Casino Royale (1967 film)

| Casino Royale | |

|---|---|

|

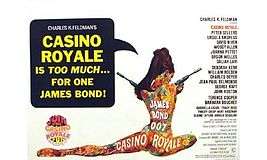

British cinema poster by Robert McGinnis | |

| Directed by |

Ken Hughes John Huston Joseph McGrath Robert Parrish Val Guest Richard Talmadge (uncredited) |

| Produced by |

Charles K. Feldman Jerry Bresler |

| Screenplay by |

Wolf Mankowitz John Law Michael Sayers |

| Based on |

Casino Royale by Ian Fleming |

| Starring |

Peter Sellers Ursula Andress David Niven Woody Allen Joanna Pettet Orson Welles Daliah Lavi |

| Music by | Burt Bacharach |

| Cinematography |

Jack Hildyard, BSC Nicolas Roeg, BSC John Wilcox, BSC |

| Edited by | Bill Lenny |

Production company |

Famous Artists Productions |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 131 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million |

| Box office | $41.7 million |

Casino Royale is a 1967 spy comedy film originally produced by Columbia Pictures starring an ensemble cast of directors and actors. It is loosely based on Ian Fleming's first James Bond novel. The film stars David Niven as the "original" Bond, Sir James Bond 007. Forced out of retirement to investigate the deaths and disappearances of international spies, he soon battles the mysterious Dr. Noah and SMERSH. The film's slogan: "Casino Royale is too much... for one James Bond!" refers to Bond's ruse to mislead SMERSH in which six other agents are pretending to be "James Bond", namely, baccarat master Evelyn Tremble (Peter Sellers); millionaire spy Vesper Lynd (Ursula Andress); Bond's secretary Miss Moneypenny (Barbara Bouchet); Mata Bond (Joanna Pettet), Bond's daughter with Mata Hari; and British agents "Coop" (Terence Cooper) and "The Detainer" (Daliah Lavi).

Charles K. Feldman, the producer, had acquired the film rights in 1960 and had attempted to get Casino Royale made as an Eon Productions Bond film; however, Feldman and the producers of the Eon series, Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, failed to come to terms. Believing that he could not compete with the Eon series, Feldman resolved to produce the film as a satire. The budget escalated as various directors and writers got involved in the production, and actors expressed dissatisfaction with the project.

Casino Royale was released on 13 April 1967, two months prior to Eon's fifth Bond movie, You Only Live Twice. The film was a financial success, grossing over $41.7 million worldwide, and Burt Bacharach's musical score was praised, earning him an Academy Award nomination for the song "The Look of Love". Critical reception to Casino Royale, however, was generally negative; some critics regarded it as a baffling, disorganised affair. Since 1999, the film's rights have been held by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, distributors of the official Bond movies by Eon Productions.

Plot summary

Sir James Bond 007, a legendary British spy who retired from the secret service 20 years previously, is visited by the head of British MI6, M, CIA representative Ransome, KGB representative Smernov, and Deuxième Bureau representative Le Grand. All implore Bond to come out of retirement to deal with SMERSH who have been eliminating agents: Bond spurns all their pleas. When Bond continues to stand firm, his mansion is destroyed by a mortar attack at the orders of M, who is, however, killed in the explosion.

Bond travels to Scotland to return M's remains to the grieving widow, Lady Fiona McTarry. However, the real Lady Fiona has been replaced by SMERSH's Agent Mimi. The rest of the household have been likewise replaced, with SMERSH’s aim to discredit Bond by destroying his "celibate image". Attempts by a bevy of beauties to seduce Bond fail, but Mimi/Lady Fiona becomes so impressed with Bond that she changes loyalties and helps Bond to foil the plot against him. On his way back to London, Bond survives another attempt on his life.

Bond is promoted to the head of MI6. He learns that many British agents around the world have been eliminated by enemy spies because of their inability to resist sex. Bond is also told that the "sex maniac" who was given the name of "James Bond" when the original Bond retired has gone to work in television. He then orders that all remaining MI6 agents will be named "James Bond 007", to confuse SMERSH. He also creates a rigorous programme to train male agents to ignore the charms of women. Moneypenny recruits "Coop", a karate expert who begins training to resist seductive women: he also meets an exotic agent known as the Detainer.

Bond then hires Vesper Lynd, a retired agent turned millionaire, to recruit baccarat expert Evelyn Tremble, whom he intends to use to beat SMERSH agent Le Chiffre. Having embezzled SMERSH's money, Le Chiffre is desperate for money to cover up his theft before he is executed.

