Catherine Helen Spence

| Catherine Helen Spence | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Catherine Helen Spence in the 1890s | |

| Born |

31 October 1825 Melrose, Scotland |

| Died |

3 April 1910 (aged 84) Norwood, South Australia |

| Occupation | Author, teacher, journalist and politician |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Ethnicity | Scottish |

| Notable works | Clara Morison: A Tale of South Australia During the Gold Fever |

.jpg)

Catherine Helen Spence (31 October 1825 – 3 April 1910) was a Scottish-born Australian author, teacher, journalist, politician, leading suffragist, and Georgist.[1] In 1897 she became Australia's first female political candidate after standing (unsuccessfully) for the Federal Convention held in Adelaide. Called the "Greatest Australian Woman" by Miles Franklin and given the nomenclature of "Grand Old Woman of Australia' on her eightieth birthday, Spence was commemorated on the Australian five-dollar note issued for the Centenary of Federation of Australia.

Early life

Spence was born in Melrose, Scotland, as the fifth child in a family of eight.[2] In 1839, following sudden financial difficulties, the family emigrated to South Australia. Arriving on 31 October 1839 (her 14th birthday), on the Palmyra, at a time when the colony had experienced several years of drought, the contrast to her native Scotland made her "inclined to go and cut my throat". Nevertheless, the family endured seven months "encampment", growing wheat on an eighty-acre (32 ha) selection before moving to Adelaide.

Her father, David Spence, was elected first Town Clerk of the City of Adelaide.[3] Her brother John Brodie Spence was a prominent banker and parliamentarian and her sister Jessie married Andrew Murray.

Journalism and literature

Spence had a talent for writing and an urge to be read, so it was natural that in her teens she became attracted to journalism. Through family connections, she began with short pieces and poetry published in The South Australian. She also worked as a governess for some of the leading families in Adelaide, at the rate of sixpence an hour. For several years, Spence was the South Australian correspondent for The Argus newspaper writing under her brother's name until the coming of the telegraph.

Her first work was the novel Clara Morison: A Tale of South Australia During the Gold Fever. It was initially rejected but her friend John Taylor, found a publisher in J W Parker and Son and it was published in 1854. She received forty pounds for it, but was charged ten pounds for abridging it to fit in the publisher's standard format. Her second novel Tender and True was published in 1856, and to her delight went through a second and third printing, though she never received a penny more than the initial twenty pounds. Then followed her third novel, published in Australia as Uphill Work and in England as Mr Hogarth's Will, published in 1861 and several more though some were unpublished in her lifetime including Gathered In (unpublished until 1977) and Hand fasted (unpublished until 1984).

In 1888 she published A Week In the Future, a tour-tract of the utopia she imagined a century in the future might bring; it was one of the precursors of Edward Bellamy's 1889 Looking Backward.

Her final work, called A Last Word, was lost while still in manuscript form.

Social work and issues

Although Spence rejected both of the two proposals of marriage she received during her life, and never married, she had a keen interest in family life and marriage – as applied to other people. Both her life's work and her writing were devoted to raising the awareness of, and improving the lot of, women and children. She successively raised three families of orphaned children – the first being those of her friend Lucy Duval.

She was one of the prime movers, with C. Emily Clark (sister of John Howard Clark), of the "Boarding-out Society". This organization had as its aim removing destitute children from the asylum into approved families and to eventually remove all children from institutions except the delinquent.[3] At first treated with scorn by the South Australian Government, the scheme was encouraged when the institutions devoted to the handling of troublesome boys became overcrowded. These two were also appointed to the State Children's Council, which controlled the Magill Reformatory.[4] C H Spence was also the only female member of the Destitute Board.

Religion

Around 1850, having become disillusioned with some doctrines of the Church of Scotland, she began attending the Adelaide Unitarian Christian Church in Wakefield Street.[5] She preached her first sermons there in 1878,[2] (though she was not the first woman to preach there, that honour going to Martha Turner of Melbourne, sister of Gyles Turner)[6] and filled in for the pastor Dr John Crawford Woods during his absences 1884–90.

Politics and "effective voting"

She was an advocate of Thomas Hare's scheme for the representation of minorities, at one stage considering this issue more pressing than that of woman suffrage.[3]

She traveled and lectured both at home and abroad on what she called Effective Voting that became known as Proportional Representation. She lived to see it adopted in Tasmania.

