Black people and Mormonism

Gladys Knight has sought to raise awareness of black people in the LDS Church.

From the mid-1800s until 1978, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) had a policy which prevented most men of black African descent from being ordained to the church's lay priesthood. Black members were also not permitted to participate in most temple ordinances. These views influenced views on civil rights.[1]:46-48 During the mid-1800s, president of the church Brigham Young held the position that slavery was a "divine institution, and not to be abolished until the curse pronounced on Ham shall have been removed from his descendants,"[2] (though abuse was condemned).[3] Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, during his 1844 campaign for president of the United States had advocated for the immediate abolition of slavery through compensation from money earned by the sale of public lands.[4][5]

After Smith's death, Young taught that black suffrage went against doctrine,[6] that God had taken away the rights for blacks to hold public office[7] and that God would curse whites who married blacks.[8][3] These views were criticized by abolitionists of the day.[9][10] Though the church had an open membership policy for all races, relatively few black people who joined the church retained active membership.[11] Young had taught that the ban on blacks would one day be lifted when "all the other descendants of Adam have received the promises and enjoyed the blessings of the priesthood and the keys thereof".[12]

In the 1960s, Mormon attitudes about race were generally close to those of other Americans.[13][14] Accordingly, before the civil rights movement, the LDS Church's policy went largely unnoticed and unchallenged.[15][16] Beginning in the 1960s, however, the church was criticized by civil rights advocates and religious groups, and in 1969 several church leaders voted to rescind the policy, but the vote was not unanimous among the members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, so the policy stood. In 1978, the First Presidency and the Twelve, led by Spencer W. Kimball, declared they had received a revelation instructing them to reverse the racial restriction policy. The change seems to have been prompted at least in part by problems facing mixed race converts in Brazil. Today, the church opposes racism in any form and has no racial discrimination policy.[17]

In 1997, there were approximately 500,000 black members of the LDS Church, accounting for about five percent of the total membership; most black members live in Africa, Brazil, and the Caribbean.[18]

Before 1847

During the early years of the Latter Day Saint movement, black people were admitted to the church, and there was no record of a racial policy on denying priesthood, since at least two black men became priests, Elijah Abel and Walker Lewis.[21] When the Latter Day Saints migrated to Missouri, they encountered the pro-slavery sentiments of their neighbors. Joseph Smith upheld the laws regarding slaves and slaveholders, but remained abolitionist in his actions and doctrines.[4]

Racial discrimination policy under Brigham Young

After Smith's death in 1844, Brigham Young became president of the main body of the church and led the Mormon pioneers to what would become Utah Territory. Like many Americans at the time, Young (who was also the territorial governor) promoted discriminatory views about black people.[15] On January 16, 1852, Young made a pronouncement to the Utah Territorial Legislature, stating that "any man having one drop of the seed of [Cain] ... in him cannot hold the priesthood and if no other Prophet ever spake it before I will say it now in the name of Jesus Christ I know it is true and others know it."[22]

A similar statement by Young was recorded on February 13, 1849. The statement—which refers to the Curse of Cain—was given in response to a question asking about the African's chances for redemption. Young responded, "The Lord had cursed Cain's seed with blackness and prohibited them the Priesthood."[22]

William McCary

Some researchers have suggested that the actions of William McCary in Winter Quarters, Nebraska led to Brigham Young's decision to adopt the priesthood ban in the LDS Church. McCary was a half–African American convert who, after his baptism and ordination to the priesthood, began to claim to be a prophet and the possessor of other supernatural gifts.[23] He was excommunicated for apostasy in March 1847 and expelled from Winter Quarters.[24] After his excommunication, McCary began attracting Latter Day Saint followers and instituted plural marriage among his group, and he had himself sealed to several white wives.[23][24]

McCary's behavior angered many of the Latter Day Saints in Winter Quarters. Researchers have stated that his marriages to his white wives "played an important role in pushing the Mormon leadership into an anti-Black position"[23] and may have prompted Young to institute the priesthood and temple ban on black people.[23][24][25] A statement from Young to McCary in March 1847 suggested that race had nothing to do with priesthood eligibility,[26] but the earliest known statement about the priesthood restriction from any Mormon leader (including the implication that skin color might be relevant) was made by apostle Parley P. Pratt a month after McCary was expelled from Winter Quarters.[24] Speaking of McCary, Pratt stated that he "was a black man with the blood of Ham in him which lineage was cursed as regards the priesthood".[27]

Young's views

While Brigham Young opposed slavery, he was at least willing to tolerate it temporarily.[28] Young subscribed to what was a common American view at the time: that black people were naturally inferior.[29] Young attributed this to a divine curse placed on the lineage of Cain, and interpreted it to mean that Africans and their descendents could not be ordained to the priesthood. However, he rejected the teachings of contemporary Mormons including Orson Pratt, that Africans were cursed because they had been less valiant in a pre-mortal life.[30] Young also stated that curse would one day be lifted and that black people would be able to receive the priesthood post-mortally.[1]:43

As recorded in the Journal of Discourses, Young taught:

"You see some classes of the human family that are black, uncouth, uncomely, disagreeable and low in their habits, wild, and seemingly deprived of nearly all the blessings of the intelligence that is generally bestowed upon mankind . . . Cain slew his brother. Cain might have been killed, and that would have put a termination to that line of human beings. This was not to be, and the Lord put a mark upon him, which is the flat nose and black skin," (Journal of Discourses, vol. 7, p. 290).

"In our first settlement in Missouri, it was said by our enemies that we intended to tamper with the slaves, not that we had any idea of the kind, for such a thing never entered our minds. We knew that the children of Ham were to be the "servant of servants," and no power under heaven could hinder it, so long as the Lord would permit them to welter under the curse and those were known to be our religious views concerning them," (Journal of Discourses, vol. 2, p. 172).

"Shall I tell you the law of God in regard to the African race? If the white man who belongs to the chosen seed mixes his blood with the seed of Cain, the penalty, under the law of God, is death on the spot. This will always be so," (Journal of Discourses, vol. 10, p. 110).

Civil rights

Slavery

When church leaders asked for men from the members of Mississippi to help with the westward emigration, they sent four slaves, with John Brown given the task to "take charge of them". Two of the slaves died, and Green Flake later joined the company, making three slaves arriving in Utah.[32] More slaves arrived in later companies. By 1850, 100 blacks had arrived, the majority of which were slaves.[33] Other slaves were able to escape along the trek. One large contingent was able to escape from the Redds during the night in Kansas,[34] but six were not able to escape and continued on to Utah.[35] When William Dennis stopped in Tabor, Iowa, members of the Underground Railroad were able to help five slaves escape, and despite a man hunt, were able to make their way to Canada.[36][37]:39

After the pioneers arrived in Utah, they continued to buy and sell slaves as property. Many prominent members of the church were slave owners, including Abraham O. Smoot and Charles C. Rich.[38] Church members would use their slaves as tithing, both lending out their slaves to work for the church[39] as well as giving their slaves to the church.[32][37]:34 Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball used the slave labor that had been donated in tithing before granting their freedom.[32][37]:52

The church opposed slaves who wanted to escape their masters.[2][40] This was enforced by Utah laws. When Dan, a slave, tried to escape his master, William Camp, the courts upheld that Dan was Camp's property and could not escape. Dan was later sold to Thomas Williams for $800 and then to William Hooper.[32]

According to former slave Alexander Bankhead, the slaves were "far from being happy" and longed for their freedom. Many had received the same treatment as in the South. The slaves were incredibly joyful when the news reached that they were free, and many left Utah for other states, particularly California.[34][32]

In Mormon scripture

It was a commonly held belief in the South that the Bible permitted slavery. For instance, the Old Testament has stories of slavery, and gives rules and regulations on how to treat slaves, while the New Testament tells slaves not to revolt against their masters. However, the Doctrine and Covenants condemns slavery, teaching "it is not right that any man should be in bondage one to another." (D&C 101:79) The Book of Mormon heralds righteous kings who did not allow slavery, (Mosiah 29:40) and righteous men who fought against slavery (Alma 48:11). The Book of Mormon also describes an ideal society that lived around AD 34–200, in which it teaches the people "had all things common among them; therefore there were not rich and poor, bond and free, but they were all made free, and partakers of the heavenly gift" (4 Nephi 4:3), and says that all people are children of God and "he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female" (2 Nephi 26:33). The Book of Moses describes a similar society, in which "they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them" (Moses 7:18). Mormons believed they too, were commanded by the Lord to "be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine" (D&C 38:27). For a short time, Mormons lived in a society with no divisions under the United Order.

