Burhinus

| Burhinus | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Burhinus capensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Burhinidae |

| Genus: | Burhinus Illiger, 1811 |

Burhinus is a genus of bird in the Burhinidae family. This family also contains the genus Esacus.[1] The genus name Burhinus comes from the Greek bous, ox, and rhis, nose.[2]

The Burhinus are commonly called thick-knee, stone-curlew or dikkop. They are medium-sized, terrestrial waders, though they are generally found in semi-arid to arid, open areas. Only some species of Burhinus are associated with water. The genus ranges from 32 cm to 59 cm in size. Burhinus are characterised by their long legs, long wings and cryptic plumage. Most species have a short, thick, strong bill.[1][3] The stone-curlews are found all over the world except Antarctica. They are mainly tropical, with the greatest diversity in the old world.[1]

There are eight species of Burhinus. No species is threatened and none have become extinct since 1600.[1][4]

It contains the following species:

- Bush stone-curlew (Burhinus grallarius)

- Double-striped thick-knee (Burhinus bistriatus)

- Peruvian thick-knee (Burhinus superciliaris)

- Senegal thick-knee (Burhinus senegalensis)

- Spotted thick-knee (Burhinus capensis)

- Eurasian stone-curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus)

- Indian stone-curlew (Burhinus indicus)

- Water thick-knee (Burhinus vermiculatus)

Taxonomy and systematics

Burhinus was first described by Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger in 1811.[5] Determining the correct placement of this family can be difficult as they are very ancient species.[6][7][8] Burhinus are best placed in Charadriiformes. They resemble bustards (family: Otididae) and have been previously classified with them in Gruiformes. Their placement in Gruiformes is considered convergent evolution, as both orders have the same lifestyle and biotopes. Comparisons made of skeleton, biochemistry and parasites plus down on young, confirm Burhinus as a charadriiform.[1]

Based on multi-locus analysis, the stone-curlew family (Burhinidae) is probably closest to the family Charadriidae, not Scolopacidae. The optimal maximum likelihood phylogenetic reconstruction using multi-locus (ADH5, GPD3-5 and FGB-7) analysis placed Burhinus within Charadrii, sister to Scolopaci.[9] They have some similarities to Glareolidae and some phylogenies do place them as a sister clade to this family.[10][11][12] however this is also considered convergent evolution.[1] DNA-DNA hybridisation as well as RAG-1 and myoglobin intron-II sequence data supports a link to Recurvirostridae.[1][13][14] Burhinus and Chionis together are sister to the rest of the Charadriidae.[14][15][16][17]

A phenotypic study of Charadriiformes suggests that Burhinidae should consist of three genera – Esacus, Burhinus plus resurrected Orthorhampus.[18] In this model, the Bush stone-curlew would be removed from Burhinus and placed in a sub-family Esacinae with Esacus. This sub-family would be known as the Greater Thick-knees, while the remainder of the genus Burhinus would fall into Burhininae, the Lesser Thick-knees. This is based on character analyses of skeletons, skin and natal patterns.[18] Esacus has sometimes been lumped within Burhinus, but Esacus are generally larger and chunkier with a larger bill and less mottled plumage. Burhinus is clearly distinct from Esacus, except for the Bush thick-knee, which is the same size as Esacus. However, the Bush thick-knee has more similar plumage to the rest of Burhinus.[1] The Indian stone-curlew was split from the Eurasian species, as it does not migrate.[19] It is possible that the population of Eurasian stone-curlews on the Canary Islands should also be split in this way as this population shows very little genetic variation.[20]

The Bush stone-curlew has had a confusing history of classification. This species has previously been considered two species and B. magnirostris (the designation now used for the Beach stone-curlew) has at times been used for this species leading to much confusion.[1][19] The Bush stone-curlew is now B. grallarius, as described by John Gould in 1845.[1]