Following up a clue from agent Mimi, Bond persuades his estranged daughter Mata Bond to travel to East Berlin to infiltrate International Mothers' Help, an au pair service that is a cover for a SMERSH training center. Mata uncovers a plan to sell compromising photographs of military leaders from the US, USSR, China and Great Britain at an "art auction", another scheme Le Chiffre hopes to use to raise money: Mata destroys the photos. Le Chiffre's only remaining option is to raise the money by playing baccarat.

Tremble arrives at the Casino Royale accompanied by Lynd, who foils an attempt to disable him by seductive SMERSH agent Miss Goodthighs. Later that night, Tremble observes Le Chiffre playing at the casino and realises that he is using infrared sunglasses to cheat. Lynd steals the sunglasses, allowing Evelyn to eventually beat Le Chiffre in a game of baccarat. Lynd is apparently abducted outside the casino, and Tremble is also kidnapped while pursuing her. Le Chiffre, desperate for the winning cheque, hallucinogenically tortures Tremble. Lynd rescues Tremble, only to subsequently kill him. Meanwhile, SMERSH agents raid Le Chiffre's base and kill him.

In London, Mata Bond is kidnapped by SMERSH in a giant flying saucer, and Sir James and Moneypenny travel to Casino Royale to rescue her. They discover that the casino is located atop a giant underground headquarters run by the evil Dr. Noah, secretly Sir James' nephew Jimmy Bond, a former MI6 agent who defected to SMERSH to spite his famous uncle. Jimmy reveals that he plans to use biological warfare to make all women beautiful and kill all men over 4-foot-6-inch (1.37 m) tall, leaving him as the "big man" who gets all the girls. Jimmy has already captured The Detainer, and he tries to convince her to be his partner; she agrees, but only to dupe him into swallowing one of his "atomic time pills", turning him into a "walking atomic bomb".

Sir James, Moneypenny, Mata and Coop manage to escape from their cell and fight their way back to the Casino Director's office where Sir James establishes Lynd is a double agent. The casino is then overrun by secret agents and a battle ensues. American and French support arrive, but just add to the chaos. Eventually, Jimmy's atomic pill explodes, destroying Casino Royale with everyone inside. Sir James and all of his agents then appear in heaven, and Jimmy Bond is shown descending to hell.

Cast

Sixteen actors were named in the opening credits, with a number of them given the additional designation "James Bond 007" during the film, as a plot device to confuse the party (SMERSH) trying to kill James Bond:

- Peter Sellers as Evelyn Tremble/James Bond 007 – A baccarat master recruited by Vesper Lynd to challenge Le Chiffre at Casino Royale.

- Ursula Andress as Vesper Lynd/James Bond 007 – A retired British secret agent forced back into service in exchange for writing off her tax arrears.

- David Niven as Sir James Bond – A legendary British secret agent forced out of retirement to fight SMERSH.

- Orson Welles as Le Chiffre – SMERSH's financial agent, desperate to win at baccarat to repay the money he has embezzled from the organisation.

- Joanna Pettet as Mata Bond/James Bond 007 – Bond's daughter, born of his love affair with Mata Hari.

- Daliah Lavi as The Detainer/James Bond 007 – A British secret agent who successfully poisons Dr. Noah with his own atomic pill.

- Woody Allen as Dr. Noah/Jimmy Bond 007 – Bond's nephew and head of SMERSH under his Dr. Noah alias.

- Deborah Kerr as Agent Mimi/Lady Fiona McTarry – A SMERSH agent who masquerades as the widow of M but cannot help falling in love with Bond.

- William Holden as Ransome – A CIA executive who accompanies the cross-spy-agency team to persuade Bond out of retirement, then reappears in the final climactic fight scene.

- Charles Boyer as LeGrand – A Deuxième Bureau executive who accompanies the cross-spy-agency team to see Bond.

- John Huston as M/McTarry – Head of MI6 who dies from an explosion caused by his own bombardment of Bond's estate when the cross-spy-agency team visits.

- Kurt Kasznar as Smernov – A KGB executive who accompanies the cross-spy-agency team to see Bond.

- George Raft as himself

- Jean-Paul Belmondo as French Legionhaire

- Terence Cooper as Coop/James Bond 007 – A British secret agent specifically chosen, and trained for this mission to resist the charms of women.

- Barbara Bouchet as Miss Moneypenny/James Bond 007 – The beautiful daughter of Bond's original Miss Moneypenny. She works for the service in the same position her mother had years before.

Major stars like George Raft and Jean-Paul Belmondo were given top billing in the film's promotion and screen trailers despite the fact that they only appeared for a few minutes in the final scene.[1]

Other well known (then, or later) actors include:

- Jacqueline Bisset (credited as Jacky Bisset) as Giovanna Goodthighs – A SMERSH agent who attempts to kill Evelyn Tremble at Casino Royale.

