Cambridge Castle

| Cambridge Castle | |

|---|---|

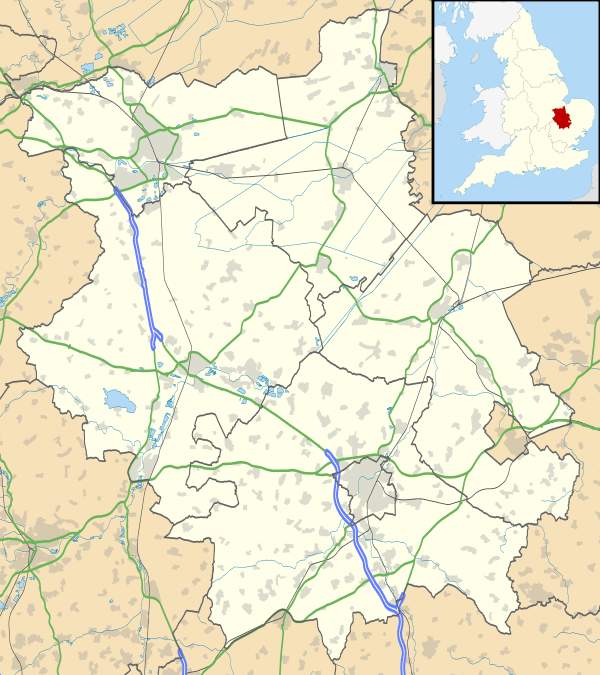

| Cambridgeshire, England | |

|

Castle Mound today | |

Cambridge Castle | |

| Coordinates | grid reference TL44475923 |

| Type | Motte and bailey |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Cambridgeshire County Council |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | The motte and fragments of earthworks survive |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Stone |

| Events | The Anarchy, the First and Second Barons' Wars |

Cambridge Castle, locally also known as Castle Mound, is located in Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England. Originally built after the Norman conquest to control the strategically important route to the north of England, it played a role in the conflicts of the Anarchy, the First and Second Barons' Wars. Hugely expanded by Edward I, the castle then fell rapidly into disuse in the late medieval era, its stonework recycled for building purposes in the surrounding colleges. Cambridge Castle was refortified during the English Civil War but once again fell into disuse, used primarily as the county gaol. The castle gaol was finally demolished in 1842, with a new prison built in the castle bailey. This prison was demolished in 1932, replaced with the modern Shire Hall, and only the castle motte and limited earthworks still stand. The site is open to the public daily and offers views over the historic buildings of the city.

History

11th century

Cambridge Castle was one of three castles built across the east of England in late 1068 by William the Conqueror in the aftermath of his northern campaign to capture York.[1][nb 1] Cambridge, or Grantabridge as it was then known, was on the old Roman route from London to York and was both strategically significant and at risk of rebellion.[3] The initial building work was conducted by Picot, the high sheriff, who later founded a priory beside the castle.[4] The castle was built in a motte and bailey design, within the existing town, and 27 houses had to be destroyed to make space for it.[5]

12th-13th centuries

The castle was held by the Norman kings until the civil war of the Anarchy broke out in 1139.[6] Castles played a key role in the conflict between the Empress Matilda and King Stephen, and in 1143 Geoffrey de Mandeville, a supporter of the Empress, attacked Cambridge; the town was raided and the castle temporarily captured.[6] Stephen responded with a counter-attack, forcing Geoffrey to retreat into the Fens and retaking the castle.[7] Cambridge Castle remained exposed, however, and Stephen decided to build a supporting fortification at Burwell to provide additional protection.[8] Geoffrey died attacking Burwell Castle the following year, leaving Cambridge Castle secure.[8]

Under Henry II the castle was adequately maintained, but little additional work was undertaken to improve it.[9] A castle-guard system was established, under which lands around Cambridge were granted to local lords on the condition that they provide guard forces for the castle, and the castle was primarily used to hold the sheriff's court and records.[10] King John expanded the castle in the years before the First Barons' War of 1215 to 1217, but this work was concentrated on constructing a new hall and chamber, at the cost of £200.[11][nb 2] During the war, the rebel barons, supported by Prince Louis of France, captured much of eastern England; Cambridge Castle fell in 1216.[13] The castle was returned to royal control after the war, but Henry III only conducted basic maintenance of the fortification.[14] Cambridge was attacked again during the Second Barons' War in 1266.[15] This time the town and castle held long enough to be relieved by Henry's forces, but the king reinforced the city defences with a large ditch, later known as King's Ditch.[15]

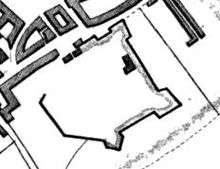

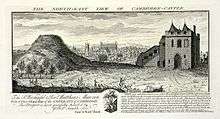

Cambridge Castle remained only a basic fortification until 1284 when Edward I decided to undertake major expansion works.[14] Over the next 14 years the king spent at least £2,630 on rebuilding the castle in stone.[14][nb 3] Edward's castle was four-sided, with circular towers at each corner, guarded by a gatehouse and a barbican.[16] A circular stone keep was built on the motte.[16] The result was a "major fortress in the latest fashion", albeit never quite completed.[16] Edward stayed at the castle for two nights in 1294.[15]

