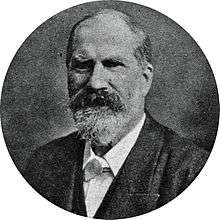

Hardwicke Rawnsley

Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (29 September 1851 – 28 May 1920), was a Church of England clergyman, poet, hymn writer, local politician, and conservationist. He was also one of the founders of the National Trust.

Living in the English Lake District for more than thirty years, he worked for the protection of the countryside and secured the support of people of influence for his campaigns.

Biography

Early years

Rawnsley was born at the rectory, Shiplake, Oxfordshire, England, the fourth of ten children of the Rev Robert Drummond Burrell Rawnsley (1817–1882) and his wife, Catherine Ann, née Franklin (1818–1892).[1] An older brother, Willingham Franklin Rawnsley, became an author and schoolmaster. He was educated at Uppingham School and Balliol College, Oxford, where he was prominent in university athletics and rowing.[2] He gained a third class degree in natural science in 1874 and was awarded his Master of Arts degree in 1875.[3] In the same year he was ordained as a deacon in the Church of England and became the first chaplain of Clifton College mission, ministering to one of Bristol's poorest areas.

The Lake District

In 1877 Rawnsley was ordained as a priest, and in 1878 he took up the post of Vicar of Wray, Windermere, in the Lake District.[1] In January 1878, he married Edith Fletcher,[1] and the couple had one child, a son, Noel.[4]

In 1882, the young Beatrix Potter holidayed in nearby Wray Castle with her parents. They entertained many eminent guests, including Rawnsley. His views on preserving the natural beauty of Lake District had a lasting effect on Potter, who was already taken with the area. He was the first published author she met, and he took a great interest in her drawings, later encouraging her to publish her first book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit.[5]

Rawnsley became engaged in local campaigns to protect the countryside. In 1883, having secured the support of Robert Hunter, solicitor to the Commons Preservation Society, the social reformer Octavia Hill, and John Ruskin, under whose influence Rawnsley had come while at Oxford, Rawnsley successfully led a campaign to prevent the construction of railways to carry slate from the quarries above Buttermere, which would have ruined the unspoilt valleys of Newlands and Ennerdale.[4] This success led to the formation of the Lake District Defence Society (later to become The Friends of the Lake District). Besides Rawnsley, members included Robert Browning, the Duke of Westminster, Ruskin, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, with whom Rawnsley had a family connection.[4][5]

In 1883 Rawnsley was appointed Vicar of Crosthwaite, near Keswick, and Rural Dean.[1] In 1891 was appointed as an honorary canon of Carlisle Cathedral.[5] In 1884 he and his wife began organising classes in metalwork and wood carving, which resulted in the establishment of a School of Industrial Art in Keswick, which remained in operation until 1986.[5] His interest in education also led him to take a large part in founding Keswick High School, which opened in October 1898, one of the first co-educational secondary schools in the country.[4][6]

In 1888 Rawnsley was elected as a member of the new Cumberland County Council and became chairman of its Highways Committee.[7] He stood out against the construction of roads over lakeland passes, secured controls over mining pollution, and promoted adequate signposting of footpaths.[4] Other targets for his reforming zeal included the brewing industry and in later years the cinema, where he was strongly against the depiction of sex and violence.[4] While he opposed what he saw as excessive numbers of public houses, he was not a prohibitionist. In the last month of his life, after returning from a tour of French vineyards, he wrote to The Times protesting against Britain's high tax on the importation of French wine, which he saw as unfair and as contributing to rural poverty in France.[8]

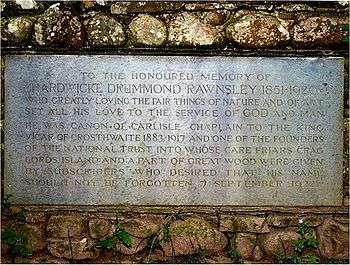

To protect the countryside from damaging development, Rawnsley, building on an idea propounded by Ruskin, conceived of a National Trust that could buy and preserve places of natural beauty and historic interest for the nation. The Trust became a reality in 1895; its co-founders were Rawnsley, Octavia Hill and Sir Robert Hunter. Until his death, Rawnsley worked as Honorary Secretary to the Trust. He was responsible for the campaign to raise money to buy Brandlehow Wood, the National Trust's first purchase in the Lake District.[5]

Later years

In 1898, Rawnsley was offered the bishopric of Madagascar, but declined it, feeling himself committed to his conservation work in the Lake District and, by then, in many other parts of the British countryside.[4] In 1912 he was appointed to the largely honorary position of chaplain to the King,[1] and he held the post of chaplain to the Border Regiment of the Territorial Force, with the rank of colonel.[2]

Rawnsley published more than forty books, mostly non-fiction, some on religious subjects, many with a Lake District theme, and, as the Dictionary of National Biography put it, "as a minor lake poet, a vast output of verse."[4][5] His memoir of Ruskin, described by The New York Times as "in many ways the best volume [of] his series of books upon some of the literary aspects of the Lake Country",[9] was published in 1901.[1]

After 34 years at Crosthwaite he retired to Grasmere, where, in 1915, he had bought Allan Bank, the house in which William Wordsworth had lived between 1807 and 1813. Edith Rawnsley died in 1916, and two years later, Rawnsley married Eleanor "Nellie" Foster Simpson, who had been his secretary and was also an author.[2][5] She completed his biography, published by Maclehose, Jackson & Co in 1923. Rawnsley died at his home in Grasmere and is buried in the churchyard of his former parish, St. Kentigern's, Crosthwaite. He bequeathed Allan Bank to the National Trust, with Eleanor living there until her death in 1959.[5] In its obituary notice, The Times said of him, "It is no exaggeration to say – and it is much to say of anyone – that England would be a much duller and less healthy and happy country if he had not lived and worked."[2]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Rawnsley, Rev. Hardwicke Drummond", Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edition, Oxford University Press, December 2007, accessed 17 May 2009

- 1 2 3 4 The Times, Obituary, 29 May 1920, p. 11

- ↑ The Manchester Guardian, 4 June 1875, p. 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Murphy, Graham. "Rawnsley, Hardwicke Drummond (1851–1920)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 17 May 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley", Visitcumbria.com, accessed 17 May 2009

- ↑ The Manchester Guardian, 22 November 1906, p. 14

- ↑ The Manchester Guardian dated 7 November 1895, p. 5

- ↑ The Times, 26 April 1920, p. 10

- ↑ The New York Times, 1 March 1902, Page BR7

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Hardwicke Rawnsley |

- Works by or about Hardwicke Rawnsley at Internet Archive

- Biography at Visit Cumbria

- Beatrix Potter's Lake District (Liverpool Museums)

- Poems, Ballads, and Bucolics, by Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley

- A Book of Bristol Sonnets, by Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley

- Ruskin and the English Lakes, by Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley