Buck Rogers

| Buck Rogers | |

|---|---|

|

Poster for Buck Rogers serial, 1939 | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Amazing Stories |

| First appearance | August 1928 |

| Created by | Philip Francis Nowlan |

| In-story information | |

| Full name | Anthony "Buck" Rogers |

| Partnerships |

Wilma Deering Dr. Elias Huer |

Buck Rogers is a fictional space opera character created by Philip Francis Nowlan in the novella, Armageddon 2419 A.D., and subsequently appearing in multiple media. In Armageddon 2419 A.D., published in the August 1928 issue of the pulp magazine, Amazing Stories, the character's given name was "Anthony".[1] A sequel, The Airlords of Han, was published in the March 1929 issue.

Philip Nowlan and the syndicate John F. Dille Company, later known as the National Newspaper Syndicate, were contracted to adapt the story into a comic strip. After Nowlan and Dille enlisted editorial cartoonist Dick Calkins as the illustrator, Nowlan adapted the first episode from Armageddon 2419, A.D. and changed the hero's name from "Anthony" to "Buck". The strip made its first newspaper appearance on January 7, 1929.[1] Later adaptations included a film serial, a television series (in which his first name was changed from "Anthony" to "William"), and other formats.

The adventures of Buck Rogers in comic strips, movies, radio and television became an important part of American popular culture. This popular phenomenon paralleled the development of space technology in the 20th century and introduced Americans to outer space as a familiar environment for swashbuckling adventure.[1][2]

Buck Rogers has been credited with bringing into popular media the concept of space exploration,[3] following in the footsteps of literary pioneers such as Jules Verne, H. G. Wells and Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Characters and story

The character first appeared as Anthony Rogers, the central character of Nowlan's Armageddon 2419 A.D. Born in 1898, Rogers is a veteran of the Great War (World War I) and by 1927 is working for the American Radioactive Gas Corporation investigating reports of unusual phenomena reported in abandoned coal mines near Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania. On December 15, there is a cave-in while he is in one of the lower levels of a mine. Exposed to radioactive gas, Rogers falls into "a state of suspended animation, free from the ravages of catabolic processes, and without any apparent effect on physical or mental faculties". Rogers remains in suspended animation for 492 years.

Rogers awakens in 2419. Thinking that he has been asleep for just several hours, he wanders for a few days in unfamiliar forests (what had been Pennsylvania almost five centuries before). He notices someone clad in strange clothes, who is under attack. He defends the person, Wilma Deering, killing one of the attackers and scaring off the rest. On "air patrol", Deering was attacked by an enemy gang, the Bad Bloods, presumed to have allied themselves with the Hans.

Wilma takes Rogers to her camp, where he meets the bosses of her gang. He is invited to stay with them or leave and visit other gangs. They hope that Rogers' experience and knowledge he gained fighting in the First World War may be useful in their struggle with the Hans who rule North America from 15 great cities they established across the continent. They ignored the Americans who were left to fend for themselves in the forests and mountains as their advanced technology prevented the need for slave labor.

In the sequel, The Airlords of Han, six months have passed and the hunter is now the hunted. Rogers is now a gang leader and his forces, as well as the other American gangs, have surrounded the cities and are attacking constantly. The airlords are determined to use their fleet of airships to break the siege.

In 1933, Nowlan and Calkins co-wrote Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, a novella that retold the origin of Buck Rogers and also summarized some of his adventures. A reprint of this work was included with the first edition of the novel Buck Rogers: A Life in the Future (1995) by Martin Caidin.

In the 1960s, Nowlan's two novellas were combined by editor Donald A. Wollheim into one paperback novel, Armageddon 2419 A.D. The original 40-cent edition featured a cover by Ed Emshwiller.

Comic strip

The story of Anthony Rogers in Amazing Stories caught the attention of John F. Dille, president of the National Newspaper Service syndicate, and he arranged for Nowlan to turn it into a strip for syndication. The character was given the nickname Buck, and some have suggested that Dille coined that name based on the 1920s cowboy actor, Buck Jones.[4]

On January 7, 1929, the Buck Rogers in the 25th Century A.D. comic strip debuted. Coincidentally, this was also the date that the Tarzan comic strip began. The first three frames of the series set the scene for Buck's "leap" 500 years into Earth's future:

- I was 20 years old when they stopped the world war and mustered me out of the air service. I got a job surveying the lower levels of an abandoned mine near Pittsburgh, in which the atmosphere had a peculiar pungent tang and the crumbling rock glowed strangely. I was examining it when suddenly the roof behind me caved in and...

Buck is rendered unconscious, and a strange gas preserves him in a suspended animation or coma state. He awakens and emerges from the mine in 2429 A.D., in the midst of another war.[1]

After rescuing Wilma, he proves his identity by showing her his American Legion button. She then explains how the Mongol Reds emerged from the Gobi desert to conquer Asia and Europe and then attacked America starting with that "big idol holding a torch". Using their disintegrator beams, they easily defeated the army and navy and wiped out Washington, D.C. in three hours. As the people fled the cities, the Mongols built new cities on the ruins of the major cities. The Mongols left the Americans to fend for themselves as their advanced technology prevented the need for slave labor. The scattered Americans formed loosely bound organizations or "orgs" to begin to fight back.