Statements from church leaders

Beginning in 1842, after he had moved to free-state Illinois, Smith made known his increasingly strong anti-slavery position. In 1842, he began studying some abolitionist literature, and stated, "It makes my blood boil within me to reflect upon the injustice, cruelty, and oppression of the rulers of the people. When will these things cease to be, and the Constitution and the laws again bear rule?"[41] In 1844, Smith wrote his views as a candidate for president of the United States. The anti-slavery plank of his platform called for a gradual end to slavery by the year 1850. His plan called for the government to buy the freedom of slaves using money from the sale of public lands.[4]

During the Missouri period, a number of slave owners had converted to Mormonism. There was a question on the church's stance on slavery during the migration to Utah. In 1851, apostle Orson Hyde said:

We feel it to be our duty to define our position in relation to the subject of slavery. There are several in the Valley of the Salt Lake from the Southern States, who have their slaves with them. There is no law in Utah to authorize slavery, neither any to prohibit it. If the slave is disposed to leave his master, no power exists there, either legal or moral, that will prevent him. But if the slave chooses to remain with his master, none are allowed to interfere between the master and the slave. All the slaves that are there appear to be perfectly contented and satisfied.When a man in the Southern states embraces our faith, the Church says to him, if your slaves wish to remain with you, and to go with you, put them not away; but if they choose to leave you, or are not satisfied to remain with you, it is for you to sell them, or let them go free, as your own conscience may direct you. The Church, on this point, assumes not the responsibility to direct. The laws of the land recognize slavery, we do not wish to oppose the laws of the country. If there is sin in selling a slave, let the individual who sells him bear that sin, and not the Church.[42]

Brigham Young believed that slavery was "of Divine institution, and not to be abolished until the curse pronounced on Ham shall have been removed from his descendants."[2] In the year following the Emancipation Proclamation, Young gave several discourses on slavery. He characterized himself as neither an abolitionist nor a pro-slavery man.[3] He taught that blacks should have remained slaves but be treated kindly. Like many Christians of the day, he believed in the Curse of Cain and Curse of Ham and taught that God had decreed that blacks should remain servants of servants[43] and that they were incapable of rising above the position of a servant. It was therefore up to slave owner to treat them kindly.[44] Young said, "If the Government of the United States, in Congress assembled, had the right to pass an anti-polygamy bill, they had also the right to pass a law that slaves should not be abused as they have been; they had also a right to make a law that negroes should be used like human beings, and not worse than dumb brutes. For their abuse of that race, the whites will be cursed, unless they repent."[3]

He criticized the Southerners for their mistreatment of their slaves and accused the Northerners of almost worshipping the slaves in their attempts to free them. He opposed the American Civil War, calling it useless and that the "cause of human improvement is not in the least advanced" by trying to free the slaves.[43] He prophesied that the attempts to free the slave would eventually fail:

Will the present struggle free the slave? No; but they are now wasting away the black race by thousands. Many of the blacks are treated worse than we treat our dumb brutes; and men will be called to judgment for the way they have treated the negro, and they will receive the condemnation of a guilty conscience, by the just Judge whose attributes are justice and truth. Treat the slaves kindly and let them live, for Ham must be the servant of servants until the curse is removed. Can you destroy the decrees of the Almighty? You cannot. Yet our Christian brethren think that they are going to overthrow the sentence of the Almighty upon the seed of Ham. They cannot do that, though they may kill them by thousands and tens of thousands.[43]

In Utah Territory

The Great Compromise of 1850 allowed California into the Union as a free state while permitting Utah and New Mexico territories the option of deciding the issue by popular sovereignty. In 1852, the Utah Territorial Legislature took up the issue of legalizing slavery. At that time, Brigham Young was governor, and the Utah Territorial Legislature was dominated by church leaders.[45] On January 23, 1852, Brigham Young addressed the joint session of the legislature advocating slavery. He made the matter religious, by declaring "Inasmuch as we believe in the Bible, inasmuch as we believe in the ordinances of God, in the Priesthood and order and decrees of God, we must believe in slavery." He argued that the blacks had the Curse of Ham placed on them which made them servants of servants and that he was not authorized to remove it. He argued that blacks needed to serve masters because they are not capable of ruling themselves, and that when treated right, blacks were much better off as slaves than if they were free.[46] Following the speech, the Utah Legislature passed an Act in Relation to Service, which officially sanctioned slavery in Utah Territory.[33] The Utah slavery law stipulated that slaves would be freed if their masters had sexual relations with them; attempted to take them from the territory against their will; or neglected to feed, clothe, or provide shelter to them. In addition, the law stipulated that slaves must receive schooling.

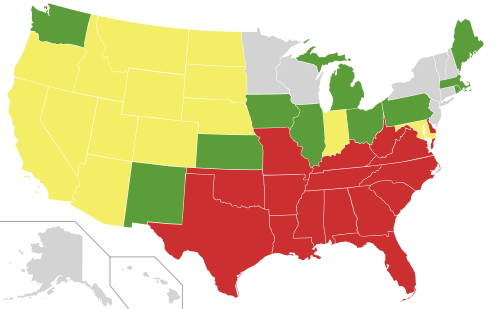

Utah was the only western state or territory that had slaves in 1850,[47] but slavery was never important economically in Utah, and there were fewer than 100 slaves in the territory.[15] In 1860, the census showed that 29 of the 59 black people in Utah Territory were slaves. When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, Utah sided with the Union, and slavery ended in 1862 when the United States Congress abolished slavery in the Utah Territory.

.jpg)

In San Bernardino

In 1851, a company of 437 Mormons under direction of Elders Amasa M. Lyman and Charles C. Rich of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles settled at what is now San Bernardino. This first company took 26 slaves,[48] and more slaves were brought over as San Bernardino continued to grow.[49] Since California was a free state, the slaves should have been freed when they entered. However, slavery was openly tolerated in San Bernardino.[50] Many wanted to be free,[51] but were still under the control of their masters and ignorant of the laws and their rights. Judge Benjamin Hayes freed 14 slaves who had belonged to Robert Smith.[52] Other slaves were freed by their masters.[48]

Criticism

The Mormon position of slavery was criticized by abolitionists of the day. While considering appropriations for Utah Territory, Representative Justin Smith Morrill criticized the Mormon church for its laws on slavery. He said that under the Mormon patriarchy, slavery took a new shape. He criticized the use of the term servants instead of slaves and the requirement for Mormon masters to "correct and punish" their "servants". He expressed concern that Mormons might be trying to increase the number of slaves in the state.[10] Horace Greeley also criticized the Mormon position on slavery and general apathy towards the welfare of black people.[9]

Interracial marriages and interacial sexual relations

In February 6, 1835, an assistant president of the church, W. W. Phelps, wrote a letter theorizing that Ham's wife was a descendant of Cain and that Ham himself was cursed for "marrying a black wife".[54][55]:1827[56]:237[57][58][59]

Joseph Smith opposed interracial marriages.[60] He taught "Had I anything to do with the negro, I would confine them by strict law to their own species."[61] In Nauvoo, it was against the law for black men to marry whites, and Joseph Smith fined two black men for violating his probation of intermarriage between blacks and whites.[62]

During a sermon criticizing the federal government, church president Brigham Young said "If the white man who belongs to the chosen seed mixes his blood with the seed of Cain, the penalty, under the law of God, is death on the spot. This will always be so."[3] It has been argued that the type of sexual relations that Young envisioned in this statement were those between a slave owner and slave.[63]

During the 19th century the Utah legislature passed Act in Relation to Service which carried penalties for whites who had sexual relations with blacks. The day after it passed, he explained that that if someone mixes their seed with the seed of Cain, that both they and their children will have the Curse of Cain. He then prophesied that if the Church were to ever say that it was okay to intermarry with blacks, that the Church would go on to destruction and the priesthood would be taken away.[8] The seed of Cain generally referred to those with dark skin of African descent.

