Spanish Inquisition

| Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Spain Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición Spanish Inquisition | |

|---|---|

Seal for the Tribunal in Spain. | |

| Type | |

| Type |

Tribunal under the election of the Spanish monarchy, for upholding religious orthodoxy in their realm |

| History | |

| Established | 1 November 1478 |

| Disbanded | 15 July 1834 |

| Seats | Consisted of a Grand Inquisitor, who headed the Council of the Supreme and General Inquisition, made up of six members. Under it were up to 21 tribunals in the empire. |

| Elections | |

| Grand Inquisitor and Suprema designated by the crown | |

| Meeting place | |

| Spanish Empire | |

| Footnotes | |

|

See also: Medieval Inquisition Portuguese Inquisition Mexican Inquisition | |

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition (Spanish: Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition (Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. It was intended to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms and to replace the Medieval Inquisition, which was under Papal control. It became the most substantive of the three different manifestations of the wider Christian Inquisition along with the Roman Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition. The "Spanish Inquisition" may be defined broadly, operating "in Spain and in all Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Spanish Netherlands, the Kingdom of Naples, and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America."

The Inquisition was originally intended primarily to ensure the orthodoxy of those who converted from Judaism and Islam. The regulation of the faith of the newly converted was intensified after the royal decrees issued in 1492 and 1502 ordering Jews and Muslims to convert or leave Spain.[1] The Inquisition was not definitively abolished until 1834, during the reign of Isabella II, after a period of declining influence in the preceding century.

The Spanish Inquisition is often stated in popular literature and history as an example of Catholic intolerance and repression. Modern historians have tended to question earlier accounts concerning the severity of the Inquisition. Henry Kamen asserts that the 'myth' of the all-powerful, torture-mad inquisition is largely an invention of nineteenth century Protestant authors with an agenda to discredit the Papacy.[2] Although records are incomplete, about 150,000 persons were charged with crimes by the Inquisition and about 3,000 were executed.

Previous inquisitions

The Inquisition was created through papal bull, Ad Abolendam, issued at the end of the twelfth century by Pope Lucius III as a way to combat the Albigensian heresy in southern France. There were a huge number of tribunals of the Papal Inquisition in various European kingdoms during the Middle Ages. In the Kingdom of Aragon, a tribunal of the Papal Inquisition was established by the statute of Excommunicamus of Pope Gregory IX, in 1232, during the era of the Albigensian heresy. Although not an inquisitor, as canon lawyer and an advisor to James I of Aragon, Raymond of Penyafort was often consulted regarding questions of law regarding the practices of the Inquisition in the king's domains. "...[T]he lawyer's deep sense of justice and equity, combined with the worthy Dominican's sense of compassion, allowed him to steer clear of the excesses that were found elsewhere in the formative years of the inquisitions into heresy."[3] With time, its importance was diluted, and, by the middle of the fifteenth century, it was almost forgotten although still there according to the law.

There was never a tribunal of the Papal Inquisition in Castile. Members of the episcopate were charged with surveillance of the faithful and punishment of transgressors. During the Middle Ages, in Castile, little attention was paid to heresy by the Catholic ruling class. Jews and Muslims were tolerated and generally allowed to follow their traditional laws and customs in domestic matters. However, by law, they were considered inferior to Catholics and were subject to discriminatory legislation.

The Spanish Inquisition (Inquisición Española) can be seen as an answer to the multi-religious nature of Spanish society following the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslim Moors. After invading in 711, large areas of the Iberian Peninsula were ruled by Muslims until 1250, when they were restricted to Granada, which fell in 1492. However, the Reconquista did not result in the total expulsion of Muslims from Spain, since they, along with Jews, were tolerated by the ruling Christian elite. Large cities, especially Seville, Valladolid and Barcelona, had significant Jewish populations centered in Juderia, but in the coming years the Muslims were increasingly subjugated by alienation and torture. The Jews, who had previously thrived under Muslim rule, now suffered similar maltreatment.

Post-reconquest medieval Spain has been characterized by Americo Castro and some other Iberianists as a society of "convivencia", that is relatively peaceful co-existence, albeit punctuated by occasional conflict among the ruling Catholics and the Jews and Muslims. However, as Henry Kamen notes, "so-called convivencia was always a relationship between unequals."[4] Despite their legal inequality, there was a long tradition of Jewish service to the crown of Aragon and Jews occupied many important posts, both religious and political. Castile itself had an unofficial rabbi. Ferdinand's father John II named the Jewish Abiathar Crescas to be Court Astronomer.

Antisemitic attitudes increased all over Europe during the late 13th century and throughout the 14th century. England and France expelled their Jewish populations in 1290 and 1306 respectively.[5] At the same time, during the Reconquista, Spain's anti-Jewish sentiment steadily increased. This prejudice climaxed in the summer of 1391 when violent anti-Jewish riots broke out in Spanish cities like Barcelona[6] To linguistically distinguish them from non-converted or long-established Christian families, new converts were called conversos, or New Christians.

According to Don Hasdai Crescas, persecution against Jews began in earnest in Seville in 1391, on the 1st day of the lunar month Tammuz (June).[7] From there the violence spread to Córdoba, and by the 17th day of the same lunar month, it had reached Toledo (called then by Jews after its Arabic name "Ṭulayṭulah") in the region of Castile.[8] From there, the violence had spread to Majorca and by the 1st day of the lunar month Elul it had also reached the Jews of Barcelona in Catalonia, where the slain were estimated at two-hundred and fifty. So, too, many Jews who resided in the neighboring provinces of Lérida and Gironda and in the kingdom of València had been affected,[9] as were also the Jews of Al-Andalus (Andalucía),[10] whereas many died a martyr’s death, while others converted in order to save themselves.

Encouraged by the preaching of Ferrand Martinez, Archdeacon of Ecija, the general unrest affected nearly all of the Jews in Spain, during which time an estimated 200,000 Jews changed their religion or else concealed their religion, becoming known in Hebrew as "Anūsim,"[11] meaning, "those who are compelled [to hide their religion]." Only a handful of the more principal persons of the Jewish community managed to escape, who had found refuge among the viceroys in the outlying towns and districts.[7]

Forced baptism was contrary to the law of the Catholic Church, and theoretically anybody who had been forcibly baptized could legally return to Judaism. Legal definitions of the time theoretically acknowledged that a forced baptism was not a valid sacrament, but confined this to cases where it was literally administered by physical force: a person who had consented to baptism under threat of death or serious injury was still regarded as a voluntary convert, and accordingly forbidden to revert to Judaism.[12] After the public violence, many of the converted "felt it safer to remain in their new religion."[13] Thus, after 1391, a new social group appeared and were referred to as conversos or New Christians. Many conversos, now freed from the anti-Semitic restrictions imposed on Jewish employment, attained important positions in fifteenth century Spain, including positions in the government and in the Church. Among many others, physicians Andrés Laguna and Francisco Lopez Villalobos (Ferdinand's court physician), writers Juan del Enzina, Juan de Mena, Diego de Valera and Alonso de Palencia, and bankers Luis de Santangel and Gabriel Sanchez (who financed the voyage of Christopher Columbus) were all conversos. Conversos - not without opposition - managed to attain high positions in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, at times becoming severe detractors of Judaism.[14] Some even received titles of nobility, and as a result, during the following century some works attempted to demonstrate that virtually all of the nobles of Spain were descended from Israelites.[15]

Activity of the Inquisition

Start of the Inquisition

Fray Alonso de Ojeda, a Dominican friar from Seville, convinced Queen Isabella of the existence of Crypto-Judaism among Andalusian conversos during her stay in Seville between 1477 and 1478.[16] A report, produced by Pedro González de Mendoza, Archbishop of Seville, and by the Segovian Dominican Tomás de Torquemada, corroborated this assertion. In 1480 a plot to overthrow the government of Seville under armed insurrection led by Don Diego de Susona, a wealthy merchant converso was discovered and suppressed.[17][18]

Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella requested a papal bull establishing an inquisition in Spain in 1478 in response to the conversos returning to the practice of Judaism. Pope Sixtus IV granted a bull permitting the monarchs to select and appoint two or three priests over forty years of age to act as inquisitors.[19] In 1483, Ferdinand and Isabella established a state council to administer the inquisition with the Dominican Friar Tomás de Torquemada acting as its president, even though Sixtus IV protested the activities of the inquisition in Aragon and its treatment of the conversos. Torquemada eventually assumed the title of Inquisitor-General.[20]

Thomas Madden describes the world that formed medieval politics: "The Inquisition was not born out of desire to crush diversity or oppress people; it was rather an attempt to stop unjust executions. Yes, you read that correctly. Heresy was a crime against the state. Roman law in the Code of Justinian made it a capital offense. Rulers, whose authority was believed to come from God, had no patience for heretics".[21] The monarchs decided to introduce the Inquisition to Castile to discover and punish crypto-Jews, and requested the pope's assent. Ferdinand II of Aragon pressured Pope Sixtus IV to agree to an Inquisition controlled by the monarchy by threatening to withdraw military support at a time when the Turks were a threat to Rome. The pope issued a bull to stop the Inquisition but was pressured into withdrawing it. On 1 November 1478, Pope Sixtus IV published the Papal bull, Exigit Sinceras Devotionis Affectus, through which he gave the monarchs exclusive authority to name the inquisitors in their kingdoms. The first two inquisitors, Miguel de Morillo and Juan de San Martín, were not named, however, until two years later, on 27 September 1480 in Medina del Campo.

