Charles Philipon

Charles Philipon (19 April 1800 – 25 January 1861). Born in Lyon, he was a French lithographer, caricaturist and journalist. He was the editor of the La Caricature and of Le Charivari, both satirical political journals.

Early years

Charles Philipon came from a small, middle-class, Lyons family. His father, Étienne Philipon, was a hatter and wallpaper manufacturer. He enthusiastically welcomed the revolution of 1789. According to Pierre Larousse[1] his ancestors included Manon Roland, Armand Philippon, and Louis Philipon de La Madelaine.

After attending school in Lyons and Villefranche-sur-Saône, Charles Philipon studied drawing at the École Impériale des Beaux-arts de Lyon. He left his hometown in 1819 to work under the artist Antoine Gros in Paris but returned at his father's behest in 1821 to join the family business, designing fabric for three years. Though this activity did not suit him, it left its mark on his subsequent work. During hard economic and social times in 1824, he took part in a Lyons carnival parade that was deemed seditious; he was arrested, but ultimately charges were dropped.

Charles Philipon finally left Lyon for Paris where he reunited with old friends from the workshop Gros. One of them, Charlet, a renowned artist, took him under his wing and introduced him to lithography, a technique spreading in France in the 1820s. Philipon found employment as a lithographer and artist drawing for picture books and fashion magazines; he showed invention by converting a lead chimney to a lithographic machine . He bonded with the Liberals and satirists of the day, attended the Grandville workshop(1827), and two years later joined forces with the creators of the newspaper La Silhouette, on which he worked as an editor and designer.

While Philipon's financial contribution to the company was small, his editorial contribution seems to have focused on the organization of the lithographic department, which gave the paper its originality inasmuch as the same importance was given to the illustration as to the text. Whereas La Silhouette previously had no definite political line, by July 1830 it had developed a more aggressive approach. It is in this journal that on April 1, 1830, Philipon published the first political cartoon, " Charles X Jesuit ."

On 15 December 1829 Philipon sent his son and business partner, Gabriel Aubert, to set up the Aubert publishing house Aubert, competing with other printing shops in Paris. The Veronique Dodat pass, where the publishing house could be found, was to become in the following years a "place of breathtaking [commercial] war" (Ch. Lèdre ) .

Birth of a business

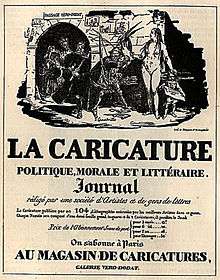

After the revolution of July 1830, Philipon published Nov. 4 of that year an illustrated weekly under the title Cartoon moral, religious, literary and scenic.[2] Sold by subscription only, it has four pages of text and two lithography in a larger than Silhouette format. Associated with the creation of Philipon newspaper, Honoré de Balzac wrote in the prospectus and gave it under various pseudonyms thirty articles until February 1832[3] and testing Small Miseries of married life in 1830. The journal is primarily designed as an elegant illustrated magazine, the neat drawings, printed on vellum paper. The lithographs are printed on separate text and tear sheets . At first, La Caricature adopts a non-political attitude before turning in spring 1832 in opposition to the plan member of the July Monarchy .

On 1 December 1832 Philipon publishes Le Charivari, a daily illustrated with four pages in a smaller Caricature format. More varied and more "popular" than its predecessor, it is not limited to political caricature. Charivari is intended, according to the prospectus, a " comprehensive overview which recur constantly , by pencil and pen , all the various aspects of this kaleidoscopic world in which we live." The lithographs are of lower quality than in La Caricature, but better integrated into the text. Thereafter, the presentation of Charivari bring significant changes.

