Soviet occupation of the Baltic states (1940)

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| Occupation of the Baltic states |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Estonia

Latvia Lithuania |

The Soviet occupation of the Baltic states covers the period from the Soviet–Baltic mutual assistance pacts in 1939, to their invasion and annexation in 1940, to the mass deportations of 1941.

In September and October 1939 the Soviet government compelled the much smaller Baltic states to conclude mutual assistance pacts which gave the Soviets the right to establish military bases there. Following invasion by the Red Army in the summer of 1940, Soviet authorities compelled the Baltic governments to resign. The presidents of Estonia and Latvia were imprisoned and later died in Siberia. Under Soviet supervision, new puppet communist governments and fellow travelers arranged rigged elections with falsified results. Shortly thereafter, the newly elected "people's assemblies" passed resolutions requesting admission into the Soviet Union. In June 1941 the new Soviet governments carried out mass deportations of "enemies of the people". Consequently, at first many Balts greeted the Germans as liberators when they occupied the area a week later.[1]

Background

After the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939, in accordance with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact the Soviet forces were given freedom over Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, an important aspect of the agreement to the Soviet government as they were afraid of Germany using the three states as a corridor to get close to Leningrad.[2]:31 the Soviets pressured Finland and the Baltic states to conclude mutual assistance treaties. The Soviets questioned the neutrality of Estonia following the escape of a Polish submarine from Tallinn on 18 September. A week after on 24 September, the Estonian foreign minister was given an ultimatum in Moscow. The Soviets demanded the conclusion of a treaty of mutual assistance to establish military bases in Estonia.[3][4] The Estonians had no choice but to allow the establishment of Soviet naval, air and army bases on two Estonian islands and at the port of Paldiski.[3] The corresponding agreement was signed on 28 September 1939. Latvia followed on 5 October 1939 and Lithuania shortly thereafter, on 10 October 1939. The agreements permitted the Soviet Union to establish military bases on the Baltic states' territory for the duration of the European war[4] and station 25,000 Soviet soldiers in Estonia, 30,000 in Latvia and 20,000 in Lithuania from October 1939.

In 1939 Finland had rejected similar Soviet demands for Finland ceding or leasing parts of its territory. Consequently, the Soviet Union attacked Finland, starting the Winter War in November. The war ended in March 1940 with Finnish territorial losses exceeding the pre-war Soviet demands, but Finland kept its sovereignty. The Baltic states were neutral in the Winter War and the Soviets praised their relations with the USSR as exemplary.[5]

Soviet occupation

Soviet military plans

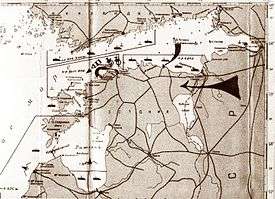

The Soviet troops allocated for possible military actions against the Baltic states numbered 435,000 troops, around 8,000 guns and mortars, over 3,000 tanks, and over 500 armoured cars.[6] On 3 June 1940 all Soviet military forces based in Baltic states were concentrated under the command of Aleksandr Loktionov.[7] On 9 June the directive 02622ss/ov was given to the Red Army's Leningrad Military District by Semyon Timoshenko to be ready by 12 June to a) capture the vessels of the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian navies in their bases or at sea; b) capture the Estonian and Latvian commercial fleets and all other vessels; c) prepare for an invasion and landing in Tallinn and Paldiski; d) close the Gulf of Riga and blockade the coasts of Estonia and Latvia in the Gulf of Finland and Baltic Sea; e) prevent an evacuation of the Estonian and Latvian governments, military forces and assets; f) provide naval support for an invasion towards Rakvere; and g) prevent Estonian and Latvian airplanes from flying either to Finland or Sweden.[8]

On 12 June 1940, according to the director of the Russian State Archive of the Naval Department Pavel Petrov (C.Phil.) referring to the records in the archive,[9][10] the Soviet Baltic Fleet was ordered to implement a total military blockade of Estonia. On 13 June at 10:40 AM Soviet forces started to move to their positions and were ready by 14 June at 10 PM: Four submarines and a number of light navy units were positioned in the Baltic Sea, in the Gulfs of Riga and Finland to isolate the Baltic states by the sea; a navy squadron including three destroyer divisions was positioned to the west of Naissaar in order to support the invasion; the 1st marine brigade's four battalions were positioned on the transport ships Sibir, 2nd Pjatiletka and Elton for landings on the islands Naissaare and Aegna; the transport ship Dnester and destroyers Storozevoi and Silnoi were positioned with troops for the invasion of the capital Tallinn; the 50th battalion was positioned on ships for an invasion near Kunda. 120 Soviet vessels participated in the naval blockade, including one cruiser, seven destroyers, and seventeen submarines, along with 219 airplanes including the 8th air-brigade with 84 DB-3 and Tupolev SB bombers and the 10th brigade with 62 airplanes.[11]

