Cholera vaccine

| |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Cholera |

| Type | Killed/Inactivated |

| Clinical data | |

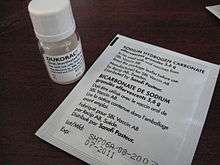

| Trade names | Dukoral, other |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| ATC code | J07AE01 (WHO) J07AE02 (WHO) |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider | none |

| | |

Cholera vaccines are vaccines that are effective at preventing cholera.[1] They are about 85% effective during the first six months and 50–60% effective during the first year.[1][2][3] The effectiveness decreases to less than 50% after two years. When a significant portion of the population is immunized benefits from herd immunity may occur among those not immunized. The World Health Organization recommends their use in combination with other measures among those at high risk. Two doses or three doses of the oral form are typically recommended.[1] An injectable form is available in some, but not all, areas of the world.[1][2]

Both of the available types of oral vaccine are generally safe. Mild abdominal pain or diarrhea may occur. They are safe in pregnancy and in those with poor immune function. They are licensed for use in more than 60 countries. In countries where the disease is common, the vaccine appears to be cost effective.[1]

The first vaccines used against cholera were developed in the late 1800s. They were the first widely used vaccine that was made in a laboratory.[4] Oral vaccines were first introduced in the 1990s.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[5] The cost to immunize against cholera is between 0.1 and 4.0 USD.[6]

Medical use

Oral cholera vaccines are increasingly used as an additional tool to control cholera outbreaks in combination with the traditional interventions to improve safe water supply, sanitation, handwashing and other means to improve hygiene. Since licensure of Dukoral and Shanchol, over a million doses of these vaccines have been deployed in various mass oral cholera campaigns around the world.[7] In addition, Vietnam incorporates oral cholera vaccination in its public health programme and over 9 million doses have been administered through targeted mass vaccination or immunization of school-aged children in cholera endemic regions.

The cholera vaccine is largely used by backpackers and persons visiting locations where there is a high risk of cholera infection. However, since it does not provide 100% immunity from the disease, food hygiene precautions should also be taken into consideration when visiting an area where there is a high risk of becoming infected with cholera. Although the protection observed has been described as "moderate", herd immunity can multiply the effectiveness of vaccination. Dukoral has been licensed for children 2 years of age and older, Shanchol for children 1 year of age and older. The administration of the vaccine to adults confers additional indirect protection (herd immunity) to children.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends both preventive and reactive use of the vaccine, making the following key statements:[8]

WHO recommends that current available cholera vaccines be used as complements to traditional control and preventive measures in areas where the disease is endemic and should be considered in areas at risk for outbreaks. Vaccination should not disrupt the provision of other high priority health interventions to control or prevent cholera outbreaks.... Reactive vaccination might be considered in view of limiting the extent of large prolonged outbreaks, provided the local infrastructure allows it, and an in-depth analysis of past cholera data and identification of a defined target area have been performed.

The WHO as of late 2013 established a revolving stockpile of 2 million OCV doses.[9] The supply is increasing to 6 million as a South Korean companies has gone into production (2016), the old production not being able to handle WHO demand in Haiti and Sudan for 2015, nor prior years. GAVI Alliance donated $115 million to help pay for expansions.[10][11]

Oral

Oral vaccines provide protection in 52% of cases the first year following vaccination and in 62% of cases the second year.[3] There are two variants of the oral vaccine currently in use: WC-rBS and BivWC. WC-rBS (marketed as "Dukoral") is a monovalent inactivated vaccine containing killed whole cells of V. cholerae O1 plus additional recombinant cholera toxin B subunit. BivWC (marketed as "Shanchol" and "mORCVAX") is a bivalent inactivated vaccine containing killed whole cells of V. cholerae O1 and V. cholerae O139. mORCVAX is only available in Vietnam.

Bacterial strains of both Inaba and Ogawa serotypes and of El Tor and Classical biotypes are included in the vaccine. Dukoral is taken orally with bicarbonate buffer, which protects the antigens from the gastric acid. The vaccine acts by inducing antibodies against both the bacterial components and CTB. The antibacterial intestinal antibodies prevent the bacteria from attaching to the intestinal wall, thereby impeding colonisation of V. cholerae O1. The anti-toxin intestinal antibodies prevent the cholera toxin from binding to the intestinal mucosal surface, thereby preventing the toxin-mediated diarrhoeal symptoms.[12]

Injectable

Although rarely in use, the injected cholera vaccines are effective for people living where cholera is common. They offer some degree of protection for up to two years after a single shot, and for three to four years with annual booster. They reduce the risk of death from cholera by 50% in the first year after vaccination.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Cholera vaccines: WHO position paper." (PDF). Weekly epidemiological record. 13 (85): 117–128. Mar 26, 2010. PMID 20349546.

- 1 2 3 Graves PM, Deeks JJ, Demicheli V, Jefferson T (2010). "Vaccines for preventing cholera: killed whole cell or other subunit vaccines (injected)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (8): CD000974. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000974.pub2. PMID 20687062.

- 1 2 Sinclair D, Abba K, Zaman K, Qadri F, Graves PM (2011). "Oral vaccines for preventing cholera". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD008603. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008603.pub2. PMID 21412922.

- ↑ Stanberry, Lawrence R. (2009). Vaccines for biodefense and emerging and neglected diseases (1 ed.). Amsterdam: Academic. p. 870. ISBN 9780080919027.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ Martin, S; Lopez, AL; Bellos, A; Deen, J; Ali, M; Alberti, K; Anh, DD; Costa, A; Grais, RF; Legros, D; Luquero, FJ; Ghai, MB; Perea, W; Sack, DA (1 December 2014). "Post-licensure deployment of oral cholera vaccines: a systematic review.". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 92 (12): 881–93. doi:10.2471/blt.14.139949. PMID 25552772.

- ↑ Harris, JB; LaRocque, RC; Qadri, F; Ryan, ET; Calderwood, SB (Jun 30, 2012). "Cholera.". Lancet. 379 (9835): 2466–76. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60436-x. PMID 22748592.

- ↑ Oral cholera vaccines in mass immunization campaigns: guidance for planning and use (PDF). World Health Organization. 2010. ISBN 9789241500432.

- ↑ "Oral cholera vaccine stockpile". World Health Organization. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ↑ http://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/world-health-organization-doubles-cholera-vaccine-supply-n492796

- ↑ "GAVI Board Approves Support to Expand Oral Cholera Vaccine Stockpile". The Task Force on Global Health. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ↑ "Dukoral Canadian Product Monograph Part III: Consumer Information" (PDF). Retrieved 8 May 2013.