Caucasian War

| The Caucasian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

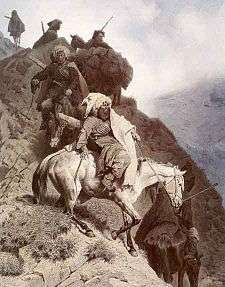

Franz Roubaud's A Scene from the Caucasian War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Big Kabarda (to 1825) Dagestan free people | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Tsar Nicholas I Tsar Alexander I Tsar Alexander II Aleksey Yermolov Mikhail Vorontsov Aleksandr Baryatinskiy Ivan Paskevich Nikolai Yevdokimov |

Imam Shamil Gamzat-bek Ghazi Mullah Kazbech Tuguzhoko Akhmat Aublaa Shabat Marshan Haji Kerantukh Berzek | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| about 250,000 | unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| roughly 96,000 | unknown | ||||||||

The Caucasian War (Russian: Кавказская война; Kavkazskaya voyna) of 1817–1864 was an invasion of the Caucasus by the Russian Empire which resulted in Russia's annexation of the areas of the North Caucasus, and the Ethnic cleansing of Circassians. It consisted of a series of military actions waged by Russia against territories and tribal groups in Caucasia including: Chechnya, Dagestan, the Circassians (Adyghe, Kabarday), Abkhaz, Abazins, and Ubykh, as Russia sought to expand southward.[1] In Dagestan, resistance to the Russians has been described as jihad.[2]

Russian control of the Georgian Military Highway in the center divided the Caucasian War into the Russo-Circassian War in the west and the Murid War in the east.

Other territories of the Caucasus (comprising contemporary Georgia, southern Dagestan, Armenia and Azerbaijan) were incorporated into the Russian empire at various times in the 19th century as a result of Russian wars with Persia.[3]

History

The war took place during the administrations of three successive Russian Tsars: Alexander I (reigned 1801–1825), Nicholas I (1825–1855), and Alexander II (1855–1881). The leading Russian commanders included Aleksey Petrovich Yermolov in 1816–1827, Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov in 1844–1853, and Aleksandr Baryatinskiy in 1853–1856. The writers Mikhail Lermontov and Leo Tolstoy, who gained much of his knowledge and experience of war for his book War and Peace from these encounters, took part in the hostilities. The Russian poet Alexander Pushkin referred to the war in his Byronic poem The Prisoner of the Caucasus (Kavkazskiy plennik (Кавказский пленник), 1821). In general, the Russian armies that served in the Caucasian wars were very eclectic; as well as ethnic Russians from various parts of the Russian empire they included Cossacks, Armenians, Georgians, Caucasus Greeks, Ossetians, and even soldiers of Muslim background like Tatars and Turkmen.

The Russian invasion encountered fierce resistance. The first period of the invasion ended coincidentally with the death of Alexander I and the Decembrist Revolt in 1825. It achieved surprisingly little success, especially compared with the then recent Russian victory over the "Great Army" of Napoleon in 1812.

Between 1825 and 1833, little military activity took place in the Caucasus against the native North Caucasians as wars with Turkey (1828/1829) and with Persia (1826–1828) occupied the Russians. After considerable successes in both wars, Russia resumed fighting in the Caucasus against the various rebelling native ethnic groups in the North Caucasus. Russian units again met resistance, notably led by Ghazi Mollah, Gamzat-bek, and Hadji Murad. Imam Shamil followed them. He led the mountaineers from 1834 until his capture by Dmitry Milyutin in 1859. In 1843, Shamil launched a sweeping offensive aimed at the Russian outposts in Avaria. On 28 August 1843, 10,000 men converged, from three different directions, on a Russian column in Untsukul, killing 486 men. In the next four weeks, Shamil captured every Russian outpost in Avaria except one, exacting over 2,000 casualties on the Russian defenders. He feigned an invasion north to capture a key chokepoint at the convergence of the Avar and Kazi-Kumukh rivers.[4] In 1845, Shamil's forces achieved their most dramatic success when they withstood a major Russian offensive led by Prince Vorontsov.

During the Crimean War of 1853–1856, the Russians brokered a truce with Shamil, but hostilities resumed in 1855. Warfare in the Caucasus finally ended between 1856 and 1859, when a 250,000 strong army under General Baryatinsky broke the mountaineers' resistance.

