Cherchell

| Cherchell شرشال | |

|---|---|

|

Cherchell's fountain place | |

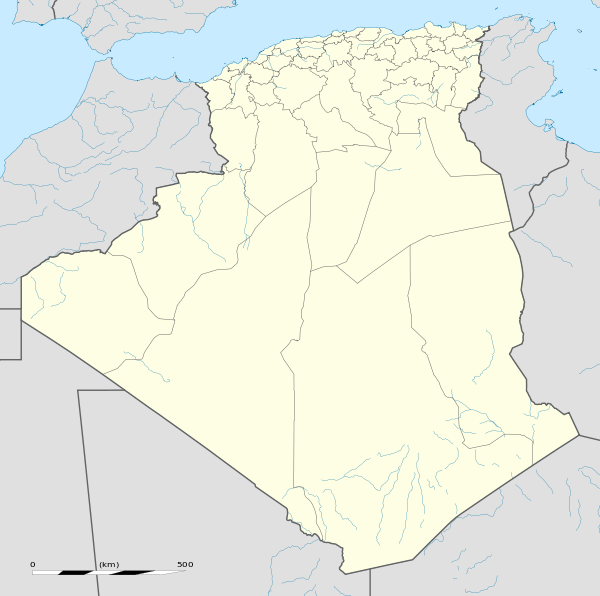

Location of Cherchell in the Tipaza Province | |

Cherchell Location of Cherchell in the Tipaza Province | |

| Coordinates: DZ 36°36′36″N 2°11′48″E / 36.61000°N 2.19667°ECoordinates: DZ 36°36′36″N 2°11′48″E / 36.61000°N 2.19667°E | |

| Country | Algeria |

| Province | Tipaza |

| District | Cherchell |

Cherchell (older Cherchel, Arabic: شرشال) is a seaport town in the Province of Tipaza, Algeria, 55 miles west of Algiers. It is the district seat of Cherchell District. In 1998 it had a population of 24,400.[1]

History

Antiquity to the 4th century AD

Phoenicians from Carthage founded a town at Cherchell around 400 BC, in an area on the northern Maghreb littoral 100 km west of Algiers. Established as a trading station, the city was originally known as Iol or Jol.

Cherchell became a part of the kingdom of Numidia under Jugurtha, who died in 104 BC. It served as a key city for the polity's Berber monarchy and generals. The Berber Kings Bocchus I and Bocchus II lived there, as occasionally did other Kings of Numidia. Iol was situated in an area called Mauretania, which was then a part of the Numidian kingdom.

During the 1st century BC, due to the city’s strategic location, new defences were built.

The last Numidian king was Juba II; his wife was the Greek Ptolemaic princess Cleopatra Selene II, daughter of Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra of Egypt. In 29 BC, Roman emperor Augustus reorganized the area, appointing Juba king of the client kingdom Mauretania, which included western Numidia. The capital was established at Iol, renamed Caesarea or Caesarea Mauretaniae, in honor of the emperor.

Juba and Cleopatra did not just rename their new capital, they rebuilt the town as a typical Greco-Roman city in fine Roman style, on a large, lavish and expensive scale. The town design consisted of street grids, and included a theatre, an art collection, and a lighthouse similar to the one at Alexandria. Caesarea was rebuilt in a rich mixture of ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman architectural styles. The monarchs are buried in the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania which can still be seen. The seaport capital and its kingdom flourished during this period, with most of the population being of Greek and Phoenician origin with a minority of Berbers. Caesarea remained a significant power center under Numidian rule, with |Greco-Roman civilization as a veneer, until 40 CE, when its last monarch Ptolemy of Mauretania was assassinated on a visit to Rome. The murder of Ptolemy set in motion a series of reactions resulting in a devastating war with Rome.

In 44, after a four-year revolt, the capital was captured and Roman Emperor Claudius divided the Mauretanian kingdom into two Roman provinces. The province of which Caesarea became the capital was called Mauretania Caesariensis. The city itself was settled with Roman soldiers and was given the rank of a colonia, and so was also called Colonia Claudia Caesarea.

