Waffle

| |

| Main ingredients | Batter or dough |

|---|---|

| Variations | Liège waffle, Brussels Waffle, Flemish Waffle, Bergische waffle, Stroopwafel and others |

|

| |

A waffle is a leavened batter or dough cooked between two plates, patterned to give a characteristic size, shape and surface impression. There are many variations based on the type of waffle iron and recipe used. Waffles are eaten throughout the world, particularly in Belgium, which has over a dozen regional varieties.[1]

Etymology

The word "waffle" first appears in the English language in 1725: "Waffles. Take flower, cream..."[2] It is directly derived from the Dutch wafel, which itself derives from the Middle Dutch wafele.[3]

While the Middle Dutch wafele is first attested to at the end of the 13th century, it is preceded by the French walfre in 1185; both are considered to share the same Frankish etymological root wafla.[4] Depending on the context of the use of wafla, it either means honeycomb or cake.[4][5]

Alternate spellings throughout modern and medieval Europe include waffe, wafre, wafer, wâfel, waufre, iauffe, gaufre, goffre, gauffre, wafe, waffel, wåfe, wāfel, wafe, vaffel, and våffla.[6][7]

History

Medieval origins

Waffles are preceded, in the early Middle Ages, around the period of the 9th–10th centuries, with the simultaneous emergence of fer à hosties / hostieijzers (communion wafer irons) and moule à oublies (wafer irons).[8][9] While the communion wafer irons typically depicted imagery of Jesus and his crucifixion, the moule à oublies featured more trivial Biblical scenes or simple, emblematic designs.[8] The format of the iron itself was almost always round and considerably larger than those used for communion.[10][11]

The oublie was, in its basic form, composed only of grain flour and water – just as was the communion wafer.[12] It took until the 11th century, as a product of The Crusades bringing new culinary ingredients to Western Europe, for flavorings such as orange blossom water to be added to the oublies; however, locally sourced honey and other flavorings may have already been in use before that time.[12][13]

Oublies, not formally named as such until ca. 1200, spread throughout northwestern continental Europe, eventually leading to the formation of the oublieurs guild in 1270.[14][15] These oublieurs/obloyers were responsible for not only producing the oublies but also for a number of other contemporaneous and subsequent pâtisseries légères (light pastries), including the waffles that were soon to arise.[15]

14th–16th centuries

In the late 14th century, the first known waffle recipe was penned in an anonymous manuscript, Le Ménagier de Paris, written by a husband as a set of instructions to his young wife.[16] While it technically contains four recipes, all are a variation of the first: Beat some eggs in a bowl, season with salt and add wine. Toss in some flour, and mix. Then fill, little by little, two irons at a time with as much of the paste as a slice of cheese is large. Then close the iron and cook both sides. If the dough does not detach easily from the iron, coat it first with a piece of cloth that has been soaked in oil or grease.[17] The other three variations explain how cheese is to be placed in between two layers of batter, grated and mixed in to the batter, or left out, along with the eggs.[18] However, this was a waffle / gaufre in name only, as the recipe contained no leavening.

Though some have speculated that waffle irons first appeared in the 13th–14th centuries, it was not until the 15th century that a true physical distinction between the oublie and the waffle began to evolve.[8] Notably, while a recipe like the fourth in Le Ménagier de Paris was only flour, salt and wine – indistinguishable from common oublie recipes of the time – what did emerge was a new shape to many of the irons being produced. Not only were the newly fashioned ones rectangular, taking the form of the fer à hosties, but some circular oublie irons were cut down to create rectangles.[8] It was also in this period that the waffle's classic grid motif appeared clearly in a French fer à oublie and a Belgian wafelijzer – albeit in a more shallowly engraved fashion – setting the stage for the more deeply gridded irons that were about to become commonplace throughout Belgium.[19][20]

By the 16th century, paintings by Joachim de Beuckelaer, Pieter Aertsen and Pieter Bruegel clearly depict the modern waffle form.[21] Bruegel's work, in particular, not only shows waffles being cooked, but fine detail of individual waffles. In those instances, the waffle pattern can be counted as a large 12x7 grid, with cleanly squared sides, suggesting the use of a fairly thin batter, akin to our contemporary Brussels waffles (Brusselse wafels).[22]

Earliest of the 16th century waffle recipes, Om ghode waffellen te backen – from the Dutch KANTL 15 manuscript (ca. 1500–1560) – is only the second known waffle recipe after the four variants described in Le Ménagier de Paris.[23] For the first time, partial measurements were given, sugar was used, and spices were added directly to the batter: Take grated white bread. Take with that the yolk of an egg and a spoonful of pot sugar or powdered sugar. Take with that half water and half wine, and ginger and cinnamon.[24]

Alternately attributed to the 16th and 17th centuries, Groote Wafelen from the Belgian Een Antwerps kookboek was published as the first recipe to use leavening (beer yeast): Take white flour, warm cream, fresh melted butter, yeast, and mix together until the flour is no longer visible. Then add ten or twelve egg yolks. Those who do not want them to be too expensive may also add the egg white and just milk. Put the resulting dough at the fireplace for four hours to let it rise better before baking it.[25] Until this time, no recipes contained leavening and could therefore be easily cooked in the thin moule à oublies. Groote Wafelen, in its use of leavening, was the genesis of contemporary waffles and validates the use of deeper irons (wafelijzers) depicted in the Beuckelaer and Bruegel paintings of the time.[22]

By the mid-16th century, there were signs of waffles' mounting French popularity. Francois I, king from 1494–1547, of whom it was said les aimait beacoup (loved them a lot), had a set of waffle irons cast in pure silver.[26][27] His successor, Charles IX enacted the first waffle legislation in 1560, in response to a series of quarrels and fights that had been breaking out between the oublieurs. They were required "d'être au moins à la distance de deux toises l'un de l'autre. " (to be no less than 4 yards from one to the other).[15]