Owner of these two newspapers, Philipon has the full control for both administrative and physical part for editorial and artistic part . He chooses his collaborators, dealing with suppliers in the market as well as financial management. In an obituary published in 1862, Nadar the credits of " extraordinary lucidity in business " coupled with " inexhaustible fertility of invention and means ".[4] Employer of his artist friends, it defines the objectives with them, suggest topics, coordinating text and lithography. He does not hesitate to ask for changes to avoid censorship. To ensure editorial consistency, writing is reduced to a small team of highly dedicated journalists (in February 1834, they are seven Philipon included).[5]

The testimony of his contemporaries emphasize charisma Philipon. He was "the soul of the company". According to Champfleury, "he led a large group of pencils, called him the young men breathed their flame, gave ideas to those who did not have".[6] If draws little himself, he puts all his enthusiasm in lithographs. When Silhouette disappears early January 1831, he has on the market a near monopoly. In 1836, a third of lithographs published in the capital will come from Aubert's house.[7] However, the company has retained its family character, besides his son, Gabriel Aubert, especially his sister, Marie- Françoise Aubert, it contributed effectively.

Intense years (1830-1835)

The campaign against Louis-Philippe (1830-1832)

In the fall of 1830 Philipon, as supporters of the Revolution of July, expect a lot of the new regime . The first issues of La Caricature are free from political office . "Firstly , drawings stood outside politics, merely represent popular or familiar scenes , accidentally attacking men and things thrown down by the heroic revolution of July ".[8] Editor and friend Philipon, Balzac contributed extensively in this period, signing his articles under various pseudonyms, as was often the case. The persistence of anti-clericalism already present there in Silhouette and manifests itself in texts such as illustrations . The memory of Napoleon still alive.

In late December 1830 - early 1831, the tone changes . In January, a lithograph Decamps, Freedom to post ( La Caricature, January 27, 1831 ), gives the signal. Attached to the " pole of shame ", Françoise Freedom, " was born in Paris in 1790 ," pay " by order of the provost court" [...] " for the crime of rebellion in the days of 27, 28, 29 July in 1830 . " This " super board " refers explicitly to the law of December 4, 1830 that restores stamp duty and security for newspapers. It will be followed in March 1831 by another lithograph Decamps, Freedom (Françoise Désirée ) daughter of the people, born in Paris July 27, 1830, where a girl symbolizing freedom is held in check by a group of men who try to remember (La Caricature, March 3, 1831 ), they represent the party of resistance opposed to reform. In the foreground we recognize without difficulty "citizen king " and the serene face, it seems to control the situation.[9]

From that moment, the caricature is more political satire and gradually spread to all sections . She does not hesitate to take to the king and his ministers. This is not the "Charter", abused, but the "burden" that will now be a vérité.[10] Speaking later to a friend, Philipon wrote: " The Golden [ consensus ] age did not last long , you will see, after a dozen numbers [ La Caricature ] dawning political cartoons , soft first, very aggressive , and you will see it come back more often , more often, and more intense, until it occupies only the newspaper and become ruthless ".[11]

In addition to the long Caricature ( 17 November 1831 ) sets out the main Philipon grievances made to the government . In addition to the new laws " as stringent as under Charles X " and jeopardize its business release ( less than two years, La Caricature will incur seven trials and four convictions, not counting the many foreclosures that penalize its trading ) he denounces the end of liberal institutions, non- compliance with the Charter, profiteering, the dropping of Poland, illustrated by a lithograph of Grandville and Forest ( " order reigns in Warsaw» Aubert, September 20, 1831 ).[12]

Alienation vis-à- vis the regime is expressed in a cartoon Philipon published as foam Aubert July by the House ( 26 February 1831 ) . Better known as The soap bubbles, it shows Louis -Philippe carelessly blowing the bubbles that shows the unfulfilled promises freedom of the press, popular elections, mayors elected by the people, more than sinecures etc.[13] Prosecuted for insulting the king, Philipon will eventually acquitted. He returned a few months later with another lithograph, known as The Cosmetic repair (La Caricature, June 30, 1831 ), where the king is represented symbolically mason erasing the traces of the July Revolution.[14] He returned for trial in the Assize Court.