Also, as an extra who stands behind Le Chiffre at the casino.[2] - Bernard Cribbins as Carlton Towers – A British Foreign Office official who drives Mata Bond all the way from London to Berlin in his taxi.

- Ronnie Corbett as Polo – A SMERSH agent at the International Mothers' Help who was in love with Mata Hari and expresses the same feelings for Mata Bond.

- Anna Quayle as Frau Hoffner – Frau Hoffner is Mata Hari's teacher, portrayed as a parody of Cesare in the German Expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (her school is modelled on the film's expressionist decor).

- Geoffrey Bayldon as Q.

Casino Royale also takes credit for the greatest number of actors in a Bond film either to have appeared or to go on to appear in the rest of the Eon series – besides Ursula Andress in Dr. No, Vladek Sheybal appeared as Kronsteen in From Russia with Love, Burt Kwouk featured as Mr. Ling in Goldfinger and an unnamed SPECTRE operative in You Only Live Twice, Jeanne Roland plays a masseuse in You Only Live Twice, and Angela Scoular appeared as Ruby Bartlett in On Her Majesty's Secret Service. Jack Gwillim, who had a tiny role as a British army officer, played a Royal Navy officer in Thunderball. Caroline Munro, who can be seen very briefly as one of Dr Noah's gun-toting guards, received the role of Naomi in The Spy Who Loved Me. Milton Reid, who appears in a bit part as the temple guard, opening the door to Mata Bond's hall, played one of Dr. No's guards and Stromberg's underling, Sandor, in The Spy Who Loved Me. John Hollis, who plays the temple priest in Mata Bond's hall, went on to play the unnamed figure clearly intended to be Blofeld in the pre-credits sequence of For Your Eyes Only. John Wells, Q's assistant, appeared in For Your Eyes Only as Denis Thatcher. Hal Galili, who appears briefly as a US army officer at the auction, had earlier played gangster Jack Strap in Goldfinger.

Uncredited cast

Well established stars like Peter O'Toole and sporting legends like Stirling Moss took uncredited parts in the film just to be able to work with the other members of the cast.[1] Stunt director Richard Talmadge employed Geraldine Chaplin to appear in a brief Keystone Cops insert. The film also proved to be young Anjelica Huston's first experience in the film industry as she was called upon by her father, John Huston, to cover the screen shots of Deborah Kerr's hands.[1] The film also marks the debut of Dave Prowse, later the physical form of Darth Vader in the Star Wars series, as Frankenstein's monster, a role he would later play again in the Hammer films The Horror of Frankenstein and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell. John Le Mesurier features in the early scenes of the film as M's driver.[3]

Production

Development

In March 1955 Ian Fleming sold the film rights of his novel Casino Royale, the first book featuring the character of James Bond, to the producer Gregory Ratoff for $6,000[4] ($53,091 in 2016 dollars).[5] In 1956 Ratoff set up a production company with Michael Garrison to produce a film adaptation, but wound up not finding financial backers before his death in December 1960.[6] After Ratoff's death, the producer Charles K. Feldman represented Ratoff's widow and obtained the Casino Royale rights.[7] Albert R. Broccoli, who had a long time interest in adapting James Bond, offered to purchase the Casino Royale rights from Feldman, but he declined.[8] Feldman and his friend, the director Howard Hawks, had an interest in adapting Casino Royale, considering Leigh Brackett as a writer and Cary Grant as James Bond. They eventually gave up once they saw the 1962 film Dr. No, the first Bond adaptation made by Broccoli and his partner Harry Saltzman through their company Eon Productions.[9]

By 1964, with Feldman having invested nearly $550,000 of his own money into pre-production of Casino Royale, he decided to try a deal with Eon Productions and its distributor United Artists. The attempt at a co-production eventually fell through as Feldman frequently argued with Broccoli and Saltzman, specially regarding the profit divisions and when the Casino Royale adaptation would start production. Feldman approached Sean Connery to play Bond, with Connery's offering to do the film for one million dollars being rejected.[10] Feldman eventually decided to offer his project to Columbia Pictures through a script written by Ben Hecht, and the studio accepted. Given Eon's series led to a spy film craze at the time, Feldman opted to make his film a spoof of the Bond series instead of a straightforward adaptation.[11]

