Bonny Norton

| Bonny Norton | |

|---|---|

|

Bonny Norton | |

| Born |

1956 Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Fields | language education, applied linguistics, literacy and development |

| Institutions | University of British Columbia |

| Known for | identity and language learning, learner investment, mentorship |

| Notable awards | FRSC |

|

Website http://faculty.educ.ubc.ca/norton/ | |

Bonny Norton, FRSC is a Professor and Distinguished University Scholar in the Department of Language and Literacy Education, University of British Columbia, Canada. She is also Research Advisor of the African Storybook and 2006 co-founder of the Africa Research Network on Applied Linguistics and Literacy. She is internationally recognized for her theories of identity and language learning and her construct of investment. A Fellow of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), she was the first recipient in 2010 of the Senior Research Leadership Award of AERA’s Second Language Research SIG. In 2016, she was awarded the TESOL Award for Distinguished Research and named a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Biography

Born in 1956 and raised in South Africa during the turbulent apartheid years, Norton learnt at an early age the complex relationship between language, power, and identity. As a reporter for the student newspaper at the University of the Witwatersrand (WITS) in Johannesburg, she investigated the draconian language policies of the state, which sought to impose the Afrikaans language on resistant African students, precipitating the Soweto Riots in 1976. After completing a BA in English and History, a teaching diploma, and an Honours Degree in Applied Linguistics at WITS in 1982, she received a Rotary Foundation Graduate Scholarship to do an MA in Linguistics (1984) at Reading University in the UK. Thereafter she joined her partner, Anthony Peirce, in Princeton University, USA, where she spent three years as a TOEFL language test developer at the Educational Testing Service, and had two children, Michael and Julia. The family moved to Canada in 1987, where Norton completed a PhD in Language Education (1993) at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto. Prior to her appointment at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in 1996, she was awarded Postdoctoral Fellowships from the USA National Academy of Education Spencer Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Research Program

Norton is centrally concerned with the ways in which language and literacy research can address larger social inequities, while supporting educational change at the grassroots level. Her research seeks to make visible the relations of power that language learners and teachers navigate in diverse classrooms and communities.[1][2] An advocate for international development, her trajectory of research extends from Canada to sub-Saharan Africa, focussing on a broad range of topics including digital literacy, popular culture, health literacy, language assessment, and teacher education. In 2006, she co-founded the Africa Research Network on Applied Linguistics and Literacy, and is active in the innovative African Storybook in which her former UBC graduate students, Juliet Tembe and Sam Andema, are team members.[3][4] The ASP is an open-access digital initiative of the South African Institute for Distance Education, which promotes early literacy for African children through the provision of hundreds of children’s stories in multiple African languages, as well as English, French, and Portuguese. Its spin-off, the Global-ASP, is translating these stories for children worldwide. In her capacity as Research Advisor of the African Storybook, Norton has worked with Espen Stranger-Johannessen, also of UBC, to initiate the African Storybook blog and YouTube channel to advance this and other projects.

Key ideas

Norton has been recognized for her commitment to social and educational change through the investigation of identity categories such as gender, race, and class in language learning contexts.[5] She investigates how language learners can be positioned by others, and how these learners can claim more powerful identities from which to speak, read, and write a second or foreign language. By theorizing the complex relationship between the language learner and the social world, Norton is a central figure in the “social turn” of second language acquisition. Three of her key ideas address identity, investment, and imagined communities.[6]

Identity and language learning

Based on a study of adult immigrants in Canada, Norton’s seminal article, “Social identity, investment, and language learning” published in the TESOL Quarterly in 1995[7] and her book Identity and Language Learning[8] have been pivotal in establishing the theoretical relevance of identity in language education research. Extending the work of poststructuralist Christine Weedon (1987) on subjectivity and social theorist Pierre Bourdieu (1991) on legitimate language, Norton defines identity as “how a person understands his or her relationship to the world, how that relationship is structured across time and space, and how the person understands possibilities for the future”.[9] Norton asserts that when language learners speak, they are not only exchanging information with others, but are constantly reconfiguring their relationship to the social world. Hence, language is theorized as both a linguistic system and a social practice, and identity as multiple, changing and often a site of struggle. As learners participate in different contexts as mother, student, employee or immigrant, relations of power impact not only their access to communities and social networks, but also the ways in which they interact with target language speakers. How learners are positioned by virtue of gender, race, class, or sexual orientation can constrain or enable their opportunities to speak and be heard. Norton asserts that it is by reframing inequitable relationships with interlocutors that learners can claim identities as legitimate speakers.