17th–18th centuries

Moving into the 17th century, unsweetened or honey-sweetened waffles and oublies – often made of non-wheat grains – were the type generally accessible to the average citizen.[15][28] The wheat-based and particularly the sugar-sweetened varieties, while present throughout Europe, were prohibitively expensive for all but the monarchy and bourgeoisie.[15] Even for the Dutch, who controlled much of the mid-century sugar trade, a kilogram of sugar was worth ½ an ounce of silver (the equivalent of ~$7 for a 5 lb. bag, 01/2016 spot silver prices), while, elsewhere in Europe, it fetched twice the price of opium.[29][30] The wealthier families' waffles, known often as mestiers, were, "...smaller, thinner and above all more delicate, being composed of egg yolks, sugar, and the finest of the finest flour, mixed in white wine. One serves them at the table like dessert pastry."[15]

By the dawn of the 18th century, expansion of Caribbean plantations had cut sugar prices in half.[29] Waffle recipes abounded and were becoming decadent in their use of sugar and other rare ingredients.[31] For instance, Menon's gaufre from Nouveau Traité de la Cuisine included a livre of sugar for a demi-livre of flour.[32]

Germany became a leader in the development and publication of waffle recipes during the 18th century, introducing coffee waffles, the specific use of Hefeweizen beer yeast, cardamom, nutmeg, and a number of zuickerwaffeln (sugar waffles).[33][34] At the same time, the French introduced whipped egg whites to waffles, along with lemon zests, Spanish wine, and cloves.[35] Joseph Gillier even published the first chocolate waffle recipe, featuring three ounces of chocolate grated and mixed into the batter, before cooking.[36]

A number of the 18th century waffle recipes took on names to designate their country or region/city of origin – Schwedische Waffeln, Gauffres à l'Allemande and, most famous of all the 18th century varieties, Gauffres à la Flamande, which were first recorded in 1740.[36][37] These Gauffres à la Flamande (Flemish waffles / Gaufres de Lille) were the first French recipe to use beer yeast, but unlike the Dutch and German yeasted recipes that preceded them, use only egg whites and over a pound of butter in each batch.[37] They are also the oldest named recipe that survives in popular use to the present day, produced regionally and commercially by Meert.[38]

The 18th century is also when the word "waffle" first appeared in the English language, in a 1725 printing of Court Cookery by Robert Smith.[39] Recipes had begun to spread throughout England and America, though essentially all were patterned after established Dutch, Belgian, German, and French versions.[40] Waffle parties, known as 'wafel frolics', were documented as early as 1744 in New Jersey, and the Dutch had earlier established waffles in New Amsterdam (New York City).[41][42]

Liège waffles, the most popular contemporary Belgian waffle variety, are rumored to have been invented during the 18th century, as well, by the chef to the prince-bishop of Liège.[43][44] However, there are no German, French, Dutch, or Belgian cookbooks that contain references to them in this period – by any name – nor are there any waffle recipes that mention the Liège waffle's distinctive ingredients, brioche-based dough and pearl sugar.[45] It is not until 1814 that Antoine Beauvilliers publishes a recipe in l'Art du Cuisiner where brioche dough is introduced as the base of the waffle and sucre cassé (crushed block sugar) is used as a garnish for the waffles, though not worked into the dough.[46] Antonin Carême, the famous Parisian pastry chef, is the first to incorporate gros sucre into several waffle variations named in his 1822 work, Le Maitre d'Hotel Français.[47] Then, in 1834, Leblanc publishes a complete recipe for gaufres grêlées (hail waffles), where gros sucre is mixed in.[48] A full Gaufre de Liège recipe does not appear until 1921.[49]

19th–21st centuries

Waffles remained widely popular in Europe for the first half of the 19th century, despite the 1806 British Atlantic naval blockade that greatly inflated the price of sugar.[50] This coincided with the commercial production of beet sugar in continental Europe, which, in a matter of decades, had brought the price down to historical lows.[51] Within the transitional period from cane to beet sugar, Florian Dacher formalized a recipe for the Brussels Waffle, the predecessor to American "Belgian" waffles, recording the recipe in 1842/43.[52][53][54] Stroopwafels (Dutch syrup wafels), too, rose to prominence in the Netherlands by the middle of the century.[52] However, by the second half of the 1800s, inexpensive beet sugar became widely available, and a wide range of pastries, candies and chocolates were now accessible to the middle class, as never before; waffles' popularity declined rapidly.[50][51]

By the early 20th century, waffle recipes became rare in recipe books, and only 29 professional waffle craftsmen, the oublieurs, remained in Paris.[52][55] Waffles were shifting from a predominately street-vendor-based product to an increasingly homemade product, aided by the 1918 introduction of GE's first electric commercial waffle maker.[56] By the mid-1930s, dry pancake/waffle mix had been marketed by a number of companies, including Aunt Jemima, Bisquick, and a team of three brothers from San Jose, Calif. – the Dorsas. It is the Dorsas who would go on to innovate commercial production of frozen waffles, which they began selling under the name "Eggo" in 1953.[57]

Belgian-style waffles were showcased at Expo 58 in Brussels.[58] Another Belgian introduced Belgian-style waffles to the United States at the 1962 Seattle World's Fair, but only really took hold at the 1964 New York World's Fair, when another Belgian entrepreneur introduced his "Bel-Gem" waffles.[59] In practice, contemporary American "Belgian waffles" are actually a hybrid of pre-existing American waffle types and ingredients and some attributes of the Belgian model.

