Bowery Boys

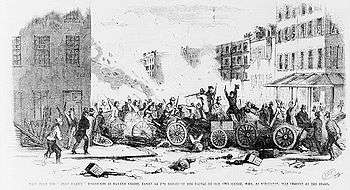

A view of the notorious 1857 fight between the "Bowery Boys" and the "Dead Rabbits" in the Sixth Ward, New York City | |

| Founded by | William "Bill the Butcher" Poole |

|---|---|

| Founding location | Bowery, Manhattan, New York City |

| Years active | Mid-19th century |

| Territory | The Bowery, Manhattan, New York City |

| Ethnicity | English-American |

| Membership (est.) | ? |

| Criminal activities | street fighting, assault, murder, robbery, arson, rioting |

| Rivals | Dead Rabbits, Plug Uglies |

The Bowery Boys were a nativist, anti-Catholic, and anti-Irish gang based out of the Bowery neighborhood of Manhattan in the mid-19th century. Despite its reputation as one of the most notorious street gangs of New York City at the time, the majority of the Bowery Boys led law-abiding lifestyles for most of the week. The gang was made up exclusively of volunteer firemen, though some also worked as mechanics and butchers (the primary trade of founder William "Bill the Butcher" Poole), and would fight rival fire companies over who would extinguish a fire. While acting in capacity as a gang (and aided by other Bowery gangs), the Bowery Boys often battled multiple outfits of the infamous Five Points, most notably the Dead Rabbits, with whom they would feud for decades. The uniform of a Bowery Boy generally consisted of a stovepipe hat in variable condition, a red shirt, and dark trousers tucked into boots, this style paying homage to their roots as volunteer firemen.

Mike Walsh

Mike Walsh was largely considered the leader of the Bowery Boys.[1] Walsh acted as a political figure to the Bowery Boys and even became an elected official. He reached the peak of his popularity in 1843, when he created the political clubhouse he called the "Spartan Association", which consisted of factory workers and unskilled laborers.[2] Walsh felt that political leaders were treating the poor unfairly and wanted to make a difference by becoming a leader himself. Walsh was sentenced to jail twice, but the Bowery Boys became so powerful that they were able to bail him out during his second trip to jail. The front page of The Subterranean on April 4th read, "We consider the present infamous persecution of Mike Walsh a blow aimed at the honest laboring portion of this community".[3] Due to the threat of violence in the streets, Walsh was let out midway through his sentence. Walsh was considered by many to be the "champion of the poor man's rights". Walsh was eventually taken to Tammany Hall and was nominated for a seat in the state legislature, and even earned the support of poet Walt Whitman. Walsh eventually died in 1859 and his obituary in an edition of The Subterranean read that the leader of the Bowery Boys was an "original talent, rough, full of passionate impulses... but he lacked balance, caution-the ship often seemed devoid of both ballast and rudder". The obituary was thought to be written by Whitman.[4]

Bowery Boys in the theater

The Bowery Boys were known to frequent theaters in New York City. Richard Butsch from The Making Of American Audience's said that, "they brought the street into the theater, rather than shaping the theater into an arena of the public sphere".[5] The Bowery Theater, in particular, was a favorite among the Bowery Boys. The Bowery Theater was built in 1826 and soon became a theater for the working man. Walt Whitman described the theater as "packed from ceiling to pit with its audience, mainly of alert, well-dressed, full-blooded young and middle aged men, the best average of American-born mechanics".[6] Plays even began to appear in theaters frequented by the Bowery Boys with shows about Bowery Boys themselves. Particularly, a character named Moses who many Bowery Boys deemed as "the real thing".[7] It was not uncommon for men to drink, smoke, and meet with prostitutes in the theater. The Bowery Boys dominated the theater in the early 19th century and theater was considered to be a "male club".[8]

In popular culture

- The main character of Patricia Beatty's 1987 historical children's fiction novel Charley Skedaddle is a Bowery Boy before enlisting as a drummer in the Union army.

- The 2002 Martin Scorsese film Gangs of New York features a semi-fictionalized version of "Bill the Butcher" as a central character and uses the feud between the Bowery Boys and Dead Rabbits as a central plot point.

See also

- William Poole

- B'hoy and g'hal

- The Bowery Boys (Hollywood films (1946-1958)

- The Bowery Boys: New York City History (audio podcast)

Further reading

- Adams, Peter. The Bowery Boys: Street Corner Radicals and the Politics of Rebellion. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-275-98538-5

References

- ↑ Adams, Peter (2005). The Bowery Boys: Street Corner Radicals and the Politics of Rebellion. Praeger. p. 1.

- ↑ Adams, Peter (2005). The Bowery Boys: Street Corner Radicals and the Politics of Rebellion. Praeger. p. 1.

- ↑ Adams, Peter (2005). The Bowery Boys: Street Corner Radicals and the Politics of Rebellion. Praeger. p. 2.

- ↑ Adams, Peter (2005). The Bowery Boys: Street Corner Radicals and the Politics of Rebellion. Praeger. p. 3.

- ↑ Butsch, Richard. The Making of American Audiences. p. 44.

- ↑ Butsch, Richard. The Making of American Audiences. p. 46.

- ↑ Butsch, Richard. The Making Of American Audiences: From Stage To Television.

- ↑ Butsch, Richard. Bowery B'hoys and Matinee Ladies: The Re-Gendering of Nineteenth-Century American Theater Audiences.

- Asbury, Herbert. The Gangs of New York. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928. ISBN 1-56025-275-8

- Sifakis, Carl. The Encyclopedia of American Crime. New York: Facts on File Inc., 2001. ISBN 0-8160-4040-0