In the early-20th century, church apostle Brigham Young, Jr. warned members of the church living in Arizona "that the blood of Cain was more predominant in these Mexicans than that of Israel." For this reason, he "condemned the mixing" of Mormons with "outsiders."[64]

Church apostle Mark E. Petersen said in 1954: "I think I have read enough to give you an idea of what the Negro is after. He is not just seeking the opportunity of sitting down in a cafe where white people eat. He isn't just trying to ride on the same streetcar or the same Pullman car with white people. It isn't that he just desires to go to the same theater as the white people. From this, and other interviews I have read, it appears that the Negro seeks absorption with the white race. He will not be satisfied until he achieves it by intermarriage. That is his objective and we must face it."[65]

In a 1965 address to BYU students, apostle Spencer W. Kimball told BYU students: "Now, the brethren feel that it is not the wisest thing to cross racial lines in dating and marrying. There is no condemnation. We have had some of our fine young people who have crossed the lines. We hope they will be very happy, but experience of the brethren through a hundred years has proved to us that marriage is a very difficult thing under any circumstances and the difficulty increases in interrace marriages."[66] A church lesson manual for adolescent boys, published in 1995, contains a 1976 quote from Spencer W. Kimball that recommended the practice of marrying others of similar racial, economic, social, educational, and religious backgrounds.[67][68]

The official newspaper of the LDS Church,[69] the Church News, printed an article entitled "Interracial marriage discouraged". This article was printed on June 17, 1978, in the same issue that announced the policy reversal for blacks and the priesthood.

There was no written church policy on interracial marriages, which had been permitted since before the 1978 Revelation on the Priesthood.[66] In 1978, church spokesman Don LeFevre said "So there is no ban on interracial marriage. If a black partner contemplating marriage is worthy of going to the Temple, nobody's going to stop him .... if he's ready to go to the Temple, obviously he may go with the blessings of the church."[70]

Speaking on behalf of the church, Robert Millet wrote in 2003: "[T]he Church Handbook of Instructions ... is the guide for all Church leaders on doctrine and practice. There is, in fact, no mention whatsoever in this handbook concerning interracial marriages. In addition, having served as a Church leader for almost 30 years, I can also certify that I have never received official verbal instructions condemning marriages between black and white members."[71]

The Church continues to advise against interracial marriage.[60] In 1995, the Church published the Aaronic Priesthood Manual 3, which quotes Kimball's advice to "marry those who are of the same racial background". This is the official manual currently used to teach 12 and 13 year old boys on Sunday.[72] In 2003, the Church published the Eternal Marriage Student Manual, which uses the same quote.[73]

Black suffrage

As in other places in Illinois, only free white males could vote in Nauvoo.[62]

When Utah territory was created, suffrage was only granted to free white males.[74] At that time, only a few states had allowed black suffrage. Brigham Young explained that this was connected to the priesthood ban. He argued that "If Africans cannot bear rule in the Church of God, what business have they to bear rule in the State and government affairs of this Territory or any other?" He said they had no right and he would not consent that the children of Cain rule over him. He argued that the attempt to grant black suffrage was part of a larger attempt to make black equal to whites, which would bring a curse.[1]:46-48

On January 10, 1867, Congress passed the Territorial Suffrage Act, which prohibited denying suffrage based on race or previous condition of servitude, which nullified Utah's ban on black suffrage.[75]

Other racial discrimination

Like most Americans between the 19th and mid-20th centuries, some Mormons held racist views, and exclusion from priesthood was not the only discrimination practiced toward black people. With Joseph Smith as the mayor of Nauvoo, blacks were prohibited from holding office or joining the Nauvoo Legion.[62] Brigham Young taught that equality efforts were misguided, claiming that those who fought for equality among blacks were trying to elevate them "to an equality with those whom Nature and Nature's God has indicated to be their masters, their superiors", but that instead they should "observe the law of natural affection for our kind."[76] After slavery was made illegal in Utah, Young supported legislation that prohibited blacks from voting, holding public office, belonging to the territorial militia, and intermarrying with whites.[33]:804 In the late 1800s, blacks living in Cache Valley were forcibly relocated to Ogden and Salt Lake City. In the 1950s, the San Francisco mission office took legal action to prevent black families from moving into the church neighborhood.[77] In 1965, a black man living in Salt Lake City, Daily Oliver, described how—as a boy—he was excluded from an LDS-led boy scout troop because they did not want blacks in their building.[78] LDS Church apostle Mark E. Petersen describes a black family that tried to join the LDS Church: "[some white church members] went to the Branch President, and said that either the [black] family must leave, or they would all leave. The Branch President ruled that [the black family] could not come to church meetings. It broke their hearts."[79] Until the 1970s hospitals with connections to the LDS Church, including LDS Hospital, Primary Children's and Cottonwood Hospitals in Salt Lake City, McKay-Dee Hospital in Ogden, and Utah Valley Hospital in Provo, kept separate the blood donated by blacks and whites, and even after the church's volte face in 1978 patients who expressed concern about receiving blood from black donors were given reassurance from hospital authorities that this would not happen.[80]

Civil rights movement

In 1958, apostle Joseph Fielding Smith published Answers to Gospel Questions, which stated that "no church or other organization is more insistent than The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, that the negroes should receive all the rights and privileges that can possibly be given to any other in the true sense of equality as declared in the Declaration of Independence." He went on to say that negroes should not be barred from any type of employment or education, and should be free "to make their lives as happy as it is possible without interference from white men, labor unions or from any other source."[81] In the 1963 church General Conference, apostle Hugh B. Brown stated: "it is a moral evil for any person or group of persons to deny any human being the rights to gainful employment, to full educational opportunity, and to every privilege of citizenship". He continued: "We call upon all men everywhere, both within and outside the church, to commit themselves to the establishment of full civil equality for all of God's children. Anything less than this defeats our high ideal of the brotherhood of man."[81]

In the 1960s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) attempted to convince LDS Church leaders to support civil rights legislation and to reverse its practices in relation to African American priesthood holding and temple attendance during the Civil Rights era. In early 1963, NAACP leadership attempted to arrange meetings with church leadership but were rebuffed in their efforts.[77] Later, before the October 1963 General Conference, N. Eldon Tanner and Hugh B. Brown, the two counselors to David O. McKay in the First Presidency, met with the head of the Utah NAACP. During the ensuring general conference, Brown issued a statement in support of civil rights legislation worded in a way that made it sound as if it reflected the views of the entire First Presidency.[82]

In 1965, the church leadership met with the national NAACP, and agreed to publish an editorial in church-owned newspaper the Deseret News, which would support civil rights legislation pending in the Utah legislature. The church failed to follow-through on the commitment, and Tanner explained, "We have decided to remain silent".[77]

In March 1965, the NAACP led an anti-discrimination march in Salt Lake City, protesting church policies.[77] In 1966, the NAACP issued a statement criticizing the church, saying the church "has maintained a rigid and continuous segregation stand" and that "the church has made "no effort to conteract the widespread discriminatory practices in education, in housing, in employment, and other areas of life"[83] However, in a study covering 1972 to 1996, church membership has been shown to have lower rates of approval of segregation than the national norm, as well as a faster decline in approval over the periods covered, both with statistical significance.[84]:p.94–97

During the 1960s and 1970s, Mormons in the West were close to the national averages in racial attitudes.[15] In 1966, Armand Mauss surveyed Mormons on racial attitudes and discriminatory practices. He found that "Mormons resembled the rather 'moderate' denominations (such as Presbyterian, Congregational, Episcopalian), rather than the 'fundamentalists' or the sects."[85] Negative racial attitudes within Mormonism varied inversely with education, occupation, community size of origin, and youth, reflecting the national trend. Urban Mormons with a more orthodox view of Mormonism tended to be more tolerant.[85]

