Celtic literature

In the strictly academic context of Celtic studies, the term Celtic literature is used by Celticists to denote any number of bodies of literature written in a Celtic language, encompassing the Irish, Welsh, Cornish, Manx, Scottish Gaelic and Breton languages in either their modern or earlier forms.

Alternatively, the term is often used in a popular context to refer to literature which is written in a non-Celtic language, but originates nonetheless from the Celtic nations or else displays subjects or themes identified as "Celtic". Examples of these literatures include the medieval Arthurian romances written in the French language, which drew heavily from Celtic sources, or in a modern context literature in the English language by writers of Irish, Welsh, Cornish, Manx, Scottish or Breton extraction. Literature in Scots and Ulster Scots may also be included within the concept. In this broader sense, the applicability of the term "Celtic literature" can vary as widely as the use of the term "Celt" itself.

For information on the development of particular national literatures, see: Irish literature, Scottish literature, Welsh literature, Literature in Cornish, Breton literature and Manx literature.

Early Celtic literature in Britain

Early Celtic literature

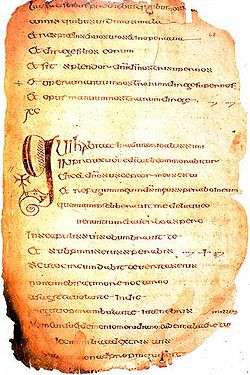

Gaelic language and literature from Ireland became established in the West of Scotland between the 4th and 6th centuries. Until the development of Scottish Gaelic literature with a distinct identity, there was a shared literary culture between Gaelic-speaking Ireland and Scotland. The literary Gaelic language used in Scotland that was inherited from Irish is sometimes known as Classical Gaelic. The Hiberno-Scottish mission from the 6th century spread Christianity and established monasteries and centres of writing. Gaelic literature in Scotland includes a celebration, attributed to the Irish monk Adomnán, of the Pictish King Bridei's (671–93) victory over the Northumbrians at the Battle of Dun Nechtain (685). Pictish, the now extinct Brythonic language spoken in Scotland, has left no record of poetry, but poetry composed in Gaelic for Pictish kings is known. By the 9th century, Gaelic speakers controlled Pictish territory and Gaelic was spoken throughout Scotland and used as a literary language. However, there was great cultural exchange between Scotland and Ireland, with Irish poets composing for Scottish or Pictish patrons, and Scottish poets composing for Irish patrons.[1] The Book of Deer, a 10th-century Latin Gospel Book with early-12th-century additions in Latin, Old Irish and Scottish Gaelic, is noted for containing the earliest surviving Gaelic writing from Scotland.

In Medieval Welsh literature the period before 1100 is known as the period of Y Cynfeirdd ("The earliest poets") or Yr Hengerdd ("The old poetry"). It roughly dates from the birth of the Welsh language until the arrival of the Normans in Wales towards the end of the 11th century. Y Gododdin is a medieval Welsh poem consisting of a series of elegies to the men of the Britonnic kingdom of Gododdin and its allies who, according to the conventional interpretation, died fighting the Angles of Deira and Bernicia at a place named Catraeth in c. AD 600. It is traditionally ascribed to the bard Aneirin, and survives only in one manuscript, known as the Book of Aneirin. The poem is recorded in a manuscript of the second half of the 13th century, and it has been dated to anywhere between the 7th and the early 11th centuries. The text is partly written in Middle Welsh orthography and partly in Old Welsh. The early date would place its oral composition to soon after the battle, presumably in the Hen Ogledd ("Old North") in what would have been the Cumbric variety of Brythonic.[2][3] Others consider it the work of a poet in medieval Wales, composed in the 9th, 10th or 11th century. Even a 9th-century date would make it one of the oldest surviving Welsh works of poetry.

The name Mabinogion is a convenient label for a collection eleven prose stories collated from two medieval Welsh manuscripts known as the White book of Rhydderch (Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch) (c. 1350) and the Red Book of Hergest (Llyfr Coch Hergest) (1382–1410). They are written in Middle Welsh, the common literary language between the end of the eleventh century and the fourteenth century. They include the four tales that form Pedair Cainc y Mabinogi ("The Four Branches of the Mabinogi"). The tales draw on pre-Christian Celtic mythology, international folktale motifs, and early medieval historical traditions. While some details may hark back to older Iron Age traditions, each of these tales is the product of a highly developed medieval Welsh narrative tradition, both oral and written. Lady Charlotte Guest in the mid-19th century was the first to publish English translations of the collection, popularising the name "Mabinogion" at the same time.

