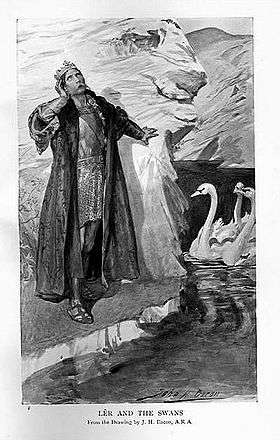

Children of Lir

The Children of Lir[1] is an Irish legend. The original Irish title is Clann Lir or Leanaí Lir, but Lir is the genitive case of Lear. Lir is more often used as the name of the character in English. The legend is part of the Irish Mythological Cycle, which consists of numerous prose tales and poems found in medieval manuscripts.

| “ | Out with you upon the wild waves, Children of the King!

Henceforth your cries shall be with the flocks of birds. |

” |

Summary

Bodb Derg was elected king of the Tuatha Dé Danann, much to the annoyance of Lir. To appease Lir, Bodb gave one of his daughters, Aoibh, to him in marriage. Aoibh bore Lir four children: one girl, Fionnuala, and three sons, Aodh and twins, Fiachra and Conn.

Aoibh died, and her children missed her terribly. Wanting to keep Lir happy, Bodb sent another of his daughters, Aoife, to marry Lir.

Jealous of the children's love for each other and for their father, Aoife plotted to get rid of the children. On a journey with the children to Bodb's house, she ordered her servant to kill them, but the servant refused. In anger, she tried to kill them herself, but did not have the courage. Instead, she used her magic to turn the children into swans. When Bodb heard of this, he transformed Aoife into an air demon for eternity.

As swans, the children had to spend 300 years on Lough Derravaragh (a lake near their father's castle), 300 years in the Sea of Moyle, and 300 years on the waters of Irrus Domnann[2][3] Erris near to Inishglora Island (Inis Gluaire).[4] To end the spell, they would have to be blessed by a monk. While the children were swans, Saint Patrick converted Ireland to Christianity.

Endings

After the children, as swans, spent their long periods in each region, they received sanctuary from MacCaomhog (or Mochua), a monk in Inis Gluaire.

Some versions of the tale claim each child was tied to the other with silver chains to ensure that they would stay together forever. However Deoch, the wife of the King of Leinster and daughter of the King of Munster, wanted the swans for her own, so she ordered her husband Lairgean to attack the monastery and seize the swans. In this attack, the silver chains were broken and the swans transformed into old, withered people.

Another version of the legend tells that as the king was leaving the sanctuary with the swans, the bell of the church tolled, releasing them from the spell. Before they died, each was baptised and then later buried in one grave, standing, with Fionnuala, the daughter, in the middle, Fiacre and Conn, the twins, on either side of her, and Aodh in front of her.

In an alternative ending, the four suffered on the three lakes for 900 years, and then heard the bell. When they came back to the land a priest found them. The swans asked the priest to turn them back into humans, and he did, but since they were over 900 years old, they died and lived happily in heaven with their mother and father.

Cultural references

- The song Silent O Moyle, Be The Roar of Thy Water (the song of Fionnuala) from Thomas Moore's Irish Melodies, tells the story of the children of Lir.

- Irish composer Geoffrey Molyneux Palmer (1882–1957) based his opera Srúth na Maoile (1923) on the legend of the children of Lir.

- Irish composer Hamilton Harty (1879–1941) wrote the orchestral tone poem The Children of Lir (1938).

- Irish composer Patrick Cassidy (born 1956) wrote The Children of Lir (1991), an oratorio with libretto in the Irish language.[5]

- The story is retold within Gods and Fighting Men[6] by Irish folklorist Lady Augusta Gregory, first published in 1904.

- The story is also told within Irish Sagas and Folktales by folklorist Eileen O'Faolain and first published by Oxford University Press in 1954.

- It has been suggested that the site of Lir's castle is currently occupied by Tullynally Castle, home of the Earl of Longford, as the name "Tullynally" is the anglicised form of Tullach na n-eala or "hill of the swan".

- A statue of the Children of Lir, created by the sculptor Oisin Kelly and cast by Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry of Florence, Italy, is in the Garden of Remembrance, Parnell Square in Dublin, Ireland. It symbolises the rebirth of the Irish nation following 900 years of struggle for independence from England and, later, the United Kingdom, much as the swans were "reborn" following 900 years.

- Another statue depicting the legend is located in the central triangular green of the village of Castlepollard, some three-miles northeast of Lough Derravaragh. A plaque outlines the famous story in several languages.

In popular culture

- T.H. White references the Children of Lir in the King Arthur saga, The Once and Future King.

- There is a Russian Celtic-folk band named Clann Lir, that is led by Russian vocalist and harpist Natalia O'Shea.

- Folk-rock group Loudest Whisper recorded an album The Children of Lir based on a stage presentation of the legend in 1973–74.

- Folk metal-band Cruachan published a song called "Children of Lir" on their album Folk-Lore in 2002.

- Pagan-metal group Primordial wrote a song called "Children of the Harvest" based on the legend.

- Lir's children are referred to by Irish singer Sinéad O'Connor in "A Perfect Indian".

- "Children of Lir" is a song depicting the legend sung by Sora in her album Heartwood.

- Irish stand-up comedian Tommy Tiernan gave a manic and almost nonsensical version of the story, making statements like "The daddy come home and say 'Where my beautiful children?' 'Don't be talkin' to me, I turned 'em into 'wans'" in his comedy special "Crooked Man" while lampooning traditional Irish storytelling.

- Mary McLaughlin has an album "Daughter of Lír" on which there are two songs dealing with this legend, "Fionnuala's Song" and "The Children of Lir"

- Walter Hackett has written a modern retelling of the tale of the Children of Lir in "The Swans of Ballycastle," illustrated by Bettina, published by Ariel Books, Farrar, Straus & Young Inc., New York, 1954.

References

- ↑ "The Fate of the Children of Lir". Ancienttexts.org. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ↑ Séamas Pender (1933). "The Fir Domnann". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 3 (1): 101–115. JSTOR 25513670.

- ↑ The fate of the Children of Lir. Mythicalireland.com (16 March 2000). Retrieved on 21 November 2010.

- ↑ Inishglora. Irishislands.info. Retrieved on 21 November 2010.

- ↑ http://www.patrickcassidy.com/discography/

- ↑ Gregory, Augusta (1905). "Gods And Fighting Men". The Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Category:Ireland in fiction