Bridget Bate Tichenor

| Bridget Bate Tichenor | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Bridget Bate Tichenor by George Platt Lynes, New York 1945. | |

| Born |

Bridget Pamela Arkwright Bate November 22, 1917 Paris, France |

| Died |

October 20, 1990 (aged 72) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican (Mexico) |

| Education | Slade School of Fine Art, École des Beaux Arts, Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Painting, Fashion editor |

| Notable work | Domadora de quimeras, Caja de crystal, Los encarcelados, Líderes |

| Movement | Surrealism, magic realism |

Bridget Bate Tichenor (born Bridget Pamela Arkwright Bate on November 22, 1917 – died on October 20, 1990), also known as Bridget Tichenor or B.B.T., was a Mexican surrealist painter of fantastic art in the school of magic realism and a fashion editor. Born in Paris and of British descent, she later embraced Mexico as her home.[1]

Family and early life in Europe

Bate was the daughter of Frederick Blantford Bate (c1886-1970) and Vera Nina Arkwright (1883-1948), who was also known as Vera Bate Lombardi. Although born in France, she spent her youth in England and attended schools in England, France, and Italy. She moved to Paris at age 16, to live with her mother, where she worked as a model for Coco Chanel.[2] She lived between Rome and Paris from 1930 until 1938.

Fred Bate carefully guided his daughter with her art. He recommended she attend the Slade School in London, and visited her later at the Contembo Ranch in Mexico. Fred Bate's close friend, surrealist photographer Man Ray, photographed her at different stages of her modeling career from Paris to New York.[3][4]

Vera Bate Lombardi is said to have been the public relations liaison to the royal families of Europe for Coco Chanel between 1925 and 1938.[2] Her grandmother, Rosa Frederica Baring (1854-1927) was a member of the Baring banking family, being a great granddaughter of Sir Francis Baring (1740-1810), the founder of Barings Bank, and Bridget Bate was therefore related to many British and European aristocratic families.[5]

New York and the United States

Bate married Hugh Joseph Chisholm at the Chisholm family home, Strathgrass in Port Chester, New York on October 14, 1939.[6] It was an arranged marriage, devised by her mother Vera through Cole Porter and his wife Linda's introduction, in order to remove Bate from Europe and the looming threat of the World War II.[7] They had a son in Beverly Hills, California on December 21, 1940 named Jeremy Chisholm.[8] H. Jeremy Chisholm was a noted businessman and equestrian in the USA, United Kingdom and Europe, who was married to Jeanne Vallely-Lang Suydam and father to James Lang-Suydam Chisholm when he died in Boston in 1982.[9][10]

In 1943, Bate was a student at the Art Students League of New York and studying under Reginald Marsh along with her friends, the painters Paul Cadmus and George Tooker.[11] Acquaintances have described Bate during this time as "striking",[12] "glamorous",[11] and a "long-stemmed beauty with large azure eyes and sumptuous black hair".[13] She lived in an apartment at the Plaza Hotel and wore clothes by Manhattan couturier Hattie Carnegie.[14] It was around this time that the author Anaïs Nin wrote about her infatuation with Bate in her personal diary.[15][16] Bate was at a party in the Park Avenue apartment of photographer George Platt Lynes, a friend who used her as a subject in his photographs, when she met Lynes' assistant, Jonathan Tichenor, in 1943.[14] They started an affair in 1944 when her husband was away and working overseas for the US government. She divorced Chisholm on December 11, 1944 and moved into an Upper East Side townhouse in Manhattan that she shared with art patron Peggy Guggenheim.[17] She married Jonathan Tichenor in 1945, taking his last name to become known as Bridget Bate Tichenor, and they moved into an artist's studio at 105 MacDougal Street in Manhattan.[17]

Painting technique

Bate Tichenor's painting technique was based upon 16th-century Italian tempera formulas that artist Paul Cadmus taught her in New York in 1945, where she would prepare an eggshell-finished gesso ground on masonite board and apply (instead of tempera) multiple transparent oil glazes defined through chiaroscuro with sometimes one hair of a #00 sable brush.[15] Bate Tichenor considered her work to be of a spiritual nature, reflecting ancient occult religions, magic, alchemy, and Mesoamerican mythology in her Italian Renaissance style of painting.[18]