In the 21st century, waffles continue to evolve.[60] What began as flour and water heated between two iron plates are now popular the world over, produced in sweet and savory varieties, in myriad shapes and sizes.[61] Even as most of the original recipes have faded from use, a number of the 18th and 19th century varieties can still be easily found throughout Northern Europe, where they were first developed.[62]

Physical Composition

Waffle physical composition is a result of the interaction of ingredients to form structure and texture. Each ingredient has its own unique physical properties that when combined or heated, lead to various chemical reactions that turn liquid waffle batter into the golden brown crispy breakfast delight that is called an American waffle. A common waffle recipe is listed as follows:

1 ¾ cups of milk

2 eggs

½ cup of oil

2 cups of flour

1 tsp of baking soda

4 tsp baking powder

¼ tsp salt

½ teaspoon of vanilla extract

Each ingredient contributes to waffle texture and quality.[63]

Basic Overview of How a Waffle is Made

All these different properties come together to make a waffle a waffle. Milk provides the liquidity to the batter. When beaten, egg white can trap carbon dioxide gas bubbles to help the waffle stay fluffy. Another ingredient, oil, is a fat that contributes to a soft texture and helps prevent the escape of air bubbles. If air escaped too early, the waffle would become flat and lose its signature fluffiness. The flour is added to give the waffle its texture. Gluten (protein) in the flour provides the support matrix that traps air and supports the structure as the waffle rises. In addition to the flour, baking soda is added. Baking soda acts to release CO2 and is the main factor for the fluffiness of waffles. This equation sums up the reaction: 2NaHCO3 → Na2CO3 + CO2 + H2O. Baking soda also gives way to a base as seen in the equation, Na2CO3. This is where the next ingredient comes in, baking powder. Baking powder serves to neutralize the base that was formed when baking soda reacted chemically. Baking soda is bitter, and the powder that contains acidic ingredients help counteract that unwanted taste. The equation for baking powder is as follows: NaHCO3 + H+ → Na+ + H2O + CO2. Baking powder also produces CO2 gas bubbles to make the waffle light and airy. Next, salt is added to strengthen the soft mixes of fat and sugar. Lastly, vanilla extract is added for taste and overall flavor. The waffle batter is an oil in water mix of ingredients.[64]

Ingredients Explored

Milk:

Milk provides the liquid aspect of baking. It can hydrate proteins, starch, and leavening agents. Milk contains water, but it also contributes to browning because of its sugar which will be mentioned later on. In addition, milk fat adds flavor and texture. Water in the milk is absorbed and chemical changes take place that change the structure and texture of the food, in this case, the waffle. Moisture is important for the overall mouthfeel of the final baked product. Water vaporizes in the batter, and the steam that escapes will expand the cells and increase the waffle’s final volume and “puffiness”.[65] Water vapor also expands more than water as a liquid so it can act as a leavening agent as well. A leavening agent is a material that aids in the expansion of doughs and batters, and more leavening agents will be talked about later.[66]

Egg:

Eggs can be used in multiple ways in baked goods like waffles. Egg white (albumin) contains the protein lecithin. Lecithin coats air bubbles and prevents them from collapsing during the baking process. In this way, beaten eggs help give the waffle batter an airy texture. Lecithin can also serve another function as a binder that holds the cake or baked good together. In addition, eggs are used as an emulsifying ingredient or moistener. Lecithin acts as a releasing agent in waffles to prevent sticking, and it also improves color distribution on the waffle outer surface.[67] Lecitin interacts with oil and water to form an emulsion that promotes even blending of ingredients. An emulsion is a suspension of small droplets of a liquid in another liquid that cannot mix. Phospholipids are a major component of lecithin, and they have hydrophilic head groups with hydrophobic tails. The hydrophobic parts turn outside to interact with water and the hydrophilic parts are oriented inside to interact with the oil droplet.[68]

Oil:

Oil is fat. Fat has many practical applications in baked products. Fat can be a shortening, creaming, layering, and flavor agent in a wide variety of foods. Fat traps air during mixing to create small air bubbles trapped in fat droplets that later expand during baking and contribute to fluffiness. Fat also weakens the gluten network of the dough or batter and created a more tender product.

Oil also prevents the retrogradation of starches in the batter. Retrogradation is the realignment of amylose and amylopectin to reform a crystalline structure with the parallel chains. Retrogradation causes bread to stale and also causes waffles to stale. Starches that are dissolved in water form a gel which is favorable reaction. They lose their crystalline structure and therefore do not interfere with gluten formation.[69] Hydrophilic, water loving, lipid molecules slip between the two starched and prevent contact.[66] Flour: Starch is made up of simple sugars, and the protein in flour is called gluten. Gluten forms a cohesive mass that puffs up when it is baked and sets with an airy, light, consistency. It forms the structure of waffles, cakes, breads, and other baked goods. The net work of gluten consists of embedded starch granules. Flour quality depends on what type of wheat, the milling process, and what special treatments were used during the milling process. Different varieties of flour have more or less gluten. Usually, waffles contain less gluten than their other bread-like baked counterparts.[64] In recent years, gluten is becoming more and more unpopular due to various allergies and negative public opinion. The three types of gliadins called α-, γ- and ω-gliadin can contribute toward a gluten allergy called celiac disease.[70] Most gluten free products are crumbly and dry. Gas holding is more difficult so gums and stabilizers have to be added. Gelatin powder can be used as a binder in gluten free recipes. gluten free recipes include rice flour, sorghum, buckwheat, corn flour, etc.[71]

Baking soda:

Sodium bicarbonate releases CO2 when heated in the form of this equation:2NaHCO3 → Na2CO3 + H2O + CO2. Baking soda is cheap and easy to store, but along with CO2, it also produces sodium carbonate, an alkaline material. Sodium bicarbonate can give the waffle a bitter, soapy flavor and yellow coloring. Baking soda usually isn't used by itself because of this basic by product. Instead, it is mixed with acidic material like cream of tartar, honey, or golden syrup. If an imbalance of acidic and basic material is used, the pH could become affected and cause the whole waffle to come out undesirable. (Proteins at a non-optimal pH may denature, emulsions could be de-stabilized...etc) Baking powder is a commonly used acidic material used along with or instead of baking soda.[64]