14th-17th centuries

During the 14th century the castle was allowed to fall into disrepair.[15] From Edward III onwards, little money was spent on maintaining the property and by the 15th century the castle was in ruins.[16] The castle hall and chamber were roofless by the 15th century, and Henry VI ordered these buildings to be destroyed and the stone reused for constructing King's College in 1441, with other parts of the castle being used to help build Trinity College's chapel.[17] More stonework was given away by Mary I in the 16th century for building a mansion at nearby Scawston in the Fens, and other grants of stone given to Emmanuel and Magdalene colleges.[18] By 1604 only the gatehouse, used as a gaol, and the keep remained intact, with the surrounding walls described by contemporaries as "rased and utterly ruinated".[16]

Civil war broke out in England in 1642 between the rival factions of the Royalists and Parliament. Cambridge Castle was occupied by Parliamentary forces in the first year of the war.[19] Oliver Cromwell ordered emergency work to be conducted to repair the defences, resulting in two new earthwork bastions being added to the castle and a brick barracks constructed in the old bailey.[20] The governor of Cambridge described in 1643 that "our town and castle are now very strongly fortified... with breastworks and bulwarks".[21] The castle saw no further fighting during the war, and in 1647 parliament ordered the remaining fortifications to be slighted, damaged beyond further use.[16]

18th-19th centuries

The castle rapidly deteriorated after the slighting and the remaining walls and bastions were taken down in 1785, leaving only the gatehouse and the earth motte.[20] The gatehouse remained in use as the county gaol into the 19th century, being run, like other similar prisons, as a private business — the keeper of the castle gaol was paid £200 (equivalent to £13,100 in 2009 prices) a year by the county in 1807.[22]

This came to an end when a new county prison was built in the grounds of the castle's former bailey.[23] The new prison was built by G. Byfield between 1807 and 1811 with an innovative octagonal structure, influenced by the designs of the prison reformer John Howard; the castle gatehouse was then destroyed to make way for a new county court building.[24]

Today

The only remaining parts of the medieval castle left today is the 10 metre (33 feet) high motte, which rests on the highest point in the city, and some fragments of the surrounding earthworks.[25] It is open to the public daily with no admission fee, and offers views over the historic buildings of the city. Both the motte and earthworks are Scheduled Ancient Monuments.[26] The site of the castle bailey and the 19th century prison is now occupied by the Cambridgeshire County Council's headquarters at Shire Hall, built in 1932.[25]

Shire Hall viewed from the mound with the steps leading up the mound |

Cambridge skyline viewed from the mound. The church in the foreground is St Giles Church, the spire on the left is part of All Saints Church, the tower on the centre is part of St John's College chapel, and the long roofline on the right is King's College Chapel. |

See also

Notes

- ↑ The other two eastern castles built that year were Lincoln and Huntingdon Castle.[2]

- ↑ It is notoriously difficult to accurately convert medieval financial figures into modern equivalents. For comparison, £200 is around two-thirds of the annual income of a "well-to-do" baron of the period.[12]

- ↑ It is notoriously difficult to accurately convert medieval financial figures into modern equivalents. For comparison, £2,620 is around nine times the annual income of a "well-to-do" baron of the period.[12]

References

- ↑ Mackenzie, p.310, Pounds, p.7.

- ↑ Pounds, p.7.

- ↑ Pounds, p.57.

- ↑ Pounds, p.58.

- ↑ Pounds, p.208.

- 1 2 Bradbury, p.144.

- ↑ Bradbury, p.145.

- 1 2 Bradbury, p.146.

- ↑ Brown, p.171.

- ↑ Pounds, pp.46, 98; Brown, p.71.

- ↑ Mackenzie, p.310; Brown, p.71.

- 1 2 Pounds, p.139.

- ↑ Pounds, p.116.

- 1 2 3 Brown, p.71.

- 1 2 3 4 Mackenzie, p.310.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brown, p.73.

- ↑ Brown, p.73; Mackenzie, p.310.

- ↑ Mackenzie p.310; Brown, p.73.

- ↑ Wedgwood, p.106.

- 1 2 Mackenzie, p.311; Brown, p.73.

- ↑ Thompson, p.139.

- ↑ Finn, p.135; 2009 equivalent prices using the Measuring Worth website, accessed 29 January 2011.

- ↑ Pounds, p.100; The Cambridge Guide, p.212.

- ↑ Mackenzie, p.311; Cambridge Castle, Heritage Gateway, accessed 28 January 2011.

- 1 2 Cambridge Castle, Cambridgeshire Country Council, accessed 29 January 2011.

- ↑ Cambridge Castle mound, Ancient Monuments, accessed 13 July 2011; 'Civil War earthworks at the Castle', Ancient Monuments, accessed 13 July 2011.

Bibliography

- Anon. (1837) The Cambridge Guide: including historical and architectural notices of the public buildings, and a concise account of the customs and ceremonies of the university. Cambridge: Deighton. OCLC 558127530.

- Bradbury, Jim. (2009) Stephen and Matilda: the Civil War of 1139-53. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-3793-1.

- Brown, Reginald Allen. (1989) Castles From The Air. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32932-3.

- Finn, Margot C. (2003) The Character of Credit: Personal Debt in English Culture, 1740-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82342-5.

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896) The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, Vol II. New York: Macmillan.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1990) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a social and political history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Thompson, M. W. (1994) The Decline of the Castle. Leicester, UK: Harveys Books. ISBN 1-85422-608-8.

- Wedgwood, C. V. (1970) The King's War: 1641–1647. London: Fontana. OCLC 58038493.

Coordinates: 52°12′45″N 0°06′47″E / 52.2124°N 0.1131°E