the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic Ocean without loss of life, due to her captain's policy of taking all crews on board before sinking the victim.

The Royal Navy assembled nine forces to search for the surface raider. Force G—the South American Cruiser Squadron—comprised the heavy cruiser HMS Exeter of 8,390 long tons (8,520 t) with six 8 in (200 mm) guns in three turrets, and two Leander-class light cruisers, both of 7,270 long tons (7,390 t) with eight 6 in (150 mm) guns—HMS Ajax and Achilles. Although technically a heavy cruiser because of the calibre of her guns, Exeter was a scaled-down version of the County class, which had eight 8 in (200 mm) guns. The force was commanded by Commodore Henry Harwood from Ajax, which was captained by Charles Woodhouse.[3] Achilles was of the New Zealand Division (precursor to the Royal New Zealand Navy) and captained by Edward Parry. Exeter was commanded by Captain Frederick Secker Bell. A County-class heavy cruiser—HMS Cumberland of 10,000 long tons (10,160 t)—was refitting in the Falkland Islands at the time, but was available at short notice.[4]

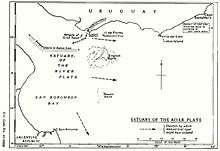

Force G was supported by the oilers RFA Olna, Olynthus, and Orangeleaf. Olynthus replenished HMS Ajax and Achilles on 22 November 1939, and HMS Exeter on 26 November, at San Borombon Bay. Olynthus was also directed to keep observation between Medanos and Cape San Antonio, off Argentina south of the River Plate estuary (see chart below).

Following a raider-warning radio message from the merchantman Doric Star, which was sunk by Graf Spee off South Africa, Harwood suspected that the raider would try to strike next at the merchant shipping off the River Plate estuary between Uruguay and Argentina. He ordered his squadron to steam toward the position 32° south, 47° west. Harwood chose this position, according to his despatch, because of its being the most congested part of the shipping routes in the South Atlantic, and therefore the point where a raider could do the most damage to enemy shipping.[4] A Norwegian freighter saw Graf Spee practising the use of its searchlights and radioed that its course was toward South America.

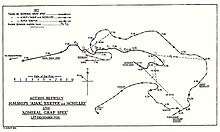

The three cruisers rendezvoused off the estuary on 12 December and conducted manoeuvres. Harwood's combat policy of three cruisers versus one pocket battleship was to attack at once, day or night. If during the day, the ships would attack as two units, with Exeter separate from Ajax and Achilles. If at night, the ships would remain in company, but in open order. By attacking from two sides, Harwood hoped to give his lighter warships a chance of overcoming the German advantage of greater range and heavier broadside by dividing the enemy's fire.[5] By splitting his force, Harwood would force the Germans to split their fire, reducing its effectiveness or by keeping it focused on one opponent, other vessels could attack without fear of return fire.

Although outgunned by Graf Spee and therefore at a tactical disadvantage, the British did have the upper hand strategically since any raider returning to Germany would have to run the blockade of the North Sea and might reasonably be expected to encounter the Home Fleet. For victory, the British only had to damage the raider enough so that she was either unable to make the journey or unable to fight a subsequent battle with the Home Fleet (by contrast the Germans would have to destroy the British force without being severely damaged). Because of overwhelming numerical superiority, the loss of even all three cruisers would not have severely altered Britain's naval capabilities, whereas Graf Spee was one of the Kriegsmarine's few capital ships. The British could therefore afford to risk a tactical defeat if it brought strategic victory.

Battle

On 13 December at 05:20, the British squadron was proceeding on a course of 060° at 14 knots with Ajax at 34° 34′ South 48° 17′ West, 390 nautical miles (720 km) east of Montevideo. At 06:10, smoke was sighted on a bearing of Red-100, or 320° (to the north-west).[6] Admiral Graf Spee had already sighted mastheads and identified Exeter, but initially suspected that the two light cruisers were smaller destroyers and that the British ships were protecting a merchant convoy, the destruction of which would be a major prize. Since Graf Spee′s reconnaissance aircraft was out of service, Langsdorff relied on his lookouts for this information. He decided to engage, despite having received a broadly accurate report from the German naval staff on 4 December, outlining British activity in the River Plate area. This report included information that Ajax, Achilles, Exeter and Cumberland were patrolling the South American coast.