The first auto-da-fé was held in Seville on 6 February 1481: six people were burned alive. From there, the Inquisition grew rapidly in the Kingdom of Castile. By 1492, tribunals existed in eight Castilian cities: Ávila, Córdoba, Jaén, Medina del Campo, Segovia, Sigüenza, Toledo, and Valladolid. Sixtus IV promulgated a new bull categorically prohibiting the Inquisition's extension to Aragón, affirming that,

many true and faithful Christians, because of the testimony of enemies, rivals, slaves and other low people—and still less appropriate—without tests of any kind, have been locked up in secular prisons, tortured and condemned like relapsed heretics, deprived of their goods and properties, and given over to the secular arm to be executed, at great danger to their souls, giving a pernicious example and causing scandal to many.[22]

"In 1482 the pope was still trying to maintain control over the Inquisition and to gain acceptance for his own attitude towards the New Christians, which was generally more moderate than that of the Inquisition and the local rulers."[23]

In 1483, Jews were expelled from all of Andalusia. Though the pope wanted to crack down on abuses, Ferdinand pressured him to promulgate a new bull, threatening that he would otherwise separate the Inquisition from Church authority.[24][25] Sixtus did so on 17 October 1483, naming Tomás de Torquemada Inquisidor General of Aragón, Valencia, and Catalonia.

Torquemada quickly established procedures for the Inquisition. A new court would be announced with a thirty-day grace period for confessions and the gathering of accusations by neighbors. Evidence that was used to identify a crypto-Jew included the absence of chimney smoke on Saturdays (a sign the family might secretly be honoring the Sabbath) or the buying of many vegetables before Passover or the purchase of meat from a converted butcher. The court employed physical torture to extract confessions. Crypto-Jews were allowed to confess and do penance, although those who relapsed were burned at the stake.[26]

In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII attempted to allow appeals to Rome against the Inquisition, but Ferdinand in December 1484 and again in 1509 decreed death and confiscation for anyone trying to make use of such procedures without royal permission.[27] With this, the Inquisition became the only institution that held authority across all the realms of the Spanish monarchy and, in all of them, a useful mechanism at the service of the crown. However, the cities of Aragón continued resisting, and even saw revolt, as in Teruel from 1484 to 1485. However, the murder of Inquisidor Pedro Arbués in Zaragoza on September 15, 1485, caused public opinion to turn against the conversos and in favour of the Inquisition. In Aragón, the Inquisitorial courts were focused specifically on members of the powerful converso minority, ending their influence in the Aragonese administration.

The Inquisition was extremely active between 1480 and 1530. Different sources give different estimates of the number of trials and executions in this period; Henry Kamen estimates about 2,000 executed, based on the documentation of the autos-da-fé, the great majority being conversos of Jewish origin. He offers striking statistics: 91.6% of those judged in Valencia between 1484 and 1530 and 99.3% of those judged in Barcelona between 1484 and 1505 were of Jewish origin.[28]

Expulsion of Jews and repression of conversos

The Spanish Inquisition had been established in part to prevent conversos from engaging in Jewish practices, which, as Christians, they were supposed to have given up. However this remedy for securing the orthodoxy of conversos was eventually deemed inadequate since the main justification the monarchy gave for formally expelling all Jews from Spain was the "great harm suffered by Christians (i.e., conversos) from the contact, intercourse and communication which they have with the Jews, who always attempt in various ways to seduce faithful Christians from our Holy Catholic Faith".[29] The Alhambra Decree, issued in January 1492, ordered the expulsion. Historic accounts of the numbers of Jews who left Spain have been vastly exaggerated by early accounts and historians: Juan de Mariana speaks of 800,000 people, and Don Isaac Abravanel of 300,000. Modern estimates, based on careful examination of official documents and population estimates of communities, are much lower: Henry Kamen estimates that, of a population of approximately 80,000 Jews and 200,000 conversos, about 40,000 chose emigration.[30] The Jews of the kingdom of Castile emigrated mainly to Portugal (whence they were expelled in 1497) and to North Africa. However, according to Kamen, the Jews of the kingdom of Aragon went "to adjacent Christian lands, mainly to Italy", rather than to Muslim lands as is often assumed.[31] Although the vast majority of conversos simply assimilated into the Catholic dominant culture, a minority continued to practice Judaism in secret, gradually migrated throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, mainly to areas where Sephardic communities were already present as a result of the Alhambra Decree.[32]

Tens of thousands of Jews were baptised in the three months before the deadline for expulsion, some 40,000 if one accepts the totals given by Kamen, most of these undoubtedly to avoid expulsion, rather than as a sincere change of faith. These conversos were the principal concern of the Inquisition; being suspected of continuing to practice Judaism put them at risk of denunciation and trial.

The most intense period of persecution of conversos lasted until 1530. From 1531 to 1560, however, the percentage of conversos among the Inquisition trials dropped to 3% of the total. There was a rebound of persecutions when a group of crypto-Jews was discovered in Quintanar de la Orden in 1588; and there was a rise in denunciations of conversos in the last decade of the sixteenth century. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, some conversos who had fled to Portugal began to return to Spain, fleeing the persecution of the Portuguese Inquisition, founded in 1536. This led to a rapid increase in the trials of crypto-Jews, among them a number of important financiers. In 1691, during a number of autos-da-fé in Majorca, 37 chuetas, or conversos of Majorca, were burned.[33]

During the eighteenth century the number of conversos accused by the Inquisition decreased significantly. Manuel Santiago Vivar, tried in Córdoba in 1818, was the last person tried for being a crypto-Jew.[34]

Repression of Moriscos

The Inquisition searched for false converts from Judaism among the conversos, but also searched for false or relapsed converts among the Moriscos, forced converts from Islam. In spite of myth Kamen asserts that very few Protestants were involved.[35] Beginning with a decree on February 14, 1502, Muslims in Granada faced forcible conversion to Christianity or expulsion.[1] Muslims in the Crown of Aragon were obliged to convert by Charles I's decree of 1526, as most had been forcibly baptized during the Revolt of the Brotherhoods (1519–1523) and these baptisms were declared to be valid. The War of the Alpujarras between 1568-1571, a general Muslim/Morisco uprising in Granada, ended in a forced dispersal of about half of the region's Moriscos throughout Castile and Andalusia as well as increased suspicions by Spanish authorities against this community.

Many Moriscos were suspected of practising Islam in secret, and the jealousy with which they guarded the privacy of their domestic life prevented the verification of this suspicion.[36] Initially they were not severely persecuted by the Inquisition, but experienced a policy of evangelization without torture,[37] a policy not followed with those conversos who were suspected of being crypto-Jews. There were various reasons for this. Most importantly, in the kingdoms of Valencia and Aragon a large number of the Moriscos were under the jurisdiction of the nobility, and persecution would have been viewed as a frontal assault on the economic interests of this powerful social class.[38] Still, fears ran high among the population that the Moriscos were traitorous, especially in Granada. The coast was regularly raided by Barbary pirates backed by Spain's enemy the Ottoman Empire, and the Moriscos were suspected of aiding them.

