1st Airlanding Brigade (United Kingdom)

| 1st Airlanding Brigade Group 1st Airlanding Brigade | |

|---|---|

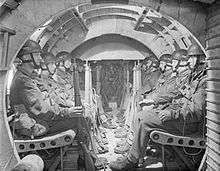

|

Men of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment, part of the 1st Airlanding Brigade, during the Battle of Arnhem, September 1944. | |

| Active | 1941–1945 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Airborne forces |

| Role | Glider infantry |

| Size | 4 battalions (maximum) |

| Part of | 1st Airborne Division |

| Engagements |

Sicily Landings Battle of Arnhem Operation Doomsday |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Brigadier Philip Hicks |

| Insignia | |

| Emblem of the British airborne forces |

|

The 1st Airlanding Brigade was an airborne infantry brigade of the British Army during the Second World War and the only glider infantry formation assigned to the 1st Airborne Division, serving alongside the 1st Parachute Brigade and 4th Parachute Brigade.

The brigade was formed in late 1941 during World War II through the conversion of an existing infantry brigade previously stationed in India, the 31st Independent Infantry Brigade. Two of the initial four infantry battalions left in May 1943 to form the new 6th Airlanding Brigade of the 6th Airborne Division and were replaced by a single new battalion, thereby reducing the brigade's strength by one quarter.

The brigade only saw action on two occasions during the Second World War, in Operation Ladbroke, as part of the Allied invasion of Sicily, in July 1943 and later in Operation Market Garden in September 1944. During the second operation, in the fighting around Arnhem, 1st Airlanding Brigade along with the rest of 1st Airborne Division held out against overwhelming German odds, sustaining very heavy losses. Only around 20 percent of the brigade were evacuated south of the River Rhine. The rest had either been killed, were missing or became prisoners of war.

Following the German surrender in mid-1945, 1st Airlanding Brigade were sent to Norway to disarm the German garrison. Later the same year the brigade was disbanded.

Formation

Under the command of Brigadier George F. Hopkinson, the 1st Airlanding Brigade Group was formed on 10 October 1941 through the re-designation of the 31st Independent Infantry Brigade, which had just returned to the United Kingdom after training for mountain warfare in British India.[1] Upon formation, the brigade consisted of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment (Borders), the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment (Staffords), the 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (OBLI), the 1st Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles (Ulsters) and supporting units.[2] These were the brigade's original infantry battalions and all remained part of its order of battle. Men in the battalions who were unsuitable for airborne service were weeded out and replaced by volunteers.[3]

The strength of the airlanding brigade almost equalled that of an airborne division's two parachute brigades.[4] To support the four infantry battalions, the brigade also had its own artillery, engineer and reconnaissance units until 1942, when they became divisional assets.[2] Another change that affected the brigade occurred in May 1943, when the Ulsters and the OBLI left to form the 6th Airlanding Brigade, of the 6th Airborne Division.[2][5] When the brigade returned to the United Kingdom, it was assigned the 7th Battalion, King's Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) in December 1943, a 2nd Line Territorial Army unit, which had until then been on home defence duties, stationed in the Orkney and Shetland islands.[6]

The brigade's glider infantry battalions consisted of 806 men in four rifle companies, each with four platoons along with a support company consisting of two Anti-tank platoons each with four 6 pounder guns, two mortar platoons armed with six 3 inch mortars, and two Vickers machine gun platoons.[7]

Transport for the brigade was normally the Airspeed Horsa glider, piloted by two men from the Glider Pilot Regiment.[8] With a wingspan of 88 feet (27 m) and a length of 67 feet (20 m), the Horsa had a maximum load capacity of 15,750 pounds (7,140 kg)—space for two pilots, a maximum of twenty-eight troops or two jeeps, one jeep and an artillery gun or one jeep with a trailer.[9][10] Sixty–two Horsa and one General Aircraft Hamilcar gliders were required to carry the airlanding battalion into action. The Hamilcar carried the battalion's two Universal Carriers used to support the mortar and machine-gun platoons.[7]

