Carmine Crocco

| Carmine Crocco | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

5 June 1830 |

| Died |

18 June 1905 (aged 75) Portoferraio, Tuscany |

| Other names | Donatello |

| Organization | Brigandage in the Two Sicilies |

Carmine Crocco, known as Donatello or sometimes Donatelli[1] (5 June 1830 – 18 June 1905), was an Italian brigand. Initially a Bourbon soldier, later he fought in the service of Giuseppe Garibaldi. Soon after the Italian unification he formed an army of two thousand men, leading the most cohesive and feared band in southern Italy and becoming the most formidable leader on the Bourbon side.[2] He was renowned for his guerrilla tactics, such as cutting water supplies, destroying flour-mills, cutting telegraph wires and ambushing stragglers.[3]

Although some authors of the 19th and the early 20th century regarded him as a "wicked thief and assassin"[4] or a "fierce thief, vulgar murderer",[5] since the second half of the 20th century writers (especially supporters of the Revisionism of Risorgimento) began to see him in a new light, as an "engine of the peasant revolution"[6] and a "resistant ante litteram, one of the most brilliant military geniuses that Italy had".[7]

Today many people of southern Italy, and in particular of his native region Basilicata, consider him a folk hero.[8]

Life

Youth

Crocco was born into a family of five children in Rionero in Vulture, which was at the time part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. His father, Francesco Crocco, was a servant of the noble Santangelo family from Venosa and his mother, Maria Gerarda Santomauro, was a housewife. His uncle Martino was a veteran of the Napoleonic army who fought in Spain during the Peninsular War, losing a leg, probably in the siege of Saragossa. Crocco grew up with the tales of his uncle, from whom he learned to read and write. While a child, Crocco began to develop an aversion towards the upper class, after his brother was beaten by don Vincenzo, a young lord, for killing a dog who had attacked a Crocco family chicken. His mother, pregnant at that time, tried to defend her son but the lord kicked her in the belly, forcing her to abort.[9] His father was later accused of the attempted murder of don Vincenzo and was imprisoned without sufficient proof.[10]

During his adolescence, Crocco moved to Apulia, to work as a shepherd, along with his brother, Donato. In 1845, Crocco saved the life of don Giovanni Aquilecchia, a nobleman of Atella, who had tried to cross the raging waters of the Ofanto River. Aquilecchia rewarded him with 50 ducats, permitting Crocco to eventually return to his home town from Apulia and find a new job. Crocco had the opportunity to meet don Pietro Ginistrelli, Aquilecchia's brother-in-law, who was able to secure the release of his father from prison.[11]

However, by the time he was released Francesco Crocco was old and sick and this left Crocco to act as head of his family, working as a farmer in Rionero. Here he met don Ferdinando, don Vincenzo's son, who felt regret for his father's behavior against the family. Don Ferdinando offered him a job as a farmer on his property, but Crocco preferred to take money instead, which he used to avoid the military service, as during the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, service was avoidable upon payment. The nobleman accepted but was killed on 15 May 1848 in Naples by some Swiss troops. Thus Crocco had to join Ferdinand II's army, but he deserted as a result of killing a comrade in a brawl.[2] In his absence, his sister Rosina had to take care of the family.

Becoming an outlaw

During Crocco's absence. his sister, Rosina, then not yet eighteen years old, was courted by a nobleman, Don Peppino. Rosina was not interested in him and rejected him. Annoyed by his refusal, Peppino proceeded to defame her.[11]

When Crocco heard about these events he was angry and decided to avenge his sister. Knowing the habits of Peppino, who generally attended a particular club to gamble in the evening hours, Crocco awaited his return at Peppino's home. When Don Peppino arrived, Crocco questioned him but the discussion ended in a fight, after Peppino hit Crocco with a whip.[11]

Blinded by rage, Crocco pulled out a knife, killed Peppino and then fled to the Forenza woods. However this account is controversial because Captain Eugenio Massa, who collaborated on the Crocco's autobiography, conducted a detailed investigation on the spot and could not confirm that a murder had taken place in the circumstances described by Crocco.[12]

While in hiding, Crocco met other outlaws and together they formed a band that lived on the proceeds of blackmail and robbery. Crocco returned to Rionero but was arrested on 13 October 1855. He escaped during the night of 13-14 December 1859, hiding in the woods between Monticchio and Lagopesole.[13]

Expedition of the Thousand

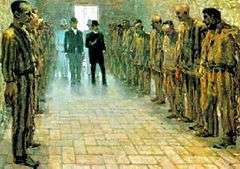

.jpg)

