Chinese musical notation

Systems of musical notation have been in use in China for over two thousand years. Different systems have been used to record music for bells and for the guqin stringed instrument. More recently a system of numbered notes (jianpu) has been used, with resemblances to Western notations.

Ancient

The earliest known examples of text referring to music in China are inscriptions on musical instruments found in the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (d. 433 B.C.). Sets of 41 chimestones and 65 bells bore lengthy inscriptions concerning pitches, scales, and transposition. The bells still sound the pitches that their inscriptions refer to. Although no notated musical compositions were found, the inscriptions indicate that the system was sufficiently advanced to allow for musical notation. Two systems of pitch nomenclature existed, one for relative pitch and one for absolute pitch. For relative pitch, a solmization system was used.[1]

Guqin notations

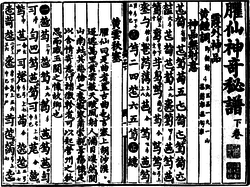

The tablature of the guqin is unique and complex. The older form is composed of written words describing how to play a melody step-by-step using the plain language of the time, i.e. descriptive notation (Classical Chinese).

The newer form of guqin notation is composed of bits of Chinese characters put together to indicate the method of play is called prescriptive notation. Rhythm is only vaguely indicated in terms of phrasing. Tablatures for the qin are collected in what is called qinpu.

Gongche notation

Gongche notation, dating from the Tang dynasty, used Chinese characters for the names of the scale.

Jianpu (numbered musical notation)

The jianpu system of notation (probably an adaptation of a French Galin-Paris-Cheve system) had gained widespread acceptance by 1900. It uses a movable do system, with the scale degrees 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 standing for do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si. Dots above or below a numeral indicate the octave of the note it represents. Key signatures, barlines, and time signatures are also employed. Many symbols from Western standard notation, such as bar lines, time signatures, accidentals, tie and slur, and the expression markings are also used. The number of dashes following a numeral represents the number of crotchets (quarter notes) by which the note extends.

References

- ↑ Bagley, Robert (2004). "The Prehistory of Chinese Music Theory" (Elsley Zeitlyn Lecture on Chinese Archaeology and Culture), Britac.ac.uk.