Operations

Sicily

The 1st Airborne Division, including the 1st Airlanding Brigade left England for North Africa in June 1943. The brigade now comprised only two battalions, the Borders and the Staffords, with Brigadier Philip "Pip" Hicks, in command, Brigadier Hopkinson having been promoted to major-general and given command of the 1st Airborne Division.[11] Once they arrived in theatre the brigade was based in the Oran area on the north-western Mediterranean coast of Algeria. Now part of the British Eighth Army training for the invasion of Sicily, code-named Operation Husky, started in earnest.[12]

Major-General Hopkinson had persuaded General Bernard Montgomery, commander of the Eighth Army, to include the 1st Airborne Division in the invasion of Sicily, against the wishes of both the commander of the British Airborne Forces, Major-General Frederick Browning and the commander of the Glider Pilot Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Chatterton. Both men were concerned that they had insufficient aircraft for the complete division to take part while British pilots and infantry were not familiar with the Waco CG-4 gliders that were to be used.[13] Their concerns proved correct as there were only enough aircraft for two of the division's four brigades to take part in the invasion. The 1st Parachute Brigade was assigned to Operation Fustian with orders to seize and hold the Primosole Bridge over the River Simeto. Prior to that, the 1st Airlanding Brigade was to take part in Operation Ladbroke, a glider assault on the Ponte Grande bridge across the Anapo river south of Syracuse. The brigade was to hold the bridge until relieved by the advance of the British 5th Infantry Division.[12][14] The 1st Airlanding Brigade was allocated 136 Waco and eight Airspeed Horsa gliders for the operation. Six of the Horsas carrying two infantry companies were scheduled to land at the bridge at 23:15 on 9 July in a coup-de-main operation.[15] The remainder of the brigade would arrive at 01:15 on 10 July using a number of landing-zones between 1.5 and 3 miles (2.4 and 4.8 km) away, then converge on the bridge to reinforce the defence.[14]

On 9 July, 2,075 men of the brigade along with seven jeeps, six artillery guns and ten mortars, boarded their gliders in Tunisia and took off at 18:00 bound for Sicily. En route they encountered strong winds, poor visibility and at times were subjected to anti-aircraft fire.[14] To avoid gunfire and searchlights, pilots of the towing aircraft climbed higher or took evasive action. In the confusion surrounding these manoeuvres, some gliders were released too early and 65 of them crashed into the sea, drowning around 252 men.[14] Of the remaining gliders only 12 landed at the correct landing-zones. Another 59 landed up to 25 miles (40 km) away while the remainder were either shot down or failed to release and returned to Tunisia.[16] Only one Horsa with a platoon of infantry from the Staffords landed near the bridge. Its commander Lieutenant Withers divided his men into two groups then swam across the river with half of them to take up positions on the opposite bank. Thereafter the bridge was captured following a simultaneous assault from both sides. The platoon then dismantled demolition charges that had been fitted to the bridge and dug in to wait for reinforcement or relief.[17] Another Horsa landed about 200 yards (180 m) from the bridge but exploded on landing, killing all on board. Three of the other Horsas carrying the coup-de-main party, landed within 2 miles (3.2 km) of the bridge—their occupants eventually finding their way to the site.[18] Reinforcements began to arrive at the bridge but by 06:30 they numbered only 87 men.[19]

Elsewhere, about 150 men landed at Cape Murro di Porco and captured a radio station. Based on a warning of imminent glider landings transmitted by the station's previous occupants, the local Italian commander ordered a counter-attack but his troops failed to get the message. The scattered nature of the landings now worked in the brigade's favour as they were able to cut all telephone wires in the immediate area.[17] Forces at the bridge came under repeated attacks from the Italians while the expected 5th Infantry Division relief did not appear at 10:00 as planned. By 15:30 only 15 of men at the bridge remained fit to fight and they were out of ammunition, as a result the Italians then recaptured the bridge. The first unit from 5th Infantry Division arrived at the bridge at 16:15 and mounted a successful counter-attack. The prior removal of demolition charges from the bridge had prevented the Italians from destroying it.[20] The 1st Airlanding Brigade then took no further part in the fighting and was withdrawn back to North Africa on 13 July.[21] During the landings in Sicily, the losses by 1st Airlanding Brigade were the worst of all the British units involved so far.[22] They amounted to 313 killed and 174 missing or wounded.[21] The accompanying glider pilots lost 14 killed moreover 87 were missing or wounded.[21]