At the same time Giuseppe Garibaldi was launching his Expedition of the Thousand, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was soon on the verge of collapse, requiring all forces remaining at its command to confront Garibaldi. Garibaldi managed to defeat them, gain control of Sicily and then cross to the mainland, where he moved swiftly north towards Naples.[14]

Garibaldi promised to forgive the deserters in exchange for military service and Crocco joined Garibaldi's army hoping for a pardon as well as other rewards.[15] Crocco accompanied Garibaldi north to Naples and took part in the famous Battle of Volturnus. Although he displayed courage in battle, Crocco did not receive any medals or other honors and was also arrested.[16]

He was taken to the prison in Cerignola but, with the help of noble Fortunato family (relatives of the politician Giustino), he was able to get away. Disappointed by the new Italian government's lies, Crocco was persuaded by noblemen linked to Bourbons and the local clergy to join the legitimist cause.

Meanwhile, Basilicata's population began to rise against the new government, because it did not get any benefit with the political change and became even poorer than before, while the bourgeois class (faithful to the Bourbons in the past) maintained its privileges, after having supported the cause of the Italian unification opportunistically.[17] With the war and pecuniary support of the legitimists, he recruited an army of 2000 men,[18] beginning the resistance under the flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

In the service of Francis II

In 10 days, Crocco and his army occupied the entire Vulture area. In the conquered territory he ordered the badges and ornaments of the king Francis II to be once again displayed. The raids were bloody, ruthless and many people (especially liberal politicians and wealthy landowners) were kidnapped, blackmailed or brutally killed by Crocco himself or his members but, in most cases, people of lower classes regarded him as a "liberator" and supported his bands.[19]

On 7 April 1861 Crocco occupied Lagopesole and, the day after, Ripacandida, where he defeated the local garrison of the "Italian National Guard". On 10 April 1861, his army entered Venosa and sacked it. During the siege of Venosa, Crocco's men killed Francesco Nitti, a physician and an ex-member of the Carbonari, as well as grandfather of the politician Francesco Saverio Nitti.[20] Subsequently Lavello was invaded, where he set up a court which judged 27 liberals and the municipal coffers were emptied of 7,000 ducats, 6,500 of which were distributed to the people[21] and then Melfi. Crocco's army also conquered parts of Campania (Sant'Angelo dei Lombardi, Monteverde, Conza, Teora),[22] Apulia (Bovino and Terra di Bari).[23]

Impressed by his victories, the Bourbon government in exile sent the Spanish General José Borjes to Basilicata, to reinforce and discipline the bands and warning the band chief about an imminent reinforcement of soldiers. The goal of Borjes was the capitulation of Potenza, the most well-defended stronghold of the Italian army in Basilicata. Crocco did not trust Borjes from the start and worried about losing his leadership, but he accepted the alliance. Meanwhile, another legitimist agent arrived: Augustin De Langlais from France, an ambiguous person about which little is known of his life, including the reason for his presence among the brigands.[24]

Crocco, with the support of Borjes and De Langlais, conquered other towns searching for new recruits, including Trivigno, Calciano, Garaguso, Craco and Aliano. Crocco's army made its way to Potenza, occupying neighboring cities such as Guardia Perticara, San Chirico Raparo and Vaglio, but the expedition to the main city failed because of a clash between Crocco and Borjes on the military campaign.

After other battles and retreating to Monticchio, one of his headquarters, Crocco broke the alliance with Borjes because he did not want to serve under a foreigner and did not believe the promise of the Bourbon government about the provision of reinforcements. Disappointed, Borjes planned to go to Rome, to inform King Francis II but, during the journey, he was captured in Tagliacozzo and shot by Piedmontese soldiers headed by Major Enrico Franchini.