Trial and conviction

The " coup de theater " occurs at the hearing on 14 November 1831 when facing the judges, Philipon sure to be condemned, plays his all and shows a deft that " everything can look like the king " argument, and that it can not be held responsible for this resemblance . And illustrate its defense by the metamorphosis of his portrait pear.[15] These are the famous " croquades made at the hearing on 14 November 1831 ." Success is immense : " What I had foreseen happened . The people seized by a mocking image, a simple image design and simple shape , began to imitate this wherever he found a way to make charcoal image smearing , scratching a pear. Pears soon covered all the walls of Paris and spread to all parts of the walls of France ".[16] More broadly, the event was a tribute to the art of caricature ( Champfleury Philipon called it the " Juvenal caricature ") that transforms the target to reveal the essential features .

Beyond the person of the king, the "pear" symbolized the regime and its cronies . It was taken extensively by artists working with Philipon, including Daumier ( A huge pear hanging by the commoners ), Grandville ( The Birth of the Juste- Milieu ) Travies (Mr. Mahieux poiricide ) Bouquet ( Pear and pips) . A peak will be reached when Philipon publish the Project Atonement pear monument erected on the Place de la Revolution, precisely the place where Louis XVI was guillotined (La Caricature, June 7, 1832 ) .[17] He will be charged with inciting regicide .

At the end of his trial before the Assize Court, Philipon was convicted of " contempt of the king's person ." Arrested Jan. 12, 1832, he had served six months in prison and pay a fine of 2,000 francs, which were added seven months related to other grounds of conviction. He was transferred to the prison Sainte- Pelagie, and home health Dr. Pinel, where the regime is more favorable.

The final break with the July Monarchy occurred on 5 and 6 June 1832, at the funeral of General Lamarque, which turned into rebellion harshly repressed . Philipon had just publish and sign the " Project for a monument pear Atonement ." Fearing for his life, he hides in Paris until the end of the siege. He returned to Sainte- Pelagie 5 September 1832 and finally released from prison Feb. 5, 1833 .

By bitterness of a regime that " persecuted " and probably under the influence of contacts in prison, his positions had firmed . After hoped a "liberalism compatible with monarchy", it became Republican in itself. But he had never ceased to be ? Philipon proclamation published in La Caricature ( 27 December 1832 ), true profession of faith, leaves no doubt about it : " We repeat, we are what we were there twelve years , frank and pure republicans . Who says otherwise is an impostor who says behind us in ambiguous terms is a coward . "

Republican commitment (1833-1835)

At the time of his first political cartoons, Philipon had already established contacts with Republican circles . Number of artists who gravitated around him were republican conviction or at least sympathizers. From November 1831 to March 1832, a list of subscriptions is launched from La Caricature, and a second call is made a year later in Le Charivari without much success, the economic situation there is hardly suitable . From 1833 to tighten the links . In La Caricature 11 April of that year, Philipon publishes Bluebeard, white and red by Grandville and Desperet, an openly militant lithography. The advent of the republic is announced in the manner of a tale by Perrault : "The press , my sister , do you see anything coming ? " . While Louis -Philippe, back ( a subterfuge designed to avoid censorship ), is about to stab the constitution, the herald symbolizing the press carries on its banner the word " Republic " and his trumpet and National Tribune, title two newspapers of the Republican opposition.

In 1834, these links are strengthened. To keep a few examples,[18] Le Charivari made fundraising for several republican associations. The same year, Philipon is among the founders of the Republican Journal ( February 1834 ) which he owns shares . At the Hotel Colbert where offices are located Charivari, two Republican newspapers, The National and The Common sense will also have their neighborhood. This is where stood Gregory, the most prominent Republican printer Paris, which Aubert and Philipon associated as shareholders.

These expressions of solidarity are reflected in the lithographs in which the figure of the proletariat is at the center of several caricatures : Ouch therefore proletarian ! by Benjamin Roubaud ( Le Charivari, December 1, 1833) and Do not rub it ! Daumier, published in Monthly Association ( June 20, 1834 ), a supplement created by Philipon to train, by voluntary subscription, a reserve fund . In this lithograph, considered by Philipon as " one of the best political sketches made in France ", a typographer full force at the forefront defies away frail figures of Louis -Philippe and Charles X. However, Philipon remain a Republican "patriot" in the tradition of 1789, more sensitive to political freedom only if the working masses.