Investment: Identity, capital, ideology

In the early 1990s when psychological theories of motivation dominated analyses of how languages are learned, learners were often defined in binary terms as motivated or unmotivated, introverted or extroverted, inhibited or uninhibited, with little reference to unequal relations of power between language learners and target language speakers. Recognizing that identity is multiple and changing, Norton saw the need to develop the sociological construct of investment to signal the socially and historically constructed relationship of learners to the target language, and the way relations of power are implicated in language learning and teaching.

Drawing on Bourdieu’s theories of capital, language, and symbolic power, Norton argues that if learners invest in a target language, they do so with the understanding that they will acquire a wider range of symbolic and material resources, which will increase the value of their cultural capital and social power. Unlike constructs of motivation, which frequently conceive of the language learner as having a unitary, fixed, and ahistorical “personality,” the construct of investment conceives of the language learner as having a complex identity, changing across time and space, and reproduced in social interaction.

As a theoretical tool, investment helps examine the conditions under which social interaction takes place, and the extent to which relations of power enable or constrain opportunities for language learners to speak. In this view, learners can be highly motivated to learn a language, but may not necessarily be invested in the language practices of a given classroom or community if their practices are, for example, racist or sexist. In addition to asking, “Are students motivated to learn a language?” researchers and teachers pose the question, “To what extent are students invested in the language and literacy practices of the classroom?” Because identity is often a site of struggle, investment can be complex and contradictory.

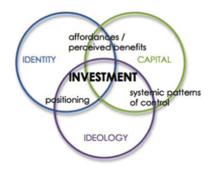

Responding to a more mobile, digital world where learners move between online and offline spaces with greater fluidity, Norton has extended her theorization of investment to address a changing linguistic landscape. Together with her student Ron Darvin, she has constructed a model of investment that locates investment at the intersection of identity, capital, and ideology.[10] This model serves as a framework to understand how the skills, knowledge, and resources that learners possess are valued differently across multiple spaces, and to draw attention to how ideologies operate on micro and macro levels. It examines how institutional processes and patterns of control shape what becomes regular practice, and how learners can question, challenge and reposition themselves in these spaces to claim the right to speak.

A great number of scholars from different parts of the world have turned to investment to examine how power operates in language learning contexts, and journal special issues have been devoted to this construct in China[11] and francophone Europe.

Imagined communities and imagined identities

Norton recognizes that identity is shaped not only by material conditions and lived experiences, but also by learners’ imagined futures and imagined identities. She asserts that learners invest in particular language and literacy practices because of their desire to be affiliated with a given target language community. While Benedict Anderson focused on the theorization of the nation as an imagined community, Norton considers that a wide range of imagined communities can be desirable, from membership in a local book club or successful professional network to an online transnational community.[12] By imagining themselves allied with others across time and space, language learners are encouraged to seek opportunities for social interaction through diverse language and literacy practices. Norton argues that such imagined communities can be even more powerful than face-to-face communities in shaping the investment of learners. She argues further that a lack of awareness of learners’ imagined communities and imagined identities could hinder a teacher’s ability to construct productive language learning activities. The constructs of imagined communities and imagined identities have been further developed,[13][14] and have proved productive in a range of research contexts.[15]

Books and journal special issues

- Norton, B. (Guest Ed.) (2014). Multilingual literacy and social change in African communities [Special issue]. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(7).

- Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. 2nd edition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Higgins, C. & Norton, B. (Eds.) (2010). Language and HIV/AIDS. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (Eds). (2004). Critical pedagogies and language learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Norton, B., & Pavlenko, A. (Eds.). (2004). Gender and English language learners. Alexandria, VA: TESOL Publications.

- Kanno, Y., & Norton, B. (Guest Eds.). (2003). Imagined communities and educational possibilities [Special issue]. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 2(4).

- Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Harlow, England: Longman/Pearson Education.

- Norton, B. (Guest Ed.). (1997). Language and identity [Special issue]. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3).