Last days

Without external support, Crocco turned to plundering and extortion to raise funds, cooperating with like-minded confederates and making raids from Molise to Apulia. Vespasiano De Luca, director of Public Safety in Rionero, invited him to sign a treaty of surrender but Crocco declined. Even without the help of the Bourbons, Crocco, skilled in guerrilla warfare, was able to harass the Piedmontese soldiers. Faced with the apparent invincibility of Crocco's army, the Hungarian Legion (who helped Garibaldi during the expedition of the thousand) intervened in support of the royal coalition.[25]

Suddenly, Crocco was betrayed by Giuseppe Caruso, one of his lieutenants. Caruso went to the Piedmontese authorities and revealed Crocco's location and hideouts. Under the command of General Emilio Pallavicini (known to have stopped Garibaldi's expedition against Rome in the calabrian mountains), the royal army engaged and defeated Crocco. His band suffered many casualties, and some of his lieutenants, such as Ninco Nanco and Giuseppe "Sparviero" Schiavone, were captured and executed by firing squad, leaving Crocco to retire toward the Ofanto zone. After losing the last battle, he was forced to flee to the Papal States, hoping for help from Pius IX, whom he knew had previously supported the southern opposition.[26]

Upon arrival Crocco was captured by papal troops in Veroli and imprisoned in Rome. He was then turned over to the Italian authorities and sentenced to death on 11 September 1872 in Potenza, but the sentence was commuted to hard labour for life. He was imprisoned on Santo Stefano Island, where he began writing his memoirs, with the help of Eugenio Massa, captain of the royal army, which published them in 1903, under the name Gli ultimi briganti della Basilicata (The last brigands of Basilicata). The manuscript was republished in the post-World War II era by other authors like Tommaso Pedio (1963), Mario Proto (1994) and Valentino Romano (1997).[27] Crocco was later transferred to the prison at Portoferraio, where he died on 18 June 1905.

Legacy

Crocco is the main character of the production La Storia Bandita (The Bandit's Story) that is held every year in Brindisi Montagna. Artists such as Michele Placido, Antonello Venditti and Lucio Dalla have participated in the production.[28]

The movie Il Brigante di Tacca del Lupo (1952), directed by Pietro Germi, is vaguely based on the Crocco's story.

He appears in the second episode of the Italian TV drama L'eredità della priora (1980) by Anton Giulio Majano.

He made a cameo appearance in the film 'o Re (1989) directed by Luigi Magni.

He is the main protagonist of the 1999 movie Li chiamarono... briganti! (They called them... brigands!) directed by Pasquale Squitieri, starring Enrico Lo Verso (in the role of Crocco), Claudia Cardinale, Remo Girone, Franco Nero among the others. The movie was unsuccessful and was quickly suspended from its run in cinemas, although reviewers claimed that the truth was uncomfortable to some viewers.[29]

He is the main protagonist of the TV film Il generale dei briganti (2012) by Paolo Poeti; Crocco is played by Daniele Liotti.

The Italian actor Michele Placido, son of an immigrant from Rionero, claims to be a descendant of Crocco on his father's side.[28]

The Italian musician Eugenio Bennato dedicated the song Il Brigante Carmine Crocco, from the 1980 album Brigante se more to him.

In November 2008, a museum dedicated to Crocco, named La Tavern r Crocc (English: The Tavern of Crocco) was opened in his home town.[30]

Some of Crocco's band members

Giuseppe Nicola Summa, nicknamed "Ninco Nanco"

Giuseppe Nicola Summa, nicknamed "Ninco Nanco" "Caporal" Teodoro Gioseffi

"Caporal" Teodoro Gioseffi Agostino Sacchitiello (center)

Agostino Sacchitiello (center) Vito "Totaro" Di Gianni (right) with his men

Vito "Totaro" Di Gianni (right) with his men Giuseppe "Sparviero" Schiavone

Giuseppe "Sparviero" Schiavone Michele "Il Guercio" Volonnino

Michele "Il Guercio" Volonnino From l. to r.: Filomena Pennacchio, Giuseppina Vitale, Maria Giovanna Tito (Crocco's fiancée)

From l. to r.: Filomena Pennacchio, Giuseppina Vitale, Maria Giovanna Tito (Crocco's fiancée)

References

- ↑ Tommaso Pedio, Storia della Basilicata raccontata ai ragazzi, p. 264

- 1 2 Eric J. Hobsbawm, Bandits, p.25

- ↑ John Ellis, A short history of guerrilla warfare, p.83

- ↑ Vittorio Bersezio, Il regno di Vittorio Emanuele II, Roux e Favale, 1895, p. 25

- ↑ Basilide Del Zio, Il brigante Crocco e la sua autobiografia Tipografia G. Grieco, 1903, p.116

- ↑ Carlo Alianello, L'eredità della priora, Feltrinelli, 1963, p. 568

- ↑ Nicola Zitara (14 July 2004). "li chiamarono... BRIGANTI!" (in Italian). eleaml.org. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Mario Monti, I briganti italiani, vol.2, p.17