Wilma takes Buck back to the Alleghany org in what was once Philadelphia. The leaders don't believe his story at first but after undergoing electro-hypnotic tests, they believe him and admit him into their group.[5]

On March 30, 1930, a Sunday strip joined the Buck Rogers daily strip. There was, as yet, no established convention for the same character having different adventures in the Sunday strip and the daily strip (many newspapers carried one but not the other), so the Sunday strip at first followed the adventures of Buck's young friend Buddy Deering, Wilma Deering's younger brother, and Buddy's girlfriend Alura, later joined by Black Barney. It was some time before Buck made his first appearance in a Sunday strip. Other prominent characters in the strip included Buck's friend Dr. Huer, who punctuated his speech with the exclamation, "Heh!"; the villainous Killer Kane and his paramour Ardala; and Black Barney, who began as a space pirate but later became Buck's friend and ally.[1] In addition, Buck and his friends encountered various alien races. Hostile species Buck met included the Tiger Men of Mars, the dwarf-like Asterites of the Asteroid belt, and giant robots called Mekkanos.[2]

Like many popular comic strips of the day, Buck Rogers was reprinted in Big Little Books; illustrated text adaptations of the daily strip stories; and in a Buck Rogers pop-up book.[1]

Nowlan is credited with the idea of serializing Buck Rogers, based on his novel Armageddon 2419 and its Amazing Stories sequels. Nowlan approached John Dille, who saw the opportunity to serialize the stories as a newspaper comic strip. Dick Calkins, an advertising artist, drew the earliest daily strips, and Russell Keaton drew the earliest Sunday strips. The author of Buck Rogers told the inventor R. Buckminster Fuller in 1930 that "he frequently used [Fuller's] concepts for his cartoons".[6]

Keaton wanted to switch to drawing another strip written by Calkins, Skyroads, so the syndicate advertised for an assistant and hired Rick Yager in 1932. Yager had formal art training at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts and was a talented watercolor artist; all the strips were done in ink and watercolor. Yager also had connections with the Chicago newspaper industry, since his father, Charles Montross Yager, was the publisher of The Modern Miller; Rick Yager was at one time employed to write the "Auntie's Advice" column for his father's newspaper. Yager quickly moved from inker and writer of the Buck Rogers "sub-strip" (early Sunday strips had a small sub-strip running below) to writer and artist of the Sunday strip and eventually the daily strips.

Authorship of early strips is extremely difficult to ascertain. The signatures at the bottoms of the strips are not accurate indicators of authorship; Calkins' signature appears long after his involvement ended, and few of the other artists signed the artwork, while many pages are unsigned. Yager probably had complete control of Buck Rogers Sunday strips from about 1940 on, with Len Dworkins joining later as assistant. Dick Locher was also an assistant in the 1950s. For all of its reference to modern technology, the strip itself was produced in an old-fashioned manner—all strips began as India ink drawings on Strathmore paper, and a smaller duplicate (sometimes redrawn by hand) was hand-colored with watercolors. Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, has an extensive collection of original artwork. The strip's artists also worked on a variety of tie-in promotions such as comic books, toys and model rockets.

The relations between the artists of the strip (Yager et al.) and the owners of the strip (the Syndicate) became acrimonious, and in mid-1958, the artists quit.[7] Murphy Anderson was a temporary replacement, but he did not stay long. George Tuska began drawing the strip in 1959 and remained until the final installment of the original comic strip, which was published on July 8, 1967.

Revived in 1979 by Gray Morrow and Jim Lawrence, the strip was retitled Buck Rogers in the 25th Century in 1980. Long-time comic book writer Cary Bates signed on in 1981, continuing until the strip's 1983 finale.

Buck Rogers was popular enough to inspire other newspaper syndicates to launch their own science fiction strips.[8] The most famous of these imitators was Flash Gordon (1934-2003);[9] others included Jack Swift (1930-1937), Brick Bradford (1933-1987), Don Dixon and the Hidden Empire (1935-1941),[10] Speed Spaulding (1940-1941),[8] and John Carter of Mars (1941-1943).[11]

Radio

In 1932, the Buck Rogers radio program, notable as the first science-fiction program on radio, hit the airwaves. It was broadcast in four separate runs with varying schedules. Initially broadcast as a 15-minute show on CBS in 1932, it was on a Monday through Thursday schedule. In 1936, it moved to a Monday, Wednesday, Friday schedule and went off the air the same year. Mutual brought the show back and broadcast it three days a week from April to July 1939 and from May to July 1940, a 30-minute version was broadcast on Saturdays. From September 1946 to March 1947, Mutual aired a 15-minute version on weekdays.[1][12]

The radio show again related the story of our hero Buck finding himself in the 25th century. Actors Matt Crowley, Curtis Arnall, Carl Frank and John Larkin all voiced him at various times. The beautiful and strong-willed Wilma Deering was portrayed by Adele Ronson, and the brilliant scientist-inventor Dr. Huer was played by Edgar Stehli.