Support of the arts

She was an early advocate of the work of Australian artist Margaret Preston and purchased her 1905 still-life "Onions". Preston received a commission to paint a portrait of Spence in 1911 from a citizens' committee of Adelaide; now held by the Art Gallery of South Australia.[7]

Recognition

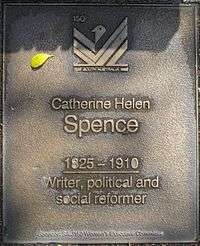

There are numerous memorials to Spence around the Adelaide city centre, including:

- a bronze statue in Light Square

- the Catherine Helen Spence building in the City West campus of the University of South Australia

- the Spence wing of the State Library of South Australia

- Catherine Helen Spence Street in the south-east of the city centre

- a plaque on the Jubilee 150 Walkway on North Terrace

The posthumous portrait of her, by Rose McPherson (later to become famous as Margaret Preston) is held by the Art Gallery of South Australia.[8] This portrait was used as the basis of her appearance on an edition of the Australian five dollar note.[9]

In 1975 she was honoured on a postage stamp bearing her portrait issued by Australia Post.[10]

The Catherine Helen Spence Memorial Scholarship was instituted by the South Australian Government in her honour. See separate article for a list of recipients.

Her image appears on the commemorative Centenary of Federation Australian five-dollar note issued in 2001.

One of the four schools at Aberfoyle Park, South Australia was named Spence in her honour. That school has since been amalgamated with another school to form Thiele Primary School.

The name of the suburb Spence in the ACT is sometimes mistakenly associated with Catherine Spence, but was actually named after the unrelated William Guthrie Spence.

Bibliography

Novels

- Clara Morison: A Tale of South Australia During the Gold Fever (1854)

- Tender and True: A Colonial Tale (1856)

- Mr. Hogarth's Will (1865) originally serialised as Uphill Work in the (Adelaide) Weekly Mail[3]

- The Author's Daughter (1868) originally serialised as Hugh Lindsay's Guest in the (Adelaide) Observer[3]

- Gathered In serialised in Observer and Journal and Queenslander, possibly never published in book form[3]

- An Agnostic's Progress from the Known to the Unknown (1884)

- A Week in the Future (1889)

- Handfasted (1984) Penguin Originals ISBN 0-14-007505-4

Non fiction

- A Plea for Pure Democracy (1861) pamphlet praised by John Stuart Mill and Thomas Hare[3]

- The laws we live under (1880) for South Australian Education Department[3]

- State children in Australia: A history of boarding out and its developments (1909) principally dealing with the work of Emily Clark This book was used by the British Home Secretary when at the end of her reign Queen Victoria asked him to formulate Child Laws in Britain that up until that time were non-existent. He wrote and thanked her for her work.

- Catherine Helen Spence: An autobiography (1910) (unfinished, but completed posthumously by Spence's friend Jeanne Young, working from diaries.)

References

- ↑ Magarey, Susan (1985). Unbridling the tongues of women : a biography of Catherine Helen Spence. Sydney, NSW: Hale & Iremonger. p. 135. ISBN 0868061492.

- 1 2 Eade, Susan (1976). "Spence, Catherine Helen (1825–1910)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. 6: 167–168. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Miss C. H. Spence South Australian Register 4 April 1893 p.5 accessed 26 May 2011

- ↑ "The Egg-Laying Competition.". The Advertiser. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 5 March 1904. p. 10. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ↑ Ever Yours, C H Spence ed. Susan Magarey, Wakefield Press ISBN 978-1-86254-656-1. Google books

- ↑ "Stories of Early Adelaide". The Mail. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 24 July 1943. p. 11. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Seivl, Isobel, 'Preston, Margaret Rose (1875–1963)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed 6 April 2012

- ↑ "If Jewels Could Only Speak.". The Mail. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 25 December 1937. p. 14. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ Catherine Helen Spence on the five-dollar-note

- ↑ Catherine Spence 1825–1910, "Famous Australian Women" postage stamp issue, Australia Post

External links

- "Catherine Helen Spence: a bibliography", State Library of South Australia

- Works by Catherine Helen Spence at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Catherine Helen Spence at Internet Archive

- Works by Catherine Helen Spence at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Gathered In: A novel at Sydney University

- Mr. Hogarth's Will at Sydney University

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Spence, Catherine Helen". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

- Susan Magarey Unbridling the Tongues of Women: a biography of Catherine Helen Spence, University of Adelaide Press, 214 pp, ISBN 978-0-9806723-0-5 Free Download

- Vicki Moore Grand Old Woman of Australia (1996) A stage play State Library of South Australia Manuscripts

- Vicki Moore Catherine Helen Spence: An Essay Makers of Miracles The Cast of the Federation Story Melbourne University Press

- Office for Women