Screenplay development

Ben Hecht's contribution to the project, if not the final result, was in fact substantial. The Oscar-winning writer was recruited by Feldman to produce a screenplay for the film and wrote several drafts, with various evolutions of the story incorporating different scenes and characters. All of his treatments were "straight" adaptations, far closer to the original source novel than the spoof which the final production became. A draft from 1957 discovered in Hecht's papers – but which does not identify the screenwriter – is a direct adaptation of the novel, albeit with the Bond character absent, instead being replaced by a poker-playing American gangster.[6]

Later drafts see vice made central to the plot, with the Le Chiffre character becoming head of a network of brothels (as he is in the novel) whose patrons are then blackmailed by Le Chiffre to fund Spectre (an invention of the screenwriter). The racy plot elements opened up by this change of background include a chase scene through Hamburg's red light district that results in Bond escaping whilst disguised as a female mud wrestler. New characters appear such as Lili Wing, a brothel madam and former lover of Bond whose ultimate fate is to be crushed in the back of a garbage truck, and Gita, wife of Le Chiffre. The beautiful Gita, whose face and throat are hideously disfigured as a result of Bond using her as a shield during a gunfight in the same sequence which sees Wing meet her fate, goes on to become the prime protagonist in the torture scene that features in the book, a role originally Le Chiffre's.[6]

Virtually nothing from Hecht's scripts were ever filmed. He died from a heart attack in April 1964, two days before he was due to present it to Feldman. Time reported in 1966 that the script had been completely re-written by Billy Wilder, and by the time the film reached production only the idea that the name James Bond should be given to a number of other agents remained. This key plot device in the finished film, in the case of Hecht's version, occurs after the demise of the original James Bond (an event which happened prior to the beginning of his story) which, as Hecht's M puts it "not only perpetuates his memory, but confuses the opposition."[6]

Peter Sellers hired Terry Southern to write his dialogue (and not the rest of the script) to "outshine" Orson Welles and Woody Allen.[12]

Filming

The principal filming was carried out at Pinewood Studios, Shepperton Studios and Twickenham Studios in London. Extensive sequences also featured London, notably Trafalgar Square and the exterior of 10 Downing Street. Mereworth Castle in Kent was used as the home of Sir James Bond, which is blown up at the start of the film.[13] Much of the filming for M's Scottish castle was actually done on location in County Meath, Ireland, with Killeen Castle, Dunsany, as the focus.[14] However, the car chase sequences where Bond leaves the castle were shot in the Perthshire village of Killin[15] with further sequences in Berkshire (specifically Old Windsor and Bracknell).[16]

The production proved to be rather troubled, with five different directors helming different segments of the film and with stunt co-ordinator Richard Talmadge co-directing the final sequence. In addition to the credited writers, Woody Allen, Peter Sellers, Val Guest, Ben Hecht, Joseph Heller, Terry Southern, and Billy Wilder are all believed to have contributed to the screenplay to varying degrees. Val Guest was given the responsibility of splicing the various "chapters" together, and was offered the unique title of "Co-ordinating Director" but declined, claiming the chaotic plot would not reflect well on him if he were so credited. His extra credit was labelled "Additional Sequences" instead.[17]

Part of the behind-the-scenes drama of this film's production concerned the filming of the segments involving Peter Sellers. Screenwriter Wolf Mankowitz declared that Sellers felt intimidated by Orson Welles to the extent that, except for a couple of shots, neither was in the studio simultaneously. Other versions of the legend depict the drama stemming from Sellers being slighted, in favour of Welles, by Princess Margaret (whom Sellers knew) during her visit to the set. Welles also insisted on performing magic tricks as Le Chiffre, and the director obliged. Director Val Guest wrote that Welles did not think much of Sellers, and had refused to work with "that amateur". Director Joseph McGrath, a personal friend of Sellers, was punched by the actor when he complained about Sellers' behavior on the set.[18]

Some biographies of Sellers suggest that he took the role of Bond to heart, and was annoyed at the decision to make Casino Royale a comedy, as he wanted to play Bond straight. This is illustrated in somewhat fictionalised form in the film The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, based on the biography by Roger Lewis, who has claimed that Sellers kept re-writing and improvising scenes to make them play seriously. This story is in agreement with the observation that the only parts of the film close to the book are the ones featuring Sellers and Welles.[19] In the end, Sellers' involvement with the film was cut abruptly short.