In later centuries, the Roman population expanded, as did the Berber population, resulting in a mixed Greco-Phoenician, Berber, and Roman population. The city featured a hippodrome, amphitheatre, basilica, numerous Greek temples and Roman civic buildings.[2] During this heyday, the city had its own school of philosophy, academy, and library. As a significant city of the Roman Empire it had trading contacts across the Roman world. Subsequently, the town was the birthplace of the Roman Emperor Macrinus and Greek grammarian Priscian.

Additionally, the city also featured a small but growing population of converted Christians and was noted for the religious debates and tumults which featured the hostility of Roman public religion toward Christians. Caesarea thus has its own martyred Catholic saint, Marciana (her feastday is on 9 January). This virgin martyr was accused of vandalizing a statue of the goddess Diana. After being tortured, Marciana was gored by a bull and mauled by a leopard in the amphitheatre at Caesarea. By the 4th century, the conversion of the population from pagan to Christian beliefs resulted in nearly half of the population being Christianized. The Christians of the city named bishops between about 314 and 484 AD.

During the decline of Roman empire

In the 5th century, the city remained an extremely loyalist power for the Roman Empire. Additionally, the city's elite held considerable control of international trade. Although the city had been in a state of stagnation for over a hundred years and had even lost population as most cities in the Roman Empire, it still remained much as it had been since establishment. Consequently, the Roman Empire relied on much of its North African dominion for essential food stuffs, luxury goods and a not insignificant number of elite rulers.

Thus, in the waning days of the Empire it became a target of the Vandals and their expedition to bring down their Imperial opponents. A Vandal army and fleet burnt the town and fortified many of its old magnificent Roman era buildings into Vandal citadels. Although this devastation was significant, the Vandal era saw restoration of much of the damage, an expansion in the size of the population, and the creation of a vibrant Romanized Germanic community.

The city's port meanwhile served as a base for some of the Vandal fleet which continued to reign supreme in the western seas. In turn, the city saw its economic fortunes revive as Vandal merchants cornered the market on shipping. However, much of this wealth was of necessity channeled toward military developments, as the Vandals were forced to defend their conquest against both Byzantine and Berber attacks. A vibrant Romanized Germanic community saw an expansion of the population, and the Vandal merchant fleet provided economic fortunes.

After several decades of war with the Eastern Roman Emperor, the Vandal Kingdom of Africa was ground down and the city was captured, with the rest of the Vandal Kingdom, by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I. The Emperor kept the walls strong but tore down the Vandal citadels, restored the Vandal citadels into Roman civil buildings and returned the city to a traditional post of Byzantine civilization, suppressing the Germanic aristocracy..

However, the vibrant Germanic community which had brought new economic development to the area was ruthlessly suppressed. Although the majority of its population was left unscathed, its economic power was ruined and its place as an aristocracy was overthrown with new Byzantine courtiers.

Without the military abilities of the Vandal nobility and classes of Vandal freeholder framers and urban dwellers, by the 8th century, the city and surrounding area lacked a competent defense. The Byzantine elite turned from this stratified system to an increased use of Berber workers. Berbers were allowed to settle in return for cheap labor. Over a period of fifteen years, successive waves of Arab armies into Byzantine North African territory. They lay siege to the city. Despite being resupplied by Byzantine fleets, the population accepted Islamic supremacy in return for protected status.

Romanization and Christianity center

Considered to be one of the more loyal of Roman provincial capitals, Caesarea grew under Roman rule in the 1st and 2nd century AD, soon reaching a population of over 30,000 inhabitants.[3] In 44 AD, dng the reign of Emperor Claudius it became the capital of the imperial province of Mauretania Caesarensis. Later, the emperor made it a colonia, “Colonia Claudia Caesarea”. As with many other cities throughout the empire, he and his successors further Romanised the area, building monuments, enlarging the bath houses, adding an amphitheatre, and improving the aqueducts. Later, under the Severan dynasty, a new forum was added. The city was sacked by Berber tribes during a revolt in 371/372 AD, but recovered.

In later centuries, the Roman population expanded, as did the Berber population, resulting in a mixed Berber and Roman population. The city was mostly Romanized under Septimius Severus and it grew to be a very rich city with nearly 100,000 inhabitants, according to historian Gsell. In about 165 AD, it was the birthplace to the future Roman Emperor Macrinus.