Arnhem

After service in the Mediterranean the brigade returned to Woodhall Spa in Lincolnshire, where it was reinforced by the arrival of the 7th Battalion, King's Own Scottish Borderers in November 1943.[23] During the D-Day landings of 6 June 1944, the 1st Airlanding Brigade was part of the strategic reserve, on standby to deploy wherever they were needed to support the invasion.[24] The division and brigade were next assigned to Operation Market Garden at Arnhem in the Netherlands. This entailed three airborne divisions capturing bridges to be used subsequently by the British Second Army.[25] Prior to the operation, more than 15 planned airborne missions into France and Belgium had been cancelled due to the speed of the Allied advance.[26]

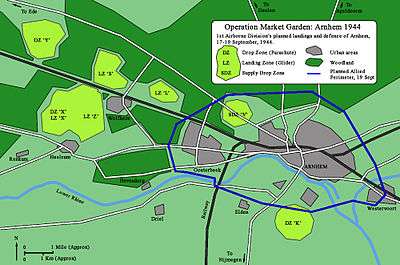

A shortage of transport aircraft meant that it would take three days to transport the division to Arnhem. The plan called for the majority of the 1st Airlanding Brigade and the 1st Parachute Brigade to land on day one. The parachute brigade would head for Arnhem and capture the bridges over the Lower Rhine while the airlanding brigade secured drop zones for units arriving on the second and third days.[27] When all the division's units had arrived the brigade would take up defensive positions to the west of Arnhem.[28] The 1st Airlanding Brigade units arriving on the second lift were to be two companies plus one mortar, one machine gun and one anti-tank platoon of the Staffords,[29] along with three platoons and sections from the mortar, machine gun and anti-tank platoons of the KOSB.[30] The Borders contingent amounted to a further eight platoons.[30][nb 1]

On 17 September 1944, the first lift successfully carried the majority of the brigade to Arnhem—only 12 gliders failed to arrive due to technical problems.[32][33] While the 1st Parachute Brigade headed for Arnhem the airlanding brigade dug in to secure the landing grounds. The Staffords dug in around landing zone 'S', the KOSB around drop zone 'Y' and the Borders around landing zone 'X'.[34] Also under command of the brigade, co-located with brigade headquarters at Wolfheze were the Glider pilots of No. 2 Wing, Glider Pilot Regiment, the equivalent of a small infantry battalion.[35]

On the night of 17–18 September, divisional commander Major-General Roy Urquhart was reported missing. Brigadier Hicks assumed command of the division[36] while Colonel Hilaro Barlow replaced Hicks as brigade commander.[37]

On day two, problems in Arnhem forced Hicks to change the divisional plan. Only the 2nd Parachute Battalion had reached the road bridge—strong German defences had halted the other battalions so Hicks decided that the Staffords would link up with the 1st Parachute Brigade in an attempt to reach their objective.[37] However, the Staffords also failed to break through the German defenders.[38] Bad weather over England kept the planned second lift on the ground. The first troops did not arrive until 15:00, a delay that gave the Germans time to approach the landing grounds and engage the KOSB in numerous probing attacks on the northern perimeter. At one stage KOSB commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Payton-Reid led a bayonet charge to clear the Germans from the area.[38] Meanwhile, the Borders were repeatedly attacked from the south of landing zone's 'X' and 'Z', and were eventually forced to call on the 75 mm guns of the 1st Airlanding Light Regiment to break up the attacks.[34] Hicks had previously decided to send the Staffords on the second lift to join their battalion fighting in Arnhem, while he also sent the 11th Parachute Battalion on the same lift to support 1st Parachute Brigade.[39] The KOSB, until then responsible for defending the landing ground, were attached to 4th Parachute Brigade to replace the 11th Parachute Battalion. However they were still responsible for defending landing ground 'L', for the arrival of the Poles gliders on day three. This left only the Borders, No. 2 Wing GPR and the field ambulance under brigade command.[40]