Commitment can not be denied the uprisings harshly repressed Lyon (April 9 ) and Paris (13 April). Several lithographs emerge, including Hercules winner Travies ( La Caricature, 1 May 1834) and especially Rue Transnonain Daumier ( Monthly Association, September 24, 1834 ), which refers to the killing by troops of the inhabitants of this street 15 April 1834.[19] "This is not a caricature ," says Philipon, " it is not a burden , it's a bloody page of our modern history page drawn by a strong hand and dictated by an old indignation " ( La Caricature, October 2, 1834 ) .

July 28, 1835, bombing of Fieschi has immediate consequences : arrest of Armand Carrel at the Hotel Colbert, ransacking offices Charivari, an arrest warrant is issued against Philipon and that Desnoyers prefer to escape and hide . The day before the attack, had published Philipon red number Charivari, real firebrand with as an article a list of men, women and children killed by the troops and the National Guard since 1830. He was accompanied by a lithograph Travies ironically titled " Personification of the sweetest and most humane system " ( Le Charivari, July 27, 1835 ), where the body of the "patriots" murdered forms an image of Louis-Philippe back.[20] Philipon be accused of " moral complicity " in the attack.

On 5 August 1835, new press laws are presented in the House. At the meeting of August 29, Thiers said: " There is nothing more dangerous [...] that infamous caricatures, seditious designs , there is no more direct provocation to attack " ( The universal monitor, August 30, 1835 ) . Caricature ceased publication . In November 1835, Le Charivari is sold for a pittance, but Philipon canned Officer until 1838. Taking stock of five years, he wrote : "I started November 4, 1830 the country's liberal illusions and I arrived in September 1835 in the kingdom of the saddest realities".[21]

From political cartoon to satire of manners (after 1835)

If the " September Laws " mark the end of the political cartoon in his " vehement " version Philipon not remains active . In addition to the reissue of La Caricature Caricature became Provisional (1838), also called " non-political cartoon ," he published in Le Charivari series Robert Macaire ( 1836-1838 ), the Museum to laugh designs for all cartoonists Paris (1839-1840), the Museum or comic store Philipon (1843), Paris comic (1844), Le Journal pour rire ( 1848-1855 ), became the fun Journal (1856 ), where the proceeds essentially comic satire manners .

The purpose of this "library for fun " is to distract and entertain through the creation of " social types " representative, the physiologies, very popular with the public.[22] The most emblematic kinds were illustrated in particular by Daumier ( Ratapoil, Robert Macaire ) Travies ( M.Mayeux ), Henry Monnier (Joseph Prudhomme ) Gavarni (Thomas Vireloque ) . Vogue physiologies was conducive to Aubert House : February 1841 to August 1842, she published thirty to two different physiologies representing three quarters of production in this period.[23]

However, it is not always easy to disentangle the social satire of political satire . In this regard, the series of Robert Macaire is highly significant . Composed and drawn by Daumier about ideas and legends Philipon, all met in volume under the title Les Cent and Robert Macaire (1839) . The large drawings are reduced and accompanied by a comic and narrative written by journalists Alhoy Maurice and Louis Huart . Emphatically presented as an avatar of Don Quixote and Gil Blas, the character of Robert Macaire,[24] in tandem with the naive Bertrand, embodies in its facets and multiple roles a social type characterized by the term " floueur " master diddle all kinds and emblem dominated by the interest and profiteering society ( Marx refer to Louis-Philippe as to " Robert Macaire on his throne "). This " high comedy " that offers the company a particularly cynical and ruthless image is reminiscent of the Human Comedy of Balzac, she would somehow pendant for caricature.

In the same period, Philipon publishes The Floueur (1850 ), the first series of the Library for fun, the Anglo- French Museum ( 1855-1857 ) in collaboration with Gustave Doré, Aux proletarians (with Agénor Altaroche, 1838) and parody wandering Jew ( Louis Huart, 1845), inspired by the work of Eugène Sue .