Langsdorff realised too late that he was facing three cruisers. Calling on the immediate acceleration of his diesel engines, he closed with the enemy squadron at 24 kn (28 mph; 44 km/h) in the hope of engaging the steam-driven British ships before they could work up from cruising speed to full power.[7] This strategy may seem an inexplicable blunder: Langsdorff could perhaps have manoeuvred to keep the British ships at a range where he could destroy them with his 283 mm (11.1 in) guns while remaining out of the effective range of their smaller 6- and 8-inch guns. On the other hand, he knew the British cruisers had a 4–6 kn (4.6–6.9 mph; 7.4–11.1 km/h) speed advantage over Graf Spee and could in principle stay out of range should they choose to do so—standard cruiser tactics in the presence of a superior force—while calling for reinforcements.

The British executed their battle plan: Exeter turned north-west, while Ajax and Achilles, operating together, turned north-east to spread Graf Spee′s fire. Graf Spee opened fire on Exeter at 19,000 yd (17,000 m) with her six 283 mm (11.1 in) guns at 06:18. Exeter opened fire at 06:20, Achilles at 06:21, Exeter′s aft guns at 06:22 and Ajax at 06:23. Lieutenant-Commander Richard Jennings,[8] Exeter's gunnery officer remembers:

"As I was crossing the compass platform [to his Action Station in the Director Control Tower], the captain hailed me, not with the usual rigmarole of 'Enemy in sight, bearing etc, but with 'There's the f***ing Scheer! Open fire at her!' Throughout the battle the crew of the Exeter thought they were fighting the [sister ship] Admiral von Scheer. But the name of the enemy ship was of course the Graf Spee".[9]

From her opening salvo, Graf Spee′s gunfire proved fairly accurate, her third salvo straddling Exeter. At 06:23, a 283 mm (11.1 in) shell burst just short of Exeter, abreast the ship. Splinters from this shell killed the torpedo tubes' crews, damaged the ship's communications, riddled the ship's funnels and searchlights and wrecked the ship's Walrus aircraft, just as it was about to be launched for gunnery spotting. Three minutes later, Exeter suffered a direct hit on her "B" turret, putting it and its two guns out of action.[10] Shrapnel swept the bridge, killing or wounding all bridge personnel except the captain and two others. Captain Bell's communications were wrecked. Communications from the aft conning position were also destroyed; the ship had to be steered via a chain of messengers for the rest of the battle.

Meanwhile, Ajax and Achilles closed to 13,000 yd (12,000 m) and started making in front of Graf Spee, causing her to split her main armament at 06:30 and otherwise use her 15 cm (5.9 in) guns against them. Shortly after, Exeter fired two torpedoes from her starboard tubes but both missed. At 06:37, Ajax launched her Fairey Seafox spotter floatplane from its catapult. At 06:38, Exeter turned so that she could fire her port torpedoes and received two more direct hits from 11 in (280 mm) shells. One hit "A" turret and put it out of action, the other entered the hull and started fires. At this point, Exeter was severely damaged, having only "Y" turret still in action under 'local' control, with Jennings on the roof shouting instructions to those inside.[11] She also had a 7° list, was being flooded and being steered with the use of her small boat's compass. However, Exeter dealt the decisive blow; one of her 8 in (200 mm) shells had penetrated two decks before exploding in Graf Spee′s funnel area, destroying her raw fuel processing system and leaving her with just 16 hours fuel, insufficient to allow her to return home.

At this point, nearly one hour after the battle started, Graf Spee was doomed; she could not make fuel system repairs of this complexity under fire. Two-thirds of her anti-aircraft guns were knocked out, as well as one of her secondary turrets. There were no friendly naval bases within reach, nor were any reinforcements available. She was not seaworthy and could make only the neutral port of Montevideo.[12]

Admiral Graf Spee hauled round from an easterly course, now behind Ajax and Achilles, towards the north-west and laid smoke. This course brought Langsdorff roughly parallel to Exeter. By 06:50, Exeter listed heavily to starboard, taking water forward. Nevertheless, she still steamed at full speed and fired with her one remaining turret. Forty minutes later, water splashed in by a 283 mm (11.1 in) near-miss short-circuited her electrical system for that turret. Captain Bell was forced to break off the action. This would have been the opportunity to finish off Exeter. Instead, the combined fire of Ajax and Achilles drew Langsdorff's attention as both ships closed the German ship.[13]

