Bicycle helmets in New Zealand

Bicycle helmets have been mandatory in New Zealand since January, 1994.[1] The statute, delineated in Part 11 of the Land Transport (Road User) Rule 2004 (SR 2004/427), states that "A person must not ride, or be carried on, a bicycle on a road unless the person is wearing a safety helmet of an approved standard that is securely fastened." The law describes six different acceptable helmet standards.[2]

Violating the law can result in a $55 infringement fee and a maximum $1,000 penalty on summary conviction.[3]

Exemptions to the law may be granted on "grounds of religious belief or physical disability or other reasonable grounds."[2] 58 of 69 applications for exemption were granted prior to 2000.[4]

Reportedly between 6000 and 10000 cyclists a year are stopped and fined by police for riding without a helmet.[5]

A 2011 survey by the New Zealand Ministry of Transport found the national cycle helmet wearing rate, covering all age groups, to be 93%, the same as found in 2010 and comparable to the 92% rate seen in 2007–2009.[6]

History

The mandatory helmet law had its genesis in the late 1980s when Rebecca Oaten, dubbed the "helmet lady" in the media, started a campaign advocating for compulsory helmets. Her son, Aaron, had been permanently brain damaged in 1986 while riding his 10-speed bicycle to school in Palmerston North. A car driver hit him, flinging Aaron over the handlebars and headfirst to the ground,[7] where his head struck the concrete gutter. After 8 months in a coma, Aaron awoke paralysed and unable to speak.[8] According to Oaten, a doctor at the time told her that Aaron would "almost certainly not have suffered brain damage" had he been wearing a bicycle helmet.[9]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s Oaten travelled the country promoting the use of cycle helmets. For six years she visited an average of four schools a day, "lambasting" children with reasons why they should wear helmets.[10] She also set up a lobby group, the Protect the Brains trust, which spread nationwide and put pressure on the government for a bicycle helmet law.[8]

Oaten's campaigning is commonly perceived as the main impetus for the law compelling all ages of people on bicycles to wear helmets. Aaron Oaten died on 14 August 2010, aged 37.[7][8]

Following Oaten's campaigning, the then Transport Minister introduced helmet legislation without debate in Parliament or select committee hearing. This lack of process in legislation and subsequent effects (or lack thereof) has led commentators to label New Zealand's helmet legislation (and its Australian equivalent) a 'failed experiment'.[11]

Research

Research on the helmet law's effects in New Zealand has failed to identify any clear, consistent benefit to cyclists or the population as a whole.

A 1999 study concluded that "the helmet law has been an effective road safety intervention that has led to a 19% (90% CI: 14, 23%) reduction in head injury to cyclists over its first 3 years."[13]

In a study by the Ministry of Transport published in 1999, researchers estimated that from 1990 to 1996, that the increase in helmet-wearing after passage of the law "reduced head injuries by between 24 and 32% in non-motor vehicle crashes, and by 20% in motor vehicle crashes."[14]

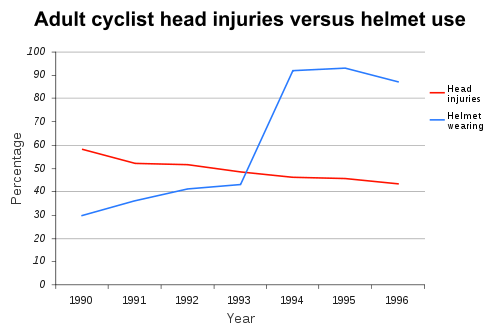

A 2001 study by Robinson re-evaluated that data, finding that the reduction in head injuries per limb injuries, for crashes not involving motor vehicles injuries, was part of a larger downward time trend and bore no direct correlation to the dramatic increase in helmet-wearing following the introduction of the helmet law. Robinson concluded: "Because the large increases in wearing with helmet laws have not resulted in any obvious change over and above existing trends, helmet laws and major helmet promotion campaigns are likely to prove less beneficial and less cost effective than proven road-safety measures." See Figure 1.[12]

A 2002 study by Taylor and Scuffham, which assessed the cost of the New Zealand helmet law against hospital admissions averted and the 'social' costs of debilitating head injury, but did not include the costs associated with fatalities or potentially lifelong health care, found that the law is only cost-effective for the 5- to 12-year-old age group and that large costs from the law were imposed on adult (>19 years) cyclists.[15] Taylor and Scuffham cautioned that "the social costs saved due to fewer head injuries are likely to understate the true costs... our estimates of the net benefit from helmet wearing are likely to be understated".

Research from Massey University in 2006 found that compulsory bicycle helmet laws led to a lower uptake of cycling, principally for aesthetic reasons.[16]

A 2010 study found a declining trend in the rate of traumatic brain injuries among cyclists from 1988-91 to 1996-99. "However, it is unclear whether this reflects the effectiveness of the mandatory all-age cycle helmet law implemented in January 1994 or simply reflects a general decline in all road injuries during that period."[17] The same study noted that "Of particular concern are children and adolescents who have experienced the greatest increase in the risk of cycling injuries despite a substantial decline in the amount of cycling over the past two decades." and that "The "safety in numbers" phenomenon suggests that the risk profile of cyclists may improve if more people cycle. In New Zealand, the overall travel mode share for cycling declined steadily from 4% in 1989 to 1% in 2006."