African-American athletes protested against LDS Church policies by boycotting several sporting events with Brigham Young University. In 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King, black members of the UTEP track team approached their coach and expressed their desire not to compete against BYU in an upcoming meet. When the coach disregarded the athletes' complaint, the athletes boycotted the meet.[86] In 1969, 14 members of the University of Wyoming football team were removed from the team for planning to protest the policies of the LDS church.[86] In November 1969, Stanford University President Kenneth Pitzer suspended athletic relations with BYU.[87]

Since the early part of the 20th century, each ward of the LDS Church in the United States has organized its own Boy Scouting troop. Some LDS Church-sponsored troops permitted black youths to join, but a church policy required that the troop leader to be the deacons quorum president, which had the result of excluding black children from that role. The NAACP filed a federal lawsuit in 1974 challenging this practice, and soon thereafter the LDS Church reversed its policy.[88][89]

In the early 1970s, apostle Spencer W. Kimball began preaching against racism. In 1972, he said: "Intolerance by Church members is despicable. A special problem exists with respect to black people because they may not now receive the priesthood. Some members of the Church would justify their own un-Christian discrimination against black people because of that rule with respect to the priesthood, but while this restriction has been imposed by the Lord, it is not for us to add burdens upon the shoulders of our black brethren. They who have received Christ in faith through authoritative baptism are heirs to the celestial kingdom along with men of all other races. And those who remain faithful to the end may expect that God may finally grant them all blessings they have merited through their righteousness. Such matters are in the Lord's hands. It is for us to extend our love to all."[90]

There were some LDS Church members who protested against the church's discriminatory practices. Two members, Douglas A. Wallace and Byron Merchant, were excommunicated by the LDS Church in 1976 and 1977 respectively, after criticizing the church's practices.[91][92][93][94] Church member Grant Syphers objected to the church's racial policies and, as a consequence, his stake president refused to give Syphers a temple recommend. The president said, "Anyone who could not accept the Church's stand on Negroes ... could not go to the temple".[95]

Racial restriction policy

Under the racial restrictions that lasted from the presidency of Brigham Young until 1978, persons with any black African ancestry could not hold the priesthood in the LDS Church and could not participate in most temple ordinances, including the endowment and celestial marriage. Black people were permitted to be members of the church, and to participate in some temple ordinances, such as baptism for the dead.[96]

The racial restriction policy was applied to black Africans, persons of black African descent, and any one with mixed race that included any black African ancestry. The policy was not applied to Native Americans, Hispanics, Melanesians, or Polynesians.

Priesthood

Brigham Young taught that black men would not receive the Mormon priesthood until "all the other descendants of Adam have received the promises and enjoyed the blessings of the priesthood and the keys thereof".[12]

The priesthood restriction was particularly limiting, because the LDS Church has a lay priesthood and all worthy male members may receive the priesthood. Young men are generally admitted to the Aaronic priesthood at age 12, and it is a significant rite of passage. Virtually all white adult male members of the church held the priesthood. Holders of the priesthood officiate at church meetings, perform blessings of healing, and manage church affairs. Excluding black people from the priesthood meant that they could not hold significant church leadership roles or participate in certain spiritual events.

Don Harwell, a black LDS Church member, said, "I remember being in a Sacrament meeting, pre-1978, and the sacrament was being passed and there was special care taken by this person that not only did I not officiate, but I didn't touch the sacrament tray. They made sure that I could take the sacrament, but that I did not touch the tray and it was passed around me. That was awfully hard, considering that often those who were officiating were young men in their early teens, and they had that priesthood. I valued that priesthood, but it wasn't available."[97]

Temple ordinances

Between 1844 and 1977, most black people were not permitted to participate in ordinances performed in the LDS Church temples, such as the endowment ritual, celestial marriages, and family sealings. These ordinances are considered essential to enter the highest degree of heaven, so this meant that they could not enjoy the full privileges enjoyed by other Latter-day Saints during the restriction.

Latter-day Saints believe that marriages that are sealed in a celestial marriage would bind the family together forever, whereas those that are not sealed were terminated upon death. Church president David O. McKay taught that black people "need not worry, as those who receive the testimony of the Restored Gospel may have their family ties protected and other blessings made secure, for in the justice of the Lord they will possess all the blessings to which they are entitled in the eternal plan of Salvation and Exaltation."[98]

Brigham Young taught that "When the ordinances are carried out in the temples that will be erected, [children] will be sealed to their [parents], and those who have slept, clear up to Father Adam. This will have to be done ... until we shall form a perfect chain from Father Adam down to the closing up scene."[99] Once black people were allowed to participate in temple ordinances, they could also perform the ordinances for their ancestors.

Entrance to the highest heaven

A celestial marriage is considered unnecessary to gain access into the celestial kingdom, but it is required to obtain a fullness of glory or exaltation within the celestial kingdom.[100] The Doctrine and Covenants states, "In the celestial glory there are three heavens or degrees; And in order to obtain the highest, a man must enter into this order of the priesthood [meaning the new and everlasting covenant of marriage]; And if he does not, he cannot obtain it."(D&C 131:1-3) The righteous who do not have a celestial marriage would still make it into heaven, and live eternally with God, but they would be "appointed angels in heaven, which angels are ministering servants."(D&C 132:16)

Some interpreted this to mean black people would be treated as unmarried whites, being confined to only ever live in God's presence as a ministering servant. In 1954, apostle Mark E. Petersen told Brigham Young University students: "If that Negro is faithful all his days, he can and will enter the celestial kingdom. He will go there as a servant, but he will get a celestial resurrection."[101] Apostle George F. Richards, in a talk at a General Conference, similarly taught: "The Negro is an unfortunate man. He has been given a black skin. But that is as nothing compared with that greater handicap that he is not permitted to receive the Priesthood and the ordinances of the temple, necessary to prepare men and women to enter into and enjoy a fullness of glory in the celestial kingdom."[102]

Several leaders, including Joseph Smith,[103] Brigham Young,[104] Wilford Woodruff,[105] George Albert Smith,[106] David O. McKay,[107] Joseph Fielding Smith,[108] and Harold B. Lee[109] taught that black people would eventually be able to receive a fullness of glory in the celestial kingdom.

When the priesthood ban was discussed in 1978, apostle Bruce R. McConkie argued for its change using Mormon scriptures and the Articles of Faith. The Third Article states that "all mankind may be saved, by obedience to the laws and ordinances of the Gospel" (Articles of Faith 1:3). From the Book of Mormon he quoted, "And even unto the great and last day, when all people, and all kindreds, and all nations and tongues shall stand before God, to be judged of their works, whether they be good or whether they be evil—If they be good, to the resurrection of everlasting life; and if they be evil, to the resurrection of damnation" (3 Nephi 26:4-5)' The Book of Abraham in the Pearl of Great Price states that through Abraham's seed "shall all the families of the earth be blessed, even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal" (Abraham 2:11), According to McConkie's son, Joseph Fielding McConkie, the highlighting of these scriptures played a role in changing the policy.[110]

Speculation on rationale for racial restrictions

Author David Persuitte has pointed out that it was commonplace in the 19th century for theologians, including Joseph Smith, to believe that the curse of Cain was exhibited by a black skin, and that this genetic trait had descended through Noah's son Ham, who was understood to have married a black wife.[56] Mormon historian Claudia Bushman also identifies doctrinal explanations for the exclusion of blacks, with one justification originating in papyrus rolls translated by Joseph Smith as the Book of Abraham, a passage of which links ancient Egyptian government to the cursed Ham through Pharaoh, Ham's grandson, who was "of that lineage by which he could not have the right of Priesthood".[111]:p.93

