Central American Seaway

The Central American Seaway, also known as the Panamanic Inter-American and Proto-Caribbean Seaway, was a body of water that once separated North America from South America. It formed in the Mesozoic (200–154 Ma) during the separation of the Pangaean supercontinent, and closed when the Isthmus of Panama was formed by volcanic activity in the late Pliocene (2.76–2.54 Ma).

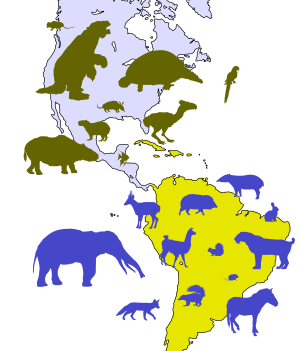

The closure of the Central American Seaway had tremendous effects on oceanic circulation and the biogeography of the adjacent seas, isolating many species and triggering speciation and diversification of tropical and sub-tropical marine fauna.[1] The inflow of nutrient-rich water of deep Pacific origin into the Caribbean was blocked, so local species had to adapt to an environment of lower productivity.[2] It had an even larger impact on terrestrial life. The seaway had isolated South America for much of the Cenozoic, allowing the evolution of a wholly unique diverse mammalian fauna there; when it closed, a faunal exchange with North America ensued, leading to the extinction of many of the native South American forms.[3][4]

Evidence

The evidence for when the Central American landmass emerged and the closing of the Central American Seaway can be divided into three categories. The first is the direct geologic observation of crustal thickening and submarine deposits in Central America. The second is the Great American Interchange of vertebrates between North and South America which required a continuous land bridge across the two areas for the organisms to travel along with a climate that was very different than the climate today. Lastly is the development of differences in marine assemblages and their isotopic signatures in the Caribbean from those in the Pacific.[5][6] The Great American Interchange gives climate change the role as an arid Central American environment was needed in order for vertebrates to go from the savannas across the Panama region. The Central American Seaway was closed by the elevation of the Central American Isthmus which is proposed to have occurred three and a half to five million years ago. The closing of the Central American Seaway is also supported by the evolution of taxa on different sides of the Central American Isthmus along with the different histories of the oceans on either side of the isthmus.

Consequences

The closing of the seaway allowed a major migration of land mammals between North and South America or The Great American Interchange. This allowed the entrance of species of mammals such as sloths, cats, horses, elephants and camels to migrate from North America to South America. It is believed that the animals that were able to cross the land bridge were savannah animals as the rain forest animals would not be able to cross Central America. There is much controversy about glacial and interglacial climates in South America. Research shows that vegetation in most of the Amazon basin has changed a very small amount since glacial times. It is also believed that the area was more of a savannah during glacial times, but it is believed that the area is quite the same. Predicted connections between a closed seaway and glaciation are causation for a very different North Atlantic Ocean circulation having an effect on the surrounding atmospheric temperatures thus permitting South American organisms to tolerate the North American Climate. The emergence of South American organisms is due to the widening of that organisms' ecological niche. The niche concept is that if an area supports an organism's need for survival then it is more likely to live there. The Panama Isthmus is believed to have emerged due to the appearance of glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere. The appearance of the isthmus is then credited to changing the current therefore affecting the atmosphere causing the recurrence of ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere and is believed to be the cause of the Ice Age. The emergence of the isthmus caused a reflection of the westward-flowing North Equatorial Current northward and enhanced the northward-flowing Gulf Stream.[7]

See also

- Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation

- Great American Interchange

- North Atlantic Deep Water

- Paleoceanography

References

- ↑ Lessios, H.A. (December 2008). "The Great American Schism: Divergence of Marine Organisms After the Rise of the Central American Isthmus". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. Palo Alto. 39: 63–91. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095815.

- ↑ Jain, S.; Collins, L. S. (2007-04-30). "Trends in Caribbean Paleoproductivity related to the Neogene closure of the Central American Seaway". Marine Micropaleontology. 63 (1–2): 57–74. doi:10.1016/j.marmicro.2006.11.003.

- ↑ Simpson, George Gaylord (1980). Splendid Isolation: The Curious History of South American Mammals. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 266. ISBN 0-300-02434-7. OCLC 5219346.

- ↑ Marshall, L. G. (July–August 1988). "Land Mammals and the Great American Interchange" (PDF). American Scientist. 76 (4): 380–388. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ http://www.colorado.edu/geolsci/faculty/molnarpdf/2008Paleoc.CentralAmericanSeaway.pdf

- ↑ Molnar, Peter. "Closing of the Central American Seaway and the Ice Age: A critical review" (PDF).

- ↑ "Tertiary Period | geochronology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2015-12-07.