No Cornish literature survives from the Primitive Cornish period (c. 600–800 AD). The earliest written record of the Cornish language, dating from the 9th century, is a gloss in a Latin manuscript of the Consolation of Philosophy, which used the words ud rocashaas. The phrase means "it (the mind) hated the gloomy places".[4][5]

Revival literature in non-Celtic languages

The Gaelic Revival reintroduced Celtic themes into modern literature. The concept of Celticity encouraged cross-fertilisation between Celtic cultures.

There have been modern texts based around Celtic literature. Bernard Cornwell writes about the Arthurian legends in his series The Warlord Chronicles. Other writers of Celtic literature in English include Dylan Thomas and Sian James.

Themes from Celtic Literature within Arthurian Romances

Within many Arthurian texts one can see the influence of Celtic literature and folklore. Examples of Arthurian legends with these components are Marie de France’s Lanval, the tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and in Perceval De Troyes, The Story of the Grail. In his work “Celtic Elements in ‘Lanvnal ‘and Graelent’,” Cross claims that Lanval is a medieval narrative called a “Brenton Lay” which is a work that contains themes from Celtic tradition.[6] Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is said to contain traditions from early Irish Lore, such as the Beheading test.[7] In addition to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Lanval, Perceval, The Story of the Grail contains a combination of these two Celtic themes. While there are other tales whose Celtic elements can be examined, these three are most likely among the best examples.

A major aspect of Celtic literature within “Lanval” is the theme itself, the story that a fairy mistress falls in love with a mortal. In Lanval, an unpopular knight of the court becomes the lover of a mysterious and otherworldly woman. Though he breaks his promise to keep their love a secret, he is eventually reunited with her (Marie de France 154-167). Cross states that, “The influence of one medieval romance of Celtic stories involving both the fairy mistress and the Journey to the Otherworld has long since been recognized”.[8] While we are never told whether or not Lanval’s lover is a fairy, it is most certain that she is a woman of supernatural origin. There is a similar example to the story of “Lanval” in the Irish story, “Aidead Muirchertaig maic Erca”.[9] One of the only differences between the original Irish stories and that of “Lanval” is the fact that Marie de France’s story is more Christianized and erases any overtly Pagan elements. There are also many other examples of a fairy mistress bestowing favor upon a mortal man within Irish folklore. After providing many examples of this theme within early Celtic literature, Cross states that, “Those given (examples) above demonstrate beyond the possibility of doubt that stories of fee who hanker after mortal earth-born lovers and who visit mortal soil in search of their mates existed in early Celtic tradition…”.[10]

In “Sir Gaiwan and the Green Knight” the theme of the Beheading Test is prevalent. According to Alice Buchanan’s article: “The Irish Framework of Sir Gawin and the Green Knight,” Buchanan states: “the theme of Beheading texts, which occurs in Arthurian Romances, French, English, and German, from about 1180 – 1380, is derived from an Irish tradition actually existent in a MS. Written before 1106”.[11] In “Sir Gaiwan and the Green Knight,” it’s Gawain’s head which is at stake. This is where the “Beheading Game” comes into place. This is when a supernatural challenger offers to let his head be cut off in exchange for a return blow.[12] In the journal article, “The Medieval Mind in ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’ author Dean Loganbill states that the first text in which the “Beheading Game” is shown is in the Middle Irish tale of Bricriu’s Feast. However, the Gawain poets put a spin on the simple beheading game by linking it with themes of truth. The article also notes that it is also frequently stated that the Gawin poet was the first to unite the beheading game with the themes of temptation.[13]

The Celtic motifs of the “Beheading Game” and temptation are also apparent in the first continuation of the French romance, Perceval Chretien de Troyes, The Story of the Grail—A story by Chretien which is believed to parallel Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in plot (Grant 7). The early French character known as Caradoc is thought to be one of the first Arthurian characters to use the beheading game as a means to figure out whom his birth father is. The theme of temptation falls into place as many characters fall into the trap of seduction by other people and also by wizards and other mythological creatures that are known to be of Celtic origin (Chrétien).