Description

Burhinus are a genus of long-legged, large-eyed, terrestrial waders with eerie nocturnal calls. They range from 32 cm (Senegal thick-knee) to 59 cm (Bush stone-curlew).[1][3] There are generally only minor plumage differences between the sexes, and the late juveniles of Burhinus appear similar to the adults. Females may be smaller.[3] All species of this genus have cryptic plumage of sandy browns with streaks and mottles, usually with spots of cream, buff, brown and black. The head of the Burhinus has a broad domed crown, giving rise to the Afrikaans name of dikkop, which translates to “thick head”.[1][3] The closed wings of most Burhinus have banded upper coverts. This is not as prominent on the American species and the Peruvian thick-knee is plainer and greyer except for the head. In flight, Burhinus’ wing plumage is much more striking with patterning that contrasts with the otherwise cryptic plumage. All Burhinus have black primary feathers with white patches, which is most developed in Bush stone-curlews. The wings are long and are held straight and out stretched in flight. Burhinus have a marked carpal angle and the outer wing has minimal tapering, with a pointed tip in some species. The inner wing is thinner, with 16-20 secondary feathers. Burhinus have 11 primary feathers, of which the outer most is very small and covered by the primary coverts. The twelve tail feather are generally short and rounded, except in the Spotted thick-knee which is medium in length and the Bush stone-curlew which has a longer more tapered tail. Their legs often extend beyond the tail in flight.[1][3]

.jpg)

Typically, the Burhinus bill is stout, and is considered medium to short in length for a wader. The tip of the bill is bulbous with sharp point when viewed from side, while from the top view it has a broad base. The bill is mostly dark but can have yellow at the base, with slit-like perforated nostrils like Laridae.[1][3]

The long legs of Burhinus range from pale ochre to vivid yellow in colour. The tibia is exposed and the swollen tibiotarsal (‘knee’ joint – actually ankle) is where name ’thick-knee’ came from. Their legs are markedly scaled and only have three slight webbed, forward facing toes with no hind toe.[1] Burhinus move on the land with a measured sedate walk; head and body held horizontal in the same position to when they lay on the ground. The long strides easily move from walk to run with head held forward. Flight can quickly follow and their flight is fast and direct with little maneuverability. Burhinus will generally run before they take off and run for a short distance on landing. Their active flight consists of regular, shallow wing beats similar to Numenitus.[1]

All Burhinus have a complete post-breeding moult which can take 4–5 months. The primaries are lost in descending sequence. The Eurasian and Senegal thick-knees may suspend moulting of primaries in winter and finish in spring, leading to an overlap of moulting and breeding. It is very unusual for breeding and moulting to overlap, and the slow moult may possibly be to maximise re-nesting potential.[21] Burhinus’ secondary feathers are usually not replaced in one season, with the inner and outer feather being shed first.[22] A pre-breeding moult may just be the head and neck and sometimes not at all. Once they have fledged, juvenile Burhinus will moult only their head and body, some wing-coverts and central tail. Juveniles will moult their secondary wing feathers after their first winter. This can be helpful when estimating the age of young birds.[1][22]

Distribution and habitat

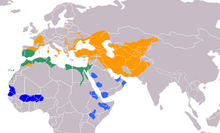

More species of Burhinus species are found in the tropics and sub-tropics, than other bioregions. They are generally sedentary and can live their whole lives within a few kilometres of hatching site. Eurasian stone-curlews are the exception, breeding in temperate areas and migrating south to avoid the northern winter. Birds from Britain and France will migrate to Italy, Greece, and Turkey and further.[1][19][22] Bush stone-curlews will move to find food.[3] Both Eurasian and Bush stone-curlews use a much larger area outside the breeding season.[1][3][23] Double-striped, Peruvian and the Spotted thick-knees are rarely seen outside breeding areas while Senegal thick-knees will move based on rains in north.[1]

Burhinus are very typical in their requirements and are usually found in dry open country though the Senegal and Water thick-knees are associated with water. They can breed in arid and semi-arid habitats but not in closed woodland or forest. They are generally found in open spaces with extensive visibility on dry fairly even ground. Their habitat is usually a mixture of bare earth and vegetation with some species, like the Bush stone-curlew, found in lightly timbered, open forest and woodland. Eurasian stone-curlews are mostly found on free draining sandy soils with stones, both semi-natural and tilled.[23] They will roost in the shade at the edge of a forest. Partly cleared farmland can be used as well but intense cultivation will drive them away.[1][3][24][25] Burhinus are generally timid and wary, though in some case they may live close to humans using resources from dung and crops, as well as nesting on rooftops.[1][3][26]

Behaviour and ecology

Burhinus are terrestrial and often only fly when surprised, despite being strong flyers. When observed, Burhinus will generally look furtive and secretive and prefer to stay motionless. They roost on the ground during the day beside clumps of vegetation, rock or fallen timber. Most species are active from dusk till dawn.[1][3][26] Feeding and social displays occur from dusk, and this may be one reason why displays are mostly vocal rather than including flight and/or demonstrations like other waders. The exception is the Water Thick-knee, which can be more active during the day.[1][27]

