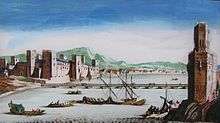

Castle of San Jorge

The Castle of San Jorge was a medieval fortress built on the west bank of the Guadalquivir River, inside the city of Seville (Spain), which was also used as a headquarters and prison for the Spanish Inquisition. It was demolished in the 19th century to build a food market. Currently in the underground ruins exists a museum centered on the Castle, the Spanish Inquisition and religious repression. Located in Barrio de Triana, next to the food market, is the Alley of the Inquisition, which was part of the fortification, and now connects Castilla Street with the Nuestra Señora de la O Walk.

History

The Visigoths created a fortification in the area next to the river to defend Spalis, the Visigothic name for Seville. During the Almohad domain in 1171, Jucef Abu Jacub, king of Isbilia, ordered the construction of the Puente de barcas (Bridge of Boats), a floating bridge over a row of boats, to unite the East and West shores.[1] The chains of that bridge would be linked to the then called Castle of Gabir. In the same year, the king funneled water from the Guadalquivir from the Castle to the inner city, spending a huge sum of money.[1] Ferdinand III of Castile, with the help of the fleet of Ramón de Bonifaz, broke the chains and with it, the bridge's barrier. This would help Ferdinand III to take the city in 1248. Up until 1280, the castle belonged to the Military Order of Saint George of Alfama, patron of knights and soldiers.

From Castle of Triana to Castle of San Jorge

In 1246, Seville and Granada were the only major cities in the Iberian Peninsula that had not fallen to Christian rule. During the summer of 1247, Castilian isolated Seville to the north and east. This paved the way for the siege, which started when Ramón de Bonifaz sailed with thirteen galleys, and some smaller ships, up the Guadalquivir and scattered his opposition. On May 3, the Castilian fleet broke the pontoon bridge linking Seville and Triana.[2]

Due to the subsequent famine the Muslims had no choice but to surrender. The city capitulated on November 23, 1248. They signed Ferdinand III's requirements under which they should leave the "whole" city with its buildings and land “libre et quita.”. The terms also specified that the Castillian troops would be allowed to enter the alcázar no later than a month later. During that time, the city was prepared to be occupied, mosques were purified (so these could become Christian temples) as well as the places where the Christian armies would settle; they reserved the best houses for the lords and chiefs. Once this term was over, the Moorish king Axataf handed the keys of the city to King Ferdinand. The city was then empty for three days. Ferdinand made his triumphant entry into the city on December 22, 1248.

Finished taking possession of the city, they proceeded to distribute things in the same way as before, according to Castilian laws, customs and uses of the time. It was understood that a conquered city belonged to the conqueror, and in this case to the crown, by "right of conquest." The distribution was made between members of the royal family, princes, bishops, knights, rich men, military orders, religious orders, good men and laborers; all those who had taken part in the success. Military orders received houses and properties located all within the city walls, with the exception of the Order of St. George of Alfama, whose knights were given the Castle of Triana. Triana was named “Guarda de Sevilla” (Guardian of Seville).[[File:Batalla del Puig, San Jorge y Jaime I de Aragón.jpg|thumb|left|upright|

The Order of St. George of Alfama was not a military order in the style of the Orders already established, like the Temple, the Hospitaller, Calatrava and Santiago born in the heat of the Reconquista (Reconquest), and whose primary purpose of defending Christianity was the attack of the infidels. The Order of St. George had more modest aims: to defend against the Saracens in the coastal zone, and the zone's repopulation. The King considered that a bank is a coast of a river, and that to guard the banks of the Guadalquivir fitted the Rule of this Order; and so he gave them the castle, renamed the Castle of San Jorge, as his part in the deal.

Among the activities at the castle was the veneration of their patron (Saint George) through cults and religious celebrations, for which rose a chapel that over the years became the first parish of Triana. That is, the temple of St. George's parish was none other than the knights' chapel inside the castle. This is also the origin of the trianera devotion to St. George.

However, the people of the thirteenth century did not feel very attracted to this Order, whose task was to defend the coast. They did not consider this a prestigious activity, especially when other Militias like Malta, Calatrava or the Temple were given the opportunity to enjoy broad military glory and immunities. Therefore, the Order of St. George of Alfama led a nondescript life for more than a century.[3]

According to the chronicles, although their knights were men of well-proven value in war, they led a somewhat relaxed life in peaceful times.

In 1400, the Order of St. George of Alfama disappeared, and was absorbed by the powerful Order of Montesa.

This, and that the importance of the castle as a defensive element decreased over the years, explains why during the second half of the 15th century the Castle of San Jorge experienced a period of neglect.

The abandoned castle was delivered in 1481 to the newly created Inquisition, who used it as a headquarters and prison.

Headquarters of the Court of the Inquisition

When the Inquisition began in Seville, they began to need more space for their dungeons. Since the Castle of San Jorge was unused, it was a very apparent place for those duties and it ceded to it the Court.