Twenty minutes later, Ajax and Achilles turned to starboard to bring all their guns to bear, causing Admiral Graf Spee to turn away and lay a smoke screen. At 07:10, the two light cruisers turned to reduce the range from 8 mi (7.0 nmi; 13 km), even though this meant that only their forward guns could fire. At 07:16, Graf Spee turned to port and headed straight for the badly damaged Exeter, but fire from Ajax and Achilles forced her at 07:20 to turn and fire her 11 in (280 mm) guns at them, while they turned to starboard to bring all their guns to bear. Ajax turned to starboard at 07:24 and fired her torpedoes at a range of 4.5 mi (3.9 nmi; 7.2 km), causing Graf Spee to turn away under a smoke screen. At 07:25, Ajax was hit by a 283 mm (11.1 in) shell that put "X" turret out of action and jammed "Y" turret, causing some casualties. By 07:40, Ajax and Achilles were running low on resources, and the British decided to change tactics, moving to the east under a smoke screen. Harwood decided to shadow Graf Spee and try to attack at night, when he could attack with torpedoes and better use his advantages of speed and manoeuvrability, while minimising his deficiencies in armour. Ajax was again hit by a 283 mm (11.1 in) shell that destroyed her mast and caused more casualties; Graf Spee continued to the south-west.

Pursuit

The battle now turned into a pursuit. Captain Parry of Achilles wrote afterwards: "To this day I do not know why the Admiral Graf Spee did not dispose of us in the Ajax and the Achilles as soon as she had finished with the Exeter".[8] The British and New Zealand cruisers split up, keeping about 15 mi (13 nmi; 24 km) from Graf Spee. Ajax kept to the German's port and the Achilles to the starboard. At 09:15, Ajax recovered her aircraft. At 09:46, Harwood signalled to the Cumberland for reinforcement and the Admiralty also ordered ships within 3,000 mi (2,600 nmi; 4,800 km) to proceed to the River Plate. At 10:05, Achilles had overestimated Graf Spee′s speed and she came into range of the German guns. Graf Spee turned and fired two three-gun salvoes with her fore guns. Achilles turned away under a smoke screen.

According to Pope, at 11:03 a merchant ship was sighted close to Graf Spee.[8] After a few minutes, Graf Spee called Ajax on W/T, probably on the international watchkeeping frequency of 500 kHz, using both ships' pre-war call-signs, with the signal: "please pick up lifeboats of English steamer". The German call-sign was DTGS, confirming to Harwood that the pocket-battleship he had engaged was indeed Graf Spee. Ajax did not reply but a little later the British flagship closed with SS Shakespeare with its lifeboats still hoisted and men still on board. Graf Spee had fired a gun and ordered them to stop but when they did not obey orders to leave the ship, Langsdorff decided to continue on his way and Shakespeare had a lucky escape. The shadowing continued for the rest of the day until 19:15, when Graf Spee turned and opened fire on Ajax, which turned away under a smoke screen.

It was now clear that Graf Spee was entering the River Plate estuary. Since the estuary had sandbanks, Harwood ordered the Achilles to shadow the Graf Spee while Ajax would cover any attempt to double back through a different channel. The sun set at 20:48, with Graf Spee silhouetted against the sun. Achilles had again closed the range and Graf Spee opened fire, forcing Achilles to turn away. During the battle, a total of 108 men had been killed on both sides, including 36 on Graf Spee.

Graf Spee entered Montevideo in neutral Uruguay, dropping anchor at about 00:10 on 14 December. This was a political error, since Uruguay, while neutral, had benefited from significant British influence during its development and it favoured the Allies. The British Hospital, for example (where the wounded from the battle were taken), was the leading hospital in the city. The port of Mar del Plata on the Argentine coast and 200 mi (170 nmi; 320 km) south of Montevideo would have been a better choice for Graf Spee.[14] Also, had Graf Spee left port at this time, the damaged Ajax and Achilles would have been the only British warships that it would encounter in the area.

Trap of Montevideo

In Montevideo, the 13th Hague Convention came into play. Under Article 12, "...belligerent war-ships are not permitted to remain in the ports, roadsteads or territorial waters of the said Power for more than twenty-four hours...", modified by Article 14 "A belligerent war-ship may not prolong its stay in a neutral port beyond the permissible time except on account of damage..." British diplomats duly pressed for the speedy departure of the Graf Spee. Also relevant was Article 16, of which part reads, "A belligerent war-ship may not leave a neutral port or roadstead until twenty-four hours after the departure of a merchant ship flying the flag of its adversary."[15]

The Germans released 61 captive British merchant seamen who had been on board in accordance with their obligations. Langsdorff then asked the Uruguayan government for two weeks to make repairs. Initially, the British diplomats in Uruguay—principally Eugen Millington-Drake—tried to have Admiral Graf Spee forced to leave port immediately. After consultation with London, which was aware that there were no significant British naval forces in the area, Millington-Drake continued to demand openly that Graf Spee leave. At the same time, the British secretly arranged for British and French merchant ships to steam from Montevideo at intervals of 24 hours, whether they had originally intended to do so or not, thus invoking Article 16. This kept Graf Spee in port and allowed more time for British forces to reach the area.