The radio series was produced and directed by Carlo De Angelo and later by Jack Johnstone.

Film and television adaptations

World's Fair

A ten-minute Buck Rogers film premiered at the 1933–1934 World's Fair in Chicago. John Dille Jr. (son of strip baron John F. Dille) starred in the film, which was called Buck Rogers in the 25th Century: An Interplanetary Battle with the Tiger Men of Mars. A 35mm print of the film was discovered by the filmmaker's granddaughter, donated to UCLA's film and television archive, restruck and subsequently posted to the web. It is now available on the VCI Entertainment DVD 70th Anniversary release. It was later shown in department stores to promote Buck Rogers merchandise. It was shot in the Action Film Company studio in Chicago, Illinois, directed by Dr. Harlan Tarbell. The characters included Buck Rogers, Wilma Deering, Dr. Huer, Killer Kane, Ardala, King Grallo of the Martian Tiger Men, and robots.[13]

Movie serial

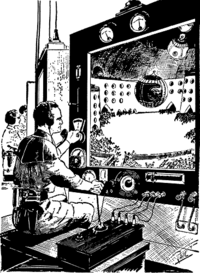

A 12-part Buck Rogers serial film was produced in 1939 by Universal Pictures Company. Buck Rogers (Buster Crabbe) and his young friend Buddy Wade get caught in a blizzard and are forced to crash their airship in the Arctic wastes. In order to survive until they can be rescued, they inhale their supply of Nirvano gas which puts them in a state of suspended animation. When they are eventually rescued by scientists, they learn that 500 years have passed. It is now 2440. A tyrannical dictator named Killer Kane and his henchmen now run the world. Buck and Buddy must now save the world, and they do so with the help of Lieutenant Wilma Deering and Prince Tallen of Saturn.

The serial had a small budget and saved money on special effects by reusing material from other stories: background shots from the futuristic musical Just Imagine (1930), as the city of the future, the garishly stenciled walls from the Azura palace set in Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars, as Kane's penthouse suite, and even the studded leather belt that Crabbe wore in Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars turned up as part of Buck's uniform. Between 1953 and the mid-1970s, this film serial was edited into three distinct feature film versions.[1]

1950–1951 ABC television series

The first version of Buck Rogers to appear on television debuted on ABC on April 15, 1950 and ran until January 30, 1951. There were a total of 36 black and white episodes in all (allowing for a 2-month summer hiatus).[1][14] Unfortunately, no episodes of the show survive today.

Its time slot initially was on Saturdays at 6 p.m., and each episode was 30 minutes. The program was later rescheduled to Tuesday at 7 p.m., where it ran against the popular Texaco Star Theatre hosted by Milton Berle. The show was sponsored by Peter Paul candy bars.

The producers were trying to emulate the success of DuMont's Captain Video, but the series probably failed as a result of its minuscule budget. The decision to put the show on a summer hiatus for almost two months also undercut efforts to build an audience.[1][15]

The storyline was very faithful to Philip Francis Nowlan's original novel Armageddon 2419 AD, although in the 1950 TV series, Buck Rogers finds himself in the year 2430. Based in a secret lab in a cave behind Niagara Falls (the city of Niagara was now the capital of the world), Buck battles intergalactic troublemakers.[16] Due to the minuscule budget, most of the episodes took place mainly in the secret lab.

There were a number of changes to the cast during the series' short duration. Three actors played Buck Rogers in the series: Earl Hammond (who starred as Buck very briefly), Kem Dibbs (whose last appearance in the role was aired on June 3rd), and Robert Pastene (whose first appearance in the role was aired on June 10th). The show apparently went on summer hiatus from around July 7th until the end of August, probably reappearing on the air again around Labor Day with Robert Pastene still in the lead role. (Kem Dibbs went on to have a long acting career in film and television.)

Two actresses portrayed Wilma Deering: Eva Marie Saint and Lou Prentis. Two actors would also play Dr. Huer: Harry Southern and Sanford Bickart. Black Barney Wade was played by Harry Kingston.

The series was directed by Babette Henry, written by Gene Wyckoff and produced by Joe Cates and Babette Henry. The series was broadcast live from station WENR-TV, the ABC affiliate in Chicago. There are no known surviving kinescopes of this first Buck Rogers television series.

Motion picture and 1979–1981 NBC television series

In 1979, Buck Rogers was revived and updated for a prime-time television series for NBC Television. The pilot film was released to cinemas on March 30, 1979. Good box office returns led NBC to commission a full series, which started in September 1979. Glen A. Larson produced the film and the first season of the eventual series.[1]

The series starred Gil Gerard as Captain William "Buck" Rogers, a United States Air Force and NASA pilot who commands Ranger III, a space shuttle-like ship that is launched in 1987. When his ship flies through a space phenomenon containing a combination of gases, his ship's life support systems malfunction and he is frozen and left drifting in space for 504 years. By the time he is revived, he finds himself in the 25th century. There, he learns that Earth was united following a devastating global nuclear war that occurred in the late 20th century, and is now under the protection of the Earth Defense Directorate, headquartered in New Chicago. The latest threat to Earth comes from the spaceborne armies of the planet Draconia, which is planning an invasion.