Celtic mythology also displays itself in “Sir Gaiwain and the Green Knight.” Looking at Gaiwan, we see him as the leading leader at the Primary Table in which he is tested by the rulers of the otherworld in terms of his fitness for fame in this world and the next. With this in mind, the “rulers of the otherworld” have a mythical nature to them; there are references to sun gods, and old and new gods. It might seem as though that would be taking the mythological concept and simplifying it, however in Celtic mythology, the traits of individual and groups of gods are not so distinct.[14]

See also

Resources

Buchanan, Alice. “The Irish Framework of Gawain and the Green Knight.” PMLA. 2nd ed. vol. 47. Modern Language Association, 1932. JSTOR. Web. 9 Oct. 2012.

Chrétien de Troyes; Bryant, Nigel (translator) (1996). Perceval, the Story of the Grail. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer.

Cross, Tom P. “The Celtic Elements in the Lays of ‘Lanval’ and ‘Graelent’.” Modern Philology. 10th ed. vol. 12. The University of Chicago Press, 1915. JSTOR. Web. 8 Oct. 2012.

France, Marie de. “Lanval.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Gen. ed. Stephen Greenblatt. 9th ed. Vol. 1. New York: Norton, 2012. 154-167. Print.

Grant, Marshal Severy. ""Sir Gawain and the Green Knight" and the Quest for the Grail: Chretien De Troyes' "Perceval", the First Continuation, "Diu Krone" and the "Perlesvaus"." Yale University, 1990. United States -- Connecticut: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT). Web. 24 Oct. 2012.

Loganbill, Dean. “The Medieval Mind in ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’.” The Bulletin of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association. 4th ed. vol. 26. Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association, 1972. JSTOR. Web. 8 Oct. 2012.

References

- ↑ Clancy, Thomas Owen (1998). The Triumph Tree: Scotland's Earliest Poetry AD 550–1350. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 0862417872.

- ↑ Elliot (2005), p. 583.

- ↑ Jackson (1969)—the work is titled The Gododdin: the oldest Scottish poem.

- ↑ Oxford scholars detect earliest record of Cornish Archived 25 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sims-Williams, P., 'A New Brittonic Gloss on Boethius: ud rocashaas', Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 50 (Winter 2005), 77–86.

- ↑ Cross, Tom P. “The Celtic Elements in the Lays of ‘Lanval’ and ‘Graelent’.” Modern Philology. 10th ed. vol. 12. The University of Chicago Press, 1915, p.5. JSTOR. Web. 8 Oct. 2012.

- ↑ Buchanan, Alice. “The Irish Framework of Gawain and the Green Knight.” PMLA. 2nd ed. vol. 47. Modern Language Association, 1932. JSTOR. Web. 9 Oct. 2012.

- ↑ Cross, Tom P. “The Celtic Elements in the Lays of ‘Lanval’ and ‘Graelent’.” Modern Philology. 10th ed. vol. 12. The University of Chicago Press, 1915, p.10. JSTOR. Web. 8 Oct. 2012.

- ↑ Cross, Tom P. “The Celtic Elements in the Lays of ‘Lanval’ and ‘Graelent’.” Modern Philology. 10th ed. vol. 12. The University of Chicago Press, 1915, p.11. JSTOR. Web. 8 Oct. 2012.

- ↑ Cross, Tom P. “The Celtic Elements in the Lays of ‘Lanval’ and ‘Graelent’.” Modern Philology. 10th ed. vol. 12. The University of Chicago Press, 1915, p.15. JSTOR. Web. 8 Oct. 2012.

- ↑ Buchanan, Alice. “The Irish Framework of Gawain and the Green Knight.” PMLA. 2nd ed. vol. 47. Modern Language Association, 1932, p. 315. JSTOR. Web. 9 Oct. 2012.

- ↑ France, Marie de. “Lanval.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Gen. ed. Stephen Greenblatt. 9th ed. Vol. 1. New York: Norton, 2012, p. 160. Print.

- ↑ Loganbill, Dean. “The Medieval Mind in ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’.” The Bulletin of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association. 4th ed. vol. 26. Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association, 1972, p. 123. JSTOR. Web. 8 Oct. 2012.

- ↑ Loganbill, Dean. “The Medieval Mind in ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’.” The Bulletin of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association. 4th ed. vol. 26. Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association, 1972, p. 124. JSTOR. Web. 8 Oct. 2012.

External links

- Aberdeen University Celtic Department Courses and information on the literatures of the Celtic countries

- Celtic Literature Library

- The Celtic Literature Collective

- Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT) - many old Irish tales and histories available online