On 14 June 1940 the Soviets issued an ultimatum to Lithuania. The Soviet military blockade of Estonia went into effect while the world's attention was focused on the fall of Paris to Nazi Germany. Two Soviet bombers downed the Finnish passenger airplane "Kaleva" flying from Tallinn to Helsinki carrying three diplomatic pouches from the U.S. legations in Tallinn, Riga and Helsinki. The US Foreign Service employee Henry W. Antheil, Jr. was killed in the crash.[12]

Red Army invades

Molotov had accused the Baltic states of conspiracy against the Soviet Union and delivered an ultimatum to all Baltic countries for the establishment of Soviet-approved governments. Threatening invasion and accusing the three states of violating the original pacts as well as forming a conspiracy against the Soviet Union, Moscow presented ultimatums, demanding new concessions, which included the replacement of their governments and allowing an unlimited number of troops to enter the three countries.[13][14][15][16]

The Baltic governments had decided that, given their international isolation and the overwhelming Soviet forces on their borders and already on their territories, it was futile to actively resist and better to avoid bloodshed in an unwinnable war.[17] The occupation of the Baltic states coincided with a communist coup d'état in each country, supported by the Soviet troops.[18]

On 15 June the USSR invaded Lithuania[19] and Soviet troops attacked the Latvia border guards at Masļenki.[20] On 16 June 1940 the USSR invaded Estonia and Latvia.[19] According to a Time magazine article published at the time of the invasions, in a matter of days around 500,000 Soviet Red Army troops occupied the three Baltic states—just one week before the Fall of France to Nazi Germany.[21]

Hundreds of thousands Soviet troops entered Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania.[22] These additional Soviet military forces far outnumbered the armies of each country.[23]

Most of the Estonian Defence Forces and the Estonian Defence League surrendered according to the orders of the Estonian Government and were disarmed by the Red Army.[24][25] Only the Estonian Independent Signal Battalion stationed in Tallinn at Raua Street showed resistance to the Red Army and "People's Self-Defence" Communist militia,[26] fighting the invading troops on 21 June 1940.[27] As the Red Army brought in additional reinforcements supported by six armoured fighting vehicles, the battle lasted several hours until sundown. Finally the military resistance was ended with negotiations and the Independent Signal Battalion surrendered and was disarmed.[28] There were two dead Estonian servicemen, Aleksei Männikus and Johannes Mandre, and several wounded on the Estonian side and about ten killed and more wounded on the Soviet side.[29][30] The Soviet militia that participated in the battle was led by Nikolai Stepulov.[31]

Western Reaction

Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty at the time, said in his 1939 radio broadcast:[32][33] That the Russian armies should stand on this line was clearly necessary for the safety of Russia against the Nazi menace. At any rate, the line is there, and an Eastern front has been created which Nazi Germany does not dare assail. When Herr von Ribbentrop was summoned to Moscow last week it was to learn the fact, and to accept the fact, that the Nazi designs upon the Baltic States and upon the Ukraine must come to a dead stop.

Governments in exile - with legations in London - were recognised by a number of Western governments throughout the Cold War. With the reestablishment of independence by the Soviet Republics leaving the USSR, these governments in exile were integrated into the new governing establishments.

Sovietization of the Baltic states

Political repressions followed with mass deportations of around 130,000 citizens carried out by the Soviets.[2]:48 The Serov Instructions, "On the Procedure for carrying out the Deportation of Anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia", contained detailed procedures and protocols to observe in the deportation of Baltic nationals.

The Soviets began a constitutional metamorphosis of the Baltic states by first forming transitional "People's Governments."[34] Led by Stalin’s close associates,[35] and local communist supporters as well as officials brought in from the Soviet Union, they forced the presidents and governments of all three countries to resign, replacing them with the provisional People's Governments.

