Color model

A color model is an abstract mathematical model describing the way colors can be represented as tuples of numbers, typically as three or four values or color components. When this model is associated with a precise description of how the components are to be interpreted (viewing conditions, etc.), the resulting set of colors is called color space. This section describes ways in which human color vision can be modeled.

Tristimulus color space

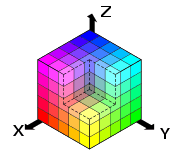

One can picture this space as a region in three-dimensional Euclidean space if one identifies the x, y, and z axes with the stimuli for the long-wavelength (L), medium-wavelength (M), and short-wavelength (S) light receptors. The origin, (S,M,L) = (0,0,0), corresponds to black. White has no definite position in this diagram; rather it is defined according to the color temperature or white balance as desired or as available from ambient lighting. The human color space is a horse-shoe-shaped cone such as shown here (see also CIE chromaticity diagram below), extending from the origin to, in principle, infinity. In practice, the human color receptors will be saturated or even be damaged at extremely high light intensities, but such behavior is not part of the CIE color space and neither is the changing color perception at low light levels (see: Kruithof curve).

The most saturated colors are located at the outer rim of the region, with brighter colors farther removed from the origin. As far as the responses of the receptors in the eye are concerned, there is no such thing as "brown" or "gray" light. The latter color names refer to orange and white light respectively, with an intensity that is lower than the light from surrounding areas. One can observe this by watching the screen of an overhead projector during a meeting: one sees black lettering on a white background, even though the "black" has in fact not become darker than the white screen on which it is projected before the projector was turned on. The "black" areas have not actually become darker but appear "black" relative to the higher intensity "white" projected onto the screen around it. See also color constancy.

The human tristimulus space has the property that additive mixing of colors corresponds to the adding of vectors in this space. This makes it easy to, for example, describe the possible colors (gamut) that can be constructed from the red, green, and blue primaries in a computer display.

CIE XYZ color space

- Main article: CIE 1931 color space

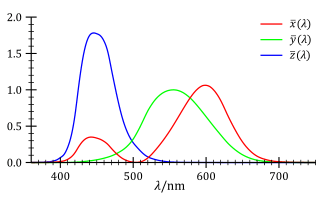

One of the first mathematically defined color spaces is the CIE XYZ color space (also known as CIE 1931 color space), created by the International Commission on Illumination in 1931. These data were measured for human observers and a 2-degree field of view. In 1964, supplemental data for a 10-degree field of view were published.

Note that the tabulated sensitivity curves have a certain amount of arbitrariness in them. The shapes of the individual X, Y and Z sensitivity curves can be measured with a reasonable accuracy. However, the overall luminosity function (which in fact is a weighted sum of these three curves) is subjective, since it involves asking a test person whether two light sources have the same brightness, even if they are in completely different colors. Along the same lines, the relative magnitudes of the X, Y, and Z curves are arbitrary. One could as well define a valid color space with an X sensitivity curve that has twice the amplitude. This new color space would have a different shape. The sensitivity curves in the CIE 1931 and 1964 xyz color space are scaled to have equal areas under the curves.

Sometimes XYZ colors are represented by the luminance, Y, and chromaticity coordinates x and y, defined by:

- and

Mathematically, x and y are projective coordinates and the colors of the chromaticity diagram occupy a region of the real projective plane. Because the CIE sensitivity curves have equal areas under the curves, light with a flat energy spectrum corresponds to the point (x,y) = (0.333,0.333).

The values for X, Y, and Z are obtained by integrating the product of the spectrum of a light beam and the published color-matching functions.

RGB color model

Media that transmit light (such as television) use additive color mixing with primary colors of red, green, and blue, each of which stimulates one of the three types of the eye's color receptors with as little stimulation as possible of the other two. This is called "RGB" color space. Mixtures of light of these primary colors cover a large part of the human color space and thus produce a large part of human color experiences. This is why color television sets or color computer monitors need only produce mixtures of red, green and blue light. See Additive color.

Other primary colors could in principle be used, but with red, green and blue the largest portion of the human color space can be captured. Unfortunately there is no exact consensus as to what loci in the chromaticity diagram the red, green, and blue colors should have, so the same RGB values can give rise to slightly different colors on different screens.