Co-starring in the series were Erin Gray as crack Starfighter pilot Colonel Wilma Deering, and Tim O'Connor as Dr. Elias Huer, head of Earth Defense Directorate, and a former starpilot himself. Ardala appeared (played by Pamela Hensley), as a Draconian princess supervising her father's armies, with Kane (played by Henry Silva in the film; by Michael Ansara in the series) as her enforcer, a gender reversal of the original characters where Ardala was Killer Kane's sidekick. Although Black Barney did not appear as a character in the series, there was a character named Barney Smith (played by James Sloyan) who appeared in the two-part episode, "The Plot to Kill a City". New characters added for the series included a comical robot named Twiki (played by Felix Silla and voiced by Mel Blanc), who becomes Buck's personal assistant, and Dr. Theopolis (voiced by Eric Server), a sentient computer that Twiki often carries around.

The series ran for two seasons on NBC. Production and broadcast of the second season was delayed by several months due to the 1980 actors strike. When the series returned in early 1981, its core format had been revised. Now rather than defending Earth, Buck and Wilma were aboard the deep-space exploration vessel Searcher on a mission to track down the lost colonies of humanity. Tim O'Connor's Dr. Huer was written out of the series and replaced by Wilfrid Hyde-White as quirky scientist Dr. Goodfellow and Broadway character actor Jay Garner as Vice Admiral Efram Asimov of the Earth Force. Also onboard was Thom Christopher playing the role of Hawk, a stoic birdman in search of other members of his ancient race. The revamp was unsuccessful and the series was canceled at the end of the 1980–1981 season.

Two novels based on the series by Addison E. Steele were published, a novelization of the 1979 feature film, and That Man on Beta, an adaptation of an unproduced teleplay.

Future films

Frank Miller was slated to write and direct a new motion picture with Odd Lot Entertainment, the production company that worked with Miller on The Spirit.[17][18] However, after The Spirit became a box office and critical failure, Miller's involvement with the project ended.[19]

Role-playing games and video games

Buck Rogers XXVC

In 1988, TSR, Inc. created a game setting based on Buck Rogers, called Buck Rogers XXVC. Many products were produced that were set in this universe, including comic books, novels, role-playing game material and video games. In the role-playing game, the player characters were allied to Buck Rogers and NEO (the New Earth Organisation) in their fight against RAM (a Russian-American corporation based on Mars). The games also extensively featured "gennies" (genetically enhanced organisms). The gameplay of the Buck Rogers - Battle for the 25th Century board game by TSR dealt with token movement and resource management. There is purported to be a single expansion for the board game called the Martian Wars Expansion, but it is not known if this was ever released.

Books

From 1990 to 1991, ten "comics modules" set in the Buck Rogers XXVC universe were published, entitled Rude Awakening #1 - #3, Black Barney #1 - #3. and Martian Wars #1-#4. These shared the numbering as a series issues #1 - #10 with issue #10 as a flip-book with Intruder #10. There has been speculation that two more stories were printed but not widely distributed.

Ten paperback novels set in the XXVC universe were published, starting in 1989:

- Arrival (anthology) by Flint Dille, Abigail Irvine, Melinda Seabrooke (M.S.) Murdock, Jerry Oltion, Ulrike O'Reilly and Robert Sheckley (TSR, Mar 1989, ISBN 0-88038-582-0)

The Martian Wars Trilogy

- Rebellion 2456 by M.S. Murdock (TSR, May 1989, ISBN 0-88038-728-9)

- Hammer of Mars by M.S. Murdock (TSR, Aug 1989, ISBN 0-88038-751-3)

- Armageddon off Vesta by M.S. Murdock (TSR, Oct 1989, ISBN 0-88038-761-0)

The Inner Planets Trilogy

- First Power Play by John Miller (TSR, Aug 1990, ISBN 0-88038-840-4)

- Prime Squared by M.S. Murdock (TSR, Oct 1990, ISBN 0-88038-863-3)

- Matrix Cubed by Britton Bloom (TSR, May 1991, ISBN 0-88038-885-4)

Invaders of Charon Trilogy

- The Genesis Web by Ellen C. & Theodore M. Brennan (C.M. Brennan) (TSR, May 1992, ISBN 1-56076-093-1)

- Nomads of the Sky by William H. Keith, Jr. (TSR, Oct 1992, ISBN 1-56076-098-2)

- Warlords of Jupiter by William H. Keith, Jr. (TSR, Feb 1993, ISBN 1-56076-576-3)

Also based on the game

- Buck Rogers: A Life in the Future by Martin Caidin, a standalone novel retelling the original story. (TSR, 1995, ISBN 0-7869-0144-6)

Pinball

At the beginning of 1980, a few months after the show debuted, Gottlieb came out with a Buck Rogers pinball machine to commemorate the resurgence of the franchise.