On 14–15 July, following illegal amendments to the electoral laws of the respective states, rigged parliamentary elections for the "People's Parliaments"[36] were conducted by local Communists loyal to the Soviet Union. The laws were worded in such a way that the Communists and their allies were the only ones allowed to run.[36][37] The election results were completely fabricated: the Soviet press service released them early, with the results having already appeared in print in a London newspaper a full 24 hours before the polls closed.[38][39] The "People's Parliaments" met on 21 July, each with only one piece of business—a request to join the Soviet Union. These requests carried unanimously. In early August, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR "accepted" all three requests. The official Soviet line was that all three Baltic states carried out socialist revolutions and voluntarily requested to join the Soviet Union.

The new Soviet-installed governments in the Baltic states began to align their policies with current Soviet practices.[40] According to the prevailing doctrine in the process, the old "bourgeois" societies were destroyed so that new socialist societies, run by loyal Soviet citizens, could be constructed in their place.[40]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Gerner & Hedlund (1993). p. 59.

- 1 2 Buttar, Prit. Between Giants. ISBN 978 1 78096 163 7.

- 1 2 Hiden & Salmon (1994). p. 110.

- 1 2 The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by David J. Smith, Page 24, ISBN 0-415-28580-1

- ↑ Mälksoo (2003). p. 83.

- ↑ Mikhail Meltyukhov Stalin's Missed Chance p. 198, available at

- ↑ Pavel Petrov, p. 153

- ↑ Pavel Petrov, p. 154

- ↑ (Finnish) Pavel Petrov at Finnish Defence Forces home page

- ↑ (Russian) documents published from the State Archive of the Russian Navy

- ↑ Pavel Petrov, p. 164

- ↑ The Last Flight from Tallinn at American Foreign Service Association

- ↑ The World Book Encyclopedia ISBN 0-7166-0103-6

- ↑ For Lithuania see, for instance, Thomas Remeikis (1975). "The decision of the Lithuanian government to accept the Soviet ultimatum of 14 June 1940". LITUANUS, Lithuanian Quarterly journal of Arts and Sciences. 21 (4 – Winter 1975). Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ↑ see report of Latvian Chargé d'affaires, Fricis Kociņš, regarding the talks with Soviet Foreign Commissar Molotov in I.Grava-Kreituse, I.Feldmanis, J.Goldmanis, A.Stranga. (1995). Latvijas okupācija un aneksija 1939–1940: Dokumenti un materiāli. (The Occupation and Annexation of Latvia: 1939–1940. Documents and Materials.) (in Latvian). pp. 348–350.

- ↑ for Estonia see, for instance, Tanel Kerikmäe; Hannes Vallikivi (2000). "State Continuity in the Light of Estonian Treaties Concluded before World War II". Juridica International (I 2000): 30–39. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ↑ The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania p.19 ISBN 0-415-28580-1

- ↑ Estonia: Identity and Independence by Jean-Jacques Subrenat, David Cousins, Alexander Harding, Richard C. Waterhouse ISBN 90-420-0890-3

- 1 2 Five Years of Dates at Time magazine on Monday, Jun. 24, 1940

- ↑ The Occupation of Latvia at Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia

- ↑ Germany Over All, TIME Magazine, June 24, 1940

- ↑ nearly 650,000 according to Kenneth Christie; Robert Cribb (2002). Historical Injustice and Democratic Transition in Eastern Asia and Northern Europe: Ghosts at the Table of Democracy. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 83. ISBN 0-7007-1599-1.

- ↑ Stephane Courtois; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07608-7.

- ↑ June 14 the Estonian government surrendered without offering any military resistance; The occupation authorities began...by disarming the Estonian Army and removing the higher military command from power Ertl, Alan (2008). Toward an Understanding of Europe. Universal-Publishers. p. 394. ISBN 1-59942-983-7.

- ↑ the Estonian armed forces were disarmed by the Soviet occupation in June 1940 Miljan, Toivo (2004). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Scarecrow Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-8108-4904-6.

- ↑ Baltic States: A Study of Their Origin and National Development, Their Seizure and Incorporation Into the U.S.S.R. W. S. Hein. p. 280.