Life in Mexico

The cultures of Mesoamerica and her international background would influence the style and themes of Bate Tichenor's work as a magic realist painter in Mexico.[19] She was among a group of surrealist and magic realist female artists who came to live in Mexico in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[7] Her introduction to Mexico was through a cousin she had first met in Paris in the 1930s: Edward James, the British surrealist art collector and sponsor of the magazine Minotaure. James lived in Las Pozas, San Luis Potosí, and his home in Mexico had an enormous surrealist sculpture garden with natural waterfalls, pools and surrealist sculptures in concrete.[20] In 1947, James invited her to visit him again at his home Xilitia, near Tampico in the rich Black Olmec culture of the Gulf Coast. He had urged her for many years to receive secret spiritual initiations that he had undergone, and a lifetime change and new artistic direction resulted from her epiphanies during this trip.[12] After visiting Mexico, Bate Tichenor obtained a divorce in 1953 from her second husband, Jonathan Tichenor, and moved to Mexico in the same year, where she made her permanent home and lived for the rest of her life.[15] She left her marriage and job as a professional fashion and accessories editor for Vogue[13] behind and was now alongside expatriate painters such as Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Alice Rahon, and photographer Kati Horna.[1]

Having lived in varied European and American cultures with multiple identities reflecting her life passages, Bate Tichenor recognized the Pre-Columbian cycles of creation, destruction, and resurrection that echoed the events of the catastrophes of her own life mounted within the dismantling and reconstructive context of two World Wars.[15] The openness of Mexico at that time fueled her personal expectations of a future filled with endless artistic inspiration in a truly new world founded upon metaphysics, where a movement of societal, political, and spiritual ideals were being immortalized in the arts.[15]

At the time of Bate Tichenor's move to Mexico in 1953, she began what would become a lifetime journey through her art and mysticism, inspired by her belief in ancestral spirits, to achieve self-realization.[15] While painting alone and in isolation, she removed her familiar and societal masks to find her own personal human and spiritual identities; she would then reposition those hidden identities with new masks and characters in her paintings that represented her own sacred beliefs and truths.[15] This guarded internal process of self-discovery and fulfillment was allegorically portrayed with a cast of mythological characters engaged in magical settings. She painted a dramatization of her own life and quests on canvas through an expressive visual language and an artistic vocabulary that she kept secret.[15]

In 1958, she participated in the First Salon of Women's Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Carrington, Rahon, Varo, and other contemporary women painters of her era.[21] That same year, she bought the Contembo ranch near the remote village of Ario de Rosales, Michoacán where she painted reclusively with her extensive menagerie of pets until 1978.[7]

Bate Tichenor counted painters Carrington, Alan Glass, and artist Pedro Friedeberg among her closest friends and artistic contemporaries in Mexico.

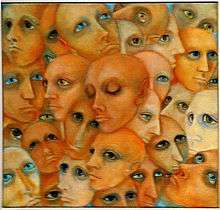

Between 1982 and 1984, Bate Tichenor lived in Rome and painted a series of paintings titled Masks, Spiritual Guides, and Dual Deities.[15] Her final years were spent at her home in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico.[15]

Contembo Ranch

The architecture of Bate Tichenor's house at Contembo Ranch in Michoacán was a simple Tuscan-style country villa cross-shaped designed brick and adobe two-story structure that she built with her Purépechan lover Roberto in 1958. Ario de Rosales was named “place where something was sent to be said”[15] in the Purépecha language. Bate Tichenor became an artistic channel for the place that she chose to call her home.[15]

Many of the faces and bodies of her magical creatures in her paintings were based upon her assorted terriers, chihuahuas, and Italian mastiffs, sheep, goats, monkeys, parrots, iguanas, snakes, horses, cows, and local Purépecha servants and friends.[15]

The light, colors and landscapes of Bate Tichenor's paintings were inspired by the topography of the volcanic land that surrounded her mountaintop home. There was a curvature of the earth that could be seen from her second-story studio where the pine tree covered red mountains cascaded towards the Pacific Ocean. There also was a waterfall with turquoise pools of water that traversed her property.[15]

Death and legacy

At the time of Bate Tichenor's death in the Daniel de Laborde-Noguez and Marie Aimée de Montalembert house on the Calle Tabasco in Mexico City in 1990, she chose to be exclusively with her close friends. Bate Tichenor's mother Vera Bate Lombardi was a close friend of Comte Léon de Laborde, who was a fervent admirer of Coco Chanel in her youth and had introduced Lombardi to Chanel. Comte Léon de Laborde's grandson, economist Carlos de Laborde-Noguez, his wife Marina Lascaris, his brother Daniel de Laborde-Noguez and his wife, Marie Aimée de Motalembert became Bate Tichenor's most respected allies, trusted friends, and caretakers at the end of her life in their home in Mexico City.[2]