_-_Flickr_-_Lip_Kee.jpg)

Burhinus can be sociable with non-breeding flocks of dozens to hundreds using traditional sites In Europe, 300 or more Eurasian stone-curlews have been seen together at times, whilst in Tunisia, 150 have been recorded together. Non-breeding Spotted stone-curlews can sometimes be found in loose flocks of 50 also during breeding season.[1] Peruvian thick-knees are more likely to stay in large flocks year round in Chile than in Peru, where flocks increase after breeding. Variations in flocking behaviour over the species range may be influenced by differences in local predation, foraging and climate pressures.[23] The resting position of Burhinus may be more upright than when feeding, with the head hunched at shoulder and tail down, tarsus on ground and tibia upright. If alarmed, Burhinus will bob their head, they will then freeze or walk away if possible, rather than flying.[1][3]

Diet and feeding

The diet of Burhinus is quite uniform between the species, as is the method of consumption. Food items include insects (beetles, crickets, grasshoppers) plus crustaceans, molluscs, worms, centipedes, spiders, other bird’s eggs, small mammals, reptiles and frogs. Eurasian and Bush stone-curlews may also consume a small amount of vegetation and seeds. The chicks will eat the same items as the adults, however fewer spiders are taken.[23] Food is picked up from the ground with the bill, probed from soft soil and wood, or gleaned from low vegetation. Burhinus will hit larger prey on the ground before swallowing it. Flying insects may be taken from the air. The Eurasian stone-curlew will forage in dung.[1][3][23] Burhinus forage on dry open ground, sometimes under trees, among crops pasture and grass, on saltpans, irrigation paddocks and riverbeds. In the summer, Burhinus will spend more time foraging along watercourses, dams and swamps. Burhinus will forage for 20–30 minutes in one area then fly short distance to next. When Burhinus are actively feeding, they will move slowly, pausing and tilting their head like plovers. More active prey will be chased over short distance or the bird will lunge for the prey.[1][3][28]

Breeding

Eurasian stone-curlews are the best-studied species, however what is known about other species aligns with Eurasian information in many instances. Burhinus form monogamous, long-term (probably lifelong) pairs.[1][29] For the more tropical species, the breeding season is opportunistic, depending on the availability of food and nesting sites, while the temperate species nest in the spring and summer. Generally, nesting will consist of solitary pairs, if possible, but when the population is dense or the habitat restricted, multiple pairs may be found nesting in close proximity, especially Double-striped and Senegal stone-curlews. Courtship consists of short runs, skips and leaps with open wings and the black and white wing/tail patches may possibly be important. Displays may be between two birds or in a group.[1] Bush stone-curlews have a dramatic dance that is quite well described. They stand erect with wings out and vertical with black and white patterns showing. They run on the spot with high steps, all the time repeating wails of increasing speed, final screams and trills. This will be repeated multiple times.[1][3]

Eurasian stone-curlews will select a nest site with a bowing display – forward leaning with head and neck downward sometimes with the bill touching the ground. The male indicates a spot, female shuffle onto that spot and scrapes. Birds take turns to sit on scrape, shuffling and turning, pick up twigs and stones and throwing away. This process will be repeated in multiple sites before selecting one. Bowing performance at scrape before eggs are laid with arched posture ‘neck-arch’ display, then relaxing, before mating. Mating is more frequent in early stages of nest selection and reduces until just before eggs are laid.[1]

Location of Burhinus’ nests can vary and may be near vegetation or out in the open.[1][30] The nest usually consists of a simple scrape that is sometimes lined with stones or shells.[1] Placement of nest site in different habitats such as heath-land or farmland can vary from year to year by the same pairs.[31] If the vegetation becomes too tall, as can occur if nesting occurs within a crop, Burhinus will abandon the nest site.[31] Senegal thick-knee will use grit, straw, wood and shells to line its nest, while Spotted thick-knee uses smaller animal dung and vegetation to line the nest. Double-striped thick-knee may also use dung to line their nest. Water thick-knee will use more lining than other species and usually place the nest near a piece of driftwood or vegetation, sometimes on elephant dung.[1][27] Bush stone-curlews nest under trees of open woodland with understorey of short sparse or lush grass, often near dead timber.[1][3]