Baking powder:

Baking powder is a mixture of NaHCO3 and a weak solid acid or acid salt. These salts usually are sodium aluminum sulfate or calcium phosphate. When baking powder dissolves in water in a raised temperature, CO2 is released. The equation is as follows: NaHCO3 + H+ (from the acid) → Na+ + H2O + CO2. Common acids found in baking powder are cream of tartar (potassium hydrogen tartrate), tartaric acid, sodium acid pyrophosphate, and acid calcium phosphate. Baking powder is used with baking soda to create less-basic by products that do not leave a bitter off-flavor in the waffle. In some formulas for baking powder, carbon dioxide is released as soon as it is dissolved in liquid and then more is released once it is heated during baking.[66] Baking powder is not only used in waffles but also in buns, fruit loaves, crumpets, pastries, cakes, pies, biscuits, omelets, and some cookies. Store also sell self raising flour which includes flour, baking soda, and an acid so the step of adding baking soda and baking powder can be skipped.[64]

Salt:

The addition of salt serves to enhance flavor and toughen the soft mixture of fat and sugar.[64] Salt is added in small quantities to add its own flavor and bring out the flavor in other ingredients. Salt strengthens the gluten and improves dough consistency. When the gluten matrix is stronger, the air bubbles (CO2) can be trapped more easily. Salt in larger quantities can also act as a preservative to bond water and lower the water activity so microbial growth is not optimal.[72]

Baking

Waffles are made using high moisture mix with medium gluten. Waffles are made from fluid batters with about a 1:1 ratio of milk to flour. Since waffles contain baking soda and baking powder, the batter should not be beaten or mixed extensively or else gas bubbles will form prematurely.[67] At high temperatures (baking temperatures) protein bonds can be broken and cause free amino acids to combine with other molecules present like sugar. Proteins are important for Maillard or non-enzymatic browning in foods because they combine with sugars in different ways to make certain aromatic flavor compounds. A more liquid batter can reduce starch swelling during the mixing process. Sugar granulation influences solubility in the batter and the final waffle texture.[66]

Maillard Browning

At high temperatures (baking temperatures) protein bonds can be broken and cause free amino acids to combine with other molecules present like sugar. Proteins are important for Maillard or non-enzymatic browning in foods because they combine with sugars in different ways to make certain aromatic flavor compounds. Browning provides the beneficial crunchy outer layer. The Maillard reaction is best in a basic environment so therefore, baking soda can greatly increase browning during the baking process. The first step in the Maillard reaction is the activation of reducing sugars by certain amino compounds like free amino acids or peptides.[73] Next, the activated sugars break down into 1,2- dicarbonyls or α-hydroxycarbonyls containing 2-4 carbons. The dicarbonyls undergo Strecker Degradation, a reaction that produces key flavors. Alkylpyrazines are produced.[74]

Browning contributes to more complex colors and flavors in the final product. Amino acids are deprotonated in a basic environment and can nucleophilically attack sugars. They lose their hydrogen atom off the carboxylic acid part. This causes there to be a negative charge on one oxygen atom that used its electrons to form a bond with a different atom. By adding baking soda, the food becomes more basic and allows Maillard browning to occur faster.[66] When baking powder is added (a mixture of basic bicarbonate ions and acidic ions), the acid and base components neutralize each other and do not affect the overall pH. The addition of more sugar can also increase browning. Dissolved sugar increases the surface tension and results in a more liquid batter. A more liquid batter can reduce starch swelling during the mixing process. Sugar granulation influences solubility in the batter and the final waffle texture.

Waffle Iron

An appliance called a waffle iron is used to cook waffles to the optimal golden brown coloring and crispness. The iron consists of an a plate with checker pattern divots that serve to hold the waffle batter when it is poured and create the waffle’s unique shape. Some waffle irons can prepare more than one waffle in the form of a double waffle maker that can be swiveled by hand 180 degrees. The stand sits on a supportive base.[75]

The grooves on the waffle iron that create the waffle’s famous ridges also serve another practical purpose. The ridges enhance the heat transfer and increase the heat path. With grooves, there is more surface area in contact with the waffle mix so it can be cooked in a timely manner. The pan is double sided for increased heat transfer so the waffle can be cooked from both sides to the middle instead of one side being burned to a crisp while the other side barely cooked. This way, the heat can reach the middle of the batter more quickly and cook the waffle faster.[75]

A Belgian style waffle iron is made of cast aluminum with a hollow interior on a support base connected to an electrical power source. The waffle batter is poured onto the waffle grid of the two plates, and then the top plate is closed to allow the the batter to cook. Some waffle makers may be turned 180 degrees while cooking. Waffle irons can be easily cleaned by just opening the casing where the waffle sits, letting the whole apparatus cool, and then wiping with a damp cloth. When cooking, the pan can be sprayed with Pam or cooking oil to provide lubricant and prevent sticking.[76]

Sticking During Baking

On the industrial scale, waffles are baked at 140–180 °C for 110 and 180 s, depending on thickness and batter type. Waffles should be fully baked and golden brown but not burnt. To decrease product loss, whether in the kitchen or in a factory, a waffle needs to be stable (not torn during take off). The ideal waffle should also have an even color throughout and not be crumbly. The perfect waffle is made of finely granulated wheat flour with low to medium protein content and low water adsorption capacity. The recommended pH value for waffle batter is from 6.1-6.5. High pH values can cause an increase in the browning reaction which causes an increase in the amount of batter residues on the waffle iron and therefore, more sticking.[77]