As day three dawned, the Staffords, and the 1st Parachute Battalion attacked at 04:00, their first objective being to link up with the 3rd Parachute Battalion trapped around St Elizabeth's Hospital. The attack failed but allowed Major-General Urquhart to rejoin the division from a position where he had been trapped by the Germans. This allowed Brigadier Hicks to resume command of the brigade,[41] whereupon Urquhart dispatched Colonel Barlow to take over command of 1st Parachute Brigade and co-ordinate the attack in Arnhem. He left in a jeep and was killed in a mortar barrage just outside Arnhem.[42] The 1st Airlanding Brigade, still holding landing zone 'L' for the expected Polish and resupply gliders, then came under attack from the west and north-west. During the night the KOSB had tried to take the high ground at Koepel, but were stopped by heavy machine gun fire and instead dug in.[43] The remainder of 4th Parachute Brigade advancing north of the railway line also encountered a strong German defence line and were unable to progress any further.[41] All three battalions were ordered to withdraw south of the railway line towards Wolfheze. Although the northern most battalion of the KOSB had thus far enjoyed a quiet morning, in the two hours it took them to advance south of the railway, two companies were now cut off and the entire battalion transport lost.[44] Still under fire from the pursuing Germans, the battalions crossed landing zone 'L' just as the third lift gliders were landing. While attempting to unload the gliders the Poles came under fire. Assuming the approaching men were Germans, they opened fire and caused some casualties.[45]

With no one in command, around 100 men, the remnants of the Staffords,[46] along with about 400 troops from the 1st Parachute Brigade, pulled back towards Oosterbeek. Here they were gathered together in an ad hoc formation known as the "Lonsdale Force" after Major Richard Lonsdale who was put in command. The Lonsdale Force deployed to the south-east of Oosterbeek to defend the division's artillery line.[47][48] Here, as dusk approached, Lance Serjeant John Baskeyfield of the Staffords, although wounded and with the rest of his men dead or wounded, engaged three tanks as they emerged from the woods with his anti-tank gun. He destroyed the first tank and disabled the second before his own weapon was destroyed. Moving to a nearby gun where the crew were already dead, he continued to fight the third tank alone. Shortly after he managed to disable it, he was killed a shell from a German tank. For his actions Baskeyfield received a posthumous Victoria Cross, the highest British military decoration.[49] The KOSB had by now arrived at the perimeter being formed around Oosterbeek and took up positions south of the railway line just north of division headquarters.[46]

By day four, the battalions of the 1st Airlanding Brigade were dispersed over a wide area. While the Borders were to the west on a line from the River Rhine east of Heveadorp to the Heelsum road, the remaining KOSB companies lay to the north with the remnants of the Staffords forming part of Lonsdale Force in the east. Brigade headquarters was established on open ground at the centre of the divisional area.[50] On day five (21 September), defence of the divisional area was divided between the two remaining brigade headquarters. The 1st Airlanding Brigade in the west now commanded the remaining three companies of Borders, the remnants of the KOSB, and what remained of the Royal Engineers, 21st Independent Company, Glider Pilots and Poles.[51] Lonsdale Force Major Robert Henry Cain of the Staffords disabled a tank with a PIAT and then, although wounded by machine gun fire, positioned one of the division's artillery guns and destroyed it. This was the first of a number of actions by Major Cain which led to the award of a Victoria Cross.[52] This second medal for the Staffords meant it became the only British battalion to receive two Victoria Crosses in one battle during the Second World War.[53]

The Germans did not mount an all-out infantry assault on the divisional area, which was under continuous mortar and artillery attack. Instead, each sector was subjected to small scale assaults at times supported by tanks or self-propelled guns. Enemy troops first attacked the Independent Company, then the Borders who were forced off the high ground overlooking the river, and finally the KOSB.[54][55] The Germans mounted a strong assault following the landing of the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade south of the river beside Driel. This attack forced the KOSB out of their positions, which were only regained after a bayonet charge. Fighting was so fierce that first reports suggested the KOSB had been annihilated,[56] although it turned out that the counter-attack had in fact reduced the battalion's strength to only 150 men.[57]