At the same time, efforts were made by the British to feed false intelligence to the Germans that an overwhelming British force was being assembled, including Force H (the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal and the battlecruiser HMS Renown), when in fact only the heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland was nearby. Cumberland—one of the earlier County class cruisers—was only a little more powerful than Exeter, with two more 8 in (200 mm) guns. She was no match alone for Admiral Graf Spee, whose guns had significantly longer range and fired much heavier shells. Cumberland arrived at 22:00 on 14 December, after steaming at full speed for 36 hours from the Falkland Islands. Overwhelming British forces (HMS Renown, Ark Royal, Shropshire, Dorsetshire, and Neptune) were en route, but would not assemble until 19 December. For the time being, the total force comprised the undamaged Cumberland, and the damaged Ajax and Achilles. To reinforce the propaganda effect, these ships — which were waiting just outside the three-mile limit — were ordered to make smoke, which could be clearly seen from the Montevideo waterfront.

On 15 December 1939, RFA Olynthus refuelled HMS Ajax, which proved a difficult operation; the ship had to use hurricane hawsers to complete the replenishment. On 17 December HMS Achilles was replenished from RFA Olynthus off Rouen Bank.

The Germans were entirely deceived, and expected to face a far superior force on leaving the River Plate. Graf Spee had also used two-thirds of her 283 mm (11.1 in) ammunition and had only enough left for approximately a further 20 minutes of firing, which was hardly sufficient to fight her way out of Montevideo, let alone getting back to Germany.

While the ship was prevented from leaving the harbour, Captain Langsdorff consulted with his command in Germany. He received orders that permitted some options, but not internment in Uruguay. The Germans feared that Uruguay could be persuaded to join the Allied cause. Ultimately, he chose to scuttle his ship in the River Plate estuary on 17 December, to avoid unnecessary loss of life for no particular military advantage, a decision that is said to have infuriated Adolf Hitler. The crew of Admiral Graf Spee were taken to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where Captain Langsdorff committed suicide by gunshot on 19 December. He was buried there with full military honours, and several British officers who were present attended. Many of the crew members were reported to have moved to Montevideo with the help of local people of German origin. The German dead were buried in the Cementerio del Norte, Montevideo.

Aftermath

The German propaganda machine had reported that Admiral Graf Spee had sunk a heavy cruiser and heavily damaged two light cruisers while only being lightly damaged herself. Graf Spee's scuttling however was a severe embarrassment and difficult to explain on the basis of publicly available facts. The battle was a major propaganda victory for the British during the Phoney War, as the damage to Ajax and Achilles was not sufficient to reduce their fighting efficiency, while Exeter, as badly damaged as she was, was able to reach the Falkland Islands for emergency repairs, before returning to Devonport for a 13-month refit, thus enhancing the reputation of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill.

A great deal has been made of the point Langsdorff was 'tricked' by the British but the truth of the matter was that, with the damage to his ship and the bulk of his ammunition expended, even if he fought past the British cruisers into the open sea, he had nowhere to go. There was no friendly port where he could get serious repairs outside Germany, and there was very little chance of getting his ship that far.

Prisoners taken from merchant ships by Admiral Graf Spee who had been transferred to her supply ship Altmark were freed by a boarding party from the British destroyer HMS Cossack, in the Altmark Incident (16 February 1940)—whilst in Jøssingfjord, at the time neutral Norwegian waters. Prisoners who had not been transferred to Altmark had remained aboard Graf Spee during the battle; they were released on arrival in Montevideo.