Waffle batter temperature should be in the range of 21 to 26.6 degrees Celsius.[77] If batter temperature is too high the batter forms clumps and sticks to the apparatus. Density and viscosity are also important aspects that have an effect on overall waffle quality. The recommended density of a waffle should be about 80–95 g/100 ml because it needs to be fluid enough to fill the whole plate of the waffle iron. Too stiff, and the dough’s spreadability decreases. Too much liquid, and the batter runs right off the plate. Viscosity is influenced by density (higher the density the higher the viscosity) but in the case of waffles, the effect of CO2 gas is more prevalent. The more aeration, the stiffer the waffle gets and the more viscous it is (it becomes foam-like). Aeration is the major factor that determines viscosity in a recipe so overall, the higher the aeration, the lower the density, and the higher the viscosity. Recipes vary for different types of waffles. Usually, better air-filled batters contribute to softer, fluffier waffles but viscosity should remain lower in order to have sufficient spreadability. Softer waffles do not have a correlation with sticking behavior. Density and viscosity do not have effect on sticking or adhering properties.[77]

Varieties

.jpg)

- Brussels waffles[78] are prepared with an egg-white-leavened or yeast-leavened batter, traditionally an ale yeast;[79] occasionally both types of leavening are used together. They are lighter, crisper and have larger pockets compared to other European waffle varieties, and are easy to differentiate from Liège Waffles by their rectangular sides. In Belgium, most waffles are served warm by street vendors and dusted with confectioner's sugar, though in tourist areas they might be topped with whipped cream, soft fruit or chocolate spread. Variants of the Brussels waffles – with whipped and folded egg whites cooked in large rectangular forms – date from the 18th century.[80] However, the oldest recognized reference to "Gaufres de Bruxelles" (Brussels Waffles) by name is attributed from 1842/43 to Florian Dacher, a Swiss baker in Ghent, Belgium, who had previously worked under pastry chefs in central Brussels.[81] Philippe Cauderlier would later publish Dacher's recipe in the 1874 edition of his recipe book "La Pâtisserie et la Confiture". Maximilien Consael, another Ghent chef, had claimed to have invented the waffles in 1839, though there's no written record of him either naming or selling the waffles until his participation in the 1856 Brussels Fair.[82][83] It should be noted that neither man created the recipe; they simply popularized and formalized an existing recipe as the Brussels waffle.[84]

- The Liège waffle[85] is a richer, denser, sweeter, and chewier waffle. Native to the greater Wallonia region of Eastern Belgium – and alternately known as gaufres de chasse (hunting waffles) – they're an adaptation of brioche bread dough, featuring chunks of pearl sugar which caramelize on the outside of the waffle when baked. It is the most common type of waffle available in Belgium and prepared in plain, vanilla and cinnamon varieties by street vendors across the nation.

- Flemish waffles, or Gaufres à la Flamande, are a specialty of northern France and portions of western Belgium.[86] The original recipe, published in 1740 by Louis-Auguste de Bourbon in Le Cuisinier Gascon, is as follows: Take "deux litrons" (1.7 liters or 7 cups) of flour and mix it in a bowl with salt and one ounce of brewer's yeast barm. Moisten it completely with warm milk. Then whisk fifteen egg whites and add that to the mixture, stirring continuously. Incorporate "un livre" (490 grams or 1.1 pounds) of fresh butter, and let the batter rise. Once the batter has risen, take your heated iron, made expressly for these waffles, and wrap some butter in a cloth and rub both sides of the iron with it. When the iron is completely heated, make your waffles, but do so gently for fear of burning them. Cooked, take them out, put them on a platter, and serve them with both sugar and orange blossom water on top.[87]

- American waffles[88] vary significantly. Generally denser and thinner than the Belgian waffle, they are often made from a batter leavened with baking powder, which is sometimes mixed with pecans, chocolate drops or berries and may be round, square, or rectangular in shape. Like American pancakes they are usually served as a sweet breakfast food, topped with butter and maple syrup, bacon, and other fruit syrups, honey, or powdered sugar. They are also found in many different savory dishes, such as fried chicken and waffles or topped with kidney stew.[89] They may also be served as desserts, topped with ice cream and various other toppings. A large chain (over 2,100 locations) of waffle specialty diners, Waffle House, is ubiquitous in the southern United States.

- Belgian waffles are a North American waffle variety, based on a simplified version of the Brussels waffle.[90] Recipes are typically baking soda leavened, though some are yeast-raised.[91] They are distinguished from standard American waffles by their use of 1 ½" depth irons.[92] Belgian waffles take their name from an oronym of the Bel-Gem brand, which was an authentic Brussels waffle vendor that helped popularize the thicker style at the 1964 New York World's Fair.[93]

- Bergische waffles, or Waffles from Berg county,[94] are a specialty of the German region of Bergisches Land. The waffles are crisp and less dense than Belgian waffles, always heart shaped, and served with cherries, cream and optionally rice pudding as part of the traditional afternoon feast on Sundays in the region.

- Hong Kong style waffle, in Hong Kong called a "grid cake" or "grid biscuits" (格仔餅), is a waffle usually made and sold by street hawkers and eaten warm on the street.[95] It is similar to a traditional waffle but larger, round in shape and divided into four quarters. It is usually served as a snack. Butter, peanut butter and sugar are spread on one side of the cooked waffle, and then it is folded into a semicircle to eat. Eggs, sugar and evaporated milk are used in the waffle recipes, giving them a sweet flavor. They are generally soft and not dense. Traditional Hong Kong style waffles are full of the flavor of yolk. Sometimes different flavors, such as chocolate and honey melon, are used in the recipe and create various colors. Another style of Hong Kong waffle is the eggette or gai daan jai (鷄蛋仔), which have a ball-shaped pattern.

- Pandan waffles originate from Vietnam and are characterized by the use of pandan flavoring and coconut milk in the batter.[96] The pandan flavoring results in the batter's distinctive spring green color.[97] When cooked, the waffle browns and crisps on the outside and stays green and chewy on the inside. Unlike most waffles, pandan waffles are typically eaten plain.

- Potato waffles are mainly found in the UK and Ireland, made from potato formed into a waffle iron shape.