By day six, 22 September, the battle had settled into a routine of mortaring and small probing attacks at times supported by armoured vehicles and sniper fire. The Poles, dug in south of the river, relieved part of the pressure on the division, as some German forces were diverted to confront them.[58] The following day began in a similar way to previous days with a mortar and artillery bombardment, followed by infantry and armour trying to find a gap in the perimeter. The KOSB, Glider Pilots and the 21st Independent Company who were all defending the brigade area were repeatedly attacked.[59] Furthermore, food and water shortages also took their toll on the men, with foraging parties subjected to sniper fire.[60] On day eight, 24 September, although German attacks continued, the enemy were engaged by artillery of the XXX Corps south of the river and aircraft from the Royal Air Force. This broke up most assaults before they got started.[61]

On 25 September Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks, commander of XXX Corps, decided not to reinforce the position north of the Rhine and instead prepare for the evacuation of all survivors in Operation Berlin.[62] The evacuation took place on the night of 25–26 September.[63] Of the 2,526 men of 1st Airlanding Brigade that left England for Operation Market Garden, there were 230 killed, 476 evacuated and 1,822 were missing or prisoners of war.[31]

Norway

After Arnhem, replacements for the 1st Airlanding Brigade began to bring the brigade up to strength. Among the replacements was Brigadier Roger Bower who took the place of the injured Brigadier Hicks.[64] However, the Germans surrendered before they were involved in further action. The 1st Airborne Division including the airlanding brigade, the Special Air Service Brigade and an ad hoc brigade formed from the divisional artillery were sent to disarm the German occupation forces in Norway in May 1945. On entering Norway, the division would be responsible for maintaining law and order in the areas it occupied, ensuring that German units followed the terms of their surrender, securing and then protecting captured airfields, and finally preventing the sabotage of essential military and civilian structures.[65] After landing nearby, 1st Airlanding Brigade occupied the Norwegian capital Oslo, where Brigadier Bower became Commander, Oslo Area for the duration of the division's time in Norway. The city was chosen because as well as being the Norwegian capital it was also the centre of the Norwegian and German administration.[66] The brigade returned to the United Kingdom in August 1945, when the 1st Airborne Division was disbanded and the airlanding battalions returned to a conventional infantry role.[67]

Brigade composition

Commanding Officers

- Brigadier George F. Hopkinson

- Brigadier Philip Hugh Whitby Hicks

- Brigadier Roger Bower [11]

On formation 1941

- 1st Battalion, Border Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

- 1st Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles

- 1st Airlanding Reconnaissance Squadron, Royal Armoured Corps

- 9th Field Company (Airborne), Royal Engineers

- 223rd Anti-Tank Battery, Royal Artillery

- 458th Light Battery, Royal Artillery [2]

From December 1943

- 1st Battalion, Border Regiment

- 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment

- 7th (Galloway) Battalion, King's Own Scottish Borderers

- 181st Airlanding Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps [68]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ The headquarters of I Airborne Corps decided to use 38 gliders for the operation using, sufficient to lift the equivalent of 38 infantry platoons to Arnhem.[31]

- Citations

- ↑ Ferguson, p.6

- 1 2 3 4 "1 Airlanding Brigade subordinates". Order of Battle. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ↑ Blockwell and Clifton, p.63

- ↑ Guard, p.37

- ↑ "6 Airlanding Brigade subordinates". Order of Battle. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ↑ Blockwell and Clifton, p.58

- 1 2 Peters and Buist, p.55

- ↑ Tugwell, p.39

- ↑ Fowler, p.9

- ↑ Peters and Buist, p.9

- 1 2 "1 Airlanding Brigade Unit appointments". Order of Battle. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- 1 2 Ferguson, p.11