From an early stage, the city had a small but growing population of Christians, Roman and Berber and was noted for the religious debates and tumults which featured the hostility of Roman public religion toward Christians. By the 4th century, the conversion of the population from pagan to Christian beliefs resulted in nearly all of the population being Christianised.

By the 5th century the capital of Mauretania Caesariensis was totally Romanised, according to Theodore Mommsen, one of the 80 cities in the Maghreb populated (and sometimes even created) by Roman colonists from Italy. It remained an extremely loyalist force for the Roman Empire. Additionally, the Romanized city's elite held considerable control of international trade. Although it stagnated for over a hundred years and even lost population, as did most cities in the Roman Empire, it still remained much as it had been since it was founded. Consequently, the Roman Empire largely relied on its North African dominion for essential grain supply and some elite rulers.

It became a target of the Vandals and was finally taken over by them in 429 AD. The Vandal army and fleet burnt the town and turned many of its old magnificent Roman era buildings into Vandal citadels. Although this devastation was significant, the Vandal era saw restoration of much of the damage, an expansion in population, and the creation of a vibrant Romanised Germanic community.

The area and remained in Vandal hands until 533 AD, when the city was captured by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. The new rulers used the Greek language (along with Latin), but the Neo-Latin local dialect remained in use by the inhabitants. The city declined. The Roman and the semi-Romanised Vandal population held a stratified position over the growing numbers of Berbers it allowed to settle in return for cheap labor.[4] This reduced the economic status of small freeholders and urban dwellers, especially what remained of the Vandal population, who provided most of the local military forces. Furthermore, the increasing use of Berber workers ground down the Roman population of free peasants. By the 8th century, the city and surrounding area had neither a strong urban middle class of free citizens, nor a rural population of freehold farmers, nor a crack military aristocracy of Vandal warriors and their retinue. It thus succumbed to an Arab Moslem jihad.

Muslim age

Successive waves of Islamic jihads into Byzantine North African territory over 15 years wore down the smaller and less motivated imperial forces, until finally Moslem tribesmen laid siege to the city of Caesarea and, although the defenders were resupplied by Byzantine fleets, finally overwhelmed it. Much of the Byzantine nobility and officials fled to other parts of the Empire, while most of the remaining Roman and semi-Roman Berber population accepted Islamic rule which granted them protected status.

Some remained Christians, but hope of living as free Christians under Islamic rulers was dashed[5] For two generations what remained of the Roman population and Romanized Berbers launched several revolts often in conjunction with reinforcements from the Empire. In turn, Islamic forces would react with even more death and oppression. After several revolts by Berbers and what remained of the Romano-Berber and tiny partially Vandal populations, Arab Moslems in the ninth century tore down much of the city's defences and recycled its crumbling Roman buildings, leaving the former city little more than a small village and pale relic of its former glory, surrounded by a camp of Moslem warriors and their retinue. Additionally, the various Jihads and growing numbers of Arab tribesmen forcibly converted the majority of the population to Islam over two centuries of oppression and war. As a result, most of what remained of Roman and Vandal civilization, including the language and Christianity disappeared under the onslaughts of Arab attacks.

Nonetheless, after the tenth century later Berbero-Islamic rule was more tolerant and respectful of the Greco-Roman Christian past and endeavored to rebuild aspects of the town's former civilization. For the following few centuries, the city remained a power center of Arabs and Berbers with a small but significant population of semi-Roman Christians who were fully assimilated by the beginning of the early Renaissance.

The inhabitants became increasingly Arabised. By the 10th century, the city's name had transformed in the local dialect from a Latin to a Berber and ultimately into the Arabised form Sharshal (in French orthography, Cherchell).

Post-Roman history

For two generations, what remained of the quasi-Roman population and Berbers launched several revolts often in conjunction with reinforcements from the Empire. Islamic forces duly crushed these revolts. After several revolts by Berbers and what remained of the Roman and tiny Vandal populations, Arab Moslems tore down much of the city's defenses and recycled its crumbling Roman buildings. The city, already little more than a relic of its former glory, was now surrounded by a camp of Moslem warriors and their retinue. Additionally, joined by growing numbers of Arab tribesmen, most of the town was converted forcibly or otherwise over the following two centuries. By the 10th century, the city's name had transformed in the local dialect from a Latin to a Berber and ultimately into the Arabicized name of for Caesarea, Sharshal.