- Scandinavian style waffles, common throughout the Nordic countries, are thin, made in a heart-shaped waffle iron. The batter is similar to other varieties. The most common style are sweet, with whipped or sour cream and strawberry or raspberry jam, or berries, or simply sugar, on top.

- In Norway, brunost and gomme (food) are also popular toppings. As with crèpes, there are those who prefer a salted style with various mixes, such as blue cheese.

- In Finland, savory toppings are uncommon; instead jam, sugar, whipped cream or vanilla ice cream are usually used.

- In Iceland, the traditional topping is either rhubarb or blueberry jam with whipped cream on top. Syrup and chocolate spread are also popular substitutes for the jam.

- The Swedish tradition dates at least to the 15th century, and there is even a particular day for the purpose, Våffeldagen (waffle day), which sounds like Vårfrudagen ("Our Lady's Day"), and is therefore used for the purpose. This is March 25 (nine months before Christmas), the Christian holiday of Annunciation.[98] They are usually topped with strawberry jam, bilberry jam, hjortron jam, raspberry jam, bilberry and raspberry jam, sugar and butter, vanilla ice cream and whipped cream. Other, savory, toppings include salmon roe, cold-smoked salmon and cream fraiche.

- Gofri (singular gofre) are waffles in Italy and can be found in the Piedmontese cuisine: they are light and crispy in texture, contain no egg or milk (according to the most ancient recipe)[99] and come both in sweet and savory versions.[100] Central Italian cuisine also features waffle-like cookies, which are locally known as pizzelle, ferratelle (in Abruzzo) or cancelle (in Molise).

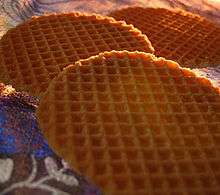

- Stroopwafels are thin waffles with a syrup filling. The stiff batter for the waffles is made from flour, butter, brown sugar, yeast, milk, and eggs. Medium-sized balls of batter are put on the waffle iron. When the waffle is baked and while it is still warm, it is cut into two halves. The warm filling, made from syrup is spread in between the waffle halves, which glues them together.[101] They are popular in the Netherlands and Belgium and sold in pre-prepared packages in shops and markets.

- Galettes campinoises / Kempense galetten are a type of waffle popular in Belgium. They are rigid and crunchy, but are buttery, crumbly and soft in the mouth.

- Hotdog waffles are long waffles with a hot dog cooked inside them, similar to a corn dog. Originating in Thailand, this snack is served with ketchup, mayonnaise, or both. The batter is similar to American waffles, but uses margarine instead of butter, as it is one of the more accepted eccentricities of their food culture.[102]

- Waffles on a stick are long waffles cooked onto a stick, resembling an ice pop. Also known as Lolly Waffles It is again very similar to American-style waffles, but has a special Iron used. These waffles are usually dipped in something like chocolate syrup, and with sprinkles on top.[103]

Toppings

Waffles can be eaten plain (especially the thinner kinds) or eaten with various toppings, such as:

- butter

- chocolate chips

- apple butter

- dulce de leche

- fruits:

- honey

- jam or jelly

- chocolate spread

- peanut butter

- syrup:

- whipped cream

- powdered sugar

Ice cream cones are also a type of waffles or wafers.

Shelf Stability and Staling

Mixing is a critical step in batter preparation since over mixing causes the gluten to develop excessively and create a batter with too high of a viscosity that is difficult to pour and does not expand easily. A thick batter that is difficult spreading in the baking iron has an increased water activity of around 0.85. The increased viscosity made it harder for water to evaporate from the waffle causing an increase in water activity. The control waffles with a softer texture had a water activity of 0.74 after cooking. The Aw is less because the softer texture allows the water to evaporate. With an increased storage time, waffle physical and textural properties changes regardless of the batter viscosity.[104] Aged waffles shrink becuase air bubbles leak out and the structure starts to condense. Hardness and viscosity also increases as time goes by. Aged waffle samples displayed a starch retrogradation peak that increased with storage time due to the fact that more crystalline structures were present. Starch retrogradation is mentioned previously in this paper. The enthalpy value for melting of starch crystals increased with storage time as well.[104]

See also

References

- ↑ "Les Gaufres Belges". Gaufresbelges.com. Retrieved on 2013-04-07.

- ↑ Robert Smith (1725). Court Cookery.

- ↑ "Waffle", The Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary

- 1 2 "Gaufre", Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales

- ↑ Larousse Gastronomique. Crown Publishing Group. 2001. p. 1285. ISBN 978-0-609-60971-2.

- ↑ fr:Gaufre (cuisine)

- ↑ "Bulletin de la Société liégeoise de littérature wallonne, Volumes 34-35". Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Les Moules à Oublies", Gilles Soubigou, Conservateur du Patrimoine, Monuments Historiques – Lorraine

- ↑ "De historie van wafels en wafelijzers", Nederlands Bakkerijmuseum

- ↑ "fer à hosties", 13e siècle, Conservation des antiquités et objets d'art de Charente-Maritime – Ministère de la Culture (France), PM17000403

- ↑ "fer à oublies ", Gourmet Museum and Library, Hermalle-sous-Huy, Belgium

- 1 2 Gil Marks (2010). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Wiley. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-470-94354-0.

- ↑ Jean Liebault, La maison rustique, 1582, cité dans Raymond Lecoq, Les Objets de la vie domestique. Ustensiles en fer de la cuisine et du foyer des origines au XIX siècle, Berger-Levrault, 1979, p. 180.

- ↑ "Oublie", Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Adolphe Chéruel (1865). Dictionnaire historique des institutions: mœurs et coutumes de la France. L. Hachette et cie. p. 243.