The war in the Eastern part of the North Caucasus ended in 1859; the Russians captured Shamil, forced him to surrender, to swear allegiance to the Tsar, and then exiled him to Central Russia. However, the war in the Western part of the North Caucasus resumed with the Circassians (Adyghe, Abkhazian, and Ubykh) resuming the fight. A manifesto of Tsar Alexander II declared hostilities at an end on June 2, 1864 (May 21 OS), 1864.

Among post-war events, a tragic page in the history of the indigenous peoples of the Caucasus (especially the Circassians), was Muhajirism, or population transfer of the Muslim population to the Ottoman Empire, and to a lesser extent Persia.[5]

Aftermath

Many Circassians fled to the Ottoman Empire and, to a lesser extent, Persia. Circassians became the first target of Arab Armies during the first Arab-Israeli war. They helped to mobilize Jewish settlers during the siege of Circassian villages in Palestine by Arab armies, and to create an Israeli army. Circassians from Kosovo returned to Russia only after the civil war in Kosovo. There are many Circassians in Syria now who are preparing to repatriate. Some Circassians joined Cossacks. Grebensky (Row) Cossacks were of mixed Russian-Circassian origin from the very beginning. There were Mozdok Cossacks of Circassian origin as well. The genocide of Terek Cossacks during the Civil war was a continuation of the genocide of Circassians, former allies of the Russian Empire who supported the Communists. Adyghea, Oset, Kabardino-Balkarian, and Karachaevo-Circassian republics have some sovereign rights within Russia. The problems of Circassian republics within Russia originate from the distribution of many Circassian tribal lands among the allies of the Russian Empire in the Caucasus, especially Vainahs and Turkic peoples. Many new settlers were exiled by Stalin in 1944, and some of their land was given to Georgians and Ossetians. Though numerous exiled people have returned, many lands, granted to them by the Russian empire, are still inhabited by the Ossetians, supported by Cossacks and Russians. The Georgians all left the lands given to them. They did not consider it theirs since the land was not within Georgia itself, but lands in a neighboring country. This still generates tensions (East Prigorodny Conflict) in the former war theaters of the Caucasian war.[6]

Gallery

-

Karte des Kaukasischen Isthmus. Entworfen und gezeichnet von J. Grassl, 1856.

-

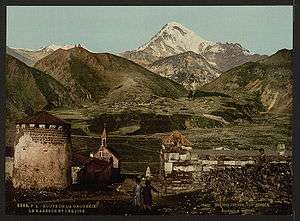

Construction of the Georgian Military Road through disputed territories was a key factor in the eventual Russian success

-

Assault of Gimry, by Franz Alekseyevich Roubaud

-

Caucasian tribesmen fight against the Cossacks, 1847

-

Storm of the fortress of Akhty in 1848

-

Circassians by Theodor Horschelt

-

Imam Shamil surrendered to Count Baryatinsky on August 25, 1859

-

Mountaineers leave the aul, by Pyotr Gruzinsky

-

Russian medal for subjugation of Western Caucasus 1859–1864

References

- ↑ Charles King The ghost of freedom: a history of the Caucasus Oxford University Press US, 2008 ISBN 0-19-517775-4 ISBN 978-0-19-517775-6

- ↑ Michael Kemper (2010). "An Islamd of Classical Arabic in the Caucasus: Dagestan". In Companjen, Françoise. Exploring the Caucasus in the 21st Century: Essays on Culture, History and ... Amsterdam University Press.

- ↑ "Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond ...". Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ Robert F Baumann and Combat Studies Institute (U.S.), Russian-Soviet Unconventional Wars in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Afghanistan (Fort Leavenworth, Kan: Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, n.d.)

- ↑ Yale University paper Archived December 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bertolt Brecht The Caucasian Chalk Circle study guide http://www.gradesaver.com/the-caucasian-chalk-circle/study-guide/

Further reading

- Journal of a residence in Circassia during the years 1837, 1838, and 1839 - Bell, James Stanislaus (English)

- Dubrovin, N. Russian: (Дубровин Н.Ф.) История войны и владычества русских на Кавказе, volumes 4–6. SPb, 1886–88.

- Kaziev, Shapi. Imam Shamil. "Molodaya Gvardiya" publishers. Moscow, 2001, 2003, 2006, 2010

- Kaziev, Shapi. Akhoulgo. Caucasian War of 19th century. The historical novel. "Epoch", Publishing house. Makhachkala, 2008. ISBN 978-5-98390-047-9