Another speculated reason for racial restriction has been called by Colin Kidd "Mormon karma", where skin color is perceived as evidence of righteousness (or its lack thereof) in a pre-mortal existence.[112]:p.236 The doctrine of premortal existence is described in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism in this way: "to Latter-day Saints premortal life is characterized by individuality, agency, intelligence, and opportunity for eternal progression. It is a central doctrine of the theology of the Church and provides understanding to the age-old question 'Whence cometh man?'"[113] This idea is based on the opinions of several prominent church leaders, including apostle Joseph Fielding Smith, who held the view that the premortal life had been a kind of testing ground for the assignment of God's spiritual children to favored or disfavored mortal lineages.[112]:pp.236–237 Bushman has also noted Smith's long-time teachings that in a premortal war in heaven, blacks were considered to have been those spirits who did not fight as valiantly against Satan and who, as a result, received a lesser earthly stature, with such restrictions as being disqualified from holding the priesthood.[111]:p.93 According to religious historian Craig Prentiss,[114] the appeal to premortal existence was confirmed as doctrine through statements of the LDS First Presidency in 1949[115] and 1969.[116]

Church leadership officially cited various reasons[117] for the doctrinal ban, but later leaders have since repudiated them.[17][118][119][120][121][122] In 2014, the LDS Church issued an official statement about past racist practices and theories: "Today, the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else. Church leaders today unequivocally condemn all racism, past and present, in any form."[123]

1880–1950

Under John Taylor's presidency (1880–87), there was confusion in the church regarding the origin of the racial policy. Elijah Abel was living proof that an African American was ordained to the priesthood in the days of Joseph Smith. His son, Enoch Abel, had also received the priesthood.[124] Apostle Joseph F. Smith argued that Abel's priesthood had been declared null and void by Joseph Smith, though this seems to conflict with Joseph F. Smith's teachings that the priesthood could not be removed from any man without removing that man from the church.[125] Zebedee Coltrin and Abraham O. Smoot provided conflicting testimony that Joseph Smith stated that Abel could not hold the priesthood, though the veracity of their testimony is doubted.[126]:38[55]:6 From this point on, many statements on the priesthood restriction were attributed to Joseph Smith; all such statements had actually been made by Brigham Young.[125]

Several black men received the priesthood after the racial restriction policy was put in place, including Elijah Abel's son Enoch Abel, who was ordained an elder on November 10, 1900. Enoch's son and Elijah Abel's grandson—who was also named Elijah Abel—received the Aaronic priesthood and was ordained to the office of priest on July 5, 1934. The younger Elijah Abel also received the Melchizedek priesthood and was ordained to the office of elder on September 29, 1935.[127]:p.30 One commentator has pointed out that these incidents illustrate the "ambiguities, contradictions, and paradoxes" of the issue during the twentieth century.[127]

<span id="The "Negro Question" Declaration"> In 1949, the First Presidency, under the direction of George Albert Smith, made a declaration which included the statement that the priesthood restriction was divinely commanded and not a matter of church policy.[128] It stated:[129]

The attitude of the Church with reference to the Negroes remains as it has always stood. It is not a matter of the declaration of a policy but of direct commandment from the Lord, on which is founded the doctrine of the Church from the days of its organization, to the effect that Negroes may become members of the Church but that they are not entitled to the Priesthood at the present time. The prophets of the Lord have made several statements as to the operation of the principle. President Brigham Young said: "Why are so many of the inhabitants of the earth cursed with a skin of blackness? It comes in consequence of their fathers rejecting the power of the holy priesthood, and the law of God. They will go down to death. And when all the rest of the children have received their blessings in the holy priesthood, then that curse will be removed from the seed of Cain, and they will then come up and possess the priesthood, and receive all the blessings which we now are entitled to."

President Wilford Woodruff made the following statement: "The day will come when all that race will be redeemed and possess all the blessings which we now have."

The position of the Church regarding the Negro may be understood when another doctrine of the Church is kept in mind, namely, that the conduct of spirits in the premortal existence has some determining effect upon the conditions and circumstances under which these spirits take on mortality and that while the details of this principle have not been made known, the mortality is a privilege that is given to those who maintain their first estate; and that the worth of the privilege is so great that spirits are willing to come to earth and take on bodies no matter what the handicap may be as to the kind of bodies they are to secure; and that among the handicaps, failure of the right to enjoy in mortality the blessings of the priesthood is a handicap which spirits are willing to assume in order that they might come to earth. Under this principle there is no injustice whatsoever involved in this deprivation as to the holding of the priesthood by the Negroes.

1951–77

In 1954, church president David O. McKay taught: "There is not now, and there never has been a doctrine in this church that the negroes are under a divine curse. There is no doctrine in the church of any kind pertaining to the negro. We believe that we have a scriptural precedent for withholding the priesthood from the negro. It is a practice, not a doctrine, and the practice someday will be changed. And that's all there is to it."[122]

Apostle Mark E. Petersen addressed the issue of race and priesthood in his address to a 1954 Convention of Teachers of Religion at the College Level at Brigham Young University. He said:

The reason that one would lose his blessings by marrying a negro is due to the restriction placed upon them. "No person having the least particle of negro blood can hold the priesthood" (Brigham Young). It does not matter if they are one-sixth negro or one-hundred and sixth, the curse of no Priesthood is the same. If an individual who is entitled to the priesthood marries a negro, the Lord has decreed that only spirits who are not eligible for the priesthood will come to that marriage as children. To intermarry with a negro is to forfeit a "nation of priesthood holders".[130]

Petersen held that male descendants of a mixed-marriage could not become a Mormon priesthood holder, even if they had a lone ancestor with African blood dating back many generations.[131]

In 1969, church apostle Harold B. Lee blocked the LDS Church from rescinding the racial restriction policy.[132] Church leaders voted to rescind the policy at a meeting in 1969. Lee was absent from the meeting due to travels. When Lee returned he called for a re-vote, arguing that the policy could not be changed without a revelation.[132]

In her book, Contemporary Mormonism, Claudia Bushman has described the pain caused by the racial policy of the church, both to black worshipers, who sometimes found themselves segregated and ostracized, and to white members who were embarrassed by the exclusionary practices and who occasionally apostatized over the issue.[111]:pp.94–95

In 1971, three African-American Mormon men petitioned then–church president Joseph Fielding Smith to consider ways to keep black families involved in the church and also re-activate the descendants of black pioneers.[133] As a result, Smith directed three apostles to meet with the men on a weekly basis until, on October 19, 1971, an organization called the Genesis Group was established as an auxiliary unit of LDS Church to meet the needs of black Mormons.[134] The first president of the Genesis Group was Ruffin Bridgeforth, who also became the first black Latter-day Saint to be ordained a high priest after the priesthood ban was lifted later in the decade.[135]

Harold B. Lee, president of the church, stated in 1972: "For those who don't believe in modern revelation there is no adequate explanation. Those who do understand revelation stand by and wait until the Lord speaks .... It's only a matter of time before the black achieves full status in the Church. We must believe in the justice of God. The black will achieve full status, we're just waiting for that time."[136]

Racial policy ends in 1978

In the 1970s, LDS Church president Spencer W. Kimball took general conference on the road, holding area and regional conferences all over the world. He also announced many new temples to be built both in the United States and abroad, including one temple in São Paulo, Brazil. The problem of determining priesthood eligibility in Brazil was thought to be nearly impossible due to the mixing of the races in that country. When the temple was announced, church leaders realized the difficulty of restricting persons with African descent from attending the temple in Brazil.[137]

On June 8, 1978, the First Presidency released to the press an official declaration, now a part of Doctrine and Covenants, which contained the following statement:

He has heard our prayers, and by revelation has confirmed that the long-promised day has come when every faithful, worthy man in the church may receive the Holy Priesthood, with power to exercise its divine authority, and enjoy with his loved ones every blessing that follows there from, including the blessings of the temple. Accordingly, all worthy male members of the church may be ordained to the priesthood without regard for race or color. Priesthood leaders are instructed to follow the policy of carefully interviewing all candidates for ordination to either the Aaronic or the Melchizedek Priesthood to insure that they meet the established standards for worthiness.[138]

According to first-person accounts, after much discussion among the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles on this matter, they engaged the Lord in prayer. According to the writing of one of those present, "It was during this prayer that the revelation came. The Spirit of the Lord rested upon us all; we felt something akin to what happened on the day of Pentecost and at the Kirtland Temple. From the midst of eternity, the voice of God, conveyed by the power of the Spirit, spoke to his prophet. The message was that the time had now come to offer the fullness of the everlasting gospel, including celestial marriage, and the priesthood, and the blessings of the temple, to all men, without reference to race or color, solely on the basis of personal worthiness. And we all heard the same voice, received the same message, and became personal witnesses that the word received was the mind and will and voice of the Lord."[139] Immediately after the receipt of this new revelation, an official announcement of the revelation was prepared, and sent out to all of the various leaders of the Church. It was then read to, approved by and accepted as the word and will of the Lord, by a General Conference of the Church in October 1978. Succeeding editions of the Doctrine and Covenants were printed with this announcement canonized and entitled "Official Declaration 2".