A study by Clarke published in the New Zealand Medical Journal in 2012 reported that "pre-law (in 1990) cyclist deaths were nearly a quarter of pedestrians in number, but in 2006–09, the equivalent figure was near to 50% when adjusted for changes to hours cycled and walked," a 20% higher risk per hour of bicycle use. The paper "finds the helmet law has failed in aspects of promoting cycling, safety, health, accident compensation, environmental issues and civil liberties."[18] A 2013 conference paper by Wang et al.[19] argues 'due to weakness in the analysis and choice of data – particularly the four-year absence of data around the time helmet laws were introduced' that Clarke's conclusion is 'highly questionable if not misleading'. Clarke replied with additional information supporting his findings.[20]

Australian journalist Chris Gillham [21] compiled an analysis of data from Otago University and the Ministry of Transport, showing a marked decline in cycling participation immediately following the helmet law introduction in 1994. At the same time as the number of cyclists aged over 5 years approximately halved, the injury rate approximately doubled. Noting both the decline in numbers and increase in injury rate preceded the law's introduction at the start of 1994, possibly attributable to the fact that heavy promotion of helmets had been ongoing in the lead-up to the law's introduction. This phenomenon of just helmet promotion leading to a reduction in cycling has been witnessed in several countries.[22] See Figure 2.

Advocacy and caution

Safekids New Zealand, a national child injury prevention service, promotes helmet-wearing by children with a factsheet detailing bicycle injury statistics.[23]

The state insurance agency, the Accident Compensation Corporation, offers a manual for community injury-prevention projects that mentions the importance of children wearing helmets.[24]

The NZ Ministry of Transport[25] claims that helmets reduce the risk of brain injury by "up to 88%". This figure derives from an American research paper from the 1980s and has been questioned.[26]

National advocacy group Cycling Advocates' Network (CAN) "fully supports the use of helmets when undertaking recreational cycling in difficult terrain or high-speed competitive racing" but supports further research on the helmet law's effectiveness, finding evidence that "mandatory cycle helmet wearing legislation is not working as intended and should be reviewed." Such research is not currently a high priority for the group, and in a poll of its members, CAN noted an even split for and against helmet legislation, but helmet legislation was members' lowest campaigning priority.[27]

New Zealand cycling organization BikeNZ reminds riders that helmets are legally required and says helmets "can reduce the severity of injuries in many types of accident" but can't be relied on exclusively and should be part of an overall cycling safety regimen.[28]

Cycling Health New Zealand does not oppose helmet use, but does oppose compulsion, taking a civil liberties stance on the issue: "Individuals should have the right to choose whether or not to use a helmet, without interference by Governments. We believe that the role of Government should be limited to advising the public, without bias, of the pros and cons of helmet use."[29]

A recent analysis of all fatalities to cyclists on roads or pathways in New Zealand for the years 2006-2012 discussed helmet wearing: “Only nine (of the 84) victims were noted as not wearing a helmet, similar to current national helmet‐wearing rates (92%). This highlights the fact that helmets are generally no protection to the serious forces involved in a major motor vehicle crash; they are only designed for falls... There is a suspicion that some people (children in particular) have been “oversold” on the safety benefits of their helmet and have been less cautious in their riding style as a result.”[30][31]

Government response

In response to the formation of Cycling Health New Zealand[29] in January 2003 a Land Transport Safety Authority (LTSA) spokesman called helmets a "very important tool" for preventing injuries and dismissed the anti-compulsion group as "the lunatic fringe",[32] a comment denounced by CAN, urging the LTSA to "play the ball and not the person."[33] In June 2004 an LTSA spokesperson stated, "I think the vast majority of people accept the fact that helmets protect them. There is no evidence that the helmet law discourages cycling or harms the health of New Zealanders - there is evidence that it has contributed to a reduction in cyclist head injuries."[4]

In October 2008, Minister for Transport Safety Harry Duynhoven pondered, "I wonder if we never had helmets what our cycle population might be... I'm not advocating getting rid of helmets, I'm just saying I wonder what the social effect of helmets has been."[34]

See also

- Cycling in New Zealand

- Transport in New Zealand

- History of cycling in New Zealand

- Bicycle helmet laws by country

References

- ↑ "Helmet Laws for Bicycle Riders" Retrieved 2012-02-04

- 1 2 "New Zealand Land Transport (Road User) Rule 2004(SR 2004/427)" Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ↑ "Land Transport (Offences and Penalties) Regulations 1999 (SR 1999/99) (as at 20 October 2011)" Retrieved 2012-02-06