Nonetheless, later Berbo-Islamic rule was more tolerant and respectful of its Greco-Roman Christian past and endeavored to rebuild aspects of the towns former civilization. For the following few centuries, the city remained a power center of Arabs and Berbers with a small but significant population of semi-Roman Christians. During this period, several attempts at reconquest were made by Europeans, who under various nationalities such as Spanish, French, or Norman managed to hold the city off and on for a few generations before being pushed out again by Moslems. Notable of these in providing material for historical review, especially of what remained of its Roman and Byzantine infrastructure and population was the Norman Kingdom of Africa.

Eventually, Ottoman Turks managed to successfully reconquer the city from Spanish occupation in the 16th century, using the city primarily as a fortified port. In 1520, Hayreddin Barbarossa captured the town and annexed the Algerian Pashalic. His elder brother Oruç Reis built a fort over the town. Under Turkish occupation, the city's importance as a port and fort led to it being inhabited by Moslems of many nationalities, some engaging in privateering and piracy on the Mediterranean.

In reply, European navies and especially the French Navy and the Knights Hospitaller (self-proclaimed descendants of the Crusaders) laid siege to the city and occasionally captured it for limited periods of time. For a century in the 1600s and for a brief period in the 1700s the city either was under Spanish or Hospitallar control. During this period a number of palaces were built, but the overwhelming edifice of Hayreddin Barbarossa's citadel, was considered too militarily valuable to destroy and uncover the previous ancient buildings of old Caesarea.

In 1738, a terrible earthquake shook the town and left the town defenses damaged.

French control

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars and Revolutions of the early 19th century, the French under both British, American, and other European powers were encouraged to attack and destroy the Barbary Pirates. From 1836 to 1840 various allied navies, but mostly French hunted down the Barbary pirates and conquered the Barbary ports while threatening the Ottoman Empire with war if it intervened. In 1840, the French after a significant siege captured and occupied the town. The French lynched the Barbary Pirates including the local pasha for Crimes against the laws of nations.{fact}

.png)

In turn, many ancient statues and buildings were either restored and left in Cherchell, or taken to museums in Algiers, Algeria or Paris, France for further study. However, not all building projects were successful in uncovering and restoring the ancient town. The Roman amphitheatre was considered mostly unsalvageable and unnecessary to rebuilt. Its dress stones were used to the build a new French fort and barracks. Materials from the Hippodrome were used to build a new church. The steps of the Hippodrome were partly destroyed by Cardinal Charles Lavigerie in a search for the tomb of Saint Marciana.

French occupation also brought new European settlement, to join the city's long-established communities of semi-Arabized Christians of local origin and old European merchant families, in addition to Berbers and Arab Muslims. Under French rule, European and Christians became a majority of the population again until World War II.

In the immediate years before World War Two, losses to the French national population from World War One, and a declining birthrate in general among Europeans kept further colonial settlement to a trickle. Arab and Berber populations started seeing an increase in growth. French-Algerian colonial officials and landowners encouraged larger numbers of surrounding Berber tribesmen to move into the surrounding region to work the farms and groves cheaply. In turn, more and more Berbers and Arabs moved into the city seeking employment. By 1930 the combined Berbo-Arab Algerian population represented nearly 40% of the city's population.

The changing demographics within the city were disguised by the large numbers of French military personnel based there and the numbers of European tourists visiting the what had become known as the Algerian Riviera. Additionally, during World War II, Cherchell, with its libraries, cafes, restaurants, and hotels served as a base for the United States Army and Allied War effort, hosting a summit conference between the US and UK in October 1942.

The end of the war with its departure of Allied forces and a reduction of French naval personnel due to rebasing saw an actual decline in Europeans living in the city. Additionally, the general austerity of the post-war years dried up the tourism industry and caused financial stagnation and losses to the local Franco-Algerian community. In 1952, a census recorded that the Frenco-Algerian population had declined to 50% of the popupation.