La Silhouette

In October 1829 Philipon launched a career in journalism as a co-founder of La Silhouette. He made a minor financial investment and became a contributor without final editorial control. La Silhouette was the first French newspaper to regularly publish prints and illustrations, giving them equal or greater importance than the written text. Each issue satirized political and literary events of the day and included lithographs by the best-known graphic artists in Paris.

La Silhouette was published from 24 December 1829 to 2 January 1831. It became the prototype for similar publications published in France throughout the 19th century. La Silhouette was initially known as a moderate journal in a time of intense political debate. Some of the staff had been jailed for publishing works critical of the government while others held more conservative views. Over time, the publication's editorial sympathies became increasingly radical.

Strict government censorship prevented La Silhouette from publishing caricatures aimed directly at politicians – except for a small woodcut of the king (Charles X of France) by Philipon that was surreptitiously inserted within the text of 1 April 1830 issue. The newspaper had never included engravings in this way before and it was overlooked by the censors who were concentrating on the issues's lithographs. The publication caused a scandal – with an intensity that reflected the rarity of political caricature before the Revolution – and the editor was eventually sentenced to six months in prison and fined 1,000 francs. Philipon, who had carefully left the caricature unsigned, escaped the scandal's repercussions.

The censors were circumvented in later issues when the editors wrote bitterly critical partisan commentaries and attached them to seemingly innocuous images. In the May and June issues of 1830, this tactic was used to address a variety of political themes through a series of animal scenes by JJ Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard). In an issue that immediately preceded the July Revolution, Honoré Daumier contributed a non-specific battlefield image that was given an explicit political message by an editor.

He was the director of the satirical political newspapers La Caricature and of Le Charivari which included lithographs by some of France's leading caricaturists including JJ Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard), Honoré Daumier, Paul Gavarni, Charles-Joseph Traviès, Benjamin Roubaud and others. The artists would often illustrate Philipon's themes to create some of France's earliest political cartoons.

He died in Paris at the age of 61.

Gallery

Moeurs Aquatiques. Un Rapt by JJ Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard).

Moeurs Aquatiques. Un Rapt by JJ Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard). Le juste milieu by Charles Philipon

Le juste milieu by Charles Philipon Advertisement for La Caricature, Politique, Morale et Littéraire Journal. Illustration by JJ Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard).

Advertisement for La Caricature, Politique, Morale et Littéraire Journal. Illustration by JJ Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard).

References

- ↑ Grand dictionnaire universel du s-XIXe, Éd. Slatkine, 1982, 17 vol.

- ↑

- ↑ Balzac et Philipon associés, Exposition-dossier à la Maison de Balzac, 23 juin-23 septembre 2001.

- Analyse de l'œuvre Projet du monument expia-poire... de

- ↑ Article nécrologique repris par Champfleury dans Histoire de la caricature moderne, p. 271 et suiv.

- ↑ Desnoyers, Altaroche, Cler, un critique d'art et deux critiques littéraires. David S.Kerr, Caricature and French political culture 1830-1848, Clarendon Press, 2000, p. 30.

- ↑ Champfleury, Histoire de la caricature moderne, p. 26.

- ↑ Kerr, op. cit., p. 59.

- ↑ Pierre Larousse, Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle, op. cit.

- ↑

- ↑ Le Juste Milieu, lithographie de Philipon, non datée.

- ↑ Lettre du 7 juillet 1846 à Roslje, dans : Carteret, Le Trésor du bibliophile romantique et moderne, t. III, p. 124.

- ↑ Déclinée plus tard par ces mêmes artistes (« L'ordre public règne aussi à Paris », Aubert, 1 octobre 1831), puis par Traviès (« L'ordre le plus parfait règne aussi à Lyon », La Caricature, 5 janvier 1832).

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2004-03-21. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Lettres du 7 juillet 1846 à Roslje, Carteret, op. cit., p. 126).

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-06-05. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ See Kerr, op.cit, p. 100 et suivantes.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Lettres à Rosalje du 7 juillet 1846, Carteret, op.cit., p. 124.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-06-05. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ James Cuno, « Charles Philipon, La Maison Aubert, and the business of caricature in Paris, 1829-41 », Art Journal, 1983(4)353.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-06-05. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Philipon. |