Cinema Paradiso

| Cinema Paradiso | |

|---|---|

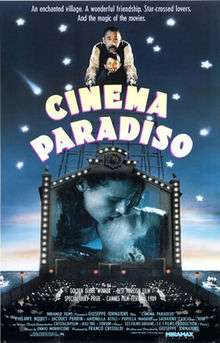

Original release poster | |

| Directed by | Giuseppe Tornatore |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | Giuseppe Tornatore |

| Starring | |

| Music by | |

| Cinematography | Blasco Giurato |

| Edited by | Mario Morra |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

Miramax Films (US) Umbrella Entertainment |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 155 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language |

Italian English Portuguese Sicilian |

| Budget | US$5 million[1] |

| Box office | $12,397,210 (US only)[2] |

Cinema Paradiso (Italian: Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, Italian pronunciation: [ˈnwɔːvo ˈtʃiːnema paraˈdiːzo], "New Paradise Cinema") is a 1988 Italian drama film written and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. The film stars Jacques Perrin, Philippe Noiret, Leopoldo Trieste, Marco Leonardi, Agnese Nano and Salvatore Cascio, and was produced by Franco Cristaldi and Giovanna Romagnoli, while the music score was composed by Ennio Morricone along with his son, Andrea. It won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 62nd Academy Awards.[3]

Plot in original 1988 international release

In Rome, in the 1980s, famous Italian film director Salvatore Di Vita returns home late one evening, where his girlfriend sleepily tells him that his mother called to say someone named Alfredo has died. Salvatore obviously shies from committed relationships and has not been to his home village of Giancaldo, Sicily in 30 years. As his girlfriend asks him who Alfredo is, Salvatore flashes back to his childhood.

It is a few years after World War II. Six-year-old Salvatore is the mischievous, intelligent son of a war widow. Nicknamed Toto, he discovers a love for films and spends every free moment at the movie house Cinema Paradiso. Although they initially start off on tense terms, he develops a friendship with the fatherly projectionist, Alfredo, who takes a shine to the young boy and often lets him watch movies from the projection booth. During the shows, the audience can be heard booing when there are missing sections, causing the films to suddenly jump, bypassing a critical romantic kiss or embrace. The local priest had ordered these sections censored, and the deleted scenes are piled on the projection room floor. At first, Alfredo considers Toto a bit of a pest, but eventually he teaches Salvatore to operate the film projector.

The montage ends as the movie house catches fire (highly flammable nitrate film was in routine use at the time) as Alfredo was projecting The Firemen of Viggiù after hours, on the wall of a nearby house. Salvatore saves Alfredo's life, but not before some film reels explode in Alfredo's face, leaving him permanently blind. The Cinema Paradiso is rebuilt by a town citizen, Ciccio, who invests his football lottery winnings. Salvatore, still a child, is hired as the new projectionist, as he is the only person who knows how to run the machines.

About a decade later, Salvatore, now in high school, is still operating the projector at the Cinema Paradiso. His relationship with the blind Alfredo has strengthened, and Salvatore often looks to him for help — advice that Alfredo often dispenses by quoting classic films. Salvatore has been experimenting with film, using a home movie camera, and he has met, and captured on film, Elena, daughter of a wealthy banker. Salvatore woos — and wins — Elena's heart, only to lose her due to her father's disapproval.

As Elena and her family move away, Salvatore leaves town for compulsory military service. His attempts to write to Elena are fruitless; his letters are returned as undeliverable. Upon his return from the military, Alfredo urges Salvatore to leave Giancaldo permanently, counseling that the town is too small for Salvatore to ever find his dreams. Moreover, the old man tells him, once Salvatore leaves, he must pursue his destiny wholeheartedly, never looking back and never returning, even to visit; he must never give in to nostalgia or even write or think about them. They tearfully embrace, and Salvatore leaves town to pursue his future, as a filmmaker.

