Coffee percolator

A coffee percolator is a type of pot used for complex brewing of coffee by continually cycling the boiling or nearly boiling brew through the grounds using gravity until the required strength is reached.[1]

Coffee percolators once enjoyed great popularity but were supplanted in the early 1970s by automatic drip coffee makers. Percolators often expose the grounds to higher temperatures than other brewing methods, and may recirculate already brewed coffee through the beans. As a result, coffee brewed with a percolator is susceptible to over-extraction. Percolation may remove some of the volatile compounds in the beans, resulting in a pleasant aroma during brewing, but a less flavoursome cup. However, percolator enthusiasts praise the percolator's hotter, more 'robust' coffee, and maintain that the potential pitfalls of this brewing method can be eliminated by careful control of the brewing process.

Brewing process

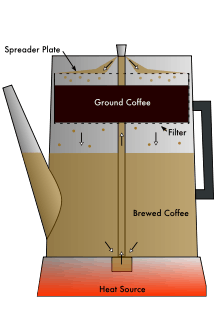

A coffee percolator consists of a pot with a small chamber at the bottom which is placed closest to the heat source. A vertical tube leads from this chamber to the top of the percolator. Just below the upper end of this tube is a perforated chamber.

The desired quantity of water is poured into the water chamber of the pot and the desired amount of a fairly coarse-ground coffee is placed in the top chamber. It is important that the water level be below the bottom of the coffee chamber.

The heat source under the percolator (such as a range or stove) heats the water in the bottom chamber. Water at the very bottom of the chamber gets hot first and starts to boil. The boiling makes bubbles rise up and push water up the vertical tube then out the top of the vertical tube. From the top of the tube, the water flows out and over the lid of the coffee chamber. Perforations in the lid distribute the water over the top of the coffee grounds. The water then seeps through the coffee grounds then through the bottom of the coffee chamber. From the bottom of the coffee chamber, the water drops onto the colder water at the top of the bottom chamber, helping to force water up the tube. This whole cycle repeats continuously.

As the brew continually seeps through the grounds, the overall temperature of the liquid approaches boiling point, at which stage the "perking" action (the characteristic spurting sound the pot makes) stops, and the coffee is ready for drinking. In a manual percolator it is important to remove or reduce the heat at this point (keeping in mind the adage "Coffee boiled is coffee spoiled"). Brewed coffee left on high heat for too long will acquire a bitter taste.

Some coffee percolators have an integral electric heating element and are not used on a stove. Most of these automatically reduce the heat at the end of the brewing phase, keeping the coffee at drinking temperature but not boiling.

Inventor

The percolating coffee pot was invented by the American-born British physicist[2] and soldier Count Rumford, otherwise known as Sir Benjamin Thompson (1753–1814). He invented a percolating coffee pot between 1810 and 1814 following his pioneering work with the Bavarian Army, where he improved the soldiers' diet as well as their clothing. It was his abhorrence of alcohol and his dislike for tea that led him to promote the use of coffee for its stimulating benefits. For his efforts, in 1791, he was named a Count of the Holy Roman Empire, and granted the formal title of Reichsgraf von Rumford. His pot did not use the rising of boiling water through a tube to form a continuous cycle.

The first modern percolator incorporating these features and capable of being heated on a kitchen stove was invented a few years later, in 1819, by the Parisian tinsmith Laurens. Its principle was then often copied and modified. There were also attempts to produce closed systems, in other words "pressure cookers".

The first US patent for a coffee percolator, which however still used a downflow method without rising steam and water, was issued to James Nason of Franklin, Massachusetts, in 1865.

Finally, an Illinois farmer named Hanson Goodrich patented the modern U.S. stove-top percolator as it is known today, and he was granted patent 408707 on August 16, 1889. It has the key elements, the broad base for boiling, the upflow central tube and a perforated basket hanging on it. He still describes the downflow as being the "percolating." Goodrich's design could transform any standard coffee pot of the day into a stove-top percolator. Subsequent patents have added very little.

Usage

Percolators are popular among campers and outdoorspeople because of their ability to make coffee without electricity. Non-pressure percolators may also be used with paper filters. Large 1970s-era percolators are still used in the 2000s at community events, church gatherings and other large group activities where a lot of coffee is needed.

Improvements

The method for making coffee in a percolator had changed very little since the introduction of the electric percolator in the early part of the 20th century. However, in 1970 commercially available "ground coffee filter rings” were introduced to the market. The coffee filter rings were designed for use in percolators, and each ring contained a pre-measured amount of coffee grounds that were sealed in a self-contained paper filter. The sealed rings resembled the shape of a doughnut, and the small hole in the middle of the ring enabled the coffee filter ring to be placed in the metal percolator basket around the protruding convection (percolator) tube.