Video games

In 1990, Strategic Simulations, Inc. released a Buck Rogers XXVC video game, Countdown to Doomsday, for the Commodore 64, IBM PC, Sega Mega Drive, and other platforms. It released a sequel, Matrix Cubed, in 1992.

High-Adventure Cliffhangers

In 1995, TSR created a new and unrelated Buck Rogers role-playing game called High-Adventure Cliffhangers. This was a return to the themes of the original Buck Rogers comic strips. This game included biplanes and interracial warfare, as opposed to the space combat of the earlier game. There were only a few expansion modules created for High-Adventure Cliffhangers. Shortly afterward, the game was discontinued, and the production of Buck Rogers RPGs and games came to an end. This game was neither widely advertised nor very popular. There were only two published products: the box set, and "War Against the Han".

Planet of Zoom video game

Sega released the arcade video game Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom (Japanese: バック・ロジャース:プラネット・オブ・ズーム Hepburn: Bakku Rojāsu: Puranetto obu Zūmu) in 1982. It was a forward-scrolling rail shooter where the user controls a spaceship in a behind-the-back third-person perspective that must destroy enemy ships and avoid obstacles;[20] the game was notable for its fast pseudo-3D scaling and detailed sprites.[21] The game would later go on to influence the 1985 Sega hit Space Harrier, which in turn influenced the 1993 Nintendo hit Star Fox.[22] In Japan, the game was known as Zoom 909 (Japanese: ズーム909 Hepburn: Zūmu kyū-maru-kyū), a title shared by the smooth conversion of the game for the Sega SG-1000 console.[23]

Buck is never seen in the game, except assumedly in the illustration on the side of the arcade cabinet, and its only real connections to Buck Rogers are the use of the name and the outer space setting. Home versions were released for the Atari 2600, Atari 5200, Atari XE, ColecoVision, Coleco Adam, Intellivision, MSX and Sega SG-1000 video game systems, and the Commodore VIC-20, Commodore 64, Texas Instruments TI-99/4A, Apple II and ZX Spectrum computers. A version for IBM PC using CGA graphics was also available.[20][24][25][26]

Later novels

Authorized sequels to Armageddon 2419 A.D. were written in the 1980s by other authors working from an outline co-written by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle and loosely tied-in with their bestseller Lucifer's Hammer (1977). The first sequel begins c. 2476 A.D., when a widowed and cantankerous 86-year-old Anthony Rogers is mysteriously rejuvenated during a resurgence of the presumed-extinct Han, now called the Pr'lan. The novels include:

- Mordred by John Eric Holmes (Ace, January 1981, ISBN 0-441-54220-4)

- Warrior's Blood by Richard S. McEnroe (Ace, January 1981, ISBN 0-441-87333-2)

- Warrior's World by Richard S. McEnroe (Ace, October 1981, ISBN 0-441-87338-3)

- Rogers' Rangers by John Silbersack (Ace, August 1983, ISBN 0-441-73380-8)

Toys

The first Buck Rogers toys appeared in 1933, four years after the newspaper strip debuted and a year after the radio show first aired. Some mark this as the beginning of modern character based licensed merchandising, in that not only was character's name and image were branded on many unrelated products but also on many items of merchandise unique to or directly inspired by that character. Of the many toys associated with Buck Rogers, none is more closely identified with the franchise than the eponymous toy rayguns.

The first "Buck Rogers gun" wasn't technically a raygun, although its futuristic shape and distinctive lines set the pattern for all "space guns" that would follow. The XZ-31 Rocket Pistol, a 9½-inch pop gun that produced a distinctive "zap!" sound, was at the American Toy Fair in February 1934. Retailed for 50¢, which was by no means inexpensive during the Great Depression, it was designed to mimic the rocket pistols seen in the comic strips from their inception. In the comics, they were automatic pistols that fired explosive rockets instead of bullets, each round as effective as a 20th-century hand grenade.[27]

The XZ-31 Rocket Pistol, was the first of six toy guns manufactured over the next two decades by Daisy, which had an exclusive contract with John Dille, then head of the National Newspaper Syndicate of America, for all Buck Rogers toys. Most of these were pop guns, which had the virtue a being noisemakers that couldn't fire any actual projectiles and were thus guaranteed to be harmless as one of their selling points.[28]

The XZ-35 Rocket Pistol, a smaller 7-inch version without some of the detail of the original that's often called "the Wilma Pistol" by collectors, followed in 1935, retailing for 25¢ and arguably offering less value for quintuple the initial price. Most consumers hardly noticed, because in 1935 the floodgates were opened and they had a lot choices. Both the XZ-31 and XZ-35 were cast in "blued" steel with silvery nickel accents.

The XZ-38 Disintegrator Pistol, the first actual "ray gun" toy and such an iconic symbol of the franchise that it made a cameo appearance in the first episode of the 1939 movie serial, as if to show that what the audience was seeing was indeed the Real Thing, debuted in 1935. It was a 10-inch pop gun topped with flint-and-striker sparkler using a mechanism not unlike that used in cigarette lighters, cast in a distinctive metallic copper color.