In the second half of the century, late in the reign of Philip II, conditions worsened between Old Christians and Moriscos. The 1568–1570 Morisco Revolt in Granada was harshly suppressed, and the Inquisition intensified its attention to the Moriscos. From 1570 Morisco cases became predominant in the tribunals of Zaragoza, Valencia and Granada; in the tribunal of Granada, between 1560 and 1571, 82% of those accused were Moriscos, who were a vast majority of the Kingdom's population at the time.[39] Still, according to Kamen, the Moriscos did not experience the same harshness as judaizing conversos and Protestants, and the number of capital punishments was proportionally less.[40]

In 1609, King Philip III, upon the advice of his financial adviser the Duke of Lerma and Archbishop of Valencia Juan de Ribera, decreed the Expulsion of the Moriscos. Hundreds of thousands of Moriscos were expelled, some of them probably sincere Christians. This was further fueled by the religious intolerance of Archbishop Ribera who quoted the Old Testament texts ordering the enemies of God to be slain without mercy and setting forth the duties of kings to extirpate them.[41] The edict required: 'The Moriscos to depart, under the pain of death and confiscation, without trial or sentence... to take with them no money, bullion, jewels or bills of exchange.... just what they could carry.'[42] Although initial estimates of the number expelled such as those of Henri Lapeyre reach 300,000 Moriscos (or 4% of the total Spanish population), the extent and severity of the expulsion in much of Spain has been increasingly challenged by modern historians such as Trevor J. Dadson.[43] Nevertheless, the eastern region of Valencia, where ethnic tensions were high, was particularly affected by the expulsion, suffering economic collapse and depopulation of much of its territory.

Of those permanently expelled, the majority finally settled in the Maghreb or the Barbary coast.[44] Those who avoided expulsion or who managed to return were gradually absorbed by the dominant culture.[45]

The Inquisition pursued some trials against them of minor importance against Moriscos who remained or returned after expulsion: according to Kamen, between 1615 and 1700, cases against Moriscos constituted only 9 percent of those judged by the Inquisition. Upon the coronation of Philip IV in 1621, the new king gave the order to desist from attempting to impose measures on remaining Moriscos and returnees. In September 1628 the Council of the Supreme Inquisition ordered inquisitors in Seville not to prosecute expelled Moriscos "unless they cause significant commotion." [46] The last mass prosecution against Moriscos for crypto-Islamic practices occurred in Granada in 1727, with most of those convicted receiving relatively light sentences. By the end of the 18th century, the indigenous practice of Islam is considered to have been effectively extinguished in Spain.[47]

Control of Protestants

Despite much popular myth about the Spanish Inquisition relating to Protestants, it dealt with very few cases involving actual Protestants, as there were so few in Spain.[48] Lutheran was a portmanteau accusation used by the inquisition to act against all those who acted in a way which was offensive to the church. The first of the trials against those labeled by the Inquisition as "Lutheran" were those against the sect of mystics known as the "Alumbrados" of Guadalajara and Valladolid. The trials were long, and ended with prison sentences of differing lengths, though none of the sect were executed. Nevertheless, the subject of the "Alumbrados" put the Inquisition on the trail of many intellectuals and clerics who, interested in Erasmian ideas, had strayed from orthodoxy. This is striking because both Charles I and Philip II were confessed admirers of Erasmus.[49][50] Such was the case with the humanist Juan de Valdés,[51] who was forced to flee to Italy to escape the process that had been begun against him, and the preacher, Juan de Ávila, who spent close to a year in prison.[52]

The first trials against Lutheran groups, as such, took place between 1558 and 1562, at the beginning of the reign of Philip II, against two communities of Protestants from the cities of Valladolid and Seville numbering about 120.[53] The trials signaled a notable intensification of the Inquisition's activities. A number of autos-da-fé were held, some of them presided over by members of the royal family, and around 100 executions took place.[54] The autos-da-fé of the mid-century virtually put an end to Spanish Protestantism which was, throughout, a small phenomenon to begin with.[55]

After 1562, though the trials continued, the repression was much reduced. According to Kamen, about 200 Spaniards were accused of being Protestants in the last decades of the 16th century. "Most of them were in no sense Protestants...Irreligious sentiments, drunken mockery, anticlerical expressions, were all captiously classified by the inquisitors (or by those who denounced the cases) as 'Lutheran.' Disrespect to church images, and eating meat on forbidden days, were taken as signs of heresy"[56] and it is estimated that a dozen Spaniards were burned alive.[57]

Censorship

As one manifestation of the Counter-Reformation, the Spanish Inquisition worked actively to impede the diffusion of heretical ideas in Spain by producing "Indexes" of prohibited books. Such lists of prohibited books were common in Europe a decade before the Inquisition published its first. The first Index published in Spain in 1551 was, in reality, a reprinting of the Index published by the University of Leuven in 1550, with an appendix dedicated to Spanish texts. Subsequent Indexes were published in 1559, 1583, 1612, 1632, and 1640. The Indexes included an enormous number of books of all types, though special attention was dedicated to religious works, and, particularly, vernacular translations of the Bible.

Included in the Indexes, at one point, were many of the great works of Spanish literature. Also, a number of religious writers who are today considered saints by the Catholic Church saw their works appear in the Indexes. At first, this might seem counter-intuitive or even nonsensical—how were these Spanish authors published in the first place if their texts were then prohibited by the Inquisition and placed in the Index? The answer lies in the process of publication and censorship in Early Modern Spain. Books in Early Modern Spain faced prepublication licensing and approval (which could include modification) by both secular and religious authorities. However, once approved and published, the circulating text also faced the possibility of post-hoc censorship by being denounced to the Inquisition—sometimes decades later. Likewise, as Catholic theology evolved, once-prohibited texts might be removed from the Index.

At first, inclusion in the Index meant total prohibition of a text; however, this proved not only impractical and unworkable, but also contrary to the goals of having a literate and well-educated clergy. Works with one line of suspect dogma would be prohibited in their entirety, despite the remainder of the text's sound dogma. In time, a compromise solution was adopted in which trusted Inquisition officials blotted out words, lines or whole passages of otherwise acceptable texts, thus allowing these expurgated editions to circulate. Although in theory the Indexes imposed enormous restrictions on the diffusion of culture in Spain, some historians, such as Henry Kamen, argue that such strict control was impossible in practice and that there was much more liberty in this respect than is often believed. And Irving Leonard has conclusively demonstrated that, despite repeated royal prohibitions, romances of chivalry, such as Amadis of Gaul, found their way to the New World with the blessing of the Inquisition. Moreover, with the coming of the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century, increasing numbers of licenses to possess and read prohibited texts were granted.

Despite repeated publication of the Indexes and a large bureaucracy of censors, the activities of the Inquisition did not impede the flowering of Spanish literature's "Siglo de Oro", although almost all of its major authors crossed paths with the Holy Office at one point or another. Among the Spanish authors included in the Index are: Bartolomé Torres Naharro, Juan del Enzina, Jorge de Montemayor, Juan de Valdés and Lope de Vega, as well as the anonymous Lazarillo de Tormes and the Cancionero General by Hernando del Castillo. La Celestina, which was not included in the Indexes of the 16th century, was expurgated in 1632 and prohibited in its entirety in 1790. Among the non-Spanish authors prohibited were Ovid, Dante, Rabelais, Ariosto, Machiavelli, Erasmus, Jean Bodin, Valentine Naibod and Thomas More (known in Spain as Tomás Moro). One of the most outstanding and best-known cases in which the Inquisition directly confronted literary activity is that of Fray Luis de León, noted humanist and religious writer of converso origin, who was imprisoned for four years (from 1572 to 1576) for having translated the Song of Songs directly from Hebrew.

Some scholars state that one of the main effects of the inquisition was to end free thought and scientific thought in Spain. As one contemporary Spaniard in exile put it: "Our country is a land of ... barbarism; down there one cannot produce any culture without being suspected of heresy, error and Judaism. Thus silence was imposed on the learned." For the next few centuries, while the rest of Europe was slowly awakened by the influence of the Enlightenment, Spain stagnated.[58] However, this conclusion is contested.