Prior to the introduction of pre-measured self-contained ground coffee filter rings, fresh coffee grounds were measured out in scoopsful and placed into the metal percolator basket. This process enabled small amounts of coffee grounds to leak into the fresh coffee. Additionally, the process left wet grounds in the percolator basket. The benefit of the pre-packed coffee filter rings was two-fold: First, because the amount of coffee contained in the rings was pre-measured, it negated the need to measure each scoop and then place it in the metal percolator basket. Second, the filter paper was strong enough to hold all the coffee grounds within the sealed paper. After use, the coffee filter ring could be easily removed from the basket and discarded. This relieved the consumer from the task of cleaning out the remaining wet coffee grounds from the percolator basket.

Decline

With the introduction of the electric drip coffee maker in the early 1970s, the popularity of percolators plummeted, and so did the market for the self-contained ground coffee filters. In 1976, General Foods discontinued the manufacture of Max Pax, and by the end of the decade, even generic ground coffee filter rings were no longer available on U.S. supermarket shelves.

Terminology

The name is derived from the word "percolate" which means to cause (a solvent) to pass through a permeable substance especially for extracting a soluble constituent.[3] In the case of coffee-brewing the solvent is water, the permeable substance is the coffee grounds, and the soluble constituents are the chemical compounds that give coffee its color, taste, aroma, and stimulating properties.

A distinction must be made between the chemical process of percolation and the coffee percolator as a device. In 1880, Hanson Goodrich invented the coffee percolator.[4] His percolator was one of the earliest coffee brewing devices to use percolation rather than infusion or decoction as its mode of extraction, and he named it accordingly. Other brewing methods based on percolation followed, and this early naming convention can cause confusion with other percolation methods.

In 1813, Benjamin Thomson, Count Rumford published his essay, "Of the Excellent Qualities of Coffee", in which he disclosed several designs for percolation methods which would now be most closely related to drip brewing.[5]

Siphon brewers appeared in the early 1830s.[6] Using a combination of infusion and percolation, they were the first development in coffee percolation. However, the complex, fragile devices remained a curiosity. Siphon brewing relies on vapor pressure to raise water from a pressure chamber up to the brewing chamber where the coffee is infused. Once the heat source has been removed from the pressure chamber, the atmosphere within cools, lowering the pressure and drawing the coffee through a filter and back into the pressure chamber. Distinctions from percolator brewing include the fact that the water is not boiled in order to reach the grounds, that the majority of the extraction takes place during the infusion phase, and that the water is not recycled through the grounds.

Filter drip brewing (invented 1908, Melitta Bentz[7]) uses a bed of coffee grounds placed in a holder with a filter to prevent passage of the grounds into the filtrate and hot water is passed through the grounds by gravity. This is distinct from percolator brewing due to the fact that the water is not recycled through the grounds, and the water does not have to be boiled to reach the brew chamber. (In many automatic drip machines, the water is boiled or nearly boiled to raise it through a tube to the brewing chamber, but this is an implementation detail specific to those machines, and not required by the process, which was first used manually.)

Moka brewing (invented 1933, Alfonso Bialetti[8]) uses a bed of coffee grounds placed in a filter basket between a pressure chamber and receptacle. Vapor pressure above the water heated in the pressure chamber forces the water through the grounds, past the filter, and into the receptacle. The amount of vapor pressure that builds up, and the temperature reached, are dependent on the grind and packing ("tamping") of the grounds. This is distinct from percolator brewing in that pressure, rather than gravity, moves the water through the grounds; that the water is not recycled through the grounds; and that the water does not have to be boiled to reach the brew chamber. In the South of Europe, in countries like Italy or Spain, the domestic use of the moka expanded quickly and completely substituted the percolator by the end of the 1930s.

Since both percolator and drip brewing were available and popular in the North American market throughout the 20th century, there is little confusion in the United States and Canada between these methods. However, moka pots have only recently become readily available in that market; and vendors and customers alike often group moka pots with percolators, despite the fact that the two types of devices use different brewing mechanics.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coffee percolators. |

References

- ↑ "About Coffee: Coffee percolator". Ara Azzurro. 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ↑ "Sir Benjamin Thompson, count von Rumford". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. September 30, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ↑ "percolate". Merriam Webster. 2008. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ↑ "Inventor Goodrich Was in Our Town". Times-Leader, McLeansboro, Illinois. 1968. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ↑ The Complete Works of Count Rumford, Volume 5. American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 1812. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ↑ "The Historical Development of the Vacuum Coffee Pot". 2001. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ↑ "About Melitta Bentz". Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ↑ "The Origins of Bialetti". Bialetti Industrie S.p.A. Retrieved May 29, 2013.