Apostle Gordon B. Hinckley (a participant in the meetings to reverse the ban), in a churchwide fireside said, "Not one of us who was present on that occasion was ever quite the same after that. Nor has the Church been quite the same. All of us knew that the time had come for a change and that the decision had come from the heavens. The answer was clear. There was perfect unity among us in our experience and in our understanding."[140]

Later in 1978, McConkie said:[141]

There are statements in our literature by the early brethren which we have interpreted to mean that the Negroes would not receive the priesthood in mortality. I have said the same things, and people write me letters and say, "You said such and such, and how is it now that we do such and such?" And all I can say to that is that it is time disbelieving people repented and got in line and believed in a living, modern prophet. Forget everything that I have said, or what President Brigham Young or President George Q. Cannon or whomsoever has said in days past that is contrary to the present revelation. We spoke with a limited understanding and without the light and knowledge that now has come into the world.... We get our truth and our light line upon line and precept upon precept. We have now had added a new flood of intelligence and light on this particular subject, and it erases all the darkness and all the views and all the thoughts of the past. They don't matter any more .... It doesn't make a particle of difference what anybody ever said about the Negro matter before the first day of June of this year.

On June 11, 1978, three days after the announcement of the revelation, Joseph Freeman, a member of the church since 1973, became the first black man to be ordained to the office of elder in the Melchizedek priesthood since the ban was lifted, while several others were ordained into the Aaronic priesthood that same day.[142]

Critics of the LDS Church state that the church's 1978 reversal of the racial restriction policy was not divinely inspired as the church claimed, but simply a matter of political convenience,[143] as the reversal of policy occurred as the church began to expand outside the United States into countries such as Brazil that have ethnically mixed populations, and that the policy reversal was announced just a few months before the church opened its new temple in São Paulo, Brazil.[144]

1978 to present

Since the Revelation on the Priesthood in 1978, the church has made no distinctions in policy for black people, but it remains an issue for many black members of the church. Alvin Jackson, a black bishop in the LDS Church, puts his focus on "moving forward rather than looking back."[145] In an interview with Mormon Century, Jason Smith expresses his viewpoint that the membership of the church was not ready for black people to have the priesthood in the early years of the church, because of prejudice and slavery. He draws analogies to the Bible where only the Israelites have the gospel.[146]

Today, the church actively opposes racism among its membership. It is currently working to reach out to black people, and has several predominantly black wards inside the United States.[147] It teaches that all are invited to come unto Christ and it speaks against those who harbor ill feelings towards another race. In 2006, church president Gordon B. Hinckley stated:

I remind you that no man who makes disparaging remarks concerning those of another race can consider himself a true disciple of Christ. Nor can he consider himself to be in harmony with the teachings of the Church of Christ. Let us all recognize that each of us is a son or daughter of our Father in Heaven, who loves all of His children.[17]

In the July 1992 edition of the New Era, the church published a MormonAd promoting racial equality in the church. The photo contained several youth of a variety of ethic backgrounds with the words "Family Photo" in large print. Underneath the picture are the words "God created the races—but not racism. We are all children of the same Father. Violence and hatred have no place in His family. (See Acts 10:34.)"[148]

In December 2013, the LDS Church published an essay on lds.org in an effort to explain the history of the church's stance on race and the priesthood as well as disavowing some of the theories advanced stating that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor.[149]

Instances of discrimination after 1978 revelation

LDS historian Wayne J. Embry interviewed several black LDS Church members in 1987 and reported "All of the interviewees reported incidents of aloofness on the part of white members, a reluctance or a refusal to shake hands with them or sit by them, and racist comments made to them." Embry further reported that one black church member "was amazingly persistent in attending Mormon services for three years when, by her report, no one would speak to her." Embry reports that "she [the same black church member] had to write directly to the president of the LDS Church to find out how to be baptized" because none of her fellow church members would tell her.[150]:p.75–77

Black LDS Church member Darron Smith wrote in 2003: "Even though the priesthood ban was repealed in 1978, the discourse that constructs what blackness means is still very much intact today. Under the direction of President Spencer W. Kimball, the First Presidency and the Twelve removed the policy that denied black people the priesthood but did very little to disrupt the multiple discourses that had fostered the policy in the first place. Hence there are Church members today who continue to summon and teach at every level of Church education the racial discourse that black people are descendants of Cain, that they merited lesser earthly privilege because they were "fence-sitters" in the War in Heaven, and that, science and climatic factors aside, there is a link between skin color and righteousness".[151]

In 2007, journalist and church member, Peggy Fletcher Stack, wrote "Today, many black Mormons report subtle differences in the way they are treated, as if they are not full members but a separate group. A few even have been called 'the n-word' at church and in the hallowed halls of the temple. They look in vain at photos of Mormon general authorities, hoping to see their own faces reflected there.[152]

White church member Eugene England, a professor at Brigham Young University, wrote in 1998:

This is a good time to remind ourselves that most Mormons are still in denial about the ban, unwilling to talk in Church settings about it, and that some Mormons still believe that Blacks were cursed by descent from Cain through Ham. Even more believe that Blacks, as well as other non-white people, come color-coded into the world, their lineage and even their class a direct indication of failures in a previous life.... I check occasionally in classes at BYU and find that still, twenty years after the revelation, a majority of bright, well-educated Mormon students say they believe that Blacks are descendants of Cain and Ham and thereby cursed and that skin color is an indication of righteousness in the pre-mortal life. They tell me these ideas came from their parents or Seminary and Sunday School teachers, and they have never questioned them. They seem largely untroubled by the implicit contradiction to basic gospel teachings.[153]

In an interview for the PBS documentary The Mormons, Jeffrey R. Holland, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, specifically denounced the perpetuation of folklore suggesting that race was in any way an indication of how faithful a person had been in the pre-mortal existence.[154]

Church asked to repudiate past declarations

In 1995, black church member A. David Jackson asked church leaders to issue a declaration repudiating past doctrines that denied various privileges to black people. In particular, Jackson asked the church to disavow the 1949 "Negro Question" declaration from the church Presidency which stated "The attitude of the church with reference to negroes ... is not a matter of the declaration of a policy but of direct commandment from the Lord ... to the effect that negroes ... are not entitled to the priesthood".[155]

The church leadership did not issue a repudiation, and so in 1997 Jackson, aided by other church members including Armand Mauss, sent a second request to church leaders, which stated that white Mormons felt that the 1978 revelation resolved everything, but that black Mormons react differently when they learn the details. He said that many black Mormons become discouraged and leave the church or become inactive. "When they find out about this, they exit... You end up with the passive African Americans in the church".[156]

Other black church members think giving an apology would be a "detriment" to church work and a catalyst to further racial misunderstanding. African-American church member Bryan E. Powell says "There is no pleasure in old news, and this news is old." Gladys Newkirk agrees, stating "I've never experienced any problems in this church. I don't need an apology. . . . We're the result of an apology."[157] The large majority of black Mormons say they are willing to look beyond the previous teachings and remain with the church in part because of its powerful, detailed teachings on life after death.[158]