The censorship of books was actually very ineffective, and prohibited books circulated in Spain without significant problems. The Spanish Inquisition never persecuted scientists, and relatively few scientific books were placed on the Index. On the other hand, Spain was a state with more political freedom than in other absolute monarchies in the 16th to 18th centuries. The backwardness of Spain in economy and science may not be attributable to the Inquisition.[59]

Suppression of other heresies

Witchcraft

The category "superstitions" includes trials related to witchcraft. The witch-hunt in Spain had much less intensity than in other European countries (particularly France, Scotland, and Germany). One remarkable case was that of Logroño, in which the witches of Zugarramurdi in Navarre were persecuted. During the auto-da-fé that took place in Logroño on November 7 and November 8, 1610, 6 people were burned and another 5 burned in effigy.[60] The role of the inquisition in cases of witchcraft was much more restricted than is commonly believed. Well after the foundation of the inquisition, jurisdiction over sorcery and witchcraft remained in secular hands.[61] In general the Inquisition maintained a skeptical attitude towards cases of witchcraft, considering it as a mere superstition without any basis. Alonso de Salazar Frías, who, after the trials of Logroño took the Edict of Faith to various parts of Navarre, noted in his report to the Suprema that, "There were neither witches nor bewitched in a village until they were talked and written about".[62]

Blasphemy

Included under the rubric of heretical propositions were verbal offences, from outright blasphemy to questionable statements regarding religious beliefs, from issues of sexual morality, to misbehaviour of the clergy. Many were brought to trial for affirming that simple fornication (sex between unmarried persons) was not a sin or for putting in doubt different aspects of Christian faith such as Transubstantiation or the virginity of Mary.[63] Also, members of the clergy itself were occasionally accused of heretical propositions. These offences rarely led to severe penalties.

Bigamy

The Inquisition also pursued offences against morals, at times in open conflict with the jurisdictions of civil tribunals. In particular, there were trials for bigamy, a relatively frequent offence[64] in a society that only permitted divorce under the most extreme circumstances. In the case of men, the penalty was five years service as an oarsman in a royal galley[65] (possibly a death sentence).[66] Women too were accused of bigamy. Also, many cases of solicitation during confession were adjudicated, indicating a strict vigilance over the clergy.

Sodomy and rape

The first sodomite was burned by the Inquisition in Valencia in 1572, and those accused included 19% clergy, 6% nobles, 37% workers, 19% servants, and 18% soldiers and sailors.[67]

Nearly all of almost 500 cases of sodomy between persons concerned the relationship between an older man and an adolescent, often by coercion; with only a few cases where the couple were consenting homosexual adults. About 100 of the total involved allegations of child abuse. Adolescents were generally punished more leniently than adults, but only when they were very young (under ca. 12 years) or when the case clearly concerned rape, did they have a chance to avoid punishment altogether. As a rule, the Inquisition condemned to death only those sodomites over the age of 25 years. As about half of those tried were under this age, it explains the relatively small percent of death sentences.[68]

Freemasonry

The Roman Catholic Church has regarded Freemasonry as heretical since about 1738; the suspicion of Freemasonry was potentially a capital offense. Spanish Inquisition records reveal two prosecutions in Spain and only a few more throughout the Spanish Empire.[69] In 1815, Francisco Javier de Mier y Campillo, the Inquisitor General of the Spanish Inquisition and the Bishop of Almería, suppressed Freemasonry and denounced the lodges as "societies which lead to atheism, to sedition and to all errors and crimes."[70] He then instituted a purge during which Spaniards could be arrested on the charge of being "suspected of Freemasonry".[70]

Organization

Beyond its role in religious affairs, the Inquisition was also an institution at the service of the monarchy. The Inquisitor General, in charge of the Holy Office, was designated by the crown. The Inquisitor General was the only public office whose authority stretched to all the kingdoms of Spain (including the American viceroyalties), except for a brief period (1507–1518) during which there were two Inquisitors General, one in the kingdom of Castile, and the other in Aragon.

The Inquisitor General presided over the Council of the Supreme and General Inquisition (generally abbreviated as "Council of the Suprema"), created in 1483, which was made up of six members named directly by the crown (the number of members of the Suprema varied over the course of the Inquisition's history, but it was never more than 10). Over time, the authority of the Suprema grew at the expense of the power of the Inquisitor General.

The Suprema met every morning, save for holidays, and for two hours in the afternoon on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. The morning sessions were devoted to questions of faith, while the afternoons were reserved for "minor heresies"[71] cases of perceived unacceptable sexual behavior, bigamy, witchcraft, etc.[72]

Below the Suprema were the different tribunals of the Inquisition, which were, in their origins, itinerant, installing themselves where they were necessary to combat heresy, but later being established in fixed locations. In the first phase, numerous tribunals were established, but the period after 1495 saw a marked tendency towards centralization.

In the kingdom of Castile, the following permanent tribunals of the Inquisition were established:

- 1482 In Seville and in Córdoba.

- 1485 In Toledo and in Llerena.

- 1488 In Valladolid and in Murcia.

- 1489 In Cuenca.

- 1505 In Las Palmas (Canary Islands).

- 1512 In Logroño.

- 1526 In Granada.

- 1574 In Santiago de Compostela.

There were only four tribunals in the kingdom of Aragon: Zaragoza and Valencia (1482), Barcelona (1484), and Majorca (1488).[73] Ferdinand the Catholic also established the Spanish Inquisition in Sicily (1513), housed in Palermo, and Sardinia, in the town of Sassari.[74] In the Americas, tribunals were established in Lima and in Mexico City (1569) and, in 1610, in Cartagena de Indias (present day Colombia).

Composition of the tribunals

Initially, each of the tribunals included two inquisitors, a calificador (qualifiers), an alguacil (bailiff), and a fiscal (prosecutor); new positions were added as the institution matured. The inquisitors were preferably jurists more than theologians; in 1608 Philip III even stipulated that all the inquisitors must have a background in law. The inquisitors did not typically remain in the position for a long time: for the Court of Valencia, for example, the average tenure in the position was about two years.[75] Most of the inquisitors belonged to the secular clergy (priests who were not members of religious orders) and had a university education.

The fiscal was in charge of presenting the accusation, investigating the denunciations and interrogating the witnesses by the use of physical and mental torture. The calificadores were generally theologians; it fell to them to determine if the defendant's conduct added up to a crime against the faith. Consultants were expert jurists who advised the court in questions of procedure. The court had, in addition, three secretaries: the notario de secuestros (Notary of Property), who registered the goods of the accused at the moment of his detention; the notario del secreto (Notary of the Secret), who recorded the testimony of the defendant and the witnesses; and the escribano general (General Notary), secretary of the court. The alguacil was the executive arm of the court, responsible for detaining, jailing, and physically torturing the defendant. Other civil employees were the nuncio, ordered to spread official notices of the court, and the alcaide, jailer in charge of feeding the prisoners.

In addition to the members of the court, two auxiliary figures existed that collaborated with the Holy Office: the familiares and the comissarios (commissioners). Familiares were lay collaborators of the Inquisition, who had to be permanently at the service of the Holy Office. To become a familiar was considered an honour, since it was a public recognition of limpieza de sangre — Old Christian status — and brought with it certain additional privileges. Although many nobles held the position, most of the familiares came from the ranks of commoners. The commissioners, on the other hand, were members of the religious orders who collaborated occasionally with the Holy Office.

One of the most striking aspects of the organization of the Inquisition was its form of financing: devoid of its own budget, the Inquisition depended exclusively on the confiscation of the goods of the denounced. It is not surprising, therefore, that many of those prosecuted were rich men. That the situation was open to abuse is evident, as stands out in the memorial that a converso from Toledo directed to Charles I:

"Your Majesty must provide, before all else, that the expenses of the Holy Office do not come from the properties of the condemned, because if that is the case, if they do not burn they do not eat."[76]

Accusation

When the Inquisition arrived in a city, the first step was the Edict of Grace. Following the Sunday mass, the Inquisitor would proceed to read the edict; it explained possible heresies and encouraged all the congregation to come to the tribunals of the Inquisition to "relieve their consciences". They were called Edicts of Grace because all of the self-incriminated who presented themselves within a period of grace (usually ranging from thirty to forty days) were offered the possibility of reconciliation with the Church without severe punishment.[77] The promise of benevolence was effective, and many voluntarily presented themselves to the Inquisition and were often encouraged to denounce others who had also committed offenses, informants being the Inquisition's primary source of information. After about 1500, the Edicts of Grace were replaced by the Edicts of Faith, which left out the grace period and instead encouraged the denunciation of those guilty.[78]

The denunciations were anonymous, and the defendants had no way of knowing the identities of their accusers.[79] This was one of the points most criticized by those who opposed the Inquisition (for example, the Cortes of Castile, in 1518). In practice, false denunciations were frequent. Denunciations were made for a variety of reasons, from genuine concern, to rivalries and personal jealousies.