The XZ-44 Liquid Helium Water Pistol was produced in late 1935 and early 1936. Loaded like a syringe by dipping nozzle into a container of water and drawing back a plunger, it was advertised to be capable of shooting 50 times without reloading.

In 1946, following World War II and the advent of the atomic bomb, Daisy reissued the XZ-38 in a silver finish that mimicked the new jet aircraft of the day as the U-235 Atomic Pistol. By then, pop guns were considered old-fashioned, and even the Buck Rogers franchise was losing its luster, having been overtaken by real-world events and the prospect of actual manned space flight.

By 1952, Daisy lost its exclusive license to the Buck Rogers name and even dropped any pretense of making a toy raygun. Its final offering was a reissue of the XZ-35 with a garish red, white, blue and yellow color scheme, dubbed the Zooka. The Buck Rogers rocket pistol that had started it all 20 years earlier had been overtaken by the real world bazooka.

"Space guns" in general and "rayguns" in particular only gained in prestige as the Cold War "space race" began and interest in "The Buck Rogers Stuff" was renewed, but it was no longer enough to offer a futuristic cap or pop gun. A proper raygun needed to actually project some sort of ray if it were to capture the imaginations of would-be space travelers of 1950s Americans. Enter the era of the plastic battery-powered flashlight raygun.

In 1953, Norton-Honer introduced the Sonic Ray Gun, which was essentially a 7½-inch flashlight mounted on a pistol grip. Pressing the trigger activated not only the flashlight beam (which had interchangeable colored lenses for differently colored "rays") but also an electronic buzzer. It could therefore be used as a pretend raygun but also as an actual Morse Code signal device.

This toy, and its successor, the Norton-Honer Super Sonic Ray Gun, was featured prominently in the actual Buck Rogers newspaper strips of the time, many of which concluded with a secret message in a Morse Code variant called the Rocket Rangers International Code, the key to which was available only by sending as self-addressed stamped envelope to the newspaper syndicate or the "cheat sheet" included in the package with the toy.

In 1934, a Rocket Police Patrol Ship windup red and green tin toy spaceship was produced by Louis Marx & Company with Buck seated in the cockpit holding a ray gun rifle. A second orange and yellow Patrol Ship was released the same year by Marx with window profile portraits of both Wilma and Buddy Deering on the right side and Buck and Dr Huer on the left side. Both tin toys are in the collection of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

In 1936, a line of Buck Rogers painted lead metal toy soldier three-inch figures were made for the British market. These were a set of six British Premium figures for Cream of Wheat and included Buck, Dr. Huer, Wilma, Kane, Ardala and an unidentified Mekkano Man Robot.

In 1937, Tootsietoys put out a six-piece die cast metal set of four 5″ long space ships and two 1.75″ tall figures of Buck and Wilma.

In 2009 and 2011, two versions of Buck Rogers action figures were released by the entertainment/toy companies "Go Hero" and "Zica Toys". The first is a vintage version of Buck Rogers as he appeared in the original comic strip. This 1:6 scale figure of Buck wears the 1930s period uniform including visor leather like plastic helmet and vest, a glass bubble space helmet, a red light up plastic flame jet pack, a mini gold colored metal XZ-38 Disintegrator Ray Pistol and a wooden slotted lid box with the limited edition number up to 1000. The second 1:9 scale figure is based on Gil Gerard wearing the white flight suit from the 1979 movie/TV series and also features a Tigerman figure.

Comic books

Over the years, there have been many Buck Rogers appearances in comics as well as his own series. Buck appeared in 69 issues of the 1930s comic Famous Funnies, then 2 appearances in Vicks Comics, both published by Eastern Color Printing. Then in 1940 Buck got his own comic entitled Buck Rogers which lasted for six issues, again published by Eastern Printing.

In 1933, Whitman (an imprint of Western Publishing) produced 12 Buck Rogers adventure comics. Kelloggs Cereal Company produced two Buck Rogers giveaway comics, one in 1933 and again in 1935. In 1951, Toby Press released 3 issues of Buck Rogers, all reprints of the comic strip. In 1955, an Australian company called Atlas Productions produced 5 issues of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.

Gold Key Comics published a single issue of a Buck Rogers comic in 1964.[29]

A second series was based on the 1979 television series and was published from 1979 to 1982, first by Gold Key,[30] then by Whitman Publishing,[31] continuing the numbering from the 1964 single issue.

TRS, Inc. published a 10-issue series based on their Buck Rogers XXVC game from 1990 to 1991.[32]

In 2009, Dynamite Entertainment began a monthly comic book version of Buck Rogers[33][34] by writer Scott Beatty[35] and artist Carlos Rafael.[36] The first issue was released in May 2009. The series ran 13 issues (#0-12) plus an annual, later collected into 2 trade paperbacks.