Jean-Paul Belmondo and George Raft received major billing, even though both actors appear only briefly. Both appear during the climactic brawl at the end, Raft flipping his trademark coin and promptly shooting himself dead with a backwards-firing pistol, while Belmondo appears wearing a fake moustache as the French Foreign Legion officer who requires an English phrase book to translate "merde!" into "ooch!" during his fistfight.[1] Raft's coin flip, which originally appeared in Scarface (1932), had been spoofed a few years earlier in Some Like It Hot (1959).[20]

At the Intercon science fiction convention held in Slough in 1978, David Prowse commented on his part in this film, apparently his big-screen debut. He claimed that he was originally asked to play "Super Pooh", a giant Winnie-the-Pooh in a superhero costume who attacks Tremble during the Torture of The Mind sequence. This idea, as with many others in the film's script, was rapidly dropped, and Prowse was re-cast as a Frankenstein-type Monster for the closing scenes. The final sequence was principally directed by former actor and stuntman Richard Talmadge.[11]

The story of Casino Royale is told in an episodic format. Val Guest oversaw the assembly of the sections, although he turned down the credit of "co-ordinating director".[17]

Director credits:[21]

- Val Guest (additional sequences; scenes with Woody Allen and additional scenes with David Niven)

- Ken Hughes (Berlin scenes)

- John Huston (scenes at Sir James Bond's house and scenes at Scottish castle)

- Joseph McGrath (scenes with Peter Sellers, Ursula Andress and Orson Welles)

- Robert Parrish (some casino scenes with Peter Sellers and Orson Welles)

- Richard Talmadge (second unit)

Unfinished scenes

Sellers left the production before all his scenes were shot, which is why his character, Tremble, is so abruptly captured in the film. Whether Sellers was fired or simply walked off is unclear. Given that he often went absent for days at a time and was involved in conflicts with Welles, either explanation is plausible.[19] Regardless, Sellers was unavailable for the filming of an ending and of linking footage to explain the details, leaving the filmmakers to devise a way to make the existing footage work without him. The framing device of a beginning and ending with David Niven was invented to salvage the footage.[11] Val Guest said that he was given the task of creating a narrative thread which would link all segments of the film. He chose to use the original Bond and Vesper as linking characters to tie the story together. In the originally released versions of the film, a cardboard cutout of Sellers in the background was used for the final scenes. In later versions, this cardboard cutout was replaced by footage of Sellers in highland dress, inserted by "trick photography".

Signs of missing footage from the Sellers segments are evident at various points. Evelyn Tremble is not captured on camera; an outtake of Sellers entering a racing car was substituted. In this outtake, he calls for the car, à la Pink Panther, to chase down Vesper and her kidnappers; the next thing that is shown is Tremble being tortured. Out-takes of Sellers were also used for Tremble's dream sequence (pretending to play the piano on Ursula Andress' torso), in the finale - blowing out the candles whilst in highland dress - and at the end of the film when all the various "James Bond doubles" are together. In the kidnap sequence, Tremble's death is also very abruptly inserted; it consists of pre-existing footage of Tremble being rescued by Vesper, followed by a later-filmed shot of her abruptly deciding to shoot him, followed by a freeze-frame over some of the previous footage of her surrounded by bodies (noticeably a zoom-in on the previous shot).[11]

As well as this, an entire sequence involving Tremble going to the front for the underground James Bond training school (which turns out to be under Harrods, of which the training area was the lowest level) was never shot, thus creating an abrupt cut from Vesper announcing that Tremble will be James Bond to Tremble exiting the lift into the training school.

So many sequences from the film were removed, that several well-known actors never appeared in the final cut, including Ian Hendry (as 006, the agent whose body is briefly seen being disposed of by Vesper), Mona Washbourne and Arthur Mullard.[11]

Music

| Casino Royale | |

|---|---|

.png) | |

| Soundtrack album by Burt Bacharach, Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass and Dusty Springfield | |

| Released | 1967 |

| Recorded | 1967 |

| Length | 34:27 |

| Label | Colgems |

For the music, Feldman decided to bring Burt Bacharach, who had done the score for his previous production What's New Pussycat?. Bacharach worked over two years writing for Casino Royale, in the meantime composing the After the Fox score and being forced to decline participation in Luv. Lyricist Hal David contributed with various songs, many of which appeared in just instrumental versions.[22] Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass performed some of the songs with Mike Redway singing the lyrics to the title song as the end credits rolled. The title theme was Alpert's second number one on the Easy Listening chart where it spent two weeks at the top in June 1967 and peaked at number 27 on the Billboard Hot 100.[23]

The fourth chapter of the film features the song "The Look of Love" performed by Dusty Springfield. It is played in the scene of Vesper Lynd recruiting Evelyn Tremble, seen through a man-size aquarium in a seductive walk. "The Look of Love" was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Song. The song was a Top 10 radio hit at the KGB and KHJ radio stations. It was heard again in the first Austin Powers film, which was to a degree inspired by Casino Royale.[22] For the European release, Mireille Mathieu sang versions of "The Look of Love" in both French ("Les Yeux D'Amour"),[24] and German ("Ein Blick von Dir").[25]