Bate Tichenor was the subject of a 1985 documentary titled Rara Avis, shot in Baron Alexander von Wuthenau's home in Mexico City.[22] It was directed by Tufic Makhlouf [23] and focused on Bate Tichenor’s life in Europe, her being a subject for the photographers Man Ray, Cecil Beaton, Irving Penn, John Rawlings, George Platt Lynes, her career as a Vogue fashion editor in New York with Condé Nast art director Alexander Liberman between 1945 and 1952, and her magic realism painting career in Mexico that began in 1956.[7] The title of the film, Rara Avis, is a Latin expression that comes from the Roman poet Juvenal meaning a rare and unique bird,[24] the "black swan."[25] Rara Avis was screened at the 2008 FICM Morelia international film festival.[26]

Artist Pedro Friedeberg wrote about Bate Tichenor and their life in Mexico in his 2011 book of memoirs De Vacaciones Por La Vida (Holiday For Life), including stories of her interaction with his friends and contemporaries Salvador Dalí, Leonora Carrington, Kati Horna, Tamara de Lempicka and Edward James.[27]

Works of art

Interest in Bate Tichenor's paintings by art collectors and museums has been increasing in recent years, as well as collections of art photographs with her as the subject. Her paintings were first sold in 1954 by the Ines Amor Gallery in Mexico City, and then later by her patron, the late Mexican art dealer and collector Antonio de Souza at the Galeria Souza in the Paseo de la Reforma, Mexico City. In 1955, the Karning Gallery, directed by Robert Isaacson, represented her. In 1972 and 1974 she exhibited at the Galeria Pecanins, Colonia Roma, Mexico City. A comprehensive retrospective exhibition was held at the Instituto de Bellas Artes de San Miguel de Allende in February 1990, nine months before her death. She left 200 paintings that were divided between Pedro Friedeberg and the de Laborde-Noguez family. Her works became a part of important international private and museum collections in the United States, Mexico and Europe that included the Churchill and Rockefeller families. They were sought after for their refined esoteric nature with detail in master painting technique.[15]

Two 1941 gelatin silver print portraits of Bate Tichenor by avant-garde artist Man Ray were auctioned by Christie's London in 1996.[3] Another 1941 gelatin silver print photograph of Bate Tichenor by Man Ray was auctioned by Sotheby's New York in 1997.[4] A silver gelatin print of fashion photographer Irving Penn's 1949 photograph of Bate Tichenor and model Jean Patchett, titled The Tarot Reader, resides in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.[28] Two paintings by Bate Tichenor were auctioned by Christie’s in July, 2007 at New York's Rockefeller Plaza, and both received almost 10 times the original estimates in the auction of Mexican actress María Félix's estate.[29] Bate Tichenor's oil on canvas titled Domadora de quimeras, featuring the face of María Félix with details by painter Antoine Tzapoff, went for $20,400 USD, which was several times higher than its original low estimate of $2000 USD.[30] Another painting by Bate Tichenor, Caja de crystal, also sold for much more than its estimated price.[31]

In 2008, the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey held an exhibition of Bate Tichenor’s work, including her paintings among 50 prominent Mexican artists such as Frida Kahlo. It was titled History of Women: Twentieth-Century Artists in Mexico. The exhibition centered on women who had developed their artistic activities within individual and diverse disciplines while working in Mexico.[32]

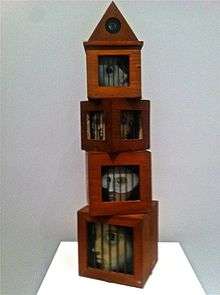

Bate Tichenor was featured in the 2012 exhibition In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States, organized by LACMA and the Museo de Arte Moderno. Included were Bate Tichenor's paintings Líderes, Autorretrato (Self-Portrait), and Los encarcelados, a tall work of four stacked wooden cages with painted masonite heads inside of each box and a pyramid on the top of the structure. The exhibition took place at the LACMA Resnick Pavilion in Los Angeles[33][34]

The Museum of the City of Mexico's director, Cristina Faesler, has organized over 100 paintings for an exhibition dedicated to Bate Tichenor in Mexico City beginning May 23, 2012 to August 5, 2012.[35] The exhibition at the Museo de la Ciudad de México is a visual monograph of Bate Tichenor's work, her surrealist vision and technique.[36]

References

- 1 2 Orenstein Ph.D., Gloria. "The Surrealist Cosmovision of Bridget Tichenor", FEMSPEC - an Interdisciplinary Feminist Journal, Issue 1.1, June 1999.

- 1 2 3 Charles-Roux, Edmonde. Chanel: Her Life, Her World, and the Woman Behind the Legend She Herself Created, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975 ISBN 0-394-47613-1, pp.249, 250, 256, 323, 331-43, 355, 359.