Both parents incubate (for 24–27 days), defend and rear offspring. The male can be more aggressive. Burhinus chicks are partially independent by four weeks. Some species of Burhinus will only have one clutch, unless eggs or chicks are lost, while other will have two. The length of time with parents depends on whether there is a second clutch. If a second clutch is laid, then the older offspring will be pushed away. Chicks are independent at 2–3 months. Pairs may move on from territory if their eggs or chicks are taken.[1][20][32]

Clutch size is two eggs, rarely three, laid at 2-day intervals. Egg size is specific to species and the eggs are usually rounded ovals, smooth slightly glossy, whitish or buffish with brown spots and mottles. Burhinus’ eggs match with the ground, nesting building and choice of nest substrate preferred by each species and individual variation occurs. This increases crypsis and improves hatching success.[33] Incubation begins when the last egg is laid but sometime just before with synchronous or consecutive hatching. Broken shells are carried away.[1][29][33]

Burhinus chicks are precocial and nidifugous. They have long stout legs and thick down. The parents will guard and collect food for them when very young. They will also lead them to feeding ground over quite a large area. Bush stone-curlews have been seen lifting young after brooding and the Senegal thick-knee is suspected of carrying their chicks. The parents will warn chicks to lay down when disturbed and the chicks will drop down, head and neck stretched out, making them very difficult to see.[1][20][34]

Minor disturbances will cause parents to quietly leave nest, while more serious threats will cause them to defend the nest. This can include distraction displays and aggressive behaviour, though very occasionally a broken wing display has been observed. The non-incubating parent will spot danger and warn their mate. The alarm is raised with a special posture. The sitting bird will walk away then runs and flies off, while the other bird flies in different direction. They will both turn back and meet, and watch to see what will become of the disturbance. The male will follow intruder if it leaves, whilst the female will carefully return. The pair will attack ground predators, diving, wings out and neck forward. On the other hand, they will stand upright wing fanned against herbivore that may trample the eggs or chicks. If chicks are not lost to the threat, the parents will lead them to a new area. Senegal thick-knees will watch humans at nest and then return quite quickly even if watched.[1][20][32]

Voice

Burhinus are mainly silent during the day, with the majority of call occurring during the night. Their call is penetrating and far-carrying and has been described as eerie, mournful and plaintive. They can produce remarkable vocal performances including wailing and whistling. Eurasian stone-curlews often make short sharp notes like oyster-catchers (Haematopodidae), which are repeated, accelerating to up more prolonged curlew like calls and then dies away. Senegal stone-curlew is more nasal; while the Double-striped thick-knee produces shorter but still strident calls. Peruvian Stone-curlews are locally called ‘Huerequeque” which is a transliteration of their voice, while the Aborigine name for Bush stone-curlew is “Willaroo” which is onomatopaeic to the long drawn out whistling scream. Several individuals will join in a prolonged chorus, especially at the beginning of breeding season.[1][32]

The role of the calls of Burhinus is poorly understood due to the difficulty of observation of individuals while calling. Eurasian stone-curlews are the best studied and it has been found that:

- groups are more vocal than pairs;

- vocals may be more important between adjacent pairs than within the pair;

- more vocal in pre-lay period, silent when newly arrived in breeding territory, quiet again before chicks arrive and until fledging;

- more daytime calling occurs while establishing a territory or from unpaired or non-breeding birds, and these birds are more easily attracted by call playback.[1]

Vocalisations usually start approximately thirty minutes after sunset and started by single individual, and then partner and other pairs join in. The birds are quieter in middle of night and finish at sunrise. Adults call more frequently during the spring and summer. Some calls have no context, however a number of calls have been described for Eurasian stone-curlews.[30] Vocalisations for adults include aggression, greeting between pairs or groups of territory holders meeting, specific behaviours like nest scraping and spring displays, distraction behaviours, adults defending their nest with eggs or chicks as well as conversational calls between adults over newly hatched chicks. Calls from chicks and juveniles up to 70 days old have also been documented, with two types completely different to adults.[1][30]