Bacharach would later rework two tracks of the score into songs: "Home James, Don't Spare the Horses" was re-arranged as "Bond Street", appearing on Bacharach's album Reach Out (1967), and "Flying Saucer – First Stop Berlin", was reworked with vocals as "Let the Love Come Through" by orchestra leader and arranger Roland Shaw. A clarinet melody would later be featured in a Cracker Jack commercial. As an in-joke, a brief snippet of John Barry's song "Born Free" is used in the film. At the time, Barry was the main composer for the Eon Bond series, and said song won an Academy Award over Bacharach's own "Alfie".[26]

The original album cover art was done by Robert McGinnis, based on the film poster and the original stereo vinyl release of the soundtrack (Colgems #COSO-5005) is still highly sought after by audiophiles. It has been regarded by some music critics as the finest-sounding LP of all time.[27][28] The original LP was later issued by Varèse Sarabande in the same track order as shown below:

Soundtrack listing

- "Casino Royale Theme" – Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass

- "The Look of Love" – Dusty Springfield

- "Money Penny Goes for Broke"

- "Le Chiffre's Torture of the Mind"

- "Home James, Don't Spare the Horses"

- "Sir James' Trip to Find Mata"

- "The Look of Love" (Instrumental)

- "Hi There Miss Goodthighs"

- "Little French Boy"

- "Flying Saucer – First Stop Berlin"

- "The Venerable Sir James Bond"

- "Dream on James, You're Winning"

- "The Big Cowboys and Indians Fight at Casino Royale" / "Casino Royale Theme" (reprise)

The soundtrack album became famous among audio purists for the excellence of its recording. It then became a standard "audiophile test" record for decades to come, especially the vocal performance by Dusty Springfield on "The Look of Love."[29]

The film soundtrack has since been released by other companies in different configurations (including complete score releases).

Budget

The studio approved the film's production budget of $6 million, already quite large in 1966. However, during filming the project ran into several problems and the shoot ran months over schedule, with the costs also running well over. When the film was finally completed it had doubled its original budget. The final production budget of $12 million made it one of the most expensive films that had been made to that point. The previous Eon Bond film, Thunderball (1965), had a budget of $11 million while the nearly contemporary You Only Live Twice (1967), had a budget of $9.5 million.[30] The extremely high budget of Casino Royale led to comparisons with a troubled production from 1963, and it was referred to as "a runaway mini-Cleopatra".[31] Columbia at first announced the film was due to be released in time for Christmas 1966. The problems postponed the launch until April 1967.[11]

Release and reception

Casino Royale had its world premiere in London's Odeon Leicester Square on 13 April 1967, breaking many opening records in the theatre's history.[32] Its American premiere was held in New York on 28 April, at the Capitol and Cinema I theatres.[33] It opened two months prior to the fifth Bond film by Eon Productions, You Only Live Twice.[11]

Box office and marketing

Despite the lukewarm nature of the contemporary reviews, the pull of the James Bond name was sufficient to make it the 13th highest-grossing film in North America in 1967 with a gross of $22.7 million and a worldwide total of $41.7 million[34] ($296 million in 2016 dollars[5]).[lower-alpha 1] Orson Welles attributed the success of the film to a marketing strategy that featured a naked tattooed woman on the film's posters and print ads[1] as well as a billboard in New York's Times Square.[36] The campaign also included a series of commercials featuring British model Twiggy.[37] As late as 2011, the film was still making money for the estate of Peter Sellers, who negotiated an extraordinary 3% of the gross profits (an estimated £120 million), with the proceeds currently going to Cassie Unger, the daughter and sole heir of Sellers' beneficiary, fourth wife Lynne Frederick.[38]

Critical reception

No advance press screenings of Casino Royale were held, leading reviews to only appear after the premiere.[32] The chaotic nature of the production was featured heavily in contemporary reviews, while later reviewers have sometimes been kinder towards this. Roger Ebert said "This is possibly the most indulgent film ever made",[39] Time described Casino Royale as "an incoherent and vulgar vaudeville",[40] and Variety declared the film to be "a conglomeration of frenzied situations, ‘in’ gags and special effects, lacking discipline and cohesion."[41] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times had some positive statements about the film, considering Casino Royale had "more of the talent agent than the secret agent" and praising the "fast start" and the scenes up to the baccarat game between Bond and Le Chiffre. Afterwards, Crowther felt, the script became tiresome, repetitive and filled with clichés due to "wild and haphazard injections of 'in' jokes and outlandish gags", leading to an excessive length that made the film a "reckless, disconnected nonsense that could be telescoped or stopped at any point".[42]