Detention

After a denunciation, the case was examined by the calificadores, who had to determine if there was heresy involved, followed by detention of the accused. In practice, however, many were detained in preventive custody, and many cases of lengthy incarcerations occurred, lasting up to two years, before the calificadores examined the case.[80]

Detention of the accused entailed the preventive sequestration of their property by the Inquisition. The property of the prisoner was used to pay for procedural expenses and the accused's own maintenance and costs. Often the relatives of the defendant found themselves in outright misery. This situation was only remedied following instructions written in 1561.

The entire process was undertaken with the utmost secrecy, as much for the public as for the accused, who were not informed about the accusations that were levied against them. Months or even years could pass without the accused being informed about why they were imprisoned. The prisoners remained isolated, and, during this time, the prisoners were not allowed to attend Mass nor receive the sacraments. The jails of the Inquisition were no worse than those of secular authorities, and there are even certain testimonies that occasionally they were much better.[81]

Trial

The inquisitorial process consisted of a series of hearings, in which both the denouncers and the defendant gave testimony. A defense counsel was assigned to the defendant, a member of the tribunal itself, whose role was simply to advise the defendant and to encourage them to speak the truth. The prosecution was directed by the fiscal. Interrogation of the defendant was done in the presence of the Notary of the Secreto, who meticulously wrote down the words of the accused. The archives of the Inquisition, in comparison to those of other judicial systems of the era, are striking in the completeness of their documentation. In order to defend themselves, the accused had two possibilities: abonos (to find favourable witnesses, akin to "substantive" evidence/testimony in Anglo-American law) or tachas (to demonstrate that the witnesses of accusers were not trustworthy, akin to Anglo-American "impeachment" evidence/testimony).

In order to interrogate the accused, the Inquisition made use of torture, but not in a systematic way. It was applied mainly against those suspected of Judaism and Protestantism, beginning in the 16th century. For example, Lea estimates that between 1575 and 1610 the court of Toledo tortured approximately a third of those processed for heresy.[82] In other periods, the proportions varied remarkably. Torture was always a means to obtain the confession of the accused, not a punishment itself. Torture was also applied without distinction of sex or age, including children and the aged.

Torture

As with all European tribunals of the time, torture was employed.[83][84] The Spanish inquisition, however, engaged in it far less often and with greater care than other courts.[83][85] Historian Henry Kamen contends that some "popular" accounts of the inquisition (those that describe scenes of uncontrolled sadistic torture) are not based in truth. Kamen argues that torture was only ever used to elicit information or a confession, not for punitive reasons.[86] The torture lasted up to 15 minutes.[83]

Although the Inquisition was technically forbidden from permanently harming or drawing blood,[84] this still allowed several methods of torture. The methods most used, and common in other secular and ecclesiastical tribunals, were garrucha, toca and the potro.[84] The application of the garrucha, also known as the strappado, consisted of suspending the victim from the ceiling by the wrists, which are tied behind the back. Sometimes weights were tied to the ankles, with a series of lifts and drops, during which the arms and legs suffered violent pulls and were sometimes dislocated.[87] The toca, also called interrogatorio mejorado del agua, consisted of introducing a cloth into the mouth of the victim, and forcing them to ingest water spilled from a jar so that they had the impression of drowning.[88] The potro, the rack, was the instrument of torture used most frequently.[89]

The assertion that confessionem esse veram, non factam vi tormentorum (literally: '[a person's] confession is truth, not made by way of torture') sometimes follows a description of how, after torture had ended, the subject freely confessed to the offenses.[90] Thus confessions following torture were deemed to be made of the confessor's free will, and hence valid.

Once the process concluded, the inquisidores met with a representative of the bishop and with the consultores, experts in theology or Canon Law, which was called the consulta de fe. The case was voted and sentence pronounced, which had to be unanimous. In case of discrepancies, the Suprema had to be informed.

According to authorities within the Eastern Orthodox Church, there was at least one casualty tortured by those "Jesuits" (though most likely, Franciscans) who administered the Spanish Inquisition in North America: St. Peter the Aleut.

Sentencing

The results of the trial could be the following:

- Although quite rare in actual practice, the defendant could be acquitted. Inquisitors did not wish to terminate the proceedings. If they did, and new evidence turned up later, they would be forced into reopening and re-presenting the old evidence.

- The trial could be suspended, in which case the defendant, although under suspicion, went free (with the threat that the process could be continued at any time) or was held in long-term imprisonment until a trial commenced. When set free after a suspended trial it was considered a form of acquittal without specifying that the accusation had been erroneous.

- The defendant could be penanced. Since they were considered guilty, they had to publicly abjure their crimes (de levi if it was a misdemeanor, and de vehementi if the crime were serious), and accept a public punishment. Among these were sanbenito, exile, fines or even sentencing to service as oarsmen in royal galleys.

- The defendant could be reconciled. In addition to the public ceremony in which the condemned was reconciled with the Catholic Church, more severe punishments were used, among them long sentences to jail or the galleys, plus the confiscation of all property. Physical punishments, such as whipping, were also used.

- The most serious punishment was relaxation to the secular arm for burning at the stake. This penalty was frequently applied to impenitent heretics and those who had relapsed. Execution was public. If the condemned repented, they were shown mercy by being garroted before burning; if not, they were burned alive.

Frequently, cases were judged in absentia, and when the accused died before the trial finished, the condemned were burned in effigy.

The distribution of the punishments varied considerably over time. It is believed that sentences of death were enforced in the first stages within the long history of the Inquisition. According to García Cárcel, the court of Valencia employed the death penalty in 40% of the processings before 1530, but later that percentage dropped to 3%).[91]

Auto-da-fé

If the sentence was condemnatory, this implied that the condemned had to participate in the ceremony of an auto de fe (more commonly known in English as an auto-da-fé) that solemnized their return to the Church (in most cases), or punishment as an impenitent heretic. The autos-da-fé could be private (auto particular) or public (auto publico or auto general).

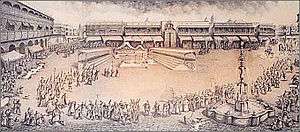

Although initially the public autos did not have any special solemnity nor sought a large attendance of spectators, with time they became solemn ceremonies, celebrated with large public crowds, amidst a festive atmosphere. The auto-da-fé eventually became a baroque spectacle, with staging meticulously calculated to cause the greatest effect among the spectators. The autos were conducted in a large public space (frequently in the largest plaza of the city), generally on holidays. The rituals related to the auto began the previous night (the "procession of the Green Cross") and sometimes lasted the whole day. The auto-da-fé frequently was taken to the canvas by painters: one of the better-known examples is the painting by Francesco Rizzi held by the Prado Museum in Madrid that represents the auto celebrated in the Plaza Mayor of Madrid on 30 June 1680. The last public auto-da-fé took place in 1691.

The auto-da-fé involved a Catholic Mass, prayer, a public procession of those found guilty, and a reading of their sentences.[92] They took place in public squares or esplanades and lasted several hours; ecclesiastical and civil authorities attended. Artistic representations of the auto-da-fé usually depict torture and the burning at the stake. However, this type of activity never took place during an auto-da-fé, which was in essence a religious act. Torture was not administered after a trial concluded, and executions were always held after and separate from the auto-da-fé,[93] though in the minds and experiences of observers and those undergoing the confession and execution, the separation of the two might be experienced as merely a technicality.

The first recorded auto-da-fé was held in Paris in 1242, during the reign of Louis IX.[94] The first Spanish auto-da-fé did not take place until 1481 in Seville; six of the men and women subjected to this first religious ritual were later executed. The Inquisition had limited power in Portugal, having been established in 1536 and officially lasting until 1821, although its influence was much weakened with the government of the Marquis of Pombal in the second half of the 18th century. Autos-da-fé also took place in Mexico, Brazil and Peru: contemporary historians of the Conquistadors such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo record them. They also took place in the Portuguese colony of Goa, India, following the establishment of Inquisition there in 1562–1563.

The arrival of the Enlightenment in Spain slowed inquisitorial activity. In the first half of the 18th century, 111 were condemned to be burned in person, and 117 in effigy, most of them for judaizing. In the reign of Philip V, there were 125 autos-da-fé, while in the reigns of Charles III and Charles IV only 44.

