Children of a Lesser God

| Children of a Lesser God | |

|---|---|

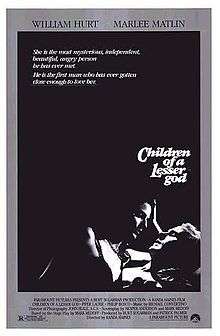

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Randa Haines |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Children of a Lesser God by Mark Medoff |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Michael Convertino |

| Cinematography | John Seale |

| Edited by | Lisa Fruchtman |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

| Budget | $2 million[1] |

| Box office | $31,853,080 (North America) |

Children of a Lesser God is a 1986 American romantic drama film directed by Randa Haines and written by Hesper Anderson and Mark Medoff. An adaptation of Medoff's Tony Award–winning stage play of the same name, the film stars Marlee Matlin (in an Oscar-winning performance) and William Hurt as employees at a school for the deaf: a deaf custodian and a hearing speech teacher, whose conflicting ideologies on speech and deafness create tension and discord in their developing romantic relationship.

Marking the film debut for deaf actress Matlin, Children of a Lesser God is notable for being the first since the 1926 silent film You'd Be Surprised to feature a deaf actor in a major role.[2]

After meeting deaf actress Phyllis Frelich in 1977 at the University of Rhode Island's New Repertory Project, playwright Medoff wrote the play Children of a Lesser God to be her star vehicle.[3] Based partially on Frelich's relationship with her hearing husband Robert Steinberg,[4] the play chronicles the turmoiled relationship and marriage between a reluctant-to-speak deaf woman and an unconventional speech pathologist for the deaf. With Frelich starring, Children of a Lesser God opened on Broadway in 1980, received three Tony Awards, including Best Play, and ran for 887 performances before closing in 1982.[5]

Enjoying the vast success of his Broadway debut, Medoff, with fellow writer Anderson, penned a screenplay adapted from the original script. Though many changes were made, the core love story remained intact. The film version premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 13, 1986 and was released widely in the United States on October 3 of the same year. Like its source material, the film generally gained praise from the hearing and deaf communities alike.

It received five Academy Award nominations, including Matlin's win for Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role.[6] Only 21 years old at the time, Matlin is the youngest actress to receive the award in this particular category and the only deaf Academy Award recipient in any category.[7]

Plot

Sarah Norman (Marlee Matlin) is a troubled young deaf woman working as a janitor at a school for the deaf and hard of hearing in New England. An energetic new teacher, James Leeds (William Hurt), arrives at the school and encourages her to set aside her insular life by learning how to speak aloud.

As she already uses sign language, Sarah resists James's attempts to get her to talk but she is resistant because of a history of rape. Romantic interest develops between James and Sarah and they are soon living together, though their differences and mutual stubbornness eventually strains their relationship to the breaking point, as he continues to want her to talk, and she feels somewhat stifled in his presence.

Sarah leaves James and goes to live with her estranged mother (Piper Laurie) in a nearby city, reconciling with her in the process. However, she and James later find a way to resolve their differences.

Title

The title of the film comes from the twelfth chapter of Alfred Lord Tennyson's Idylls of the King. The stanza in which the line is contained reads as follows:

I found Him in the shining of the stars,

I marked Him in the flowering of His fields,

But in His ways with men I find Him not.

I waged His wars, and now I pass and die.

O me! for why is all around us here

As if some lesser god had made the world,

But had not force to shape it as he would,

Till the High God behold it from beyond,

And enter it, and make it beautiful?

Or else as if the world were wholly fair,

But that these eyes of men are dense and dim,

And have not power to see it as it is:

Perchance, because we see not to the close;—

For I, being simple, thought to work His will,

And have but stricken with the sword in vain;

And all whereon I leaned in wife and friend

Is traitor to my peace, and all my realm

Reels back into the beast, and is no more.

My God, thou hast forgotten me in my death;

Nay—God my Christ—I pass but shall not die.[1][2]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Sherrod-tcmwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Tennysonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Production

The movie was shot primarily in and around Saint John, New Brunswick, with the Rothesay Netherwood School serving as the main set. Aside from locations in Saint John and Rothesay Netherwood School, sets were constructed by Saint John local Keith MacDonald.