Since its release the film has been widely criticised by a number of people. The film currently holds a 29% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 34 reviews with the consensus stating: "A goofy, dated parody of spy movie cliches, Casino Royale squanders its all-star cast on a meandering, mostly laugh-free script."[43] For instance, Simon Winder called Casino Royale "a pitiful spoof",[44] while Robert Druce described it as "an abstraction of real life".[45] In his review of the film, Leonard Maltin remarked, "Money, money everywhere, but [the] film is terribly uneven – sometimes funny, often not."[46]

Some later reviewers have been more impressed by the film. Andrea LeVasseur, in the AllMovie review, called it "the original ultimate spy spoof", and opined that the "nearly impossible to follow" plot made it "a satire to the highest degree". Further describing it as a "hideous, zany disaster" LeVasseur concluded that it was "a psychedelic, absurd masterpiece".[47] Cinema historian Robert von Dassanowsky has written about the artistic merits of the film and says "like Casablanca, Casino Royale is a film of momentary vision, collaboration, adaption, pastiche, and accident. It is the anti-auteur work of all time, a film shaped by the very zeitgeist it took on."[31] Romano Tozzi complimented the acting and humour, although he also mentioned that the film has several dull stretches.[48]

Writing in 1986, Danny Peary noted, "It's hard to believe that in 1967 we actually waited in anticipation for this so-called James Bond spoof. It was a disappointment then; it's a curio today, but just as hard to get through." Peary described the film as being "disjointed and stylistically erratic" and "a testament to wastefulness in the bigger-is-better cinema," before adding, "It would have been a good idea to cut the picture drastically, perhaps down to the scenes featuring Peter Sellers and Woody Allen. In fact, I recommend you see it on television when it's in a two-hour (including commercials) slot. Then you won't expect it to make any sense."[49]

Accolades

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[50]

Home video and film rights

Columbia Pictures released Casino Royale on VHS in 1989,[51] and on Laserdisc in 1994.[52] In 1997, following the Columbia/MGM/Kevin McClory lawsuit on ownership of the Bond film series, the rights to the film reverted to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (whose sister company United Artists co-owns the Bond film franchise) as a condition of the settlement.[53] MGM then issued the first DVD release of Casino Royale in 2002,[54] followed by a 40th anniversary special edition in 2007.[55][56]

Years later, as a result of the Sony/Comcast acquisition of MGM, Columbia would once again become responsible for the co-distribution of this film as well as the entire Eon Bond series, including the 2006 adaptation of Casino Royale. However, MGM Home Entertainment changed its distributor to 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment in May 2006. Fox has since been responsible for the debut of the 1967 Casino Royale on Blu-ray disc in 2011. Danjaq LLC, Eon's holding company, is shown as one of its present copyright owners.[56]

Alongside six other MGM-owned films, the studio posted Casino Royale on YouTube.[57]

See also

References

Explanatory notes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Girls of Casino Royale". Playboy., February 1967

- ↑ DVD audio commentary, Region 1, with film historians Steven Jay Rubin and John Cork. Bisset, after playing the casino extra in early footage, was cast again as Miss Goodthighs.

- ↑ McFarlane, Brian (2005). The Encyclopedia of British Film. Methuen Publishing. p. 412. ISBN 978-0-413-77526-9.

- ↑ Benson 1988, p. 11.

- 1 2 Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Duns, Jeremy (2 March 2011). "Casino Royale: discovering the lost script". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 56.

- ↑ Broccoli, Albert R.; Zec, Donald (1998). When the Snow Melts: The Autobiography of Cubby Broccoli. Boxtree. p. 199. ISBN 0752211625.

- ↑ McCarthy, Todd (2007). Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood. Grove Press. pp. 595, 629. ISBN 0802196403.

- ↑ p. 62 Sellers, Robert Sean Connery: A Celebration Robert Hale, 1 December 1999

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bassinger, Stuart. "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad Royale". Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ Gerber, Gail & Lisanti, Tom. Trippin' with Terry Southern: What I Think I Remember, McFarland, p. 48.

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Casino Royal Film Focus".