- ↑ "The President of the Republic acquainted himself with the Estonian Defence Forces". Press Service of the Office of the President. December 19, 2001. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ↑ (Estonian)51 years from the Raua Street Battle at Estonian Defence Forces Home Page

- ↑ 784 AE. "Riigikogu avaldus kommunistliku režiimi kuritegudest Eestis" (in Estonian). Riigikogu. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ↑ Lohmus, Alo (10 November 2007). "Kaitseväelastest said kurja saatuse sunnil korpusepoisid" (in Estonian). Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ↑ "Põlva maakonna 2005.a. lahtised meistrivõistlused mälumängus" (in Estonian). kilb.ee. 22 February 2005. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ↑ FALSIFIERS of HISTORY (Historical Survey) Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow 1948

- ↑ Childs, David (1977). "The British Communist Party and the War, 1939–41: Old Slogans Revived". Journal of Contemporary History. 12 (2): 237–253. doi:10.1177/002200947701200202. JSTOR 260215.

- ↑ Misiunas & Taagepera 1993, p. 20

- ↑ in addition to the envoys accredited in Baltic countries, Soviet government sent the following special emissaries: to Lithuania: Deputy Commissar of Foreign Affairs Dekanozov; to Latvia: Vishinski, the representative of the Council of Ministers; to Estonia: Regional Party Leader of Leningrad Zhdanov. "Analytical list of documents, V. Friction in the Baltic States and Balkans, June 4, 1940 – September 21, 1940". Telegram of German Ambassador in the Soviet Union (Schulenburg) to the German Foreign Office. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- 1 2 Misiunas & Taagepera 1993, pp. 26–7

- ↑ Attitudes of the Major Soviet Nationalities, Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1973

- ↑ Mangulis, Visvaldis (1983). "VIII. September 1939 to June 1941". Latvia in the Wars of the 20th century. Princeton Junction: Cognition Books. ISBN 0-912881-00-3.

- ↑ Švābe, Arvīds. The Story of Latvia. Latvian National Foundation. Stockholm. 1949.

- 1 2 O'Connor 2003, p. 117

Bibliography

- Brecher, Michael; Jonathan Wilkenfeld (1997). A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan Press. p. 596. ISBN 978-0-472-10806-0.

- Gerner, Kristian; Hedlund, Stefan (1993). The Baltic States and the end of the Soviet Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07570-X.

- Hiden, Johan; Salmon, Patrick (1994) [1991]. The Baltic Nations and Europe (Revised ed.). Harlow, England: Longman. ISBN 0-582-25650-X.

- Mälksoo, Lauri (2003). Illegal Annexation and State Continuity: The Case of the Incorporation of the Baltic States by the USSR. The Netherlands: Martinus Niljhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-2177-6.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003). The History of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 113–145. ISBN 978-0-313-32355-3.

- Rislakki, Jukka (2008). The Case for Latvia. Disinformation Campaigns Against a Small Nation. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2424-3.

- Plakans, Andrejs (2007). Experiencing Totalitarianism: The Invasion and Occupation of Latvia by the USSR and Nazi Germany 1939–1991. AuthorHouse. p. 596. ISBN 978-1-4343-1573-1.

- Wyman, David; Charles H. Rosenzveig (1996). The World Reacts to the Holocaust. JHU Press. pp. 365–381. ISBN 978-0-8018-4969-5.

- Frucht, Richard (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

- Misiunas, Romuald J.; Taagepera, Rein (1993), The Baltic States, years of dependence, 1940–1990, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-08228-1

- O'Connor, Kevin (2003), The history of the Baltic States, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-32355-0

- Petrov, Pavel (2008). Punalipuline Balti Laevastik ja Eesti 1939–1941 (in Estonian). Tänapäev. ISBN 978-9985-62-631-3.

- Hiden, John; Vahur Made; David J. Smith (2008). The Baltic question during the Cold War. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-37100-7.

- Talmon, Stefan (1998). Recognition of governments in international law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826573-3.

- McHugh, James; James S. Pacy (2001). Diplomats without a country: Baltic diplomacy, international law, and the Cold War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31878-6.

Further reading

- Žiemele, Ineta, ed. (2002). Baltic Yearbook of International Law (2001). 1. ISBN 978-90-411-1736-6. ISSN 1569-6456.

- Dawisha, K.; Parrott, B., eds. (June 1997). The Consolidation of Democracy in East-Central Europe. ISBN 978-0-521-59938-2.