- 1 2 Dearnaley, Mathew "Cycling advocate ends his helmet headache", The New Zealand Herald. 2 June 2004. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Cycle safe: 10,000 fined for no helmet, some get speeding tickets. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11185288

- ↑ http://www.transport.govt.nz/research/Cyclehelmetuse2011/[] Cycle helmet use: Results of national survey, March/April 2011 Retrieved 2012-02-04

- 1 2 Price, Christel. "The legacy of a life", The Guardian (Manawatu), 26 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Duff, Michelle (17 August 2010). "Aaron's tragedy spurred Helmet Lady's crusade". Manawatu Standard. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Mullins, Justin."Hard-Headed Choice", New Scientist, 22 July 2000. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ Kennett, Jonathan (2004). Ride: The Story of Cycling in New Zealand. Wellington: Kennett Brothers. p. 216. ISBN 0-9583490-7-X.

- ↑ Turner, Luke (April 2012). "Australia's helmet law disaster". Institute of Public Affairs. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- 1 2 Robinson, D.L (2001). "Changes in head injury with the New Zealand bicycle helmet law". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 33 (5): 687–91. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(00)00073-7. PMID 11491251.

- ↑ Scuffham, Paul; Alsop, Jonathan; Cryer, Colin; Langley, John D. (2000). "Head injuries to bicyclists and the New Zealand bicycle helmet law". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 32 (4): 565–73. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00081-0. PMID 10868759.

- ↑ Povey, L.J.; Frith, W.J.; Graham, P.G. (1999). "Cycle helmet effectiveness in New Zealand". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 31 (6): 763–70. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00033-0. PMID 10487351.

- ↑ Taylor, M; Scuffham, P (2002). "New Zealand bicycle helmet law--do the costs outweigh the benefits?". Injury Prevention. 8 (4): 317–20. doi:10.1136/ip.8.4.317. PMC 1756574

. PMID 12460970.

. PMID 12460970. - ↑ "Dump harmful helmet law, say cyclists" (Press release). Cycling Health. December 13, 2006. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ↑ Tin Tin, Sandar; Woodward, Alistair; Ameratunga, Shanthi (2010). "Injuries to pedal cyclists on New Zealand roads, 1988-2007". BMC Public Health. 10: 655. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-655. PMC 2989960

. PMID 21034490.

. PMID 21034490. - ↑ Clarke, Colin (2012). "Evaluation of New Zealand's bicycle helmet law". New Zealand Medical Journal. 125 (1349).

- ↑ Wang, J.J.J.; Grzebieta, R.; Walter, S.; Olivier, J. "An evaluation of the methods used to assess the effectiveness of mandatory bicycle helmet legislation in New Zealand" (PDF). 2013 Australasian College of Road Safety Conference.

- ↑ Clarke, Colin (2014). "Reply to Wang et al response to 'Evaluation of New Zealand's bicycle helmet law' article". New Zealand Medical Journal. 127 (1402).

- ↑ http://www.cycle-helmets.com/zealand_helmets.html

- ↑ http://www.cyclehelmets.org/1020.html

- ↑ Safekids "Factsheet: Child Cyclist Injury", July 2007. Retrieved 2013-05-3.

- ↑ ACC. "Preventing injuries in your community", ACC5209, 28 Apr 2010, Accident Compensation Corporation, p.7. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ Ministry of Transport "Cyclists: Crash Factsheet 2010", Sep 2010. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- ↑ BHRF. Why it is wrong to claim that cycle helmets prevent 85% of head injuries and 88% of brain injuries.

- ↑ "CAN and Cycle Helmet Legislation" Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ BikeNZ. "Road Rules" Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2012-02-06.

- 1 2 "Cycling Health New Zealand" Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- ↑ Koorey, G.F., 2013. New Zealand Chief Coroner’s Inquiry into Cycling Deaths – Evidence. Available at: can.org.nz/system/files/CoronerInquest-Notes-GKoorey-v2.4-Jun2013.pdf

- ↑ Koorey (2013). "Investigating common trends in New Zealand cycling fatalities". Injury Prevention. 18(Suppl 1): A221.

- ↑ Lowe, Matthew (19 Jan 2003). "'Ridiculous' helmet law under fire". Sunday Star-Times. Retrieved 2011-01-31. (Note: The original article is no longer online. The link is to an issue of CAN's e.CAN newsletter which includes the article verbatim.)

- ↑ "Helmet Law Concerns Are Legitimate, Say Cyclists" (Press release). Cycling Advocates Network. January 22, 2003. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ↑ Williamson, Kerry (23 Oct 2008). "Helmets 'may be deterring cyclists'". The Dominion Post. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

External links

- Cycling Health - a New Zealand group promoting removal of the compulsory bicycle helmet law.

- New Zealand Helmet Wars - a 2002 article from Safekids NZ in support of the helmet law.

- Land Transport (Road User) Rule 2004 - the wording of New Zealand's bicycle helmet law.

- Mandatory bicycle helmet laws in New Zealand - summary of New Zealand's bicycle helmet law and its effects.