- ↑ "Casino Royale". British-Film-Locations.com. 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Casino Royale". Scotland: the Movie Location Guide. 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ http://www.britmovie.co.uk/forums/film-locations/115229-sixties-casino-royale-car-chase-locations-2.html

- 1 2 Guest, Val. So you want to be in Pictures, Reynolds & Hearn, 2001, ISBN 1-903111-15-3

- ↑ Sikov, Ed. Mr Strangelove: A Biography of Peter Sellers. Pan Macmillan, 2011. ISBN 1447207149. pp. 310-3

- 1 2 Lewis, Roger. The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, Applause Books, 2000, ISBN 1-55783-248-X

- ↑ Smith, Jim (2004). Gangster Films. Virgin Books. p. 34. ISBN 0753508389.

- ↑ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 63.

- 1 2 Burlingame, Jon (2012). "5: Casino Royale (1967)". The Music of James Bond. Oxford University Press. pp. 60–70. ISBN 0199986762.

- ↑ Whitburn, Joel (2002). Top Adult Contemporary: 1961–2001. Record Research. p. 19.

- ↑ Mike Hennessay, Mike (30 September 1967). "Paris". Billboard. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Mireille Mathieu gagne son procès". Le Figaro. 7 December 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ↑ Burt Bacharach, Song by Song: The Ultimate Burt Bacharach Reference for Fans

- ↑ Stachler, Joe. "Joe Stachler on Casino Royale's Great Soundtrack". Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- ↑ Panek, Richard (28 July 1991). "'Casino Royale' Is an LP Bond with a Gilt Edge". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- ↑ Panek, Richard (28 July 1991). "'Casino Royale' Is an LP Bond With a Gilt Edge". New York Times. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Debrug, Peter (15 June 2012). "Review: 'Revisiting 1967's 'Casino Royale". Variety. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- 1 2 von Dassanowsky, Robert (31 March 2010). "Casino Royale at 33: The Postmodern Epic in Spite of Itself". Bright Lights Film Journal. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- 1 2 Fox, Julian (1996). Woody: movies from Manhattan. B.T. Batsford. p. 39. ISBN 0713480297.

- ↑ "'Casino Royale' Kicks Off Today All Over Country". Film Daily. 28 April 1967.

- ↑ "Casino Royale – Box Office Data, Movie News, Cast Information". The numbers. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ↑ "Big Rental Films of 1967", Variety, 3 January 1968 p 25.

- ↑ flickr.com/photos/lonegroover/1152017497

- ↑ Pelegrine, Louis (27 April 1967). "Twiggy Plays Role In 'Casino' Campaign". Film Daily.

- ↑ Hardcastle, Ephraim (21 October 2011). "Money still rolling in from Peter Sellers's James Bond spoof Casino Royale". Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers Ltd. Daily Mail, The Mail on Sunday & Metro Media Group. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (1 May 1967). "Casino Royale". The Chicago Sun-Times (review). Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ↑ "Keystone Cop-Out". Time. 12 May 1967.

- ↑ "Casino Royale". Variety (review). May 1967. Retrieved 29 May 2007..

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (29 April 1967). "Casino Royale (1967)". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ "Casino Royale (1967)". = Rotten Tomatoes..

- ↑ The Man Who Saved Britain: A... Books. Google. 2007. ISBN 978-0-312-42666-8. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ↑ This day our daily fictions: an... Books. Google. 21 March 2007. ISBN 978-90-5183-401-7. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ↑ Maltin, Leonard (2008). "2009 Movie Guide". Plume: 219.

- ↑ Blaise, Judd. "Casino Royale > Overview". AllMovie. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ↑ Tozzi, Romano (1971). "John Huston". Falcon: 130. ISBN 0-900123-21-4..

- ↑ Peary, Danny (1986). "Guide for the Film Fanatic". Simon & Schuster: 84. ISBN 0671610813.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Bowker's Complete Video Directory 1994. New York: R.R. Bowker. 1994. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-8352-3391-0.

- ↑ "Casino Royale (1967)". Laserdisc Database. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Sterngold, James (30 March 1999). "Sony Pictures, in an accord with MGM, drops its plan to produce new James Bond movies". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ↑ Jacobson, Colin (11 March 2009). "Casino Royale (1967)". DVD Movie Guide. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ McCutcheon, David (25 July 2008). "CASINO ROYALE SPOOFS UP DVD". IGN. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- 1 2 Reuben, Michael (12 May 2011). "Casino Royale Blu-ray". Blu-Ray.com. Retrieved 26 January 2015..

- ↑ "YouTube to stream Hollywood films". BBC. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

Bibliography

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85283-233-9.

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. London: Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Casino Royale (1967 film). |

- Casino Royale at the Internet Movie Database

- Casino Royale at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

- Casino Royale at Le Film Guide

- "Casino royale" (complete dialogue).

- "Agony booth" (film recap).

- Casino Royale: "It's Too Much for One James Bond" (M Richardson) @ The Nice Rooms ezine