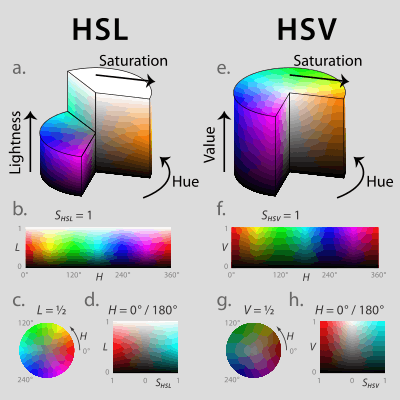

HSV and HSL representations

Recognizing that the geometry of the RGB model is poorly aligned with the color-making attributes recognized by human vision, computer graphics researchers developed two alternate representations of RGB, HSV and HSL (hue, saturation, value and hue, saturation, lightness), in the late 1970s. HSV and HSL improve on the color cube representation of RGB by arranging colors of each hue in a radial slice, around a central axis of neutral colors which ranges from black at the bottom to white at the top. The fully saturated colors of each hue then lie in a circle, a color wheel.

HSV models itself on paint mixture, with its saturation and value dimensions resembling mixtures of a brightly colored paint with, respectively, white and black. HSL tries to resemble more perceptual color models such as NCS or Munsell. It places the fully saturated colors in a circle of lightness ½, so that lightness 1 always implies white, and lightness 0 always implies black.

HSV and HSL are both widely used in computer graphics, particularly as color pickers in image editing software. The mathematical transformation from RGB to HSV or HSL could be computed in real time, even on computers of the 1970s, and there is an easy-to-understand mapping between colors in either of these spaces and their manifestation on a physical RGB device.

CMYK color model

It is possible to achieve a large range of colors seen by humans by combining cyan, magenta, and yellow transparent dyes/inks on a white substrate. These are the subtractive primary colors. Often a fourth ink, black, is added to improve reproduction of some dark colors. This is called "CMY" or "CMYK" color space.

The cyan ink absorbs red light but transmits green and blue, the magenta ink absorbs green light but transmits red and blue, and the yellow ink absorbs blue light but transmits red and green. The white substrate reflects the transmitted light back to the viewer. Because in practice the CMY inks suitable for printing also reflect a little bit of color, making a deep and neutral black impossible, the K (black ink) component, usually printed last, is needed to compensate for their deficiencies. Use of a separate black ink is also economically driven when a lot of black content is expected, e.g. in text media, to reduce simultaneous use of the three colored inks. The dyes used in traditional color photographic prints and slides are much more perfectly transparent, so a K component is normally not needed or used in those media.

Color systems

There are various types of color systems that classify color and analyse their effects. The American Munsell color system devised by Albert H. Munsell is a famous classification that organises various colors into a color solid based on hue, saturation and value. Other important color systems include the Swedish Natural Color System (NCS), the Optical Society of America's Uniform Color Space (OSA-UCS), and the Hungarian Coloroid system developed by Antal Nemcsics from the Budapest University of Technology and Economics. Of those, the NCS is based on the opponent-process color model, while the Munsell, the OSA-UCS and the Coloroid attempt to model color uniformity. The American Pantone and the German RAL commercial color-matching systems differ from the previous ones in that their color spaces are not based on an underlying color model.

Other uses of "color model"

Models of mechanism of color vision

We also use "color model" to indicate a model or mechanism of color vision for explaining how color signals are processed from visual cones to ganglion cells. For simplicity, we call these models color mechanism models. The classical color mechanism models are Young–Helmholtz's trichromatic model and Hering's opponent-process model. Though these two theories were initially thought to be at odds, it later came to be understood that the mechanisms responsible for color opponency receive signals from the three types of cones and process them at a more complex level.[1]

Vertebrate evolution of color vision

Vertebrate animals were primitively tetrachromatic. They possessed four types of cones—long, mid, short wavelength cones, and ultraviolet sensitive cones. Today, fish, reptiles and birds are all tetrachromatic. Placental mammals lost both the mid and short wavelength cones. Thus, most mammals do not have complex color vision—they are dichromatic but they are sensitive to ultraviolet light, though they cannot see its colors. Human trichromatic color vision is a recent evolutionary novelty that first evolved in the common ancestor of the Old World Primates. Our trichromatic color vision evolved by duplication of the long wavelength sensitive opsin, found on the X chromosome. One of these copies evolved to be sensitive to green light and constitutes our mid wavelength opsin. At the same time, our short wavelength opsin evolved from the ultraviolet opsin of our vertebrate and mammalian ancestors.

Human red-green color blindness occurs because the two copies of the red and green opsin genes remain in close proximity on the X chromosome. Because of frequent recombination during meiosis, these gene pairs can get easily rearranged, creating versions of the genes that do not have distinct spectral sensitivities.

See also

References

- ↑ Kandel ER, Schwartz JH and Jessell TM, 2000. Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York. pp. 577–80.