For the remaining 1950's Cherchell was only slightly caught up by the Algerian War of Independence. With its large proportion of Europeans, French control and influence was strong enough to discourage all but the most daring attacks by anti-French insurgents. By 1966, after independence from the French, Cherchell had lost nearly half of its population and all of its Franco-Algerian population.

Independent Algeria

Cherchell has continued to grow post-independence, recovering to peak colonial-era population by the 1980s. Cherchell currently has industries in marble, plaster quarries and iron mines. The town trades in oils, tobacco and earthenware. Additionally, the ancient cistern first developed by Juba and Cleopatra Selene II was restored and expanded under recent French rule and still supplies water to the town.

Although the Algerian Riveria ended with the war, Cherchell is still a popular tourist places in Algeria. Cherchell has various splendid temples and monuments from the Punic, Numidian and Roman periods, and the works of art found there, including statues of Neptune and Venus, are now in the Museum of Antiquities in Algiers. The former Roman port is no longer in commercial use and has been partly filled by alluvial deposits and has been affected by earthquakes. The former local mosque of the Hundred Columns contains 89 columns of diorite. This remarkable building now serves as a hospital. The local museum displays some of the finest ancient Greek and Roman antiquities found in Africa. Cherchell is the birthplace of writer and movie director Assia Djebar.

Historical population

| Year | Population[1] |

|---|---|

| 1901 | 9,000 |

| 1926 | 11,900 |

| 1931 | 12,700 |

| 1936 | 12,700 |

| 1954 | 16,900 |

| 1966 | 11,700 |

| 1987 | 18,700 |

| 1998 | 24,400 |

| 2015 | 30,000 |

Ecclesiastical history

Apart from some bishops who may have been of the church in Caesarea and whose names are engraved in inscriptions that have been unearthed, the first bishop whose name is preserved in extant written documents is Fortunatus, who took part in the Council of Arles of 314, which condemned Donatism as heresy. A letter of Symmachus mentions a bishop named Clemens in about 371/372 or 380. The town became a Donatist centre and at the joint Conference of Carthage in 411, was represented both by the Donatist Emeritus and by the Catholic Deuterius. Augustine of Hippo has left an account of his public confrontation with Emeritus at Caesarea in the autmn of 418, after which Emeritus was exiled. The last bishop of Caesarea whose name is known from written documents was Apocorius, one of Catholic bishops whom Huneric summoned to Carthage in 484 and then sent into exile. An early 8th-century Notitia Episcopatuum still included this see.[6][7]

Titular see

No longer a residential bishopric, Caesarea in Mauretania is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[8]

The diocese was nominally restored as a titular bishopric under the name Caesarea in the 19th century, which was specified as Caesarea in Mauretania in 1933.

It has had many incumbents, both of the lowest (episcopal) and intermediary (archiepiscopal) ranks :

- Titular Bishop Biagio Pisani (1897.04.23 – 1901.06.07) (later Archbishop)

- Titular Bishop Pietro Maffi (1902.06.09 – 1903.06.22) (later Cardinal)

- Titular Bishop Thomas Francis Brennan (1905.10.07 – 1916.03.20)

- Titular Archbishop Pierre-Célestin Cézerac (1918.01.02 – 1918.03.18)

- Titular Archbishop Cardinal Wilhelmus Marinus van Rossum, Redemptorists (C.SS.R.) (1918.04.25 – 1918.05.20)

- Titular Archbishop Benedetto Aloisi Masella (1919.12.15 – 1946.02.18) (later Cardinal)

- Titular Bishop Luigi Cammarata (1946.12.04 – 1950.02.25)

- Titular Bishop Francesco Pennisi (1950.07.11 – 1955.10.01)

- Titular Bishop André-Jacques Fougerat (1956.07.16 – 1957.01.05)

- Titular Bishop Carmelo Canzonieri (1957.03.11 – 1963.07.30)

- Titular Bishop: Archbishop Enea Selis (1964.01.18 – 1971.09.02)

- Titular Bishop Giuseppe Moizo (1972.01.22 – 1976.07.01)

- Titular Archbishop Sergio Sebastiani (1976.09.27 – 2001.02.21) (later Cardinal)

- Titular Bishop Gerard Johannes Nicolaas de Korte (2001.04.11 – 2008.06.18)

- Titular Bishop Stanislaus Tobias Magombo (2009.04.29 – 2010.07.06)

- Titular Archbishop Walter Brandmüller (2010.11.04 – 2010.11.20) (later Cardinal)

- Titular Archbishop (2011.11.26 – ...): Marek Solczyński Apostolic Nuncio (papal ambassador) to Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia (2011.11.26 – ...).