Recent awards

Major recent awards/distinctions include:[16]

- Named a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada[17][18]

- TESOL Award for Distinguished Research, 2016. https://www.tesol.org/enhance-your-career/tesol-awards-honors-grants/tesol-awards-for-excellence-service/tesol-award-for-distinguished-research

- Beijing Foreign Studies University Distinguished Visiting Scholar, 2015

- Vernon Pack Distinguished Scholar and Convocation Speaker, Otterbein University, Ohio, 2015[19]

- Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies Distinguished Scholar in Residence, UBC, 2013/2014[20]

- Research Advisor, African Storybook, South African Institute for Distance Education, 2013 to present

- American Educational Research Association Fellow, 2012[21]

- AERA Second Language Research SIG, Senior Research Leadership Award (inaugural recipient), 2010

- Visiting Senior Research Fellow, King's College London, 2007–2010

- Honorary Professor, Education, University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, 2007–2010[22]

- UBC Killam Research Prize, 2007[23]

- UBC Distinguished University Scholar, 2004 to present

- UBC Killam Teaching Prize, 2003[24]

References

- ↑ "Language practices in classroom can help motivate students, says Institute scholar". Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies. 2013.

- ↑ "Bonny Norton, The University of British Columbia" (PDF). Royal Society of Canada. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Faculty of Education: Community Engagement

- ↑ Allen, C. (March 19, 2014). "A new digital storytelling project promotes literacy and preserves local folklore in Africa". UBC News.

- ↑ Higgins, C. (2013). "Norton, Bonny". In C. Chapelle (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 1–3. ISBN 9781405198431.

- ↑ Kramsch, C. (2013). "Afterword". In B. Norton. Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters. pp. 192–201.

- ↑ Norton, B. (1995). "Social identity, investment, and language learning". TESOL Quarterly. 29 (1): 9–31.

- ↑ Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters.

- ↑ Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters. p. 4.

- ↑ Darvin, R.; Norton, B. (2015). "Identity and a model of investment in applied linguistics". Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. 35: 192–201.

- ↑ Arkoudis, S.; Davison, C. (Guest Eds.) (2008). "Chinese Students: Perspectives on their social, cognitive, and linguistic investment in English medium interaction [Special Issue]". Journal of Asian Pacific Communication. 18 (1).

- ↑ Norton, B. (2001). "Non-participation, imagined communities, and the language classroom". In M. Breen (Ed.). Learner contributions to language learning: New directions in research. Harlow, England: Pearson Education. pp. 159–171.

- ↑ Kanno, Y.; Norton, B. (2003). "Imagined communities and educational possibilities: Introduction". Journal of Language, Identity & Education. 2 (4): 241–249.

- ↑ Pavlenko, A.; Norton, B. (2007). "Imagined communities, identity, and English language learning". In J. Cummins; C. Davidson (Eds.). International handbook of English language teaching. New York: Springer. pp. 669–680.

- ↑ Norton, B.; Toohey, K. (2011). "Identity, language learning, and social change". Language Teaching. 44 (4): 412–446.

- ↑ Norton, B. "Bonny Norton".

- ↑ "NORTON, BONNY - THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA". Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "UBC FACULTY NAMED 2016 FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF CANADA". Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "Vernon L. Pack Distinguished Lecture Series". Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "Distinguished Scholars in Residence". Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "AERA Honors 2012 Fellows for Outstanding Education Research" (PDF). Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. The Oxford Handbook of Applied Linguistics. Oxford University. p. 27.

- ↑ "Faculty Research Award Winners" (PDF). Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ "UBC Killam Teaching Award 2003". Retrieved 9 November 2015.

Further reading

- Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change (PDF). Harlow, England: Longman/Pearson Education. ISBN 0582382254.

- Norton, B.; Welch, T. (May 14, 2015). "Digital stories could hold the key to multilingual literacy for African children". The Conversation.

External links

- Bonny Norton's home page

- Bonny Norton on Google Scholar

- Bonny Norton's Youtube channel

- African Storybook

- African Storybook blog

- Applied Linguistics and Literacy in Africa & the Diaspora Research Network

- GCLR 2013 Webinar "Identity, Investment, and Multilingual Literacy (in a digital world)"