During the 18th century, the Inquisition changed: Enlightenment ideas were the closest threat that had to be fought. The main figures of the Spanish Enlightenment were in favour of the abolition of the Inquisition, and many were processed by the Holy Office, among them Olavide, in 1776; Iriarte, in 1779; and Jovellanos, in 1796; Jovellanos sent a report to Charles IV in which he indicated the inefficiency of the Inquisition's courts and the ignorance of those who operated them:

friars who take [the position] only to obtain gossip and exemption from choir; who are ignorant of foreign languages, who only know a little scholastic theology...[95]

In its new role, the Inquisition tried to accentuate its function of censoring publications but found that Charles III had secularized censorship procedures, and, on many occasions, the authorization of the Council of Castile hit the more intransigent position of the Inquisition. Since the Inquisition itself was an arm of the state, being within the Council of Castile, civil rather than ecclesiastical censorship usually prevailed. This loss of influence can also be explained because the foreign Enlightenment texts entered the peninsula through prominent members of the nobility or government,[96] influential people with whom it was very difficult to interfere. Thus, for example, Diderot's Encyclopedia entered Spain thanks to special licenses granted by the king.

After the French Revolution, however, the Council of Castile, fearing that revolutionary ideas would penetrate Spain's borders, decided to reactivate the Holy Office that was directly charged with the persecution of French works. An Inquisition edict of December 1789, that received the full approval of Charles IV and Floridablanca, stated that:

having news that several books have been scattered and promoted in these kingdoms... that, without being contented with the simple narration events of a seditious nature... seem to form a theoretical and practical code of independence from the legitimate powers.... destroying in this way the political and social order... the reading of thirty and nine French works is prohibited, under fine...[97]

However, inquisitorial activity was impossible in the face of the information avalanche that crossed the border; in 1792

the multitude of seditious papers... does not allow formalizing the files against those who introduce them...

The fight from within against the Inquisition was almost always clandestine. The first texts that questioned the Inquisition and praised the ideas of Voltaire or Montesquieu appeared in 1759. After the suspension of pre-publication censorship on the part of the Council of Castile in 1785, the newspaper El Censor began the publication of protests against the activities of the Holy Office by means of a rationalist critique. Valentin de Foronda published Espíritu de los Mejores Diarios, a plea in favour of freedom of expression that was avidly read in the salons. Also, in the same vein, Manuel de Aguirre wrote On Toleration in El Censor, El Correo de los Ciegos and El Diario de Madrid.[98]

End of the Inquisition

During the reign of Charles IV of Spain, in spite of the fears that the French Revolution provoked, several events took place that accelerated the decline of the Inquisition. In the first place, the state stopped being a mere social organizer and began to worry about the well-being of the public. As a result, they considered the land-holding power of the Church, in the señoríos and, more generally, in the accumulated wealth that had prevented social progress.[99] On the other hand, the perennial struggle between the power of the throne and the power of the Church, inclined more and more to the former, under which, Enlightenment thinkers found better protection for their ideas. Manuel Godoy and Antonio Alcalá Galiano were openly hostile to an institution whose only role had been reduced to censorship and was the very embodiment of the Spanish Black Legend, internationally, and was not suitable to the political interests of the moment:

The Inquisition? Its old power no longer exists: the horrible authority that this bloodthirsty court had exerted in other times was reduced... the Holy Office had come to be a species of commission for book censorship, nothing more...[100]

The Inquisition was first abolished during the domination of Napoleon and the reign of Joseph Bonaparte (1808–1812). In 1813, the liberal deputies of the Cortes of Cádiz also obtained its abolition,[101] largely as a result of the Holy Office's condemnation of the popular revolt against French invasion. But the Inquisition was reconstituted when Ferdinand VII recovered the throne on 1 July 1814. Juan Antonio Llorente, who had been the Inquisition's general secretary in 1789, became a Bonapartist and published a critical history in 1817 from his French exile, based on his privileged access to its archives.[102]

Possibly as a result of Llorente's criticisms, the Inquisition was once again temporarily abolished during the three-year Liberal interlude known as the Trienio liberal, but still the old system had not yet had its last gasp. Later, during the period known as the Ominous Decade, the Inquisition was not formally re-established,[103] although, de facto, it returned under the so-called Congregation of the Meetings of Faith, tolerated in the dioceses by King Ferdinand. On 26 July 1826 the "Meetings of Faith" Congregation condemned and executed the school teacher Cayetano Ripoll, who thus became the last person known to be executed by the Inquisition.[104]

On that day, Ripoll was hanged in Valencia, for having taught deist principles. This execution occurred against the backdrop of a European-wide scandal concerning the despotic attitudes still prevailing in Spain. Finally, on 15 July 1834, the Spanish Inquisition was definitively abolished by a Royal Decree signed by regent Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies, Ferdinand VII's liberal widow, during the minority of Isabella II and with the approval of the President of the Cabinet Francisco Martínez de la Rosa. (It is possible that something similar to the Inquisition acted during the 1833–1839 First Carlist War, in the zones dominated by the Carlists, since one of the government measures praised by Conde de Molina Carlos Maria Isidro de Borbon was the re-implementation of the Inquisition to protect the Church). During the Carlist Wars it was the conservatives who fought the liberals who wanted to reduce the Church's power, amongst other reforms to liberalize the economy. It can be added that Franco during the Spanish Civil War is alleged to have stated that he would attempt to reintroduce it, possibly as a sop to Vatican approval of his coup.

The Alhambra Decree that had expelled the Jews was formally rescinded on 16 December 1968.[105]

Outcomes

Confiscations

It is unknown exactly how much wealth was confiscated from converted Jews and others tried by the Inquisition. Wealth confiscated in one year of persecution in the small town of Guadaloupe paid the costs of building a royal residence.[106] There are numerous records of the opinion of ordinary Spaniards of the time that "the Inquisition was devised simply to rob people". "They were burnt only for the money they had", a resident of Cuenca averred. "They burn only the well-off", said another. In 1504 an accused stated, "only the rich were burnt". …In 1484…Catalina de Zamora was accused of asserting that "this Inquisition that the fathers are carrying out is as much for taking property from the conversos as for defending the faith. It is the goods that are the heretics." This saying passed into common usage in Spain. In 1524 a treasurer informed Charles V that his predecessor had received ten million ducats from the conversos, but the figure is unverified. In 1592 an inquisitor admitted that most of the fifty women he arrested were rich. In 1676, the Suprema claimed it had confiscated over 700,000 ducats for the royal treasury (which was paid money only after the Inquisition's own budget, amounting in one known case to only 5%). The property on Mallorca alone in 1678 was worth "well over 2,500,000 ducats".[107]

Death tolls

García Cárcel estimates that the total number processed by the Inquisition throughout its history was approximately 150,000; applying the percentages of executions that appeared in the trials of 1560–1700—about 2%—the approximate total would be about 3,000 put to death. Nevertheless, it is likely that the toll was higher, keeping in mind the data provided by Dedieu and García Cárcel for the tribunals of Toledo and Valencia, respectively. It is likely that between 3,000 and 5,000 were executed.[108]

Modern historians have begun to study the documentary records of the Inquisition. The archives of the Suprema, today held by the National Historical Archive of Spain (Archivo Histórico Nacional), conserves the annual relations of all processes between 1540 and 1700. This material provides information on about 44,674 judgements, the latter studied by Gustav Henningsen and Jaime Contreras. These 44,674 cases include 826 executions in persona and 778 in effigie. This material, however, is far from being complete—for example, the tribunal of Cuenca is entirely omitted, because no relaciones de causas from this tribunal have been found, and significant gaps concern some other tribunals (e.g., Valladolid). Many more cases not reported to the Suprema are known from the other sources (i.e., no relaciones de causas from Cuenca have been found, but its original records have been preserved), but were not included in Contreras-Henningsen's statistics for the methodological reasons.[109] William Monter estimates 1000 executions between 1530 and 1630 and 250 between 1630 and 1730.[110]

The archives of the Suprema only provide information surrounding the processes prior to 1560. To study the processes themselves, it is necessary to examine the archives of the local tribunals; however, the majority have been lost to the devastation of war, the ravages of time or other events. Jean-Pierre Dedieu has studied those of Toledo, where 12,000 were judged for offences related to heresy.[111] Ricardo García Cárcel has analyzed those of the tribunal of Valencia.[112] These authors' investigations find that the Inquisition was most active in the period between 1480 and 1530, and that during this period the percentage condemned to death was much more significant than in the years studied by Henningsen and Contreras. Henry Kamen gives the number of about 2,000 executions in persona in the whole of Spain up to 1530.[113]