Church president Hinckley told the Los Angeles Times: "The 1978 declaration speaks for itself ... I don't see anything further that we need to do". Church leadership did not issue a repudiation.[155] Apostle Dallin H. Oaks said: "It's not the pattern of the Lord to give reasons. We can put reasons to commandments. When we do we're on our own. Some people put reasons to [the ban] and they turned out to be spectacularly wrong. There is a lesson in that .... The lesson I've drawn from that, I decided a long time ago that I had faith in the command and I had no faith in the reasons that had been suggested for it .... I'm referring to reasons given by general authorities and reasons elaborated upon [those reasons] by others. The whole set of reasons seemed to me to be unnecessary risk taking .... Let's [not] make the mistake that's been made in the past, here and in other areas, trying to put reasons to revelation. The reasons turn out to be man-made to a great extent. The revelations are what we sustain as the will of the Lord and that's where safety lies."[159]

Humanitarian aid in Africa

The church has been involved in several humanitarian aid projects in Africa. On January 27, 1985, members across the world joined together in a fast for "the victims of famine and other causes resulting in hunger and privation among people of Africa." They also donated the money that would have been used for food during the fast to help those victims, regardless of church membership.[160][161]:1730–1 Together with other organizations such as UNICEF and the American Red Cross, the church is working towards eradicating measles. Since 1999, there has been a 60 percent drop in deaths from measles in Africa.[162] Due to the church's efforts, the American Red Cross gave the First Presidency the organization's highest financial support honor, the American Red Cross Circle of Humanitarians award.[163] The church has also been involved in humanitarian aid in Africa by sending food boxes,[164] digging wells to provide clean water,[165] distributing wheelchairs,[166] fighting AIDS, providing Neonatal Resuscitation Training,[167] and setting up employment resources service centers.[168]

Black membership

The church has never kept official records on the race of its membership, so exact numbers are unknown. Black people have been members of Mormon congregations since its foundation, but in 1964 its black membership was small, with about 300 to 400 black members worldwide.[169] In 1997, there were approximately 500,000 black members of the church (about 5% of the total membership), mostly in Africa, Brazil and the Caribbean.[170] Since then, black membership has grown, especially in West Africa, where two temples have been built,[171] doubling to about 1 million black members worldwide.[169]

Regarding the LDS Church in Africa, professor Philip Jenkins noted that LDS growth has been slower than that of other churches,[172]:pp.2,12 citing a variety of factors, including the fact that some European churches benefited from a long-standing colonial presence in Africa;[172]:p.19 the hesitance of the LDS church to expand missionary efforts into black Africa during the priesthood ban, resulting in "missions with white faces";[172]:pp.19–20 the observation that the other churches largely made their original converts from native non-Christian populations, whereas Mormons often draw their converts from existing Christian communities;[172]:pp.20–21 and special difficulties accommodating African cultural practices and worship styles, particularly polygamy, which has been renounced categorically by the LDS Church,[172]:p.21 but is still widely practiced in Africa.[173] Commenting that other denominations have largely abandoned trying to regulate the conduct of worship services in black African churches, Jenkins wrote that the LDS Church "is one of the very last churches of Western origin that still enforces Euro-American norms so strictly and that refuses to make any accommodation to local customs."[172]:p.23

By the 2010s, LDS Church growth was over 10% annually in Ghana, Ivory Coast and some other countries in Africa. This was accompanied by some of the highest retention rates of converts anywhere in the church. At the same time, from 2009 to 2014, half of LDS converts in Europe were immigrants from Africa.[174]

In the United States, researchers Newell G. Bringhurst and Darron T. Smith, in their 2004 book Black and Mormon, wrote that since the 1980s "the number of African American Latter-day Saints does not appear to have grown significantly. Worse still, among those blacks who have joined, the average attrition rate appears to be extremely high." They cite a survey showing that the attrition rate among African American Mormons in two towns is estimated to be between 60 and 90%.[175]:p.7 There are about 180,000 self-identified black members in the U.S., or 3% of the overall U.S. membership,[176][177] with 9% of LDS converts in the US being black, while almost no lifelong Mormons are black.[178]

Mormon fundamentalism

Some Mormon fundamentalist sects that split from the LDS Church in the early 1900s continue to teach that the priesthood should be withheld from black people because of their cursed state, and that the LDS Church's reversal is a sign of its apostasy. In the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS Church), the largest of the fundamentalist Mormon denominations, church president Warren Jeffs, has been quoted as making the following declarations on the issue:[179]

- "The black race is the people through which the devil has always been able to bring evil unto the earth."

- "[Cain was] cursed with a black skin and he is the father of the Negro people. He has great power, can appear and disappear. He is used by the devil, as a mortal man, to do great evils."

- "Today you can see a black man with a white woman, et cetera. A great evil has happened on this land because the devil knows that if all the people have Negro blood, there will be nobody worthy to have the priesthood."

- "If you marry a person who has connections with a Negro, you would become cursed."

- ""I was watching a documentary one day and on came these people talking about a certain black man. ... And then it showed the modern rock group, the Beatles. ... And so the manager of the group called in this Negro, homosexual, on drugs, and the Negro taught them how to do it. And what happened then, it went world wide... . So when you enjoy the [rock] beat ... you are enjoying the spirit of the black race and that's what I emphasize to the students. And it is to rock the soul and lead the person to immorality, corruption, to forget their prayers, to forget God. And thus the whole world has partaken of the spirit of the Negro race, accepting their ways."

These and other statements have resulted in the FLDS Church being labelled a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

See also

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Collier, Fred C., ed. (1987). The Teachings of President Brigham Young. Vol 3. 1852-1854. Salt Lake City, UT: Collier's Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0934964012.

- 1 2 3 Horace Greeley (July 13, 1859). "Two Hours With Brigham Young".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Young, Brigham (1863).

Journal of Discourses/Volume 10/The Persecutions of the Saints, etc.. Wikisource. pp. 104-111.

Journal of Discourses/Volume 10/The Persecutions of the Saints, etc.. Wikisource. pp. 104-111. - 1 2 3 Bush, Lester E., Jr. (Spring 1973), "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview" (PDF), Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 8 (1): 18–19

- ↑ Arnold K. Garr, "Joseph Smith: Campaign for President of the United States", Ensign February 2002.

- ↑ Collier, Fred C., ed. (1987). The Teachings of President Brigham Young. Vol 3. 1852-1854. Salt Lake City, UT: Collier's Publishing Co. p. 46. ISBN 978-0934964012.

I will not consent for a moment to have the children of Cain rule me nor my brethren. No, it is not right... No man can vote for me or my brethren in this Territory who has not the privilege of acting in Church affairs.

- ↑ Collier, Fred C., ed. (1987). The Teachings of President Brigham Young. Vol 3. 1852-1854. Salt Lake City, UT: Collier's Publishing Co. p. 46. ISBN 978-0934964012.

Again to the subject before us; as to the [Negro] men bearing rule; not one of the children of old Cain have one particle of right to bear rule in the government affairs from first to last; they have no business there, this privilege was taken from them by their own transgressions.

- 1 2 Young, Brigham (1987), Collier, Fred C., ed., The Teachings of President Brigham Young: Vol. 3 1852–1854, Salt Lake City, Utah: Colliers Publishing Company, ISBN 0934964017, OCLC 18192348,

let my seed mingle with the seed of Cain, and that brings the curse upon me and upon my generations; we will reap the same rewards with Cain. In the Priesthood I will tell you what it will do. Were the children of God to mingle their seed with the seed of Cain it would not only bring the curse of being deprived of the power of the priesthood upon themselves but they entail it upon their children after them, and they cannot get rid of it.

- 1 2 Horace Greeley. An Overland Journey, from New York to San Francisco, in the Summer of 1859. p. 243.

I think I never heard, from the lips or journals of any of your people, one word in reprehension of that gigantic national crime and scandal, American Chattel slavery. You speack forcibly of the wrongs to whuch your feeble brethren have from time to time been subjected; but what are they all to the perpetual, the gigantic outrage involved in holding in abject bondage four millions of human beings?