The Inquisition originally came up with the intention of suppressing heresy within the Catholic Church itself, ensuring its spiritual purity. But the "Modern Inquisition" (which was established in Seville), contrary to what is believed, was an independent institution of the Church, to prosecute false Christians and heretics.

It was created by the Catholic Monarchs and began operating in Seville in 1481, with the converts strongly opposed to the establishment of the Court.

The thing was, being that Seville as was an amalgam of cultures, with remarkable Judeo-Moorish minorities and a large commercial center open to traffic of all nations, it was an ideal place for the presence and distribution of non-Catholic ideologies.

It was an archbishop of Seville, Pedro González de Mendoza, that was the true founder of the Modern Inquisition. The Christians accused of heresy were forbidden to appeal to Rome, so that the "religious control" became independent controlled outside the papal curia.

The Tribunal of the Holy Office began with its headquarters at the convent of San Pablo of the Dominicans (present church of la Magdalena) who, because of the rivalry that it maintained with the Franciscan Order, and risking its prestige, had no problem in turning their convent into a temporary prison for the men and women "most guilty" of heresy. However, it soon had to move to the Castle of San Jorge where there was more rrom for the dungeons, where the judges and officers "of this holy office" lived.

However, given the direction that the inquisitorial bureaucracy was taking, it did not have much space in the castle: due to the fact that two of the inquisitors had harsh differences and there were jealousies caused by the one-man office of one of the notaries.

The essential work of the Holy Office was to pursue and prosecute the false converts.

The real inquisition was held at the Castle of San Jorge: it was where the inmates were kept, where the Court subjected them to "interrogation," and where they awaited execution and sentencing. Instead, the sentenced were held in so-called "life imprisonment" that was in El Salvador.[4]

The jail was unhealthy, both wet or hot, to a greater or lesser extent depending on the cell's floor. The secret prisons were divided into high and low cells.

The Castle of San Jorge was a feared and hated place among other things, because its walls served as shelter to criminals who had committed a crime, but as they were friends or relatives of the Inquisition, enjoyed immunity.

Also the Inquisition had collaboration of the "familiars," a kind of police who enjoyed the privileges of escaping the jurisdiction of other courts, and were also authorized to carry weapons.

Although expressly prohibited such excesses, the "servants of the Inquisition" and the "right of asylum" continued to commit crimes under the pretext of immunity.

The Auto-da-fés that were held in Seville took place first on the steps of the Cathedral, and then in the Plaza de San Francisco, although many of them occurred in the Church of Santa Ana.

On the other hand, the Auto-da-fés were considered a party by the people, and a large crowd came that used to participate in an angry way around the complicated ceremony.

According to Giorgio Vasari, the Florentine artist Pietro Torrigiano was arrested by the Inquisition, and died in the Castle of San Jorge in 1522 in a kind of hunger strike, although it is possible that this story is apocryphal.

The Inquisition left the castle in 1626, due to the continued deterioration of its walls due to of heavy flooding. After that, it was loaned to the Count-Duke of Olivares, in which he dealt with its repairs and care, and the surveillance of goods carried to its doorstep.

Later given to the city, City Hall demolished the castle in the 19th century. It was destroyed to widen the space to connect the Altozano with Castilla street and to create a grain warehouse.

Around 1830, on the occasion of the traveling market that spontaneously formed in its surroundings, a food market was built that continues today.

The Alley of the Inquisition (Callejón de la Inquisición), located at the confluence of the Castilla, San Jorge y Callao streets, is evidence of the presence of the old inquisitorial court in Triana.

The Castle today

In 1823 the Mercado de Triana was built on the site of the castle, which remains in operation today. Beneath the market numerous archaeological excavations were carried out, which concluded that the remains should be in a museum. In 2009 the City Hall of Seville inaugurated the Castillo de San Jorge project, thus creating an interpretation center for the ruins and the religious repression that the Spanish Inquisition conducted.

Scenario of Fidelio by Beethoven

In 1805, Ludwig van Beethoven premiered his opera Fidelio about a Sevillian prison which held prisoners of conscience in the late-18th century. While he didn't specifically name it in the text, it is very likely that the composer meant the castle of San Jorge. In recent years, Seville has attempted to monetize its operatic past with an inititave called Sevilla Ciudad de Ópera (Seville City of Opera). This has included Castle tours about the operatic heritage of Seville, and a commemorative plaque installed at the site.

References

- 1 2 Flores, Leandro J. (1833). Memorias historicas de la villa de Alcalá de Guadaira: Desde sus primeros pobladores hasta la conquista y repartimiento por San Fernando, Volumen 1 [Historical memoirs of the villa of Alcalá de Guadaira, Volume 1] (in Spanish).

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (2004). Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. pp. 113–116. ISBN 978-0-8122-1889-3. Check

|isbn=value: invalid character (help). - ↑ "De Castillo de Triana a Castillo de San Jorge", eldiariodetriana.es

- ↑ "De Castillo de San Jorge a Tribunal de la Inquisición", eldiariodetriana.es

External links

Coordinates: 37°23′09″N 6°00′12″W / 37.3858°N 6.0033°W