- ↑ "LE MENAGIER DE PARIS", Michael Delahoyde, Washington State University

- ↑ "Gauffres iiii manières", circa 1392–1394, anonymous author, Paris, B.N.F. fr. 12477, fol. 171 r

- ↑ "Gauffres iiii manières ", translation by Janet Hinson, David D. Friedman

- ↑ "Wafelijzer, Brugge, 1430", Gruuthusemuseum / Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage

- ↑ "Gaufrier de Girard le Pâtissier", Un Fer à Gaufres du Quinzieme siècle, H. Henry, Besançon, France

- ↑ "Gemüseverkäuferin", Pieter Aertsen, 1567, Stiftung preussischer Kulturbesitz – Staatliche Museen, Berlin

- 1 2 "Het gevecht tussen Carnaval en Vasten", Pieter Bruegel (the elder), 1569

- ↑ " Gent KANTL 15, volume 1", Christianne Muusers (translator), Coquinaria

- ↑ "Om ghode waffellen te backen", Christianne Muusers (translator), Coquinaria

- ↑ André Delcart (2007). "Groote Wafelen". Winterfeesten en gebak. Maklu. p. 38. ISBN 978-90-8575-009-3.

- ↑ Adolphe Chéruel (1865). Dictionnaire historique des institutions, moeurs et coutumes de la France, 1. Libr. de L. Hachette. p. 477.

- ↑ Les Français peints par eux-mêmes: encyclopédie morale du 19e siècle. Curmer. 1841. p. 220.

- ↑ Maurice Laporte (1571). Les épithètes. p. 112.

- 1 2 "The Price of Sugar in the Atlantic, 1550–1787", Figure I, Klas Rönnbäck, Europ. Rev. Econ. Hist., 2009

- ↑ "Recipes | In Season", July: Rhubarb, Gourmet Magazine, Gourmet Traveller, Adelaide Lucas

- ↑ Johann Nikolaus Martius (1719). Unterricht von der wunderbaren Magie und derselben medicinischen Gebrauch. Nicolai. p. 164.

- ↑ Menon (1739). Nouveau traité de la Cuisine, Volume 1. p. 334.

- ↑ Johanna Katharina Morgenstern-Schulze (1785). Unterricht für ein junges Frauenzimmer, das Küche und Haushaltung selbst besorgen will, Volume 1. p. 310.

- ↑ Stettinisches Kochbuch für junge Frauen, Haushälterinnen und Köchinnen: Nebst einem Anhange von Haus- und Wirtschaftsregeln. Keffke. p. 371.

- ↑ "Gaufres", Les Dons de Comus, T. 3, p. 131, 1758

- 1 2 "Gauffre", Le Cannameliste français, p. 111, 1751.

- 1 2 Beatrice Fink (1995). Les Liaisons savoureuses: réflexions et pratiques culinaires au XVIIIe siècle. Université de Saint-Etienne. p. 159. ISBN 978-2-86272-070-8.

- ↑ "Meert, Depuis 1761". Meert.fr. Retrieved on 2013-04-07.

- ↑ Robert Smith (cook.) (1725). Court cookery: or, The compleat English cook. p. 1.

- ↑ Robert Smith (cook.) (1725). Court cookery: or, The compleat English cook. p. 176. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ John Austin Stevens; Benjamin Franklin DeCosta; Henry Phelps Johnston, Volume 2, Issue 2; Martha Joanna Lamb; Nathan Gilbert Pond (1878). The Magazine of American history with notes and queries. A. S. Barnes. p. 442.

- ↑ M.J. Stephey (23 November 2009) "Waffles", TIME Magazine.

- ↑ Bart Biesemans (16 July 2011) "Luikse wafel verdringt Brusselse wafel", De Standaard.

- ↑ "Waffles", visitBelgium.com

- ↑ "The history of the "Gaufre de Liège"", gofre.eu

- ↑ Antoine B. Beauvilliers (1814). L'art du cuisinier ... Pilet.

- ↑ Marie Antonin Carême (1822). Le Maitre d'hotell français: ou parallèle de la cuisine ancienne et moderne ... Didot. p. 33.

- ↑ Leblanc (pastry cook.) (1834). Manuel du pâtissier: ou, Traité complet et simplifié de la pâtisserie de ménage, de boutique et d'hôtel ... Librairie encyclopédique de Roret. p. 200.

- ↑ André Delcart (2007). Winterfeesten en gebak. Maklu. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-8575-009-3.

- 1 2 "From extreme luxury to everyday commodity", Sugar in Sweden, 17th to 20th centuries, pp. 8–9, Klas Rönnbäck, Göteborg Papers in Economic History, No. 11. November 2007

- 1 2 "Sweet Diversity: Overseas Trade and Gains from Variety after 1492", Jonathan Hersh, Hans-Joachim Voth, Real Sugar Prices and Sugar Consumption Per Capita in England, 1600–1850, p.42

- 1 2 3 "Wafels", Henk Werk , http://home.hccnet.nl/h.werk/Wafels.htm

- ↑ "Jaargang 25 inclusief het boek "Brusselse Wafels"", Academie voor de Streekgebonden Gastronomie

- ↑ "Brusselse Wafels", Philippe Cauderlier, 1874

- ↑ "OUBLIEUR", Les métiers d'autrefois, genealogie.com

- ↑ William George (2003). Antique Electric Waffle Irons 1900–1960: A History of the Appliance Industry in 20th Century America. Trafford Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-55395-632-7.

- ↑ Sherri Liberman (2011). American Food by the Decades. ABC-CLIO. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-313-37698-6.

- ↑ "Marollenwijk smult van Brusselse wafels", Leen Dewitte, De Standaard, standard.be, maandag 03 maart 2008

- ↑ "Bel-Gem Waffles", Bill Cotter

- ↑ "Gaufres: Vanille, Ispahan, Pietra", Pierre Herme, pierreherme.com

- ↑ "Search: Waffles", tastespotting.com

- ↑ "Confrérie de la Gaufre Liégeoise", Liége waffle fraternity, Belgium

- ↑ "Waffles I Recipe". Allrecipes. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Chemistry of Baking" (PDF). VI-Food-D-Baking: 1–8.