- ↑ Indro Montanelli, L'Italia dei notabili. (1861-1900), p.85

- ↑ Tommaso Pedio, Storia della Basilicata raccontata ai ragazzi, p.264

- 1 2 3 Tommaso Pedio, Storia della Basilicata raccontata ai ragazzi, p.265

- ↑ Basilide Del Zio, Il brigante Crocco e la sua autobiografia, p.120

- ↑ Antonio De Leo, Carmine Cròcco Donatelli: un brigante guerrigliero, p.36

- ↑ Tommaso Pedio, Storia della Basilicata raccontata ai ragazzi, p.266

- ↑ Denis Mack Smith, Italy:a modern history, p.72

- ↑ Indro Montanelli, L'Italia dei notabili. (1861-1900), p.86

- ↑ Tommaso Pedio, La Basilicata Borbonica, Lavello, 1986, p. 7

- ↑ Sergio Romano, Storia d'Italia dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni, p.49

- ↑ Indro Montanelli, L'Italia dei notabili. (1861-1900), p.88

- ↑ Francesco Barbagallo, Francesco Saverio Nitti, p. 5

- ↑ Renzo Del Carria, Proletari senza rivoluzione, p.87

- ↑ A. Maffei count, Marc Monnier, Brigand life in Italy: a history of Bourbonist reaction, Volume 2, p.39

- ↑ Aldo De Jaco, Il brigantaggio meridionale, p.218

- ↑ Benedetto Croce, Uomini e cose della vecchia Italia, p.324

- ↑ Basilide Del Zio, Il brigante Crocco e la sua autobiografia, p. 159-160

- ↑ Nicholas Atkin, Frank Tallet, Priests, prelates and people: a history of European Catholicism since 1750, p.134

- ↑ Raffaele Nigro. "Il brigantaggio nella letteratura" (in Italian). eleaml.org. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Rossani Ottavio, Grassi Giovanna (June 25, 2000). ""La storia bandita": un film dal vivo sui briganti" (in Italian). Corriere della sera. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Lorenzo Del Boca, Indietro Savoia!, p. 231.

- ↑ "La Tavern R Crocc" (in Italian). Retrieved 15 March 2011.

Sources

- David Hilton Wheeler, Brigandage in south Italy, Volume 2, S. Low, son, and Marston, 1864.

- A. Maffei count, Marc Monnier, Brigand life in Italy: a history of Bourbonist reaction, Volume 2, Hurst and Blackett, 1865, p. 342.

- John Ellis, A short history of guerrilla warfare, Allan, 1975.

- Eric J. Hobsbawm, Bandits, Penguin, 1985.

- Tommaso Pedio, Storia della Basilicata raccontata ai ragazzi, Congedo, 1994.

- Antonio De Leo, Carmine Cròcco Donatelli: un brigante guerrigliero, Pellegrini, 1983.

- Denis Mack Smith, Italy:a modern history, University of Michigan Press, 1969.

- Indro Montanelli, L'Italia dei notabili. (1861-1900), Rizzoli, 1973.

- Basilide Del Zio, Il brigante Crocco e la sua autobiografia, Tipografia G. Grieco, 1903.

- Francesco Barbagallo, Francesco Saverio Nitti, UTET, 1984.

- Nicholas Atkin, Frank Tallet, Priests, prelates and people: a history of European Catholicism since 1750, I.B.Tauris, 2003.

- Renzo Del Carria, Proletari senza rivoluzione, Savelli, 1975

- Aldo De Jaco, Il brigantaggio meridionale, Editori riuniti, 2005.

- Benedetto Croce, Uomini e cose della vecchia Italia, Laterza, 1927

- Mario Monti, I briganti italiani, vol.2, Longanesi, 1967.

- Sergio Romano, Storia d'Italia dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni, Longanesi, 1998.

- Pedio, Tommaso; Mario Proto (1995). Come divenni brigante: autobiografia di Carmine Crocco. Piero Lacaita Editore. pp. 106 pag.

- Lorenzo Del Boca, Indietro Savoia!, Piemme, 2003.

- Perrone, Adolfo (1963). Il brigantaggio e l'unità d'Italia. Istituto Editoriale Cisalpino. pp. 279 pag.

- Ettore Cinnella, Carmine Crocco. Un brigante nella grande storia, Della Porta, 2016, second edition.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carmine Crocco. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Carmine Crocco |

- The New York Times: Italian Brigandage. The story of Crocco - The hero of one hundred and thirty crimes

- Rivista Anarchica: State massacres of the nineteenth century