Cast

- Marlee Matlin as Sarah Norman

- William Hurt as James Leeds

- Piper Laurie as Mrs. Norman

- Philip Bosco as Dr. Curtis Franklin

- Allison Gompf as Lydia

- Bob Hiltermann as Orin

- Linda Bove as Marian Loesser

Box office

Although budget details are not known, the film opened at number 5 at the North American box office with an opening weekend gross of $1,909,084. The film stayed in the Top 10 for eight weeks and grossed a total of $31,853,080 in North America.[8]

Reaction

Critical reception

Children of a Lesser God received generally positive reviews. On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film received a score of 81%.[9] Particular praise was given to the film's two leads. Richard Schickel of TIME Magazine said of Matlin, "she has an unusual talent for concentrating her emotions--and an audience's--in her signing. But there is something more here, an ironic intelligence, a fierce but not distancing wit, that the movies, with their famous ability to photograph thought, discover in very few performances."[10] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 3 out of a possible 4 stars, describing the subject matter as "new and challenging", saying he was "interested in everything the movie had to tell me about deafness." He continued, "The performances are strong and wonderful - not only by Hurt, one of the best actors of his generation, but also by Matlin, a deaf actress who is appearing in her first movie. She holds her own against the powerhouse she's acting with, carrying scenes with a passion and almost painful fear of being rejected and hurt, which is really what her rebellion is about."[11] Paul Attasanio of the Washington Post said of the film, "This is romance the way Hollywood used to make it, with both conflict and tenderness, at times capturing the texture of the day-to-day, at times finding the lyrical moments when two lovers find that time stops." He goes on to say of Matlin, "The most obvious challenge of the role is to communicate without speaking, but Matlin rises to it in the same way the stars of the silent era did -- she acts with her eyes, her gestures."[12]

There was some criticism that the film was told entirely from a hearing perspective, for a hearing audience. The film is not subtitled (neither the spoken dialogue nor the signing); instead, as pointed out by Ebert, the signed dialogue is repeated aloud by Hurt's character, "as if to himself".[11]

Hurt, Matlin, and Piper Laurie (in her role as Sarah's mother, Mrs. Norman) all went on to receive Academy Award nominations for their performances. Only Matlin won, becoming the first and only deaf performer to win to date, as well as the youngest winner in the Lead Actress category.

Awards

- Academy Award (1987): Best Actress in a Leading Role – Marlee Matlin

- Golden Globe (1987): Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama – Marlee Matlin

- Berlin International Film Festival (1987): Silver Bear – Randa Haines[13]

- Berlin International Film Festival (1987): Reader Jury of the "Berliner Morgenpost" – Randa Haines

References

- ↑ Box Office Information for Children of a Lesser God. The Wrap. Retrieved April 4, 2013

- ↑ Schuchman, John S. (1999). Hollywood Speaks: Deafness and the Film Entertainment Industry. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-252-06850-8.

- ↑ Medoff, Mark (1981). Children of a Lesser God. Clifton, NJ: James T. White & Company. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-88371-032-6.

- ↑ Lang, Harry G.; Meath-Lang, Bonnie (1995). Deaf Persons in the Arts and Sciences: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-313-29170-8.

- ↑ "Children of a Lesser God". Internet Broadway Database. The League of American Theatres and Producers. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Results Page – Academy Awards Database – AMPAS". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Help Page – Academy Awards Database – AMPAS". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Children of a Lesser God". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- ↑ "Children of a Lesser God". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard (June 21, 2005). "Miracle Worker: CHILDREN OF A LESSER GOD". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2012-12-27. Subscription required.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (October 3, 1986). "Children Of A Lesser God". Chicago Sun Times. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ Attasanio, Paul (October 3, 1986). "'Children of a Lesser God'". Washington Post. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ "Berlinale: 1987 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- Sherrod, Kerryn. "Children Of A Lesser God". Turner Classic Movies Database. Turner Classic Movies.

- Tennyson, Alfred Lord. "Idylls of the King". eBooks.Adelaide.edu.au. University of Adelaide, South Australia.