Salvatore has obeyed Alfredo, but he returns home to attend the funeral. Though the town has changed greatly, he now understands why Alfredo thought it was important that he leave. Alfredo's widow tells him that the old man followed Salvatore's successes with pride, and he left him something — an unlabeled film reel and the old stool that Salvatore once stood on to operate the projector. Salvatore learns that Cinema Paradiso is to be demolished to make way for a parking lot. At the funeral, he recognizes the faces of many people who attended the cinema when he was the projectionist.

Salvatore returns to Rome. He watches Alfredo's reel and discovers that it comprises a very special montage. It contains all of the romantic scenes the priest had ordered cut from movies; Alfredo had spliced the sequences together to form a single film. Salvatore has made peace with his past.

Cast

- Philippe Noiret as Alfredo

- Salvatore Cascio as Salvatore Di Vita (child)

- Marco Leonardi as Salvatore Di Vita (adolescent)

- Jacques Perrin as Salvatore Di Vita (adult)

- Antonella Attili as Maria (young)

- Enzo Cannavale as Spaccafico

- Isa Danieli as Anna

- Pupella Maggio as Maria (old)

- Agnese Nano as Elena Mendola (adolescent)

- Leopoldo Trieste as Father Adelfio

- Nino Terzo as Peppino's Father

- Giovanni Giancono as The Mayor

- Brigitte Fossey (Extended cut) as Elena Mendola (adult)

Production

Cinema Paradiso was shot in director Tornatore's hometown Bagheria, Sicily, as well as Cefalù on the Tyrrhenian Sea.[4] The famous town square is Piazza Umberto I in the village of Palazzo Adriano, about 30 miles to the south of Palermo. The ‘Paradiso’ cinema was built here, at Via Nino Bixio, overlooking the octagonal Baroque fountain, which dates from 1608.[5] Told largely in flashback of a successful film director Salvatore to his childhood years, it also tells the story of the return to his native Sicilian village for the funeral of his old friend Alfredo, the projectionist at the local "Cinema Paradiso". Ultimately, Alfredo serves as a wise father figure to his young friend who only wishes to see him succeed, even if it means breaking his heart in the process.

Seen as an example of "nostalgic postmodernism",[6] the film intertwines sentimentality with comedy, and nostalgia with pragmaticism. It explores issues of youth, coming of age, and reflections (in adulthood) about the past. The imagery in the scenes can be said to reflect Salvatore's idealised memories of his childhood. Cinema Paradiso is also a celebration of films; as a projectionist, young Salvatore (a.k.a. Totò) develops a passion for films that shapes his life path in adulthood.

Releases

The film exists in multiple versions. It was originally released in Italy at 155 minutes, but poor box office performance in its native country led to its being shortened to 123 minutes for international release; it was an instant success.[7] This international version won the Special Jury Prize at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival[8] and the 1989 Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. In 2002, the director's cut 173-minute version was released (known in the U.S. as Cinema Paradiso: The New Version).

Plot additions in the 2002 director's cut

In the 173-minute version of the film, after the funeral, Salvatore glimpses an adolescent girl who resembles the teenage Elena. He follows the teen as she rides her scooter to her home, which allows Salvatore to contact his long-lost love Elena, who is revealed to be the girl's mother. Salvatore calls her in hopes of rekindling their romance; she initially rejects him, but later reconsiders and goes to see Salvatore, who was contemplating his rejection at a favorite location from their early years. Their meeting ultimately leads to a lovemaking session in her car. He learns that she had married an acquaintance from his school years, who became a local politician of modest means. Afterwards, feeling cheated, he strives to rekindle their romance, and while she clearly wishes it were possible, she rejects his entreaties, choosing to remain with her family and leave their romance in the past.

During their evening together, a frustrated and angry Salvatore asks Elena why she never contacted him or left word of where her family was moving to. He learns that the reason they lost touch was because Alfredo asked her not to see him again, fearing that Salvatore's romantic fulfillment would only destroy what Alfredo sees as Salvatore's destiny – to be successful in film. Alfredo tried to convince her that if she loved Salvatore, she should leave him for his own good. Elena explains to Salvatore that, against Alfredo's instruction, she had secretly left a note with an address where she could be reached and a promise of undying love and loyalty. Salvatore reveals that he never knew of her note, and thus lost his true love for more than thirty years. The next morning, Salvatore returns to the decaying Cinema Paradiso and frantically searches through the piles of old film invoices pinned to the wall of the projection booth. There, on the reverse side of one of the dockets, he finds the handwritten note Elena had left thirty years earlier.