In 2012, Hermes Press announced a new comic book series with artwork by Howard Chaykin. The series was collected into a graphic novel titled Howard Chaykin's Buck Rogers Volume 1: Grievous Angels in 2014.[37]

Web series

The Cawley Entertainment Company in 2009 announced it would produce a web series, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century in association with the Dille Family Trust.[38][39] The series was purported to be based on the original comic strip and shows how Rogers is propelled from World War One into the 25th century. It was to star Bobby Quinn Rice[40] in the title role of Lucas "Buck" Rogers. Gil Gerard and Erin Gray, who played Rogers and Deering in the 1979 movie and television series, were set to appear in the first episode as Buck Rogers' parents, and Samantha Gray Hissong[41] (daughter of Erin Gray) to play Madison Gale. A teaser scene with Gerard and Gray was released on YouTube in May 2010[42]

Announced for webcasting on the Internet in 2010, the series never materialized and all references to it on the Internet Movie Database have been deleted. A May 4, 2011 article purported that the project was "dead", citing comments from Gerard and Gray.[43] A Kickstarter crowd-sourced funding effort failed to reach its goal,[44] and no official word as to the status of the project from the producers has been released since the Kickstarter effort.

Influence on language and popular culture

Buck Rogers' name has become proverbial in such expressions as "Buck Rogers outfit" for a protective suit that looks like a space suit. For many years, all the general American public knew about science fiction was what they read in the funny papers, and their opinion of science fiction was formed accordingly.[3][45] Another phrase in common use before 1950 was for deriding science fiction fans about "that crazy Buck Rogers stuff".[46]

Such was the fame of Buck Rogers that this became the basis for one of the most fondly remembered science fiction spoofs in a series of cartoons in which Daffy Duck portrayed Duck Dodgers. The first of these was Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century (1953), which was directed by Chuck Jones. There were also two sequels to this cartoon, and ultimately a Duck Dodgers television series.

Buck Rogers comic strip is featured in Steven Spielberg's blockbuster sci-fi movie E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982). E.T. is inspired to create a makeshift communicating device (to 'phone home') by copying Buck Rogers.

The Buck Rogers appellation has become a particular descriptive term for vertical landings of spaceships, which was the predominant mode of rocket landing envisioned in the pre-spaceflight era at the time Buck Rogers made his original appearance. While many science fiction authors and other depictions in popular culture showed rockets landing vertically, typically resting after landing on the space vehicle's fins, Buck Rogers seems to have gained a special place as a descriptive compound adjective. For example, this view was sufficiently ingrained in popular culture that in 1993, following a successful low-altitude test flight of a prototype rocket, a writer opined: "The DC-X launched vertically, hovered in mid-air ... The spacecraft stopped mid-air again and, as the engines throttled back, began its successful vertical landing. Just like Buck Rogers."[47] In the 2010s, SpaceX rockets have likewise seen the appellation to Buck Rogers in a "Quest to Create a 'Buck Rogers' Reusable Rocket."[48] or a Buck Rogers dream.[49]

The animated television series Futurama, created by Matt Groening and David X. Cohen in 1999, was strongly influenced by themes and characters from the "Buck Rogers" comic strip, as well as many other science fiction books and films.

"Buck Rogers" was a hit single by British rock band Feeder in 2001.

The Foo Fighters' self-titled album (1995) features Buck Rogers' XZ-38 Disintegrator Pistol on the album's cover.

Track nine of Hyphy Bay Area rapper Mac Dre's album Heart of a Gangsta, Mind of a Hustla, Tongue of a Pimp (2000) is titled "Black Buck Rogers".

In The Right Stuff (1983), the film about the United States supersonic test pilots of the 1940s and 1950s and the early days of the United States space program, in one scene, the character of the air force Liaison Man tells test pilots Chuck Yeager and Jack Ridley and test pilots and future Mercury Seven astronauts Gus Grissom, Deke Slayton and Gordon Cooper about the need for positive media coverage in order to assure continued government funding for the rocket program, dramatically declaring "no bucks - no Buck Rogers!" In a later scene in which the seven astronauts confront the NASA rocket scientists who have been running the program to demand changes to allow them to fly their spacecraft as actual pilots rather than as mere passive passengers in vehicles totally controlled from the ground—threatening to reveal to the press how they were being marginalized despite their public status as heroes, which would in turn damage Congressional support for the program—Cooper, Grissom and Slayton repeat the "no bucks - no Buck Rogers!" speech to the startled scientists to make their point.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Garyn G. Roberts, "Buck Rogers", in Ray B. Browne and Pat Browne (.ed) The Guide To United States Popular Culture. Bowling Green, OH : Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 2001. ISBN 0879728213 (p.120)

- 1 2 Robert Jennings,"Bucking the Future: From 1928 to the 25th Century With Anthony Rogers". Comic Buyer's Guide July 5, 1990. (pp. 58, 60, 62, 65-66).

- 1 2 Patrick Lucanio, Gary Coville, Smokin' Rockets: The Romance of Technology in American Film, Radio and Television, 1945–1962 (2002). McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1233-X

- ↑ "Buck Rogers in the 25th Century AD". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on 2008-08-14. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- ↑ Rolandanderson.se

- ↑ Fuller, R. Buckminster, Critical Path, ISBN 978-0-3121-7488-0, Chap.8, p.262

- ↑ Time, June 30, 1958.