On 22 December 1939 over 1,000 sailors from Graf Spee were taken to Buenos Aires and interned there; at least 92 were transferred during 1940 to a camp in Rosario, some were transferred to Club Hotel de la Ventana in Buenos Aires Province and another group to Villa General Belgrano, a small town founded by German immigrants in 1932. Some of these sailors later settled there.[16] There are many stories, but little reliable information, about their later wartime activities, including escapees illegally returning to the German armed forces, espionage, and clandestine German submarine landings in Argentina. After the war many German sailors settled permanently in various parts of Uruguay, some returning after being repatriated to Germany. Rows of simple crosses in the Cementerio del Norte, in the north of the city of Montevideo, mark the burial places of the German dead. Three sailors killed aboard Achilles were buried in the British Cemetery in Montevideo, while those who died on Exeter were buried at sea.

Plans to raise the wreck are discussed in the article on Admiral Graf Spee.

Intelligence gathering and salvage

Immediately after her scuttling, the wreck of Admiral Graf Spee rested in shallow water, with much of the ship's superstructure remaining above water level, but over the years, the wreck has subsided into the muddy bottom and today only the tip of the mast remains above the surface.

A radar expert was sent to Montevideo shortly after the scuttling and reported a rotating aerial, probably for gunlaying, transmitting on either 57 or 114 centimetres.[17] In February 1940, the wreck was boarded by US Navy sailors from the light cruiser USS Helena.

In 1964 a memorial to the ship was erected in Montevideo's port. Part of it is the Graf Spee's anchor.[18]

In 1997, one of Admiral Graf Spee′s 15 cm (5.9 in) secondary gun mounts was raised and restored; it can now be seen outside Montevideo's National Maritime Museum.

In February 2004, a salvage team began work raising the wreck. The operation is being funded in part by the government of Uruguay, in part by the private sector, as the wreck is now a hazard to navigation. The first major section, the 27 long tons (27 t) heavy gunnery control station, was raised on 25 February 2004. It is expected to take several years to raise the entire wreck. The director James Cameron is filming the salvage operation. After it has been raised, it is planned that the ship will be restored and put on display at the National Marine Museum.

Many German veterans do not approve of this restoration attempt, as they consider the wreck to be a war grave and an underwater historical monument that should be respected. One of them, Hans Eupel, a former specialist torpedo mechanic, 87 years old in 2005, said that "this is madness, too expensive and senseless. It is also dangerous, as one of the three explosive charges we placed did not explode."[19]

On 10 February 2006, the 2 m (6 ft 7 in), 400 kg eagle and swastika crest of Admiral Graf Spee was recovered from the stern of the ship.[20] This spread-wing statue of a Nazi eagle with a wreath in its talons containing a swastika was attached to the stern, not the bow like traditional figureheads. It was a common feature of prewar Nazi warships. In other cases, it was removed for a variety of practical reasons on the outbreak of the war, but because Graf Spee was already at sea when the war began, she went into action (and was scuttled) with it attached, thus permitting its recovery. To protect the feelings of those with painful memories of Nazi Germany, the swastika at the base of the figurehead was covered as it was pulled from the water. The figurehead was stored in a Uruguayan naval warehouse following German complaints about exhibiting "Nazi paraphernalia".[21]

Legacy

In 1956, the film The Battle of the River Plate (US title: Pursuit of the Graf Spee) was made of the battle and Admiral Graf Spee's end, with Peter Finch as Langsdorff. Finch portrayed Langsdorff authentically as a gentleman. HMNZS Achilles, which had been recommissioned in 1948 as HMIS Delhi, flagship of the Royal Indian Navy, played herself in the film. HMS Ajax was "played" by HMS Sheffield, HMS Exeter by HMS Jamaica and HMS Cumberland by herself. Graf Spee was portrayed by the U.S. heavy cruiser USS Salem.

The battle was for many years re-enacted with large-scale model boats throughout the summer season at Peasholm Park in the British seaside resort of Scarborough. The re-enactment now portrays an anonymous battle between a convoy of British ships and an unspecified enemy in possession of the nearby shore.[22]

After the battle, the new town of Ajax, Ontario in Canada, constructed as a Second World War munitions production centre, was named after HMS Ajax. Many of its streets are named after Admiral Harwood's crewmen on Ajax, Exeter and Achilles.[23] Its main street is named after Admiral Harwood.

A number of streets in Nelson Bay, New South Wales, have been named after the battle including Montevideo Pde, Achilles St, Ajax Ave, Harwood Ave, Exeter Rd (now called Shoal Bay Rd). In Auckland, home port for the Royal New Zealand Navy, streets have been named for Achilles, Ajax and Exeter.