Henningsen-Contreras statistics for the period 1540–1700

The statistics of Henningsen and Contreras, based entirely on relaciones de causas, are following:

| Tribunal | Number of years with preserved relaciones de causas from the period 1540–1700[114] | Number of cases reported in the preserved relaciones de causas[115] | Executions in persona reported in the preserved relaciones de causas[115] | Executions in effigie reported in the preserved relaciones de causas[115] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 94 | 3047 | 37 | 27 |

| Navarre | 130 | 4296 | 85 | 59 |

| Majorca | 96 | 1260 | 37 | 25 |

| Sardinia | 49 | 767 | 8 | 2 |

| Zaragoza | 126 | 5967 | 200 | 19 |

| Sicily | 101 | 3188 | 25 | 25 |

| Valencia | 128 | 4540 | 78 | 75 |

| Cartagena (established 1610) | 62 | 699 | 3 | 1 |

| Lima (established 1570) | 92 | 1176 | 30 | 16 |

| Mexico (established 1570) | 52 | 950 | 17 | 42 |

| Aragonese Secretariat (total) | 930 | 25890 | 520 | 291 |

| Canaries | 66 | 695 | 1 | 78 |

| Córdoba | 28 | 883 | 8 | 26 |

| Cuenca | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Galicia (established 1560) | 83 | 2203 | 19 | 44 |

| Granada | 79 | 4157 | 33 | 102 |

| Llerena | 84 | 2851 | 47 | 89 |

| Murcia | 66 | 1735 | 56 | 20 |

| Seville | 58 | 1962 | 96 | 67 |

| Toledo (incl. Madrid) | 108 | 3740 | 40 | 53 |

| Valladolid | 29 | 558 | 6 | 8 |

| Castilian Secretariat (total) | 601 | 18784 | 306 | 487 |

| Total | 1531 | 44674 | 826 | 778 |

The actual numbers, as far as they can be reconstructed from the available sources, are following:

| Tribunal | Estimated number of all trials in the period 1540–1700[116] | The number of executions in persona in the period 1540–1700[117] |

|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | ~5000 | 53[118] |

| Navarre | ~5200 | 90[118] |

| Majorca | ~2100 | 38[119] |

| Sardinia | ~2700 | At least 8 |

| Zaragoza | ~7600 | 250[118] |

| Sicily | ~6400 | 52[118] |

| Valencia | ~5700 | At least 93[118] |

| Cartagena (established 1610) | ~1100 | At least 3 |

| Lima (established 1570) | ~2200 | 31[120] |

| Mexico (established 1570) | ~2400 | 47[121] |

| Aragonese Secretariat (total) | ~40000 | At least 665 |

| Canaries | ~1500 | 3[122] |

| Córdoba | ~5000 | At least 27[123] |

| Cuenca | 5202[124] | At least 34[125] |

| Galicia (established 1560) | ~2700 | 17[126] |

| Granada | ~8100 | At least 72[127] |

| Llerena | ~5200 | At least 47 |

| Murcia | ~4300 | At least 190[128] |

| Seville | ~6700 | At least 128[129] |

| Toledo (incl. Madrid) | ~5500 | At least 66[130] |

| Valladolid | ~3000 | At least 54[131] |

| Castilian Secretariat (total) | ~47000 | At least 638 |

| Total | ~87000 | At least 1303 |

Autos da fe between 1701 and 1746

Table of sentences pronounced in the public autos da fe in Spain (excluding tribunals in Sicily, Sardinia and Latin America) between 1701 and 1746:[132]

| Tribunal | Number of autos da fe | Executions in persona | Executions in effigie | Penanced | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 8 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 17 |

| Logroño | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0? | 1? |

| Palma de Mallorca | 3 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Saragossa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Valencia | 4 | 2 | 0 | 49 | 51 |

| Las Palmas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Córdoba | 13 | 17 | 19 | 125 | 161 |

| Cuenca | 7 | 7 | 10 | 35 | 52 |

| Santiago de Compostela | 4 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 13 |

| Granada | 15 | 36 | 47 | 369 | 452 |

| Llerena | 5 | 1 | 0 | 45 | 46 |

| Madrid | 4 | 11 | 13 | 46 | 70 |

| Murcia | 6 | 4 | 1 | 106 | 111 |

| Seville | 15 | 16 | 10 | 220 | 246 |

| Toledo | 33 | 6 | 14 | 128 | 148 |

| Valladolid | 10 | 9 | 2 | 70 | 81 |

| Total | 125 | 111 | 117 | 1235 | 1463 |

Abuse of power

Author Toby Green notes that the great unchecked power given to inquisitors meant that they were "widely seen as above the law"[133] and sometimes had motives for imprisoning and sometimes executing alleged offenders other than the punishment of religious nonconformity. Among the "litany of complaints" against Juan de Mañozca—who was one of the first inquisitors of Cartagena, Colombia in 1609 and made chief inquisitor of Mexico in 1643—was that he "made a habit of hauling market traders before [him and a colleague] and seizing whatever took their fancy, throwing them into the inquisitorial jail if they did not comply."[133][134] When a butcher in a house next door to Mañozca's disturbed him by killing a pig, Mañozca had the butcher's butler and servants arrested and interned in the inquisitorial jail.[133][135]

Green quotes a complaint by historian Manuel Barrios[136] about one Inquisitor, Diego Rodriguez Lucero, who in Cordoba in 1506 burned to death the husbands of two different women he then kept as mistresses. According to Barrios,

the daughter of Diego Celemin was exceptionally beautiful, her parents and her husband did not want to give her to [Lucero], and so Lucero had the three of them burnt and now has a child by her, and he has kept for a long time in the alcazar as a mistress.[137]

Historiography

How historians and commentators have viewed the Spanish Inquisition has changed over time, and continues to be a source of controversy to this day. Before and during the 19th century historical interest focused on who was being persecuted. In the early and mid 20th century historians examined the specifics of what happened and how it influenced Spanish history. In the later 20th and 21st century, historians have re-examined how severe the Inquisition really was, calling into question some of the conclusions made earlier in the 20th century. The "Black Legend", a term associated with scholar Julian Juderias, developed significantly, in his view, from the approach of considering the Inquisition's persecutions.[138]

19th to early 20th century scholarship

Before the rise of professional historians in the 19th century, the Spanish Inquisition had largely been studied and portrayed by Protestant scholars who saw it as the archetypal symbol of Catholic intolerance and ecclesiastical power.[139] The Spanish Inquisition for them was largely associated with the persecution of Protestants.[139] The 19th-century professional historians, including the Spanish scholar Amador de los Rios, were the first to challenge this perception and look seriously at the role of Jews and Muslims.[139]

At the start of the 20th century Henry Charles Lea published the groundbreaking History of the Inquisition in Spain. This influential work saw the Spanish Inquisition as "an engine of immense power, constantly applied for the furtherance of obscurantism, the repression of thought, the exclusion of foreign ideas and the obstruction of progress."[139] Lea documented the Inquisition's methods and modes of operation in no uncertain terms, calling it "theocratic absolutism" at its worst.[139] In the context of the polarization between Protestants and Catholics during the second half of the 19th century,[140] some of Lea's contemporaries, as well as most modern scholars thought Lea's work had an anti-Catholic bias.[140][141] William H. Prescott, the Boston historian, likened the Inquisition to an "eye that never slumbered".

Starting in the 1920s, Jewish scholars picked up where Lea's work left off.[139] They published Yitzhak Baer's History of the Jews in Christian Spain, Cecil Roth's History of the Marranos and, after World War II, the work of Haim Beinart, who for the first time published trial transcripts of cases involving conversos.

Revision after 1960

One of the first books to challenge the classical view was The Spanish Inquisition (1965) by Henry Kamen. Kamen argued that the Inquisition was not nearly as cruel or as powerful as commonly believed. The book was very influential and largely responsible for subsequent studies in the 1970s to try to quantify (from archival records) the Inquisition's activities from 1480 to 1834.[142] Those studies showed there was an initial burst of activity against conversos suspected of relapsing into Judaism, and a mid-16th century pursuit of Protestants, but the Inquisition served principally as a forum Spaniards occasionally used to humiliate and punish people they did not like: blasphemers, bigamists, foreigners and, in Aragon, homosexuals and horse smugglers.[139] Kamen went on to publish two more books in 1985 and 2006 that incorporated new findings, further supporting the view that the Inquisition was not as bad as once described by Lea and others. Along similar lines is Edward Peters's Inquisition (1988).