- 1 2 Christie's Photography Auction, London, May 1, 1996, Lot 213/Sale 558 Man Ray - Bridget Bate, 1941

- 1 2 Sotheby's New York, Auction catalogue: Photographs, Friday April 18, 1997, lot #249, Man Ray – Bridget Bate 1941.

- ↑ Descendants of Sir Francis Baring http://www.genealogics.org/descendtext.php?personID=I00021011&tree=LEO&display=block&generations=8

- ↑ "MISS BRIDGET BATE SETS WEDDING DAY", New York Times, October 10, 1939

- 1 2 3 4 Rara Avis - IMDb

- ↑ "Hugh Chisholms Jr. Have Son", New York Times, December 23, 1940

- ↑ Lundy, Darryl. "Bridget Bate Tichenor". The Peerage. The Peerage

- ↑ Chisholm Gallery Fine Sporting Art

- 1 2 Spring, Justin. "An interview with George Tooker," American Art v. 16, No. 1 (Spring 2002): pp. 61-81.

- 1 2 Hooks, Margaret. Surreal Eden-Edward James and Las Pozas, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007 ISBN 1-56898-612-2, ISBN 978-1-56898-612-8, p.57.

- 1 2 Gray, Francine du Plessix. Them: A Memoir of Parents, New York: The Penguin Group, 2006 ISBN 1-59420-049-1, p.307.

- 1 2 Leddick, David. Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein, and Their Circle, New York: Macmillan, 2001 ISBN 0-312-27127-1, ISBN 978-0-312-27127-5, pp.152-153.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Bridget Bate Tichenor Website

- ↑ The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume III, 1939-1944

- 1 2 Leddick, David. Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein, and Their Circle, New York: Macmillan, 2001 ISBN 0-312-27127-1, ISBN 978-0-312-27127-5, pp.201-202.

- ↑ A Journey Into Ancient Mystery Schools, by Zachary Selig, 2011, Scrbd.com

- ↑ Breton, André. "The Second Manifesto of Surrealism", Manifestos of Surrealism, Ann Arbor: U of Michigan Press, 1972, pp.117, 194.

- ↑ "Dream Works: Can a Legendary Surrealist Garden in Mexico Bloom Again?", New York Times Style Magazine, March 30, 2008

- ↑ www.cornermag.com - the Chronology of Remedios Varo

- ↑ Bridget Tichenor - IMDb

- ↑ Tufic Makhlouf - IMDb

- ↑ www.answers.com - rara avis

- ↑ FOBO: Brewer's: Rara Avis (Latin, a rare bird)

- ↑ Morelia Film Festival, Mexico

- ↑ Friedeberg, Pedro. (2011) De Vacaciones Por La Vida - Memorias no Autorizados del Pintor Pedro Friedeberg: Trilce Ediciones, Mexico DF, Mexico, Editor Deborah Holtz, Dirección General de Publicaciones del Conaculta y la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL) 2011, ISBN 978-607-455-503-5, ISBN 978-607-7663-24-9

- ↑ The Tarot Reader (Jean Patchett and Bridget Tichenor) - New York 1949 by Irving Penn SAAM

- ↑ María Félix: la Doña Auction

- ↑ Christie's Latin American Art Auction, New York, July 17-18, 2007, Bridget Tichenor Lot 182/Sale 1931 Domadora de quimeras

- ↑ Christie's Latin American Art Auction, New York, July 17-18, 2007, Bridget Tichenor Lot 181/Sale 1931 Caja de crystal

- ↑ History of Women Exposition 2008

- ↑ In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States at LACMA 2012 Archived February 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Art review: "In Wonderland: Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists" Los Angeles Times, January 30, 2012

- ↑ Secretería de Cultura DF: "Bridget Tichenor Presentación al público en general"

- ↑ "Reviven los sueños de Bridget Bate Tichenor" La Verdad de Temaulipas, April 28, 2012

External links

- Bridget Bate Tichenor at the Internet Movie Database

- Bridget Bate Chisholm Tichenor's Artist Page at Chisholm Gallery, LLC

- Lundy, Darryl. "Photo of Bridget Bate Tichenor by fashion photographer Francesco Scavullo, 1978". The Peerage. The Peerage website

- Lundy, Darryl. "Bridget Bate #159288". The Peerage. The Peerage website

- Morelia Film Festival, Mexico

- artnet: Bridget Tichenor, past auction results for Domadora de quimeras

- artnet: Bridget Tichenor, past auction results for Caja de cristal

- Bridget Bate Tichenor biography

- Royal Musings

- The First Biography of the Life of Bridget Bate Tichenor by Zachary Selig Scribd.com

- Bridget Bate Tichenor. Retrospective at Museo de la Ciudad de México Video