The film ends with Salvatore returning to Rome and viewing the film reel that Alfredo left, tears in his eyes.

Home media

A special edition of Cinema Paradiso was released on DVD by Umbrella Entertainment in September 2006. The DVD is compatible with all region codes and includes special features such as the theatrical trailer, the Director's Cut version, scenes from the Director's Cut, the Ennio Morricone soundtrack and a documentary on Giuseppe Tornatore.[9]

An Academy Award edition of Cinema Paradiso was released on DVD by Umbrella Entertainment in February 2009. It is also compatible with all region codes and includes different special features such as Umbrella Entertainment trailers, cast and crew biographies and the Director's filmography.[10]

In July 2011 Umbrella Entertainment released the film on Blu-ray.[11]

Reception

Cinema Paradiso was a critical and box-office success and is regarded by many as a classic. It is particularly renowned for the 'kissing scenes' montage at the film's end. Winning the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film in 1989, the film is often credited with reviving Italy's film industry, which later produced Mediterraneo and Life Is Beautiful. Film critic Roger Ebert gave it three stars and a half out of four[12] and four stars out of four for the extended version, declaring "Still, I'm happy to have seen it--not as an alternate version, but as the ultimate exercise in viewing deleted scenes."[13]

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 90% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 67 reviews, with an average score of 8/10.[14] The film also holds a score of 80 based on 20 reviews on Metacritic.[15] The film was ranked #27 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[16] The famed "kissing scene" montage at the end of the film was used in an episode of "Stealing First Base", an episode of The Simpsons that aired during on March 21, 2010, during its twenty-first season. The scene used Morricone's "Love Theme" and included animated clips of famous movie kisses, including scenes used in Cinema Paradiso as well as contemporary films not shown in the original film.

Awards

- 1989: Cannes Film Festival

- Grand Prix du Jury (tied with Trop belle pour toi)

- 1989: Golden Globe Awards

- 1989: Academy Awards

- 1991: BAFTA Awards

- 2010: 20/20 Awards

- Nominated – Best Picture

- Won – Best Foreign Language Picture

- Won – Best Cinematography

See also

- List of submissions to the 62nd Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Italian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

Notes

- ↑ Vancheri, Barabara (March 26, 1990). "Foreign-movie nominees discuss money, muses". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 10. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Cinema Paradiso (1990) - Box Office Mojo".

- ↑ "The 62nd Academy Awards (1990) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ Porter, Darwin; Danforth Prince (2009). Frommer's Sicily. Frommer's. p. 132. ISBN 0-470-39899-X.

- ↑ "Cinema Paradiso film locations (1988)". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations.

- ↑ Marcus, p. 99

- ↑ Bondanella, p. 454

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Cinema Paradiso". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ↑ "Umbrella Entertainment - Special Edition DVD". Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Umbrella Entertainment - Academy Award DVD". Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Umbrella Entertainment - Blu-ray". Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (March 16, 1990), "Cinema Paradiso Movie Review & Film Summary (1990)", rogerebert.com, retrieved August 8, 2015

- ↑ Roger Ebert (June 28, 2002), "Cinema Paradiso: The New Version Movie Review (2002)", rogerebert.com, retrieved August 8, 2015

- ↑ "Cinema Paradiso Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ↑ "Cinema Paradiso Movie Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More". Metacritic. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ↑ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema – 27. Cinema Paradiso". Empire.

- ↑ Awards IMDB

References

- Bondanella, Peter E. (2001). Italian cinema: from neorealism to the present. Continuum International Publishing. ISBN 0-8264-1247-5.

- Marcus, Millicent Joy (2002). After Fellini: national cinema in the postmodern age. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-6847-5.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cinema Paradiso |

- Official website

- Cinema Paradiso at the Internet Movie Database

- Cinema Paradiso at Rotten Tomatoes

- Cinema Paradiso at AllMovie