The names of the ships, and the commander of Force G, have also been used for the Cadet Corps. The Royal Canadian Sea Cadet Corps (RCSCC) Ajax No. 89 in Guelph, Ontario; the Navy League Cadet Corps (NLCC) Achilles No. 34 in Guelph, Ontario; the Navy League Wrenette Corps (NLWC) Lady Exeter (now disbanded) and the camp shared by all three corps, called Camp Cumberland (this camp no longer exists; it was decommissioned around 1999). RCSCC Harwood No. 244 and NLCC Exeter No. 173 are situated in Ajax, Ontario. According to an article in the German language paper Albertaner on 6 October 2007, a street in Ajax, Ontario, was named after Captain Langsdorff, despite protests by some Canadian veterans. Steve Parish, the mayor of Ajax, defended the decision, declaring that Langsdorff had not been a typical Nazi officer. An accompanying photograph (seen left) from the funeral shows Langsdorff paying tribute with a traditional naval salute, while people beside and behind him—even some clergymen—are giving the Fascist salute. The picture is credited to Diego Lascano (Gilby Collection).

The battle is also significant as it was the first time the current Flag of New Zealand was flown in battle, from HMS Achilles.[24]

References

- ↑ O'Hara 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ Churchill 1948, pp. 525–526.

- ↑ Churchill 1948, p. 516

- 1 2 Churchill 1948, p. 519

- ↑ Barnett, 83.

- ↑ Battle Report

- ↑ Barnett, 84.

- 1 2 3 Dudley Pope (1956), The Battle of the River Plate, Chatham Publishing, UK, 1999, ISBN 1-86176-089-2 p. ix

- ↑ Arthur, Max – Forgotten Voices of The Second World War , 2004, Random House, ISBN 0091897343 p.29

- ↑ Churchill 1948, p. 520

- ↑ Arthur, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Maier, Rohde, Stegemann and Umbreit 1991, p. 166.

- ↑ Barnett, 85.

- ↑ Millington-Drake, Eugen: The Drama of Graf Spee and the Battle of the Plate: A Documentary Anthology, 1914–1964. P. Davies, 1965. pp. 226 and 228

- ↑ "The Avalon Project: Text of the 13th Hague Convention".

- ↑ Archived 1 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Johnson, Brian. The Secret War, BBC 1979, pp. 101–102 ISBN 0-563-17769-1

- ↑ Anchor of the Graf Spee, Montivideo

- ↑ Rohter, Larry (25 August 2006). "A Swastika, 60 Years Submerged, Still Inflames Debate". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ↑ "Graf Spee's eagle rises from deep". BBC News. 10 February 2006. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ↑ "What should Uruguay do with its Nazi eagle?". BBC News. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ↑ "Friends of Peasholm Park".

- ↑ "The Second World War created Ajax. Here's how".

- ↑ "The "Diggers' " flag, the New Zealand Ensign, flying at the masthead of Achilles during the naval battle". Papers Past. 23 February 1940. p. Page 9. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

Bibliography

- Churchill, Winston (1948). The Second World War: The Gathering Storm. I (1st ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Dick, Enrique. (2014) In the Wake of the Graf Spee. Billerica, MA: WIT Press. ISBN 978-1-84564-932-6

- Hayes, James (producer & director), Battle of the River Plate, episode 24.2 (2006) of Timewatch, BBC

- Maier, Klaus; Rohde, Horst; Stegemann, Bernd; Umbreit, Hans. (1991) Germany and the Second World War: Germany's initial conquests in Europe. Clarendon, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-822885-6

- O'Hara, Vincent (2004). The German fleet at war, 1939–1945. Naval Institute Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of the River Plate. |

- History learning site articles with much detail on The Battle of the River Plate and Admiral Graf Spee in Montevideo

- Jilani, Capt (Retd) AA (December 1999). "The Battle of the River Plate". Defence Journal. Archived from the original on 23 February 2003.

- Official HMSO report

- Royal New Zealand Navy (official history)

- Achilles at the River Plate (official history)

- (Spanish) "The crew of the Graf Spee" – Largely anecdotal information on activities of the interned crew after the battle.

- Laurence, Ricardo E. (2000). Tripulantes del Graf Spee en tres atrapantes historias (in Spanish). Rosario: Edición del Autor. ISBN 987-43-1754-X.

- 13th Hague Convention (Convention Concerning the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers in Naval War)

- Battle of the River Plate (NZHistory.net.nz)

- Memorial to those lost

Coordinates: 32°S 47°W / 32°S 47°W

.jpg)