- 1 2 Ron Goulart, "The 30s -- Boomtime for SF Heroes". Starlog magazine, January 1981 (pp. 31–35).

- ↑ Maurice Horn (editor) 100 Years of American Newspaper Comics (Gramercy Books: New York, Avenel, 1996) ISBN 0-517-12447-5. Flash Gordon entry by Bill Crouch, Jr., (p. 118)

- ↑ Peter Poplaski, "Introduction" to Flash Gordon Volume One: Mongo, the Planet of Doom by Alex Raymond, edited by Al Williamson. Princeton, Wisconsin. Kitchen Sink Press, 1990. ISBN 0878161147 (p.6)

- ↑ Wolfgang J Fuchs and Reinhold Reitberger Comics; Anatomy Of A Mass Medium. Boston, Little, Brown, 1972 (p. 254)

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Old Time Radio; John Dunning; p. 122

- ↑ Lesser, Robert. A Celebration of Comic Art and Memorabilia (1975) ISBN 0-8015-1456-8, page number?

- ↑ Buck-Rogers.com - "Buck Rogers" TV Series (1950-51) Archived February 4, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Buck-Rogers.com - "Buck Rogers" TV Series (1950-51) Archived February 4, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Buck battles intergalactic troublemakers Archived February 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., Buck-rogers.com; accessed August 28, 2014.

- ↑ Frank Miller Helming "Buck Rogers", Superhero Hype!, December 19, 2008

- ↑ "Buck Rogers" Blasts Off Into 3-D Space, Deadline.com, March 24, 2010

- ↑ http://www.ign.com/articles/2009/05/15/did-the-spirit-kill-buck-rogers

- 1 2 Buck Rogers Planet of Zoom at the Killer List of Videogames

- ↑ "IGN Presents the History of SEGA". IGN. p. 1. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ↑ Star Fox at Allgame

- ↑ "IGN Presents the History of SEGA". IGN. p. 2. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ↑ World of Spectrum: Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom

- ↑ Atari Age: Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom Standard label

- ↑ Lemon64.com: Buck Rogers: Planet of Zoom, 1983, US Gold

- ↑ http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2049243_2048649_2048998,00.html

- ↑ http://www.toyraygun.com/buckrogersrayguns.html

- ↑ "Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1964)". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (Gold Key)". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (Whitman)". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ "Buck Rogers (TSR)". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ↑ Dynamite Debuts Buck Rogers for a Quarter, Newsarama, February 23, 2009

- ↑ Back to the Future: Barrucci and Beatty on Buck Rogers, Newsarama, February 23, 2009

- ↑ Scott Beatty Talks Buck Rogers, Comic Book Resources, March 6, 2009

- ↑ Drawing the Future: Carlos Rafael on Buck Rogers, Newsarama, March 9, 2009

- ↑ "Exclusive Buck Rogers Graphic Novel Available in May Previews". Comic Bastards. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2015-09-23.

- ↑ Sauriol, Patrick. "First look at the future of Buck Rogers Begins". Corona Coming Attractions.

- ↑ Pascale, Anthony. "Phase II's James Cawley Bringing Buck Rogers To The Web". Trekmovie.com.

- ↑ Bobby Rice at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Samantha Gray Hissong at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Buck Rogers: Exclusive First Look

- ↑ Jones, Brandon. "Gil Gerard: 'Buck Rogers' reboot is dead".

- ↑ http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1796708800/buck-rogers-begins

- ↑ Thomas D. Clareson, Understanding Contemporary American Science Fiction (1992). Univ of South Carolina Press. Page 6. ISBN 0-87249-870-0

- ↑ Mimosa 28, pages 102–107. "Roots and a Few Vines" by Mike Resnick

- ↑ "Restoration Center Open House Highlights". New Mexico Museum of Space History. 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

The DC-X launched vertically, hovered in mid-air at 150 feet, and began to move sideways at a dogtrot. After traveling 350 feet, the onboard global-positioning satellite unit indicated that the DC-X was directly over its landing point. The spacecraft stopped mid-air again and, as the engines throttled back, began its successful vertical landing. Just like Buck Rogers.

- ↑ "SpaceX Continues its Quest to Create a "Buck Rogers" Reusable Rocket". 21st Century Tech. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ↑ Elon Musk, Scott Pelley (2014-03-30). Tesla and SpaceX: Elon Musk's industrial empire (video and transcript). CBS. Event occurs at 03:50–04:10. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

Only four entities have launched a space capsule into orbit and successfully brought it back: the United States, Russia, China, and Elon Musk. This Buck Rogers dream started years ago...

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buck Rogers. |

- ""Buck Rogers" TV Series (1950–51)". Archived from the original on 2005-02-04. Retrieved 2005-02-04.

- Strickler, Dave. Syndicated Comic Strips and Artists, 1924–1995: The Complete Index. Cambria, CA: Comics Access, 1995. ISBN 0-9700077-0-1.

- Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (official website, Buck Rogers and Dille Family Trust) - checked 19 nov 2011—not available

- Buck Rogers at DMOZ