Status and conservation

It is very difficult to know the true status of this genus, as its species are so secretive. There is just enough data to show that most species of Burhinus have been affected by interference.[1] Some species have suffered steep declines in some areas leading to local extinction.[1][3][25] Habitat destruction, urban development, intense cultivation, forestry, tourism, subdivisions, over grazing and burning, as well as introduced predators are some of the factors threatening Burhinus.[1][3][20][26][30][31][34] The most study has been done on the Eurasian stone-curlew.[1][24][31][35][36] In Britain, sensitive management of grazing in heathlands, setting aside patches within crops, and the protection of nests from predators, machinery and stock has led to a halt of the very sharp decline of the Eurasian stone-curlew, with this population now stable though not increasing.[1][3][31] Modelling the habitat required for stone-curlews, as well as the use of ringing recovery, geo-locators and GPS data loggers, has also helped to determine which areas are important to protect for Eurasian stone-curlews in both Britain and Italy.[24][32] The Bush stone-curlew has contracted in its range, with reduced numbers or local extinction in the south and east.[3]

The African thick-knees will often live alongside people and generally ignore them. In these places, the populations seem stable and stone-curlews will use the resources provided by humans such as feeding on insects in livestock dung and nesting on roofs.[26] Some modification seems to be beneficial where suitable habitat is produced as a result, for example along road-sides for the American species, however this can lead to mortality as well.[1]

Relationship with humans

Due to their secretive nature, Burhinus mainly come to the attention of humans through their calls, leading to varied local names. The calls of the Bush stone-curlew caused unease to white settlers as well as Aboriginal people in Australia, especially because they are hard to see, which added to the fear and superstition. The main reference in folklore is to a vague, disembodied voice in the night. In some places, the Double-striped stone-curlew is kept semi-captive to help keep pests under control. The yellow eyes and bill of the Eurasian stone-curlew was once thought to indicate that they were good treatment for jaundice.[1]

Gallery

-

Bush stone-curlew

-

Double-striped thick-knee

-

.jpg)

PeruviantThick-knee

-

Cape thick-knee

-

Stone-curlew

-

Water thick-knee

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J (1996) Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol 3. Lynx, Barcelona

- ↑ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Marchant, S., & P.J. Higgins (eds) 1993. Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 2: Raptors to Lapwings. Oxford University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 0-19-553069-1

- ↑ IUCN 2015. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015-4. http://www.iucnredlist.org Archived June 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.. Downloaded on 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Gray GR (1841) A List of the Genera of Bird:With Their Synonyma and an Indication of the Typical Species of Each Genus. R. & J.E. Taylor, London.

- ↑ Ericson PGP, Christidis L, Cooper A, Irestedt M, Jackson J, Johansson US and Norman JA: A Gondwanan origin of passerine birds supported by DNA sequences of the endemic New Zealand wrens. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Ser B 2002, 269:235-241

- ↑ van Tuinen M, Sibley CG and Hedges SB: The early history of modern birds inferred from DNA sequences of nuclear and mitochondrial ribosomal genes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2000, 17:451-457.

- ↑ García-Moreno J and Mindell DP: Rooting a phylogeny with homologous genes on opposite sex chromosomes (gametologs): a case study using avian CHD. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2000, 17:1826-1832.

- ↑ Fain MG and Houde P (2007) Multilocus perspectives on the monophyly and phylogeny of the order Charadriiformes (Aves). BMC Evolutionary Biology 7:35.

- ↑ Chu PC (1995) Phylogenetic reanalysis of Strauch’s osteological data set for the Charadriiformes. The Condor 97:174–196

- ↑ Strauch J (1978) The phylogeny of the Charadriiformes (Aves): a new estimate using the method of character compatibility analysis. Trans Zool Soc Lond 34:263–345

- ↑ Mayr G (2011) The phylogeny of charadriiform birds (shorebirds and allies)––reassessing the conflict between morphology and molecules. Zool J Linn Soc 161:916–934

- ↑ Sibley CG & Ahlquist JE (1990) Phylogeny and classification of birds. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

- 1 2 Ericson PGP, Envall I, Irested M and Norman JA (2003) Inter-familial relationships of the shorebirds (Aves: Charadriiformes) based on nuclear DNA sequence data. BMC Evolutionary Biology 3:16.