One of the most important works in challenging traditional views of the Inquisition as it related to the Jewish conversos or New Christians, is The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth Century Spain (1995/2002) by Benzion Netanyahu. It challenges the view that most conversos were actually practicing Judaism in secret and were persecuted for their crypto-Judaism. Rather, according to Netanyahu, the persecution was fundamentally racial, and was a matter of envy of their success in Spanish society.[143]

Challenging some of the claims of revisionist historians is Toby Green in Inquisition, the Reign of Fear, who calls the claim by revisionists that torture was only rarely applied by inquisitors, a "worrying error of fact".[144]

Historian Thomas Madden has written about popular myths of the Inquisition.[145]

In popular culture

Literature

The literature of the 18th century approaches the theme of the Inquisition from a critical point of view. In Candide by Voltaire, the Inquisition appears as the epitome of intolerance and arbitrary justice in Europe.

During the Romantic Period, the Gothic novel, which was primarily a genre developed in Protestant countries, frequently associated Catholicism with terror and repression. This vision of the Spanish Inquisition appears in, among other works, The Monk (1796) by Matthew Gregory Lewis (set in Madrid during the Inquisition, but can be seen as commenting on the French Revolution and the Terror); in Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) by Charles Robert Maturin and in The Manuscript Found in Saragossa by Polish author Jan Potocki.

19th-century literature tends to focus on the element of torture employed by the Inquisition. In France, in the early 19th century, the epistolary novel Cornelia Bororquia, or the Victim of the Inquisition, which has been attributed to Spaniard Luiz Gutiérrez, and is based on the case of María de Bohórquez, ferociously criticizes the Inquisition and its representatives. The Inquisition also appears in one of the chapters of the novel The Brothers Karamazov (1880) by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, which imagines an encounter between Jesus and the Inquisitor General. One of the best known stories of Edgar Allan Poe, "The Pit and the Pendulum", explores along the same lines the use of torture by the Inquisition.

The Inquisition also appears in 20th-century literature. La Gesta del Marrano, by the Argentine author Marcos Aguinis, portrays the length of the Inquisition's arm to reach people in Argentina during the 16th and 17th centuries. The Marvel Comics series Marvel 1602 shows the Inquisition targeting Mutants for "blasphemy". The character Magneto also appears as the Grand Inquisitor. The Captain Alatriste novels by the Spanish writer Arturo Pérez-Reverte are set in the early 17th century. The second novel, Purity of Blood, has the narrator being tortured by the Inquisition and describes an auto-da-fé. Carme Riera's novella, published in 1994, Dins el Darrer Blau (In the Last Blue) is set during the repression of the chuetas (conversos from Majorca) at the end of the 17th century. In 1998, the Spanish writer Miguel Delibes published the historical novel The Heretic, about the Protestants of Valladolid and their repression by the Inquisition. Samuel Shellabarger's Captain from Castile deals directly with the Spanish Inquisition during the first part of the novel.

Film

- The 1947 epic Captain from Castile by Darryl F. Zanuck, starring Tyrone Power, uses The Inquisition as the major plot point of the film. It tells how powerful families used its evils to ruin their rivals. The first part of the film shows this and the reach of the Inquisition reoccurs throughout this movie following Pedro De Vargas (played by Power) even to the 'New World'.

- In both the stage (1965) and film (1972) versions of the musical play Man of La Mancha, Miguel de Cervantes is arrested by the Spanish Inquisition and thrown into a dungeon, in which he and the other prisoners perform the story of Don Quixote. At the end of the musical, he and his manservant are escorted by the Inquisition to their trial.

- The Spanish Inquisition segment of the 1981 Mel Brooks movie The History of the World Part 1 is a comedic musical performance based on the activities of the first Inquisitor General of Spain, Tomás de Torquemada.

- The film The Fountain (2006) by Darren Aronofsky, features the Spanish Inquisition as part of a plot in 1500 when the Grand Inquisitor threatens Queen Isabella's life.

- Goya's Ghosts (2006) by Miloš Forman is set in Spain between 1792 and 1809 and focuses realistically on the role of the Inquisition and its end under Napoleon's rule.

- The upcoming film Assassin's Creed (2016) by Justin Kurzel, starring Michael Fassbender, is set in both modern times and Spain during the Inquisition. The film follows Callum Lynch (played by Fassbender) as he is forced to relive the memories of his ancestor, Aguilar de Nehra (also played by Fassbender), an Assassin during the Spanish Inquisition.

Theatre, music, television, and video games

- The Grand Inquisitor of Spain plays a part in Don Carlos, (1867) a play by Friedrich Schiller (which was the basis for the opera in five acts by Giuseppe Verdi, in which the Inquisitor is also featured, and the third act is dedicated to an auto-da-fé).

- In the Monty Python comedy team's Spanish Inquisition sketches, an inept Inquisitor group repeatedly bursts into scenes after someone utters the words "I didn't expect the Spanish Inquisition", screaming "Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!" The Inquisition then uses ineffectual forms of torture, including a dish-drying rack, soft cushions and a comfy chair.

- The Spanish Inquisition features as a main plot line element of the 2009 video game Assassin's Creed II: Discovery.

See also

- Black Legend of the Spanish Inquisition

- Cardinal Ximenes

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

- Death by burning

- Goa Inquisition in Portuguese Goa

- List of Grand Inquisitors of Spain

- Historical revision of the Inquisition

- History of the Jews in Spain

- Holy Child of La Guardia

- Inquisition

- Medieval Inquisition

- Mexican Inquisition in New Spain

- Inquisition of the Netherlands in the Spanish Netherlands

- Persecution of Christians

- Persecution of Muslims

- Peruvian Inquisition in the Viceroyalty of Peru

- Portuguese Inquisition

- Roman Inquisition

- The Spanish Inquisition (Monty Python)

References

Notes

- 1 2 Hans-Jürgen Prien (21 November 2012). Christianity in Latin America: Revised and Expanded Edition. BRILL. p. 11. ISBN 90-04-22262-6.

- ↑ Henry Kamen: The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. 1999

- ↑ Smith, Damian J., Crusade, Heresy and Inquisition in the Lands of the Crown of Aragon, Brill, 2010 ISBN 9789004182899

- ↑ Kamen (1998), p. 4

- ↑ Peters 1988, p. 79.

- ↑ Peters 1988, p. 82.

- 1 2 Letter of Hasdai Crescas, Shevaṭ Yehudah by Solomon ibn Verga (ed. Dr. M. Wiener), Hannover 1855, pp. 128 – 130, or pp. 138 - 140 in PDF; Fritz Kobler, Letters of the Jews through the Ages, London 1952, pp. 272–75; Mitre Fernández, Emilio (1994). Secretariado de Publicaciones e Intercambio Editorial, ed. Los judíos de Castilla en tiempo de Enrique III : el pogrom de 1391 [The Castilian Jews at the time of Henry III: the 1391 pogrom] (in Spanish). Valladolid University. ISBN 84-7762-449-6.; Solomon ibn Verga, Shevaṭ Yehudah (The Sceptre of Judah), Lvov 1846, p. 76 in PDF.

- ↑ Letter from Hasdai Crescas to the congregations of Avignon, published as an appendix to Wiener's edition of Shevaṭ Yehudah of Solomon ibn Verga, in which he names the Jewish communities affected by the persecution of 1391. See pages 138 – 140 in PDF (Hebrew); Fritz Kobler, Letters of the Jews through the Ages, London 1952, pp. 272–75.

- ↑ Solomon ibn Verga, Shevaṭ Yehudah (The Sceptre of Judah), Lvov 1846, pp. 41 (end) – 42 in PDF); Kamen (1998), p. 17. Kamen cites approximate numbers for Valencia (250) and Barcelona (400), but no solid data about Córdoba.

- ↑ According to Gedaliah Ibn Yechia, these disturbances were caused by a malicious report spread about the Jews. See: Gedaliah Ibn Yechia, Shalshelet Ha-Kabbalah Jerusalem 1962, p. רסח, in PDF p. 277 (top) (Hebrew); Solomon ibn Verga, Shevat Yehudah, Lvov 1846 (p. 76 in PDF) (Hebrew).