- ↑ Lauterbach, Sharon; Albrecht, Julie (1994). "NF94-186 Functions of Baking Ingredients". Agriculture Digital Commons.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Claire, Jillian. "The Chemistry of Baking". Scholar Commons: University of South Carolina: 1–93.

- 1 2 Huber, Regina; Schoenlechner, Regine (2016-09-01). "Waffle production: influence of batter ingredients on sticking of waffles at baking plates—Part II: effect of fat, leavening agent, and water". Food Science & Nutrition: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1002/fsn3.425. ISSN 2048-7177.

- ↑ "Lecithin Overview" (PDF). ADM. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ↑ Carman, George. 2016. Lecture Slides: Carbohydrates

- ↑ Jr, Richard J. Coppedge; Charles, Cathy (2008-09-17). Gluten-Free Baking with The Culinary Institute of America: 150 Flavorful Recipes from the World's Premier Culinary College. Adams Media. ISBN 1598696130.

- ↑ Hamaker, B. R. (2007-11-08). Technology of Functional Cereal Products. Elsevier. ISBN 9781845693886.

- ↑ Bakeinfo. "Ingredients and their uses- BakeInfo (Baking Industry Research Trust)". www.bakeinfo.co.nz. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ↑ Ashoor, S. H.; Zent, J. B. (1984-07-01). "Maillard Browning of Common Amino Acids and Sugars". Journal of Food Science. 49 (4): 1206–1207. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1984.tb10432.x. ISSN 1750-3841.

- ↑ Ajandouz, El Hassan; Puigserver, Antoine (1999-05-01). "Nonenzymatic Browning Reaction of Essential Amino Acids: Effect of pH on Caramelization and Maillard Reaction Kinetics". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 47 (5): 1786–1793. doi:10.1021/jf980928z. ISSN 0021-8561.

- 1 2 Andrizzi, Sheldon (Oct 9, 1984), Easily cleaned and serviced waffle iron, retrieved 2016-11-27

- ↑ Weigle, Barbara (Nov 6, 1990), Appliance for preparing two waffles, retrieved 2016-11-27

- 1 2 3 Huber, Regina; Schoenlechner, Regine (2016-09-01). "Waffle production: influence of batter ingredients on sticking of fresh egg waffles at baking plates—Part I: effect of starch and sugar components". Food Science & Nutrition: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1002/fsn3.424. ISSN 2048-7177.

- ↑ "Brussels Waffle Recipe", Adam Wayda, 2016-01-15

- ↑ "Een nieuwe, royale oud-Belgische hoofdstedelijke wafel?", faro | tijdschrift over cultureel erfgoed, Belgium (in Dutch), pp 14–21, 03/03/2008

- ↑ "le de brusselier", "Petite histoire de la cuisine"

- ↑ "Om te backen, dicke wafelen". deswaene.be. Retrieved on 2013-04-07.

- ↑ Henk Werk (22 February 2012). Wafels. Home.hccnet.nl. Retrieved on 2013-04-07.

- ↑ Lonely Planet Encounter Guide Brussels, Bruges, Antwerp & Ghent 1st edition, 2008, p. 151

- ↑ waffle-recipes.com (1 June 2015). Brusselse Wafels: Dacher's and Consael's Recipes .

- ↑ http://www.waffle-recipes.com/liege-waffle-recipe-gaufres-de-liege/ ["Liège Waffle Recipe"], Adam Wayda, 2014-03-13

- ↑ M. Bounie (2003/2004) La Gaufre Flamande Fourrée, Polytech'Lille-Département IAA, p 6.

- ↑ Beatrice Fink (1995). Les Liaisons savoureuses: réflexions et pratiques culinaires au XVIIIe siècle. Université de Saint-Etienne. p. 159. ISBN 978-2-86272-070-8.

- ↑ "American waffle recipe". Lonestar.texas.net. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford: Oxford University press. pp. xx + 892. ISBN 978-0192806819.

- ↑ "His waffles made memories at the Queens World's Fair". Newsday. 1989-08-22.

- ↑ http://www.foodnetwork.com/search/search-results.html?searchTerm=belgian+waffle&form=global&_charset_=UTF-8 ["Belgian Waffle Recipes"], Food Network

- ↑ http://www.nemcofoodequip.com/products/waffle-cone-bakers/belgian-waffle-bakers ["Nemco Belgian Waffle Irons"], Nemco

- ↑ Roberts, Sam (2008-07-27). "A Fair, a Law and the Urban Walker". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ↑ "Bergish Waffle recipe" (in German). Remscheid, Germany: Bergisches-wiki.de. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ "Descriptions of Hong Kong Waffles". Mrnaomi.wordpress.com. 2008-01-23. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ Katharine Shilcutt (July 2, 2011). "100 Favorite Dishes: No. 81, Pandan Waffles at Parisian Bakery III". Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Pandan Waffles Banh Kep La Dua". January 15, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ Waffle Day in Sweden, notice from Radio Sweden

- ↑ "I gofri" (in Italian). Turin, Italy: Gofreria Piemonteisa - Torino. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- ↑ I gofri

- ↑ Stroopwafels. Traditional delicacys. Retrieved on 2008-01-02

- ↑ http://luckypeach.com/recipes/waffle-hot-dog/

- ↑ https://lollywaffle.com/lollywaffle

- 1 2 Sozer, Nesli; Kokini, Jozeph (2009). COMBAT RATION NETWORK FOR TECHNOLOGY IMPLEMENTATION. THE CENTER FOR ADVANCED FOOD TECHNOLOGY: DEFENSE LOGISTICS AGENCY.

External links

-

The dictionary definition of waffle at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of waffle at Wiktionary -

Media related to Waffles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Waffles at Wikimedia Commons - Waffle recipes in the Cookbook wikibook