- ↑ Paton TA, Baker AJ, Groth JG, Barrowclough GF (2003) RAG-1 sequences resolve phylogenetic relationships within charadriiform birds. Mol Phylogen Evol 29:268–278

- ↑ Paton TA, Baker AJ (2006) Sequences from 14 mitochondrial genes provide a well-supported phylogeny of the charadriiform birds congruent with the nuclear RAG-1 tree. Mol Phylogen Evol 39:657–667

- ↑ Baker AJ, Pereira SL, Paton TA (2007) Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times of Charadriiformes genera: multigene evidence for the Cretaceous origin of at least 14 clades of shorebirds. Biol Lett 3:205–209

- 1 2 Livezey BC (2009) Phylogenetics of modern shorebirds (Charadriiformes) based on phenotypic evidence: analysis and discussion. Zool Jour Linn Soc 160:567–618.

- 1 2 3 Sharma M, Sharma RK (2015) Ecology and Breeding Biology of Indian Stone Curlew (Burhinus indicus). Nat. Env. & Poll. Tech. 14(2):423-426

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mori A, Baldaccini NE, Baratti M, Caccamo C, Dessì-Fulgheri F, Grasso R, Nouira S, Ouni R, Pollonara E, Rodriguez-Godoy F, Spena MT, Giunchi D (2014) A first assessment of genetic variability in the Eurasian Stone-curlew Burhinus oedicnemus. Ibis 156(3):687-692.

- ↑ Giunchi D, Caccamo C & Pollonara E (2008) Pattern of Wing Moult and Its Relationship to Breeding in the Eurasian Stone-Curlew Burhinus oedicnemus. Ardea, 96(2):251-260.

- 1 2 3 Giunchi D, Chiara C, Mori A, Fox JW, Rodrıguez-Godoy F, Baldaccini NE, Pollonara E (2015) Pattern of non-breeding movements by Stone-curlews Burhinus oedicnemusbreeding in Northern Italy. J Ornithol 156:991–998

- 1 2 3 4 5 Camacho, C (2012) Variations in flocking behaviour from core to peripheral regions of a bird species’ distribution range. Acta ethol 15:153-158.

- 1 2 3 Smith PJ, Pressey RL & Smith JE (1994) Birds of particular conservation concern in the Western Division of New South Wales. Biological Conservation 69(3):315-338.

- 1 2 Thiollay JM (2006) Large bird declines with increasing human pressure in savanna woodlands (Burkina Faso). Biodiversity and Conservation 15:2085–2108.

- 1 2 3 4 Green RE, Tyler GA and Bowden CGR (2000) Habitat selection, ranging behaviour and diet of the stone curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus) in southern England. J. Zool. 250:161-183

- 1 2 Solis JC and de Lope F (1995) Nest and egg crypsis in the ground-nesting Stone Curlew Burhinus oedicnemus. J Avian Biol 26:135-138

- ↑ Caccamo C, Pollonara E. Baldaccini NE & Giunchi D (2011) Diurnal and nocturnal ranging behaviour of Stone-curlews Burhinus oedicnemus nesting in river habitat. Ibis153:707–720:

- 1 2 Freese CH (1975) Notes on Nesting in the Double-Striped Thick-Knee (Burhinus bistriatus) in Costa Rica. The Condor 77(3):353-354

- 1 2 3 4 Green RE & Griffiths GH (1994) Use of preferred nesting habitat by stone curlews Burhinus oedicnemus in relation to vegetation structure. J Zool 233(3): 457–471.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carter A (2010) Improving red fox (Vulpes vulpes) management for bush stone curlew (Burhinus grallarius) conservation in south-eastern Australia. Ph.D. Thesis, Charles Sturt University, Albury.

- 1 2 3 4 Dragonetti M, Caccamo C, Corsi F, Farsi F, Giovacchini P, Pollonara E and Giunchi D (2013) The Vocal Repertoire of the Eurasian Stone-Curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus).The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 125(1):34-49.

- 1 2 Williams MD (1981) Description of the nest and eggs of the Peruvian Thick-knee (Burhinus superciliaris). The Condor 83(2):183-184

- 1 2 Gates JA & Paton DC (2005) The distribution of Bush Stone-curlews (Burhinus grallarius) in South Austral, with particular reference to Kangaroo Island. EMU 105, 241-247

- ↑ Thompson S, Hazel A, Bailey N, Bayliss J, Lee JT (2004) Identifying potential breeding sites for the stone curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus) in the UK. Jour Nat Cons 12(4):229-235.

- ↑ Paker Y, Yom-Tov Y, Alon-Mozes T and Barnea A (2014) The effect of plant richness and urban garden structure on bird species richness, diversity and community structure.Landscape and Urban Planning 122:186– 195.