- ↑ Ferguson, p.10

- 1 2 3 4 Mitcham and Von Stauffenberg, p.73

- ↑ Tugwell, p.159

- ↑ Mitcham and Von Stauffenberg, pp.73–74

- 1 2 Mitcham and Von Stauffenberg, p.74

- ↑ Tugwell, p.160

- ↑ Mitcham and Von Stauffenberg, p.75

- ↑ Tugwell, p.161

- 1 2 3 Mitcham and Von Stauffenberg, p.78

- ↑ Tugwell, p.162

- ↑ Blockwell and Clifton, p.61

- ↑ Urquhart, p.16

- ↑ Urquhart, pp.1–3

- ↑ Peters and Buist, pp.18–28

- ↑ Urquhart, pp.5–10

- ↑ Tugwell, p.239

- ↑ Peters and Buist, p.328

- 1 2 Peters and Buist, pp.328–330

- 1 2 Nigl, p.75

- ↑ Peters and Buist, p.80

- ↑ Tugwell, p.244

- 1 2 Peters and Buist, p.127

- ↑ Peters and Buist, p.57

- ↑ Tugwell, p.258

- 1 2 Urquhart, p.61

- 1 2 Urquhart, p.72

- ↑ Urquhart, p.76

- ↑ Urquhart, p.60

- 1 2 Clark, p.170

- ↑ Middlebrook, p.211

- ↑ Urquhart, p.85

- ↑ Urquhart, p.91

- ↑ Clark, pp.170–171

- 1 2 Urquhart, p.101

- ↑ Clark, p.173

- ↑ Urquhart, p.95

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36807. pp. 5375–5376. 23 November 1944. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ↑ Urquhart, p.118

- ↑ Urquhart, p.121

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36774. pp. 5015–5016. 2 November 1944. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ↑ "The Staffordshire Regiment" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ↑ Clark, p.195

- ↑ Urquhart, p.124

- ↑ Urquhart, p.128

- ↑ Urquhart, p.127

- ↑ Urquhart, p.135

- ↑ Clark, p.220

- ↑ Clark, p.219

- ↑ Clark, p.224

- ↑ Clark, p.228

- ↑ Clark, pp.232–234

- ↑ "Bower, Sir Roger Herbert (1903–1990), Lieutenant General". Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives: King's College London. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ Otway, p.325

- ↑ Otway, pp.325–326

- ↑ Hickman, Mark. "1st Airlanding Brigade". Pegasus archive. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ Ferguson, p.15

Bibliography

- Blockwell, Albert; Clifton, Maggie (2005). Diary of a Red Devil: By Glider to Arnhem with the 7th King's Own Scottish Borderers. Solihill, United Kingdom: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 1-874622-13-2.

- Clark, Lloyd (2008). Arnhem: Jumping the Rhine 1944 and 1945. St Ives, United Kingdom: Headline Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7553-3637-1.

- Ferguson, Gregory (1984). The Paras 1940–84. Volume 1 of Elite series. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-573-1.

- Flint, Keith (2006). Airborne Armour: Tetrarch, Locust, Hamilcar and the 6th Airborne Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment 1938–1950. Solihull, United Kingdom: Helion & Company Ltd. ISBN 1-874622-37-X.

- Fowler, Will (2010). Pegasus Bridge — Benouville, D-Day 1944. Raid Series. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-848-0.

- Guard, Julie (2007). Airborne: World War II Paratroopers in Combat. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-196-6.

- Harclerode, Peter (2005). Wings Of War – Airborne Warfare 1918–1945. London. United Kingdom: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-304-36730-3.

- Lynch, Tim (2008). Silent Skies: Gliders At War 1939–1945. Barnsley, United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 0-7503-0633-5.

- Middlebrook, Martin (1994). Arnhem 1944: the Airborne Battle, 17–26 September. New York, New York: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-2498-X.

- Mitcham, Samuel W; Von Stauffenberg, Friedrich (2007). The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory. Stackpole Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3403-X.

- Moreman, Timothy Robert (2006). British Commandos 1940–46. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-986-X.

- Nigl, Alfred J (2007). Silent Wings Savage Death. Santa Ana, California: Graphic Publishers. ISBN 1-882824-31-8.

- Otway, Lieutenant-Colonel T.B.H (1990). The Second World War 1939–1945 Army Airborne Forces. London, United Kingdom: Imperial War Museum. ISBN 0-901627-57-7.

- Peters, Mike; Buist, Luuk (2009). Glider Pilots at Arnhem. Barnsley, United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 1-84415-763-6.

- Shortt, James; McBride, Angus (1981). The Special Air Service. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-396-8.

- Smith, Claude (1992). History of the Glider Pilot Regiment. London, United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Aviation. ISBN 1-84415-626-5.

- Tugwell, Maurice (1971). Airborne to Battle: A History of Airborne Warfare, 1918–1971. London, United Kingdom: Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0262-1.

- Urquhart, Robert (2007). Arnhem. Barnsley, United Kingdom: Pen and Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84415-537-8.