- 1 2 United States. Congress (1857). The Congressional Globe, Part 2. Blair & Rives. p. 287.

- ↑ Harris, Hamil R. (February 17, 2012). "Mindful of history, Mormon Church reaches out to minorities". Washington Post. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

a period of more than 120 years during which black men were essentially barred from the priesthood and few Americans of color were active in the faith.

- 1 2 Ostling, Richard, and Joan K. Ostling (2007). Mormon America: The Power and the Promise. New York: HarperCollins. p. 102. ISBN 978-0061432958.

- ↑ Mauss (2003, pp. 219–227) (comparing 1960s survey responses of Mormons versus non-Mormons) "On the whole, Mormons were not very different from other Americans in holding rather conservative views on civil rights for blacks. On internal church questions, not all of the Saints were happy about the priesthood restriction, and many had serious doubts about other traditional teachings relating to black people. However, when pressure mounted from the outside, Mormons tended to defend their church out of loyalty, whatever their doubts."

- ↑ Bringhurst, Newell G.; Smith, Darron T., eds. (2004). Black and Mormon. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02947-X.

- 1 2 3 4 Mauss, Armand (2003). "The LDS Church and the Race Issue: A Study in Misplaced Apologetics". FAIR.

- ↑ Richard Bushman (2008). Mormonism: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Gordon B. Hinckley, "The Need for Greater Kindness", Liahona, May 2006, pp. 58–61.

- ↑ Adherents.com quoting Deseret News 1999-2000 Church Almanac. Deseret News: Salt Lake City, Utah (1998); p. 119. "A rough estimate would place the number of Church members with African roots at year-end 1997 at half a million, with about 100,000 each in Africa and the Caribbean, and another 300,000 in Brazil."

- ↑ "Saints, Slaves, and Blacks" by Bringhurst. Table 8 on p.223

- ↑ Coleman, Ronald G. (2008). "'Is There No Blessing For Me?': Jane Elizabeth Manning James, a Mormon African American Woman". In Taylor, Quintard; Moore, Shirley Ann Wilson. African American Women Confront the West, 1600-2000. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 144–162. ISBN 978-0806139791.

Jane Elizabeth James never understood the continued denial of her church entitlements. Her autobiography reveals a stubborn adherence to her church even when it ignored her pleas.

- ↑ Mauss (2003, p. 213)

- 1 2 Bush, Lester E.; Mauss, Armand L. (1984). "3". Neither White nor Black.

- 1 2 3 4 Larry G. Murphy, J. Gordon Melton, and Gary L. Ward (1993). Encyclopedia of African American Religions (New York: Garland Publishing) pp. 471–472.

- 1 2 3 4 Newell G. Bringhurst (1981). Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People within Mormonism (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press).

- ↑ Connell O'Donovan, "The Mormon Priesthood Ban & Elder Q. Walker Lewis: 'An example for his more whiter brethren to follow', John Whitmer Historical Association Journal, 2006.

- ↑ "Its nothing to do with the blood for [from] one blood has God made all flesh, we have to repent [to] regain what we have lost—we have one of the best Elders, an African in Lowell [referring to Walker Lewis].": Brigham Young Papers, March 26, 1847, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- ↑ General Minutes, April 25, 1847, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- ↑ Mauss (2003, p. 215)

- ↑ Mauss (2003, pp. 213–15) ("Both Smith and Young, like their contemporary Abraham Lincoln, would be considered "racists" by today's norms because they all believed in the natural and inherent inferiority of Africans")

- ↑ Matthew Bowman (2012). The Mormon People. Random House. p. 176.

- ↑ Peggy Fletcher Stack. "Black Mormon pioneers — a rich but forgotten legacy of faith". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kristen Rogers-Iversen (September 2, 2007). "Utah settlers' black slaves caught in 'new wilderness'". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- 1 2 3 John David Smith. Dictionary of Afro-American Slavery.

- 1 2 "Brief History Alex Bankhead and Marinda Redd Bankhead (mention of Dr Pinney of Salem)". The Broad Ax. March 25, 1899.

- ↑ Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel:John Hardison Redd

- ↑ John Todd. Early Settlement and Growth of Western Iowa; Or, Reminiscences. pp. 134–137.

- 1 2 3 Don B. Williams. Slavery in Utah Territory: 1847-1865.

- ↑ Slavery in Utah

- ↑ Flake, Joel. "Green Flake: His Life and Legacy" (1999) [Textual Record]. Americana Collection, Box: BX 8670.1 .F5992f 1999, p. 8. Provo, Utah: L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

- ↑ Brigham Young told Greeley: "If slaves are brought here by those who owned them in the states, we do not favor their escape from the service of their owners." (see Greeley, Overland Journey 211-212) quoted in Terry L. Givens, Philip L. Barlow. The Oxford Handbook of Mormonism. p. 383.

- ↑ History of the Church, 4:544.

- ↑ Millennial Star, February 15, 1851. Quoted in BlackLDS.org

- 1 2 3 Young, Brigham (1863).

Journal of Discourses/Volume 10/Necessity for Watchfulness, etc.. Wikisource. pp. 248-250.

Journal of Discourses/Volume 10/Necessity for Watchfulness, etc.. Wikisource. pp. 248-250. - ↑ Young, Brigham (1863).

Journal of Discourses/Volume 10/Knowledge, Correctly Applied, the True Source of Wealth and Power, etc.. Wikisource. pp. 191. "In the providences of God their ability is such that they cannot rise above the position of a servant."

Journal of Discourses/Volume 10/Knowledge, Correctly Applied, the True Source of Wealth and Power, etc.. Wikisource. pp. 191. "In the providences of God their ability is such that they cannot rise above the position of a servant." - ↑ Bigler, David L. (1998). Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847-1896. Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 0-87062-282-X.

- ↑ Brigham Young (January 23, 1852). "We Must Believe in Slavery". (see also The Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, ed. Richard S. Van Wagoner (Salt Lake City: Smith-Pettit Foundation, 2009), 1:473-74; The Teachings of President Brigham Young, Volume 3: 1852-1854, comp. and ed. Fred C. Collier (Salt Lake City: Collier’s Publishing, 1987), 26-29.)

- ↑ Negro Slaves in Utah by Jack Beller, Utah Historical Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 4, 1929, pp. 124-126

- 1 2 Nicholas R. Cataldo (1998). "Former Slave Played Major Role In San Bernardino's Early History:Lizzy Flake Rowan". City of San Bernardino.

- ↑ "The Latter-Day Saints' Millennial Star, Volume 17". p. 63.

Most of those who take slaves there pass over with them in a little while to San Bernardino... How many slaves are now held there they could not say, but the number relatively was by no means small. A single person had taken between forty and fifty, and many had gone in with smaller numbers.

- ↑ Mark Gutglueck. "Mormons Created And Then Abandoned San Bernardino". San Bernadino County Sentinel.

- ↑ Camille Gavin (2007). Biddy Mason: A Place of Her Own. America Star Books.

- ↑ Benjamin Hayes. "Mason v. Smith".

none of the said persons of color can read and write, and are almost entirely ignorant of the laws of the state of California as well as those of the State of Texas, and of their rights

- ↑ Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, South Carolina and Alabama repealed their laws during the Reconstruction period, but the laws were later reinstated and remained in force until 1967.

- ↑ Phelps, W. W. (1835).

Latter Day Saints' Messenger and Advocate/Volume 1/Number 6/Letter to Oliver Cowdery from W. W. Phelps (Feb. 6, 1835). Wikisource. pp. 82. "Canaan, after he laughed at his grand father's nakedness, heired three curses: one from Cain for killing Abel; one from Ham for marrying a black wife, and one from Noah for ridiculing what God had respect for"

Messenger and Advocate 1:82

Latter Day Saints' Messenger and Advocate/Volume 1/Number 6/Letter to Oliver Cowdery from W. W. Phelps (Feb. 6, 1835). Wikisource. pp. 82. "Canaan, after he laughed at his grand father's nakedness, heired three curses: one from Cain for killing Abel; one from Ham for marrying a black wife, and one from Noah for ridiculing what God had respect for"