Remains

Earthquakes, wars and plunder have ravaged many of the ancient remains.

The town (of Caesarea) remains insufficiently known....The town walls, studied in 1946, pose more problems; and the monuments are more often simply marked than completely known. The amphitheater, which has been excavated, remains unpublished; the very large hippodrome, which appears clearly on aerial photographs, is known only through old borings. The temples, which have been found on a spur of the mountain to the East of the central esplanade, on the edge of the route from Ténès to the West of the modern town, are too much destroyed to warrant publication even of plans. The baths along the edge of the sea, rather majestic, are also badly preserved. One would scarcely recognize several houses recently excavated. Grouped around peristyles with vast trichinia, they are readily adapted to the terrain and are constructed on terraces on the lower slopes or on the edge of cliffs with views over the sea. They often are preserved for us only in a late form—4th c. A.D.—and traces of the era of Juba are found only in the lower strata. The theater is an exception; still well preserved in 1840, it has since served as a quarry. It was set against the slope of the mountain. At the back of the scaena towards the N was a portico, covered over today by a street, where Gsell saw the S side of the forum. Of the rich scaenae frons there remain only traces and several statues, of which two are colossal muses. The orchestra had hater undergone great modification which had resulted in the disappearance of the platform of the stage: an oval arena had been built, intended for hunting spectacles, and a wall was raised between the first row of seats and the cavea to protect spectators from the wild beasts. The sumptuously decorated monument is consequently very much mutilated, but is of interest specifically because of its complex history.The amphitheater, in the E part of the town, was erected in flat open country. It was not oval but rectangular, with the short sides rounded. The tiers of seats, for the most part missing, were carried on ramping vaults, and the arena floor was cut by two perpendicular passages intended for beasts. It is in this arena that St. Marciana was martyred.[9]

Some remains can be seen in the local Archeological Museum of Chercell-Caesarea.

Gallery

- Roman amphiteater

Section of Caesarea's Roman aqueduct

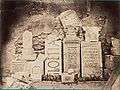

Section of Caesarea's Roman aqueduct Photography of ancient Roman inscriptions from Cherchell, 1856

Photography of ancient Roman inscriptions from Cherchell, 1856 Photography of Roman remains from Caesarea, 1856

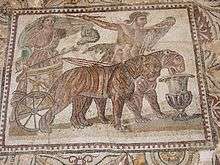

Photography of Roman remains from Caesarea, 1856- Mosaic "Les tres Graces" (the 3 beauties) from Caesarea

Portrait of Juba II, found in Caesarea

Portrait of Juba II, found in Caesarea Mosaic of vineyard workers

Mosaic of vineyard workers Mosaic of the leopards

Mosaic of the leopards

See also

References

- 1 2 "populstat.info". populstat.info. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Leveau Philipe: "L'amphithéâtre et le théâtre-amphithéâtre de Cherchel" (in French)

- ↑ Leveau, Philippe. "Caesarea de Maurétanie, une ville romaine et ses campagnes" first chapter

- ↑ Leveau, Philippe. "Caesarea de Maurétanie, une ville romaine et ses campagnes" third chapter

- ↑ Virginie Prevost. "Prevost: Les dernières communautés chrétiennes autochtones d’Afrique du Nord" ()

- ↑ Joseph Mesnage, L'Afrique chrétienne, Paris 1912, pp. 447–450

- ↑ Charles Courtois, v. Césarée de Maurétanie, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 203-206

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 867

- ↑ Princeton: Iol

- 2002 Microsoft Encarta Encyclopaedia.

- Children's Britannica - Volume 1, Abbey to Arabs, Algeria

- S. Pétridès (1908). "Caesarea Mauretaniae". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- "Cherchell". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911.

Sources and External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cherchell. |

- GigaCatholic with titular incumbent biography links

- Various ancient ruins of Cherchell:

%2C_Algeria_04966r.jpg)